Chapter 2: Developing a Research Study

Module 5: Language Matters

Words have power! This module explores the importance of using clear, inclusive, and accessible language in digital research. This is especially important for online survey research, as it relates to the language of the survey, of recruitment, and dissemination.

Learning Objectives

- Use inclusive and empowering language in your research and writing

- Determine how best to reach culturally and linguistically diverse participants through different means of translation and accommodation

Case Study

Jasmine, a trans-woman with a physical disability, has joined a study aimed towards understanding how people with disabilities interact with public services. In the survey, Jasmine noticed that on multiple occasions, the term “special needs” was used to refer to those with disabilities. Feeling frustrated and stigmatized, she withdrew from the study, feeling the survey did not understand disability at all.

“… a need isn’t ‘special’ if it’s something everyone else takes for granted.”

(Carter-Long, 2017)

🧐 Consider This!

Have you ever reflected on your use of language? Do you believe that your way of communicating is inclusive?

Using Inclusive Language

Words have power! The language we use has the power to uplift, discourage or worse, exclude some readers. Inclusive language is one of the central pillars of EDIA policies; luckily, achieving this is very simple! First, let’s identify what inclusive language is.

Inclusive language is language that is geared towards acknowledging the power imbalances within our society and their detrimental effects. Focusing on diversity among people, inclusive language creates a safe space where all identities can thrive, fostering equity, inclusion and respect.

The Language of Disability

is a widely accepted language style that emphasizes the person before the disability. The key is to reference the disability after the person or group so as not to dissolve the human to just their disability. For instance, “woman with intellectual disabilities” ” or “person with dyslexia”.

However, some communities prefer , which emphasizes disability as part of an individual’s core identity. For example, “autistic person” or “visually impaired person”.

That being said, it is best practice to collaborate with those within the disability community to find the most appropriate terms to use (see: Co-Design).

Moreover, labels, stereotypes and condescending euphemisms are offensive and should not be used in any context. Many terms are highly integrated in everyday language. Consider how often accessible parking spaces are considered “handicapped spots”; how one might describe people with acquired disabilities as having “suffered from” disability; or those who use communication devices as “non-verbal”.

Disability is a natural variation of human diversity and should not be sensationalized or considered a supernatural phenomenon. Doing so actually leads to the assumption that it is an achievement or unusual for someone with a disability to live a successful, productive life.

For example, using terms such as “brave,” or “survivor,” are patronizing, inappropriate and offensive. Furthermore, condescending euphemisms are also problematic, because they come from the idea that disability is taboo. Some euphemisms can include terms such as “people of all abilities,” “people of determination,” and “differently abled” which are often used as a way to avoid speaking about people with disabilities.

Stigmatizing Versus Empowering Terminology

We know that how we describe disability is important to avoid stigmatizing and discriminating against people with disabilities. It’s also tough to navigate this language, especially when so much of it is heavily integrated into everyday speech. Below, you can find a useful table to guide your writing, adapted from recommendations provided by the United Nations for using disability inclusive language.

Module Activity 1

| Race & Ethnicity | Housing Status | Gender | Socioeconomic Status | Substance Use |

| Disability | Age | Sexual Orientation | Migration Status | Geography |

What language might be considered empowering for each of these groups? What might be considered stigmatizing?

Read the linked blogs and articles for some helpful terminology and case examples, but even more importantly, be sure that you ask the community.

Designing for Cultural and Linguistic Diversity

Inclusive research understands that participants will come from different cultural backgrounds, all of which deserve to be respected equally. These varying cultural and linguistic backgrounds will have differences in interpretation and, thus, in responses. Using culturally neutral wording may help prevent misunderstandings or biased responses. Avoid idioms, region-specific phrases, or assumptions about shared experiences, as these may not translate well across cultures.

| For example, using a phrase like, “It was raining cats and dogs”, when read without a Western, English-speaking lens, doesn’t make any sense! | The intended imagery is much simpler! |

|

|

To avoid discrepancies like this, you might opt to use phrases such as: “It was raining a lot,” or “it was raining for a long time”. This will ensure that the intended meaning is not lost to your audience. Often, people who are native speakers of a language will be unaware of the confusion caused by colloquialisms and turns of phrase. Therefore, it is important to pilot your survey with a diverse group of individuals, especially working with individuals from your target audience, to design your survey and survey materials.

Translations and Accommodations

In order to capture diverse populations in your survey data, consider the following:

- What primary language(s) are spoken by your target population? These may differ from the national language(s) of your region.

- What capacity do you have for language translation? Consider finances, time, and personnel that would be able to provide translation services.

- What language accommodations does your target population need?

Cultural Support for Language

Something else to consider, is that the national language(s) of your country and province are not native to every participant.

In Canada, for example, while the national languages are French and English, millions of Canadians come from diverse linguistic backgrounds, and will better understand the research, and communicate their experiences in their native languages.

Research the regions where your survey will be made available, and try to incorporate the major language groups of those regions.

🧐 Consider this!

Your survey will be available in multiple languages… But does your survey platform support multiple languages? If not, what strategies might you employ to make translations available?

Finding Language Translation

Often, student researchers do not have funding to conduct research in multiple languages. If you are in this position, there are a few options to consider:

Institutional support.

Your institution may have translation services for research, which may be available for free or reduced rates. Check with your school or research institution to see if this is provided to you as a researcher.

Professional translation.

This will be paid support of a qualified professional. If you lack funding, this will not be an option.

Grants or scholarships based around knowledge translation.

There are some available funding resources available from external sources that may support translation services for research. These are competitive, and will require time for applications and decisions. As such, they should be considered before beginning your research.

Non-professional translation:

Requesting support from volunteers or team members who are fluent speakers may be an option for you, but is not without risks. Volunteers are not professionally trained translators. This will make final translated documents subject to bias, inaccuracies and mistranslations.If your study materials are full of inaccuracy, any data you collect will also be subject to inaccuracy and may be unusable. Please ensure that you have native or fluent speakers of the language review all materials that use non-professional translations.

Machine translation:

This is not recommended, especially due to the many intrinsic biases in, and frequent mistakes produced by machine-generated, translations. As such, if you must use machine translations, please ensure that you have native or fluent speakers of the language review all materials which use AI translation.

Simple-text English translation:

All research benefits from the inclusion of simplified, basic English translations of materials. In the case that you are unable to translate all materials, having a simple English version of your study materials will ensure that at least some people who may not be fluent English-speakers will be able to participate. Simple English translations will also benefit research with people with intellectual or learning disabilities.

AI Corner!

Can I use AI to translate my writing or my survey? 🤖

AI as a tool for translation brings up several important questions about maintaining EDIA practices throughout your research. Take a look at this article for some more information about AI translations

Disability Support for Language

Language accommodations are not only cultural; they also include strategies to support people with disabilities who may communicate in different ways. While designing your survey research, think about the types of language accommodations that any participants with disabilities may need to be able to best comprehend and communicate. We have already talked about simple-text translations, but here are some more options to consider:

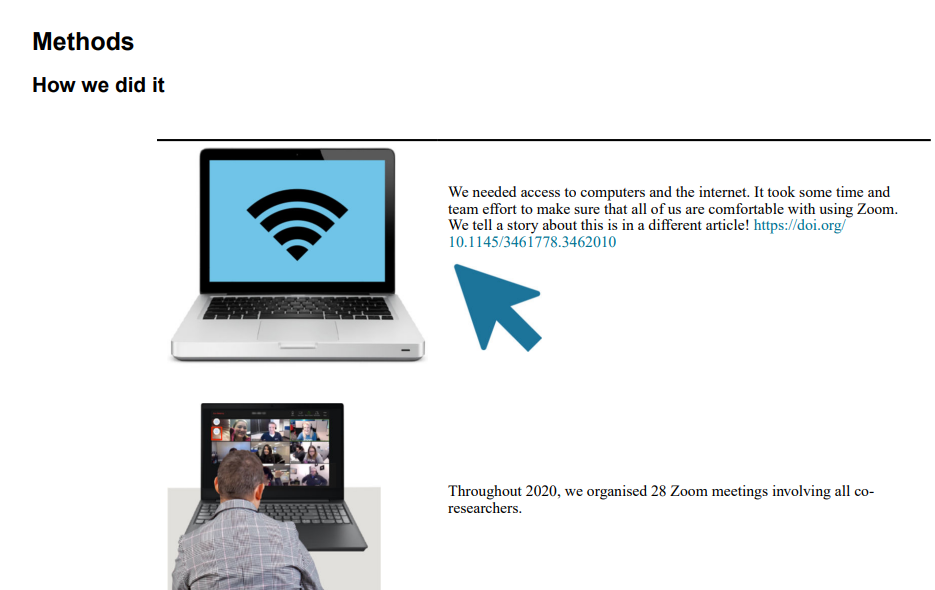

Pictograms or pictographs can be useful for communicating for those who may have difficulty with comprehending written language, for people of all ages. They may be used to clarify unknown words or terms, and enhance understanding of different concepts. Here is an example of the use of pictograms for improving accessibility of a research article, published in the British Journal of Learning Disabilities, by Cook et al. (2021):

Sign languages are also important forms of communication which can support participants who most comfortably understand signed language, as opposed to spoken or written language. The use of sign language videos to support survey participation is not new! Below is a video survey on accessible information, spoken in British Sign Language:

While we hope to make the language of our research as accessible and inclusive as possible, there are always ways to improve and gaps to fill. We have covered some elements of language, but there is more to learn. The best people to learn from are your the communities and stakeholders who are impacted by your research.

A language style that emphasizes the person before the disability. For example, "a person with autism" as opposed to "an autistic person".

A language style which emphasizes disability as part of an individual's core identity. For example, "autistic person" or "visually impaired person".

Artificial Intelligence, also called AI, is technology that helps computers and machines to complete complex tasks that are usually done by humans.

Feedback/Errata