Chapter 15 – Neurological system assessment

Reflex Testing

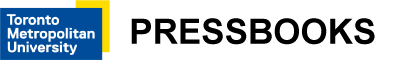

Reflexes are automatic and involuntary responses to stimuli. They serve a protective function and help maintain balance and coordinate muscle activity. Testing reflexes is an important way to localize a neurological lesion to determine the spinal level. Impaired reflex activity is noted as one of the earliest signs of neurological disruption when there is a problem (Campbell & Barohn, 2020). An example of a reflex action is immediate withdrawal of a hand after touching a hot object (such as a cup).

The neural pathway responsible for these responses is called the reflex arc: the stimulus initiates an impulse along the afferent neurons to the spinal cord and transmits the impulse to efferent neurons back to the limb’s muscles causing a reflex (here, contracting the muscle and pulling the hand away from the hot object). See Figure 22.

Figure 22: Reflex arc.

(Credit: Laura Guerin, Source: CK-12 Foundation

License: CC BY-NC 3.0, https://flexbooks.ck12.org/cbook/ck-12-middle-school-life-science-2.0/section/11.51/primary/lesson/touch-ms-ls/)

The human body has many reflexes, including autonomic (affecting inner organs) and somatic (affecting muscles). Reflexes are tested differently for a newborn/infant versus an adult/older child, and this section generally focuses on somatic reflex testing related to adults/older children, specifically deep tendon reflexes. Testing these reflexes involves percussing (tapping) a tendon with a reflex hammer, causing a quick stretch of the muscle and then the reflex contraction – this is why some call these stretch reflexes as opposed to deep tendon reflexes.

Many types of reflex hammers are available including the Taylor reflex hammer and the Queen Square hammer (see Figure 23). The Taylor reflex hammer is one of the most common because it is small and easy to carry around. However, many healthcare providers prefer the Queen Square hammer because it has a heavy end with a long flexible handle.

When trying to elicit a reflex, the target muscle must be relaxed. You can ensure this by positioning the limb so that the muscle is in a more relaxed state, and ask the client to relax the muscle. If this does not work, try what is called reinforcement: this technique involves eliciting an of a limb/area that is distant from the muscle you are testing. For example, when assessing upper limbs, you can ask the client to cross their legs and tighten their leg muscles; when assessing lower limbs, ask them to flex their arm, tighten their arm muscles, and clench their fist. Additionally, some ask the client to close their eyes tightly and clench their jaw.

The client may be positioned in various ways, often sitting on the exam table with their legs hanging over the edge. Expose the area you are assessing; tap the tendon on bare skin with sufficient force at least twice, and sometimes 3–5 times to elicit a reproducible reflex response. When striking a tendon with the reflex hammer, use a quick tap – on and off the area – while your wrist is loose and flexible.

Many scales have been developed to rate reflexes, so you should check with your unit/institution. Table 5 presents one commonly used scale that can be useful when rating and qualitatively describing the reflex. You should note whether reflexes are symmetrical and also the presence of any clonus, which is a rhythmic and oscillating contraction of the muscle associated with brisk responses and upper motor neuron diseases (see Video 24).

Video 24: Clonus.

Figure 23: Taylor reflex hammer (left) and Queen Square hammer (right).

Figure 23: Taylor reflex hammer (left) and Queen Square hammer (right).

Table 5: Deep tendon reflex scale. (Pociask, n.d.).

| Rating | Description |

| 0+ | No response or absent reflex |

| 1+ | Trace or decreased response |

| 2+ | Normal response |

| 3+ | Exaggerated or brisk response |

| 4+ | Sustained response (or very brisk response) |

The most commonly tested deep tendon reflexes are described and demonstrated in Video 25. After reviewing the steps in evaluating the deep tendon reflexes below, watch this video to observe how testing is done.

Video 25: Deep tendon reflexes.

Brachioradialis tendon reflex (testing integrity primarily C6, but can include C5 and C7 of the spinal cord):

- Ask the client to rest their forearm/wrists on their upper legs with the ulnar side resting on the legs.

- Tap the tendon about 5 cm superior to the wrist (radial styloid process); some testers tap at about 5–10 cm, but do not tap beyond 10 cm.

- The tap should elicit contraction of the brachioradialis muscle causing slight forearm supination and elbow flexion.

- Repeat on the other arm.

Bicep tendon reflex (testing integrity primarily C6, but can include C5 of the spinal cord):

- Ask the client to rest their forearm/wrists on their upper legs with the ulnar side resting on the legs and palms of hands facing slightly upwards.

- Place the thumb pad or index finger pad of your non-dominant hand over the bicep tendon with your hand wrapped around the arm/elbow. You should be able to feel the tendon, but do not apply too much pressure.

- Tap your thumb nail.

- The tap should elicit contraction of the bicep muscle causing elbow flexion and sometimes supination. Your focus should be on feeling, and possibly seeing, bicep muscle contraction.

- Repeat on the other arm.

Tricep tendon reflex (testing integrity primarily C7, but can include C6 and C8 of the spinal cord):

- Ask the client to hang their arms at their side and place your non-dominant hand on one of the upper arms just above the antecubital fossa. Then, gently lift their arm out to the side while the client bends their elbow at 90 degrees and allows you to hold the weight of their arm. It may be helpful to tell the client to fully relax their arm and lean on your hand like a railing or table.

- Tap 1–2 cm superior to the elbow.

- The tap should elicit contraction of the tricep muscle causing slight elbow extension. Your focus should be on feeling, and possibly seeing, tricep muscle contraction.

- Repeat on the other arm.

Patellar tendon reflex (testing integrity primarily L4, but can include L2 and L3 of the spinal cord):

- Ask the client to sit on the exam table with their legs hanging over the edge.

- Although not shown in the video, it is best practice to gently place your non-dominant hand over the quadricep muscle just superior to the patella.

- Tap inferior to the patella.

- The tap should elicit quadricep muscle to contract and also cause moderate knee extension. Your focus should be on feeling the quadricep muscle contraction.

- Repeat on the other leg.

Achilles tendon reflex (testing integrity primarily S1, but can include S2 and L5 of the spinal cord):

- Ask the client to sit on the exam table with their legs hanging over the edge.

- Although not shown in the video, you should assist the client to abduct the hip by lifting the upper leg away from the other leg.

- On the abducted leg, place your hand under the ball/toes of the foot and apply slight pressure to dorsiflex the foot.

- Tap the Achilles tendon at the back of the foot superior to the heel at the level of the ankle malleolus.

- The tap should elicit the calf muscle to contract and also cause plantar flexion (slight to moderate).

- Repeat on the other leg.

Normal findings might be documented as: “2+ reflexes bilaterally noted with brachioradialis, bicep, tricep, patellar, and Achilles deep tendon reflexes.”

Abnormal findings might be documented as: “1+ reflex with reinforcement noted with right patellar reflex.”

Knowledge Bites

The plantar reflex (Babinski reflex) is a superficial reflex via the skin (as opposed to deep tendon reflexes). It provides information about the possible presence of an upper motor neuron disease in the brain or spinal cord associated with conditions and diseases such as presence of a tumour, cerebral hemorrhage, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or multiple sclerosis. See Video 26 on how to test the plantar reflex (Babinski reflex), and follow these steps to evaluate the plantar reflex:

- Ask the client to lie in a supine position with legs/knees extended straight and shoes and socks off.

- Use a blunt instrument that is not too sharp, e.g., the end point of a reflex hammer, a cotton tip applicator, the end of a key, or your own thumbnail.

- Let the client know that the test might feel slightly uncomfortable.

- Hold the client’s foot under the ankle and then stroke the plantar side of the foot with the instrument from the medial to the lateral side of the heel up the lateral side of the foot and across the arch of the foot from lateral to medial. This can be uncomfortable, so only apply as much force as necessary. Typically, you will need to apply a moderate amount of force to elicit a response.

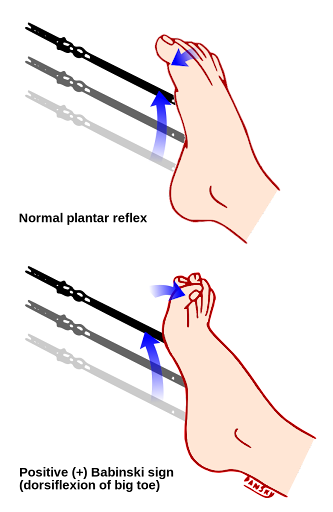

In adults, a normal response is toe flexion that is more pronounced in the smaller toes than the big toe; an abnormal response (sometimes called a positive Babinski) is toe extension that is more pronounced in the big toe, sometimes accompanied by separation of the toes (often called fanning), particularly the smaller toes (see Figure 24). Remember that a positive Babinski is normal in children younger than two years.

Video 26: How to test the Babinski reflex.

Figure 24: Babinski reflex.

(This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lawrence_1960_20.4-en.svg)

Contextualizing Inclusivity

Reflexes must be tested on bare skin, so it is important to recall the principles of a trauma-informed approach. Be aware that not all people will feel comfortable exposing their arms and legs due to cultural and/or other reasons. Thus, it is important to support the client and offer alternatives that work for them such as ensuring privacy, using a drape, having a family or friend present, and for some having the nurse be of the same gender.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurological disorder that affects the motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord (Oh & Kim, 2017). When performing deep tendon reflexes on a client with ALS, the reaction is hyperreflexia (Lewis, 2023). In addition, the Babinski reflex is elicited, which indicates the disease is in the upper motor neurons. Hyperreflexia and Babinski reflex are also symptoms of other conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS) or cocaine toxicity (Ali et al., 2019; Lewis, 2023; Mader et al., 2019; National Multiple Sclerosis Society, n.d).

Black clients with ALS are negatively affected by some healthcare professionals’ lack of knowledge. Some professionals mistakenly believe that Black people are not affected by diseases such as ALS, but these beliefs are not based on research and instead stem from racial biases (Carter, 2020; Casey, 2023). Additionally, some professionals have misdiagnosed ALS symptoms in Black clients as substance use or HIV (Carter, 2020). As a result of racial bias, Black clients may be misdiagnosed and/or experience delays in referral such that many clients are past the point of effective treatment (Carter, 2020). From an anti-oppressive and anti-racist perspective, nurses must acknowledge racial biases and inequities associated with ALS and the potential for discriminatory care. Nurses can also advocate for health resources for Black clients to receive accessible support care needs that are more person-centred (Oh & Kim, 2017).

Priorities of Care

A complication that can occur later in pregnancy is pre-eclampsia: this condition is characterized by high blood pressure and can lead to eclampsia (seizures). Affected clients may be ordered an anticonvulsant medication called magnesium sulfate to help prevent eclampsia convulsions (Shennan et al., 2021). A client who is administered magnesium sulfate must be monitored closely because there is a risk of toxicity causing neurological effects, such as the loss of deep tendon reflexes (Shennan et al., 2021). Deep tendon reflex testing can be used as a tool to determine the effects of the medication and whether the client is experiencing toxicity.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

References

Ali, O., Bueno, M. G., Duong-Pham, T., Gunawardhana, N., Tran, D. H., Chow, R. D., & Verceles, A. C. (2019). Cocaine as a rare cause of locked-in syndrome: A case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports, 13(1), 337–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2278-2

Carter, C. (2020). The ‘truth’ about ALS: Reconciling bias, motives, and etiological gaps. https://somatosphere.com/2020/als-bias-motives-etiological-gaps.html/

Casey, C. (2023). Study: Implicit Bias, Late Diagnosis Create Critical ALS Healthcare Gap.

Lewis, S. M. (2023). Lewis’s medical-surgical nursing in Canada: Assessment and management of clinical problems (J. Tyerman & S. L. Cobbett, Eds.; Fifth edition.). Elsevier.

Mader, E. C., Ramos, A. B., Cruz, R. A., & Branch, L. A. (2019). Full Recovery From Cocaine-Induced Toxic Leukoencephalopathy: Emphasizing the Role of Neuroinflammation and Brain Edema. JIM – High Impact Case Reports, 7, 2324709619868266–2324709619868266. https://doi.org/10.1177/2324709619868266

National Multiple Sclerosis Society (n.d.). Symptoms and Diagnosis. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis

Oh, J., & Kim, J. A. (2017). Supportive care needs of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease and their caregivers: A scoping review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), 4129–4152. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13945

Pociask, F. (n.d.). Deep tendon reflex examination and evaluation study guide. http://healthcaresciencesocw.wayne.edu/dtr/story.html

Shennan, A., Suff, N., Jacobsson, B., Simpson, J. L., Norman, J., Grobman, W. A., Bianchi, A., Mujanja, S., Valencia, C. M., & Mol, B. W. (2021). FIGO good practice recommendations on magnesium sulfate administration for preterm fetal neuroprotection. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 155(1), 31–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13856

is a muscle contraction without movement such as tightening the muscle.