Chapter 5: The Writing Process 4: Editing

Learning Objectives

1. Identify and correct sentence errors such as comma splices, run-ons, and fragments.

2. Identify and correct grammatical errors such as subject-verb and pronoun-antecedent disagreement, as well as faulty parallelism.

3. Identify and correct syntax errors such as misplaced modifiers.

4. Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

-

- Apply proper use of sentence structure, grammar, and punctuation.

- Use a systematic approach to edit, revise, and proofread.

- Edit and proofread documents to eliminate errors.

- Revise documents to improve clarity, correctness, and coherence.

Grammar organizes the relationships between words in a sentence, especially between the doer and action, so that the reader can understand in detail who’s doing what. When you botch those connections with grammar errors, however, you risk confusing the reader. Severe errors force the reader to interpret what you meant. If the reader then acts on an interpretation different from the meaning you intended, major consequences can ensue, including expensive damage control. You can avoid being a liability and embarrassing yourself by following some simple rules for how to structure your sentences grammatically. By following these rules habitually, especially when you apply them at the proofreading stage, not only will your writing be clearer to the reader and better organized, but your thought process may become more organized as well.

5.2.1: Sentence Errors

Readers who find comma splices, fragments, and run-on sentences lose confidence in the writer’s command of language and thus the quality of their work. Such giveaways suggest that the writer doesn’t know much about sentence structure and punctuation. This is especially bad coming from native English speakers in their 20s or older because it says that they still don’t understand the basics of their own written language even after decades of using it. It’s important to know what to look for, then, when proofreading your draft for sentence errors.

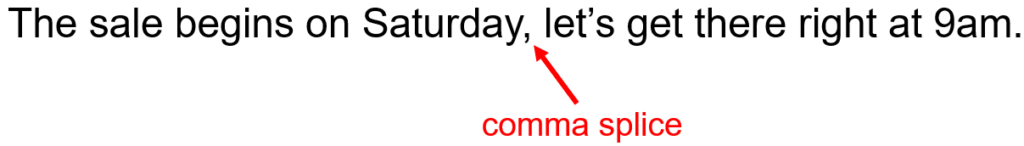

1. Comma Splices

A comma splice is simply two independent clauses separated by only a comma. Perhaps the error comes from writers thinking that, because the two clauses say closely related things, they need something a little “lighter” than a period to separate them. While separating them with a comma is certainly possible, doing so with a comma alone shows that the writer doesn’t fully understand what a sentence is and what commas do.

Figure 5.2.1.1: A comma splice is a comma separating two independent clauses

Spotting a comma splice requires being able to identify an independent clause—i.e. the combination of a subject and predicate (noun + verb) that can stand on its own as a sentence (see §4.3.1 and §4.3.2 above). In the Figure 5.2.1.1 example above, the first independent clause’s subject is “The sale” and its predicate is “begins on Saturday” (sale + begins), so it can stand on its own as a sentence if it ended with a period. The second is an imperative clause (see Table 4.3.1 for more on imperatives) with the main verb being “let,” so it too can stand on its own as a sentence. When proofreading, be on the lookout for commas that have independent clauses on either side—that is, clauses that can stand on their own as sentences.

Fixing a comma splice is as easy as swapping out the comma for the correct punctuation or adding a conjunction, depending on the relationship you want to express between the two clauses. Altogether, you have four options in correcting a comma splice—two that replace the comma with other punctuation and two that leave it as-is but add a conjunction:

- Replace the comma with a period to turn the two independent clauses into two sentences if each is a distinct enough complete thought. Don’t forget to capitalize the letter that followed the comma. Correcting the comma splice in the Figure 5.2.1.1 example would look as follows:

The sale begins on Saturday. Let’s get there at 9am.

- Replace the comma with a semicolon to form a compound sentence if the two independent clauses are related enough to be in the same sentence:

The sale begins on Saturday; let’s get there at 9am.

If the writer wanted something a little lighter than a period to separate the two clauses, then a semicolon fits the bill.

- Add a coordinating conjunction (e.g., and, but, so; see Table 4.3.2a for all seven of them) to form a compound sentence if it clarifies the relationship between the independent clauses:

The sale begins on Saturday, so let’s get there at 9am.

Note that if you see three or more independent clauses with commas between them and an and or or before the last one, then it’s a perfectly correct (albeit probably too long) compound sentence that combines whole clauses rather than just nouns or verbs. See the final example given in Comma Rule 4 below for a sentence organized into a list of clauses.

- Add a subordinating conjunction (e.g., when, if, though, etc.; see Table 4.3.2a for more) to form a complex sentence (see Table 4.3.2b for more on complex sentences):

When the sale begins on Saturday, let’s get there at 9am.

Though each of the above comma-splice fixes is grammatically correct, the last two are best because adding a conjunction clarifies the relationship between the ideas expressed in the two clauses.

A common comma splice error involves “however” following a comma that separates two independent clauses. Consider the following sentence that are grammatically equivalent:

The company raised its rates, however, we were granted an exemption.

= The company raised its rates, however we were granted an exemption.

= The company raised its rates, we were granted an exemption.

Seeing that you have independent clauses on either side of the comma preceding “however” is easier if you imagine the sentence without both “however” and the comma following it, as in the third example sentence above. Fixing the error is as easy as replacing the comma preceding “however” with a semicolon and ensuring that a comma follows “however,” which is a conjunctive adverb (see Comma Rule 2 below):

The company raised its rates; however, we were granted an exemption.

This is somewhat tricky because “however” can be surrounded by commas if it’s used as an interjection between the subject and predicate (see Comma Rule 3 below) or between clauses in a complex sentence:

This particular company, however, had been delaying raising its rates for years.

With the company raising its rates, however, we had to apply for an exemption.

Because you see the first clause beginning with “With” in the second example, you know that it’s a dependent clause that will end with a comma followed by the main clause. It’s thus possible to add “however” where the comma separates the subordinate from the main clause.

When proofreading, be on the lookout for “however” surrounded by commas. If the clauses on either side can stand on their own as sentences, fix the comma splice easily by replacing the first comma with a semicolon. If one of the clauses before or after is a subordinate clause and the other a main clause, however, then you’re safe (as in this sentence). For more on comma splices, see the following resources:

- Run-On Sentences and Comma Splices and the Repairing Run-On Sentences exercises (Darling, 2014a)

- Comma Splices (Wells & Brizee, 2009)

- Fixing Comma Splices (Plotnick, 2003)

2. Run-on Sentences

Whereas a comma splice places the wrong punctuation between independent clauses, a run-on (a.k.a. fused) sentence simply omits punctuation between them. Perhaps this comes from the second clause following the first so closely in the writer’s free-flowing stream of consciousness that they don’t think any punctuation is necessary between them. While it may be clear to the writer where one idea-clause ends and the other begins, that division isn’t so clear to the reader. The absence of punctuation will cause them to trip up, and they’re forced to mentally insert the proper punctuation to make sense of it, which is frustrating.

Spotting a run-on is easy if it’s just commas missing before coordinating conjunctions. If you string together the last couple of sentences concluding the above paragraph, for instance, and use conjunctions to separate the four clauses without accompanying commas, you’ll get a cumbersome run-on:

That division isn’t so clear to the reader and the absence of punctuation will cause them to trip up and they’re forced to mentally insert the proper punctuation to make sense of it and that’s frustrating.

“Run-on” is a good description for sentences like this because they seem like they can just go on forever like a toddler tacking on clause after clause using coordinating conjunctions (… and … and … and …). Though the above sentence would be perfectly correct if commas preceded “and” and “so,” adding further clauses would just exhaust the reader’s patience, commas or no commas. A run-on is not necessarily the same as a long sentence, then, as you can see with the perfectly correct 239-word sentence in Algonquin College’s Guide to Grammar and Writing page on run-ons (Darling, 2014). Such a long sentence can become convoluted, however, especially for audiences who may struggle with English such as ESL learners.

Sometimes spotting a run-on is just a matter of tripping over its nonsense. Say you’re reading your draft and then come across the following sentence:

We’ll have to drive the station is too far away to get there on foot.

You’re doing just fine reading this sentence up until the word “is” since, the way things were going, you probably expected a vehicle to follow the article “the.” Assuming “drive” is being used as a transitive verb (Simmons, 2007) that takes an object, “station wagon” would make sense. When you see “is” instead of “wagon,” however, you might go back and see if the writer forgot to put “to” before “station” to make “drive to the station.” That doesn’t make sense either, however, given what follows. Finally, you realize that you’re really dealing with two distinct independent clauses starting with a short one, and that some punctuation is missing after “drive.” The sentence is like a chain with a broken link.

Once you’ve found that missing link, fixing a run-on is just a simple matter of adding the correct punctuation and perhaps a conjunction, depending on the relationship between the clauses. Indeed, the options for fixing a run-on are identical to those for fixing a comma splice. Following the same menu of options as those presented above, you would be correct doing any of the following:

- Add a period between the clauses (after “drive”) and capitalize “the” to form two sentences:

We’ll have to drive. The station is too far away to get there on foot.

- Add a semicolon between the clauses to form a compound sentence:

We’ll have to drive; the station is too far away to get there on foot.

This is the easiest, quickest fix of them all.

- Add a comma and coordinating conjunction to form a compound sentence:

We’ll have to drive, for the station is too far away to get there on foot.

- Add a subordinating conjunction to form a complex sentence:

We’ll have to drive because the station is too far away to get there on foot.

Again, though each of the above run-on fixes is grammatically correct, only the last one best clarifies the relationship between the ideas expressed in the two clauses. For more on run-on sentences, see the following resources:

- Run-On Sentences and Comma Splices (Darling, 2014a)

- Fragments and Run-Ons (Wells & Brizee, 2013)

- Grammar: Run-On Sentences and Sentence Fragments (Walden University, 2016)

3. Sentence Fragments

A sentence fragment is one that’s incomplete usually because either the main-clause subject, predicate, or both are missing. The most common sentence fragment is the latter, where a subordinate clause poses as a sentence on its own, usually with its main clause being the preceding or following sentence. If the final example in §5.2.1.2 above were a fragment, it would look like the following:

We’ll have to drive. Because the station is too far away to get there on foot.

Recall from §4.3.2 that a complex sentence combines a main (a.k.a. independent) clause with a subordinate (a.k.a. dependent) clause, and the cue for the latter is that it begins with a subordinating conjunction (see Table 4.3.2a for several examples). In the above case, the coordinating conjunction “because” makes the clause subordinate, which must join with a main clause in the same sentence to be complete.

The fix is simply to join the fragment subordinate clause with its main clause nearby so that they’re in the same sentence. You can do this in one of two ways, either of which is perfectly correct:

- Delete the period between the sentences and make the subordinating conjunction lowercase if the subordinate clause follows the main clause:

We’ll have to drive because the station is too far away to get there on foot.

- Move the subordinate clause so that it precedes the main clause, separate the two with a comma, and make the first letter of the main clause lowercase:

Because the station is too far away to get there on foot, we’ll have to drive.

The same applies to sentences that begin with any of the seven coordinating conjunctions. These are technically fragments but can be easily fixed either by joining them with the previous sentence to make a compound. You could also change the conjunction to something else such as a conjunctive adverb like “However” for “but” or “Also” for “and” followed by a comma:

| The station is too far away to get there on foot. But we’ll drive. | The station is too far away to get there on foot, but we’ll drive. | The station is too far away to get there on foot. However, we’ll drive. |

You may also encounter fragments that are just noun phrases, verb phrases, prepositional phrases, and so on. Of course, we speak often in fragments rather than full sentences, so if we’re writing informally, such fragments are perfectly acceptable. Even in some formal documents, such as résumés, fragments are expected in certain locations such as the Objective statement (an infinitive phrase) and profile paragraph (noun phrases) in the Qualifications Summary (see §8.2 below).

If we’re writing formally, however, these fragmentary phrases are variations on the error of leaving sentences incomplete. The easy fix is always to re-unite them with a proper sentence or to make them into one by adding parts.

| We thank you for choosing our company. As well as the impressive initiative you’ve taken. | We thank you for choosing our company and are impressed by the initiative you’ve taken. We thank you for choosing our company. You’ve shown impressive initiative. |

The beauty of the English language is that there’s and endless number of ways to say something and still be grammatically correct as long as you know what makes a proper sentence. If you don’t, reviewing §4.3.1 and §4.3.2 above till you can spot the main subject noun and verb in any sentence, as well as tell if they’re missing. For more on fragments, see the following resources:

- Sentence Fragments (Darling, 2014b)

- Fragments and Run-Ons (Wells & Brizee, 2013)

- Grammar: Run-On Sentences and Sentence Fragments (Walden University, 2016)

For exercises in spotting and fixing comma splices, run-ons, and fragments, see the digital activities at the bottom of the Guide to Grammar and Writing pages linked above (Darling, 2014a & 2014b), as well as Exercise: Run-ons, Comma Splices, and Fused Sentences (Purdue OWL, 2009).

5.2.2: Grammar Errors

Let’s focus on some of the most common grammar errors in college and professional writing:

- 5.2.2.1: Subject-verb disagreement

- 5.2.2.2: Pronoun-antecedent disagreement

- 5.2.2.3: Faulty parallelism

- 5.2.2.4: Dangling and Misplaced Modifiers

1. Subject-verb Disagreement

Perhaps the most common grammatical error is subject-verb disagreement, which is when you pair a singular subject noun with a plural verb (usually ending without an s) instead of a singular one (usually ending with an s), or vice versa. Spotting such disagreements of number requires being able to identify the subject noun and main verb of every sentence and hence knowledge of sentence structure (see §4.3.1 and §4.3.2 above). The search for the main subject noun and verb is complicated by the fact that many other nouns and verbs in various phrase types can crowd into a sentence. The following subject-verb agreement (abbreviated “Subj-v Agr.”) rules help you know what to look for.

Quick Rules

Click on the rules below to see further explanations, examples, advice on what to look for when proofreading, and demonstrations of how to correct common subject-verb disagreement errors associated with each one.

Singular subjects take singular verbs.

The first of many cuts is going to be the deepest.

The indefinite pronouns each, either, neither, and those ending with -body or -one take a singular verb.

If each of you chooses wisely, someone is going to win the prize, but everybody wins because neither really loses.

Collective nouns and some irregular nouns with plural endings are singular and take a singular verb.

The band isn’t going on stage until the news about the stage lighting is more positive.

Plural noun, compound noun, and plural indefinite pronoun subjects take plural verbs.

The rights of the majority usually trump those of minority groups, except when money and politics conspire, and both usually do.

Compound subjects joined by or or nor take verbs that agree in number with the nouns closest to them.

Neither your lawyers nor the justice system is going to be able to adequately punish this type of crime.

The verb in clauses beginning with there or here agrees with the subject noun following the verb.

There are two types of people in the world, and here comes one of them now.

Extended Explanations

Subj-v Agr. Rule 1.1: Singular subjects take singular verbs.

When the subject of the sentence—the doer of the action—is a singular subject (i.e. one doer), the verb (the action it performs) is always singular. Watch out, though: this rule holds even if phrases modifying the subject or intervening parenthetical elements are plural. You just have to be able to tell that those phrases and parenthetical elements aren’t the main subject and therefore don’t count when determining the number of the verb.

Correct:

Our investment is paying off nicely.

Why it’s correct: The singular subject “investment” takes the singular verb “is,” which is the third-person singular form of the verb to be.

Correct:

The source of all our network errors disappears whenever you do a system restart.

Why it’s correct: The singular subject “source” takes the singular main verb “disappears”; the plural noun “errors” immediately before the verb is just the last word in a prepositional phrase (“of . . .”) modifying the subject.

Correct:

Stalling for time to think of better responses doesn’t work in a job interview.

Why it’s correct: The singular subject “stalling,” a gerund (action noun) takes the singular main verb “does”; the plural noun “responses” immediately before the verb is just the last word in a prepositional phrase (“of . . .”) embedded in an infinitive phrase (“to think . . .”) embedded in another prepositional phrase (“for . . .”).

Correct:

The singer-songwriter, along with new additions to her five-piece backup band, arrives at the press conference at 1:30pm.

Why it’s correct: Despite the parenthetical addition of other actors, the grammatical subject (“singer-songwriter”) is still singular and takes a singular verb.

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader connect the doer of the action with main action itself, especially when a variety of phrases, including nouns of different number, intervene between the subject noun and main verb.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for subject nouns (the main doers of the action) and the main verbs that the subject noun takes, then ensure that both are singular. Look out especially for verbs that are wrongly plural in form because the nouns immediately preceding them are plural despite the fact that they are only part of phrases modifying the main subject noun.

Incorrect:

The best vodka in the opinion of all the experts at international competitions are surprisingly the bottom-shelf Alberta Pure.

The fix:

The best vodka in the opinion of all the experts at international competitions is surprisingly the bottom-shelf Alberta Pure.

Incorrect:

The lucky winner, as well as three of their best friends, are going on an all-expenses-paid trip to beautiful Cornwall, Ontario!

The fix:

The lucky winner, as well as three of their best friends, is going on an all-expenses-paid trip to beautiful Cornwall, Ontario!

In the first incorrect example sentence above, the proximity of the plural nouns “experts” and “competitions” to the main verb (form of to be) probably made the writer think that the verb had to be plural, too. The true subject noun of the sentence, however, is “vodka,” which is singular and therefore takes the singular verb “is” no matter what comes between them. In the second incorrect sentence, the grammatical subject is the singular “winner,” so the main verb should be the singular “is,” not the plural “are.” A parenthetical interjection between the subject and the verb, even if it appears to pluralize the subject with “as well as,” “along with,” “plus,” or the like, technically doesn’t make a compound subject (see Subj-v Agr. Rule 2 below for more on compounds).

Subj-v Agr. Rule 1.2: The indefinite pronouns each, either, neither, and those ending with -body or -one take a singular verb.

When the subject noun of the sentence is the indefinite pronoun either, neither, each, anybody, everybody, nobody, somebody, anyone, everyone, someone, no one, or none (see Table 4.4.2a above on pronouns), it is singular and takes a singular verb.

Correct:

Each has enough personal finance know-how to handle her own taxes.

Why it’s correct: The subject pronoun “Each” can be thought of the singular “Each one” and therefore takes a singular verb In this case the verb is “has” rather than the plural “have” that would be appropriate if the subject were “All of them.”

Correct:

Either is fine.

Why it’s correct: The subject pronoun “Either” can be thought of the singular “Either one,” despite implying a pair of options, and therefore takes a singular verb—in this case “is.”

Correct:

“Perhaps none is more vulnerable than James, a soft-spoken 19-year-old who is quick to flash a smile that would melt ice” (Chianello, 2014, ¶24).

Why it’s correct: The subject pronoun “none” in this case can be thought of the singular “no one” because the topic of the sentence concerns a single person. The pronoun therefore takes a singular verb—in this case “is” rather than the plural “are.”

Exception: None can sometimes be a plural indefinite pronoun depending on what comes later in the sentence.

Correct:

“None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free” (Goethe, 1809, p. 397).

Why it’s correct: The subject pronoun “none” can be thought of as “no people,” consistent in number with the later pronoun “those,” and thus a plural pronoun that takes a plural verb—in this case “are,” not “is.”

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader see that the “one” or “body” suffix in each of these indefinite pronouns is singular, even if the word applies to many people, and therefore takes a singular verb form.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for any indefinite pronouns ending with -one or -body taking a plural main verb and change the verb to the singular form.

Incorrect:

Everybody here share our opinion on quantitative easing.

The fix: Everybody here shares our opinion on quantitative easing.

The fix: All here share our opinion on quantitative easing.

Incorrect:

Each of you send enough carbon into the atmosphere to poison a river.

The fix: Each of you sends enough carbon into the atmosphere to poison a river.

The fix: All of you send enough carbon into the atmosphere to poison a river.

Here, the “every” part of the word everybody in the first incorrect sentence and the fact that the second address a group suggest to the confused writer that a plurality of actors is at play, thus requiring the plural verbs “share” and “send.” Wrong! The “body” part of the word is the operative one; being singular, it takes a singular verb—“shares” in this case—and “Each” is short for “Each one.” Another fix in each case is to make the subject the plural “All” and keep the verbs plural.

Subj-v Agr. Rule 1.3: Collective nouns and some irregular nouns with plural endings are singular and take a singular verb.

Collective nouns such as “group” are grammatically singular and thus take a singular verb despite meaning several people or things. The following are common collective nouns:

| army audience band board bundle cabinet class committee company corporation council crew |

department faculty family firm gang group jury majority membership minority navy pack |

party plethora public office school senate society task force team tribe troupe |

The same is true of any company name that ends in s or has a compound name (e.g. Food Basics, Long & McQuade), as well as any compound of inanimate objects treated as a singular entity (e.g., meat and potatoes is considered one dish; see Subj-v Agr. Rule 2 below for more on compounds). Likewise, some special-case words that look like plurals because they end with s instead take singular pronouns and verbs, especially names for games and disciplines or areas of study, as well as dollar amounts, distances, and amounts of time:

| acoustics billiards cards civics crossroads darts # dollars |

dominoes economics ethics gymnastics # hours # metres linguistics |

mathematics measles mumps news physics rabies shambles |

Note that most of these words will be plural if used other than meaning disciplines, fields of study, games, or number of units. For instance, when you’re playing darts, you would use the plural verb in “Three darts remain” to refer to three individual darts in your hand but use a singular verb when saying “Darts is a way of life” because you’re now using “darts” in the sense of the game rather than the object.

Correct:

The committee demands action on the latest media blunder.

Why it’s correct: The collective noun “committee” is singular, despite being comprised of several people, and therefore takes the singular verb “demands,” not the plural “demand.”

Correct:

A demolition crew of three sledgehammer-wielding heavies is levelling the house as we speak.

Why it’s correct: The collective noun “crew” is singular despite being followed by a prepositional phrase detailing how many people are in the crew. Despite also the plural noun “heavies” preceding the main verb, the singular “is” is the correct verb rather than the plural “are.”

Correct:

Food Basics has a deal on for ice cream right now, and Dolce & Gabbana has some fresh new styles coming this season.

Why it’s correct: Though the subject nouns seem plural because one ends with s and the other compounds two names, being a single corporate entity in each case makes them singular and take the singular verb “has” rather than the plural “have.”

Correct:

Oh look, green eggs and ham is on the menu.

Why it’s correct: Though the subject noun seems plural because it is a compound of a plural and singular noun, it is considered one singular dish and therefore takes the singular verb “is” rather than the plural “are.”

Correct:

The news is so depressing today.

Why it’s correct: Though the subject noun seems plural because it ends with s, “news” is a singular noun taking the singular verb “is,” not the plural “are.”

Correct:

Ethics isn’t an optional field of study for business professionals.

Why it’s correct: Though the subject noun seems plural because it ends with s and the singular “ethic” is also a legitimate word, it acts in this case as a singular entity because it is a field of study and therefore takes the singular verb “is.”

Correct:

Five dollars donated to the right charities is all that’s needed to save a life.

Why it’s correct: Though the subject noun seems plural because it contains more than one dollar, it acts as a singular entity and thus takes the singular verb “is” regardless of the noun “charities” that comes before it in a prepositional phrase.

Correct:

Ten kilometres is too far to walk because those ten kilometres are going to make us late.

Why it’s correct: The first “Ten kilometers” is a grammatically singular subject because the distance as a whole is meant. The second instance refers to each individual kilometer together with the others, however, so it is grammatically plural, taking the plural pronoun “those” and verb “are.”

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader connect the singular grammatical subject performing a single action in concert as one entity with the main verb, especially when phrases of different number come between them.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for count nouns, as well as special-case nouns that look plural but are actually singular, such as games and areas of study, like those identified above. Ensure that the main verb following them is singular rather than plural.

Incorrect:

A pack of lies averaging around twenty per day are winning over a confused and angry swath of the electorate.

The fix: A pack of lies averaging around twenty per day is winning over a confused and angry swath of the electorate.

Incorrect:

The acoustics in here are so bad that it makes me want to study acoustics, which are all about how sounds behave in certain environments.

The fix: The acoustics in here are so bad that it makes me want to study acoustics, which is all about how sounds behave in certain environments.

In the first incorrect sentence above, the collective noun “pack” is grammatically singular and must therefore take the singular verb “is,” not the plural verb “are”), despite it being comprised of a plurality of things (“lies”) identified in the prepositional phrase following it. In the second incorrect sentence, we see two different types of the word “acoustics.” One type means “sound quality,” acts as a plural grammatical subject, and therefore takes the plural verb “are.” The other, meaning the study of how sounds interact with the environment, takes the singular verb “is,” not the plural verb “are.”

Subj-v Agr. Rule 2: Plural noun, compound noun, and plural indefinite pronoun subjects take plural verbs.

When the subject of the sentence is plural or contains two or more nouns or pronouns joined by and to make a compound subject, the verb describing the action they perform together is always plural regardless of whether the nouns are singular or plural. The verb is plural even if the compounded subject noun closest to the verb is singular. Other word types that take plural pronouns and verbs include:

- The indefinite pronouns both, few, many, several, and others

- Some items that seem singular because they are assembled into one unit, such as binoculars, glasses, jeans, pants, scissors, shears, and shorts

- Sport teams with singular names, such as the Colorado Avalanche and Tampa Bay Lightning

- Bands of musicians with singular-sounding names such as the Tragically Hip and Arcade Fire

Correct:

Self-driving cars are going to revolutionize more than just the auto industry.

Why it’s correct: The plural subject noun “cars” takes the plural main verb “are.”

Correct:

Goodness, we have our work cut out for us.

Why it’s correct: The plural subject pronoun “we” takes the plural main verb “have”

Correct:

All the network systems and the mainframe we’ve been updating are going to have to be liquidated now.

Why it’s correct: The compound subject with the plural noun “systems” and singular noun “mainframe” takes the plural main verb “are.” All the other verbs are part of embedded phrases that don’t affect the verb number.

Correct:

A few of them say they can’t go, but several are still going.

Why it’s correct: The plural indefinite pronouns “few” and “several” take the plural verbs “say” and “are” respectively.

Correct:

These pants don’t fit, these scissors don’t cut, and these shears are kaput.

Why it’s correct: Though each of these subject nouns sells as one item, they are considered pairs grammatically and therefore take plural verbs such as “don’t” instead of the singular “doesn’t.”

Correct:

The Tragically Hip are playing their final concert in Kingston where they played their first show 32 years earlier.

Why it’s correct: As a five-piece band of musicians, the Tragically Hip are a grammatically plural noun despite having a singular-sounding name, and therefore take the plural verb “are.”

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader connect the doer of the action with the main action itself, especially when a variety of phrases, including nouns of different numbers, intervene between the subject noun and main verb.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for subject nouns (the main doers of the action) and the main verbs that the subject noun takes, then ensure that both are plural. Look out especially for compound subjects with a singular noun close to the verb tricking you into making the main verb singular.

Incorrect:

Most major auto manufacturers and, of course, Tesla is leading the way towards self-driving cars via a switch to all-electric drivetrains.

The fix: Most major auto manufacturers and, of course, Tesla are leading the way towards self-driving cars via a switch to all-electric drivetrains.

Incorrect:

I can respect their musicianship, but Rush just annoys me, or maybe it’s just Geddy Lee’s voice.

The fix: I can respect their musicianship, but Rush just annoy me, or maybe it’s just Geddy Lee’s voice.

In the first incorrect example above, the proximity of the singular noun “Tesla” to the main verb probably made the confused writer think that the verb had to be the singular “is,” too. The subject is in fact a compound, however: “manufacturers and . . . Tesla.” Changing the main verb to a plural form easily fixes the subject-verb disagreement of number.

In the second incorrect example, the band Rush seems like it should be a singular noun and take the singular verb “annoys” because the word rush is singular; as a trio of musicians, however, the band is grammatically plural and takes the plural verb “annoy.” Notice, when we use the noun “band” in front of “Rush” so that “band” is grammatically the subject noun, however, we use a singular verb following Subj-v Agr. Rule 1.3 above.

Subj-v Agr. Rule 3: Compound subjects joined by or or nor take verbs that agree in number with the nouns closest to them.

When the subject of the sentence is a compound joined by the coordinating conjunction or or nor, the number (singular or plural) of the verb is determined by the subject noun that comes immediately before it.

Correct:

Either the players or the coach is going to take the fall for the loss.

Why it’s correct: Though this is a compound subject comprised of the plural “players” and singular “coach,” the main verb is the singular “is” because “or” joins the two subject nouns and the one closest to the verb, “coach,” is singular.

Correct:

When neither the project lead nor dozens of engineers dare to doubt the safety of the launch, you have all the makings of a Challenger-like disaster.

Why it’s correct: The plural subject pronoun “dozens,” as the second part of the compound subject including the singular “lead,” takes the plural main verb “dare” because it is closer.

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader see the two compounded subject nouns as separate actors performing the verb action independently of one another rather than together.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for plural verbs that disagree in number with singular subject nouns closest to them when the subject nouns are joined by or or nor.

Incorrect:

A rock or a hard place are your only choice in this situation.

The fix: A rock or a hard place is your only choice in this situation.

In the incorrect example above, the compounding of the two singular nouns likely made the confused writer think that the verb should be plural as it is when and compounds subject nouns. When or or nor compounds subject, however, the verb must agree with whatever subject noun comes immediately before it.

Subj-v Agr. Rule 4: The verb in clauses beginning with there or here agrees with the subject noun following the verb.

When a sentence or clause begins with the pronoun there or here, the subject noun follows the verb and therefore determines whether the verb should be singular or plural. In other words, what comes before the verb usually determines whether the verb is singular or plural, but in this case, what comes after the verb does that. In such expletive constructions, as they’re called, here or there are not actually subjects.

Correct:

There appears to be a mighty storm approaching on the horizon.

Why it’s correct: The singular subject noun “storm” following the verb takes the singular verb “appears.”

Correct:

Here is a pencil and here are some forms you need to fill out.

Why it’s correct: The singular subject noun “pencil” following the main verb takes the singular verb “is” in the first clause. The plural subject noun “forms” in the second clause takes the plural verb “are.”

Correct:

There happen to be six conditions on which the growth of our business depends.

Why it’s correct: The plural subject noun “conditions” following the verb takes the plural verb “happen” rather than the singular “happens.”

Correct:

There is nothing to the allegations of wrongdoing.

Why it’s correct: The singular subject noun “nothing” following the verb takes the singular verb “is” regardless of the plural noun “allegations” in the prepositional phrase modifying the subject noun.

Correct:

There are too many applications to sort through in the given timeframe.

Why it’s correct: The plural subject noun “applications” following the verb takes the plural verb “are.”

How This Helps the Reader

In sentences beginning with the pronoun there, following this rule cues the reader towards the number of the subject noun before it appears.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for sentences or clauses beginning with there and ensure that the verb agrees with the noun that follows it. The verb isn’t necessarily singular just because there comes before the verb (where the subject is usually located) and seems like a singular pronoun.

Incorrect:

I can’t believe there just happens to be two tickets to the show you wanted to see in my pocket here.

The fix: I can’t believe there just happen to be two tickets to the show you wanted to see in my pocket here.

Incorrect:

Here is a bar graph and pie chart you can extrapolate results from.

The fix: Here are a bar graph and pie chart you can extrapolate results from.

In the first incorrect sentence above, the pronoun “there” is not the subject noun of the relative clause following “that”; the plural noun “tickets” is the subject and therefore takes the plural verb “happen” rather than the singular “happens.” In the second incorrect sentence, the grammatical subject is the compound noun “bar graph and pie chart” following “Here,” so the main verb must be the plural “are,” not the singular “is.”

For more on subject-verb agreement and how to correct disagreement, see the following resources:

- Making Subjects and Verbs Agree (Paiz, Berry, & Brizee, 2018)

- Self Teaching Unit: Subject-Verb Agreement (Benner, 2000), including exercises

For more exercises, see Subject-Verb Agreement I and II (Darling, 2014c).

2. Pronoun Errors

For more on pronoun-antecedent disagreements of number (e.g., Everybody has an opinion on this, but they are all wrong), ambiguous pronouns (e.g., The plane crashed in the field, but somehow it ended up unscathed—was the plane or field left unscathed?), and pronoun case errors (e.g., Rob and me are going to the bank—would you say “me is going to the bank”?), see the following resources:

- Using Pronouns Clearly (Berry et al., 2013)

- Pronoun Case (Berry et al., 2010)

- Gendered Pronouns & Singular “They” (Berry et al., 2017)

For self-check exercises on correct use of pronouns, see Pronouns – Exercises (Darling, 2014d).

3. Faulty Parallelism

For more on parallelism, see the following resources:

- Parallel Structure (Driscoll, 2018a)

- Parallel Structure in Professional Writing (Driscoll, 2018b)

- Parallel Structure and Parallelism I exercise (Darling, 2014e)

4. Dangling and Misplaced Modifiers

For more on dangling modifiers, see the following resources:

- Dangling Modifiers and How to Correct Them (Berry & Stolley, 2013)

- The Dangling Modifier and The Misplaced Modifier (Simmons, 2011)

- Modifier Placement and the Modifier Placement I exercises (Darling, 2014f)

Key Takeaways

Writing sentences free of common grammar errors such as comma splices and subject-verb disagreement not only helps you avoid confusing the reader and embarrassing yourself, but also helps keep your own thinking organized.

Exercises

- Go through the above sections and follow the links to self-check exercises at the end of each section to confirm your mastery of the grammar rules.

- Take any writing assignment you’ve previously submitted for another course, ideally one that you did some time ago, perhaps even in high school. Scan for the sentence and grammar errors covered in this section now that you know what to look for. How often do such errors appear? Correct them following the suggestions given above.

References

Benner, M. L. (2000). Self teaching unit: Subject-verb agreement. Retrieved from https://webapps.towson.edu/ows/moduleSVAGR.htm

Berry, C. Brizee, A., Boyle, E. C. M., Atherton, R., Geib, E., Sheble, M., & Murton, H. (2010, April 17). Pronoun case. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/595/02/

Berry, C. Brizee, A., Boyle, E. C. M., Atherton, R., Geib, E., Sheble, M., & Murton, H. (2013, February 21). Using pronouns clearly. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/595/01/

Berry, C. Brizee, A., Boyle, E. C. M., Atherton, R., Geib, E., Sheble, M., & Murton, H. (2017, November 2). Gendered pronouns & singular “they.” Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/595/04/

Berry, C., & Stolley, K. (2013, January 7). Dangling modifiers and how to correct them. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/597/01/

Chianello, J. (2014, November 29). Giving youth futures. The Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved from http://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/giving-youth-futures

Darling, C. (2014a). Run-on sentences and comma splices and Repairing run-on sentences. Guide to Grammar and Writing. Retrieved from https://plato.algonquincollege.com/applications/guideToGrammar/?page_id=3374 and http://www.dactivity.com/activity/index.aspx?content=r3SA7E9Yf

Darling, C. (2014b). Sentence fragments. Guide to Grammar and Writing. Retrieved from https://plato.algonquincollege.com/applications/guideToGrammar/?page_id=596

Darling, C. (2014c). Subject-verb agreement I and II. Guide to Grammar and Writing. Retrieved from http://www.dactivity.com/activity/index.aspx?content=37AytmjXJ8 and http://www.dactivity.com/activity/index.aspx?content=18hS2l9Byj

Darling, C. (2014d). Pronouns – Exercises. Guide to Grammar and Writing. Retrieved from https://plato.algonquincollege.com/applications/guideToGrammar/?page_id=3423#ex

Darling, C. (2014e). Parallel structure and Parallelism I. Guide to Grammar and Writing. Retrieved from https://plato.algonquincollege.com/applications/guideToGrammar/?page_id=4213 and http://www.dactivity.com/activity/index.aspx?content=12jiBRskrR

Darling, C. (2014f). Modifier placement and Modifier placement I. Guide to Grammar and Writing. Retrieved from https://plato.algonquincollege.com/applications/guideToGrammar/?page_id=3380 and http://www.dactivity.com/activity/index.aspx?content=yKDDHtzkv

Driscoll, D. L. (2018a, March 28). Parallel structure. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/623/01/

Driscoll, D. L. (2018b, March 23). Parallel structure in professional writing. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/644/01/

Goethe, J. W. v. (1809, trans. 1982). Die wahlverwandtschaften, Hamburger ausgabe [Elective affinities, Hamburg edition]. Munich: DTV Verlag. Retrieved from https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Johann_Wolfgang_von_Goethe

Paiz, J. M., Berry, C., & Brizee, A. (2018, February 21). Making subjects and verbs agree. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/599/01/

Plotnick, J. (2003, August 13). Fixing comma splices. University of Toronto. Retrieved from http://www.uc.utoronto.ca/comma-splices

Purdue OWL. (2009, October 31). Exercise: Run-ons, comma splices, and fused sentences. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/exercises/5/26/5

Shankbone 33. (2011, September 28). Day 12 Occupy Wall Street September 28 2011 Shankbone 33. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16761555

Simmons, R. L. (2007, November 24). The transitive verb. Grammar Bytes! Retrieved from http://www.chompchomp.com/terms/transitiveverb.htm

Simmons, R. L. (2011, September 4). The dangling modifier and The misplaced modifier. Grammar Bytes! Retrieved from http://www.chompchomp.com/terms/danglingmodifier.htm and http://www.chompchomp.com/terms/misplacedmodifier.htm

Walden University. (2016, April 2). Grammar: Run-on sentences and sentence fragments. Writing Centre. Retrieved from https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/grammar/runonsentences

Wells, J. M., & Brizee, A. (2009, August 7). Comma splices. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/engagement/2/1/34/

Wells, J. M., & Brizee, A. (2013, March 22). Fragments and run-ons. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.english.purdue.edu/engagement/2/1/33/