Section 2: The ACT Model

Hexaflex: The ACT model of psychological flexibility

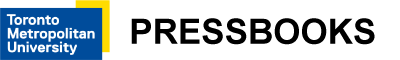

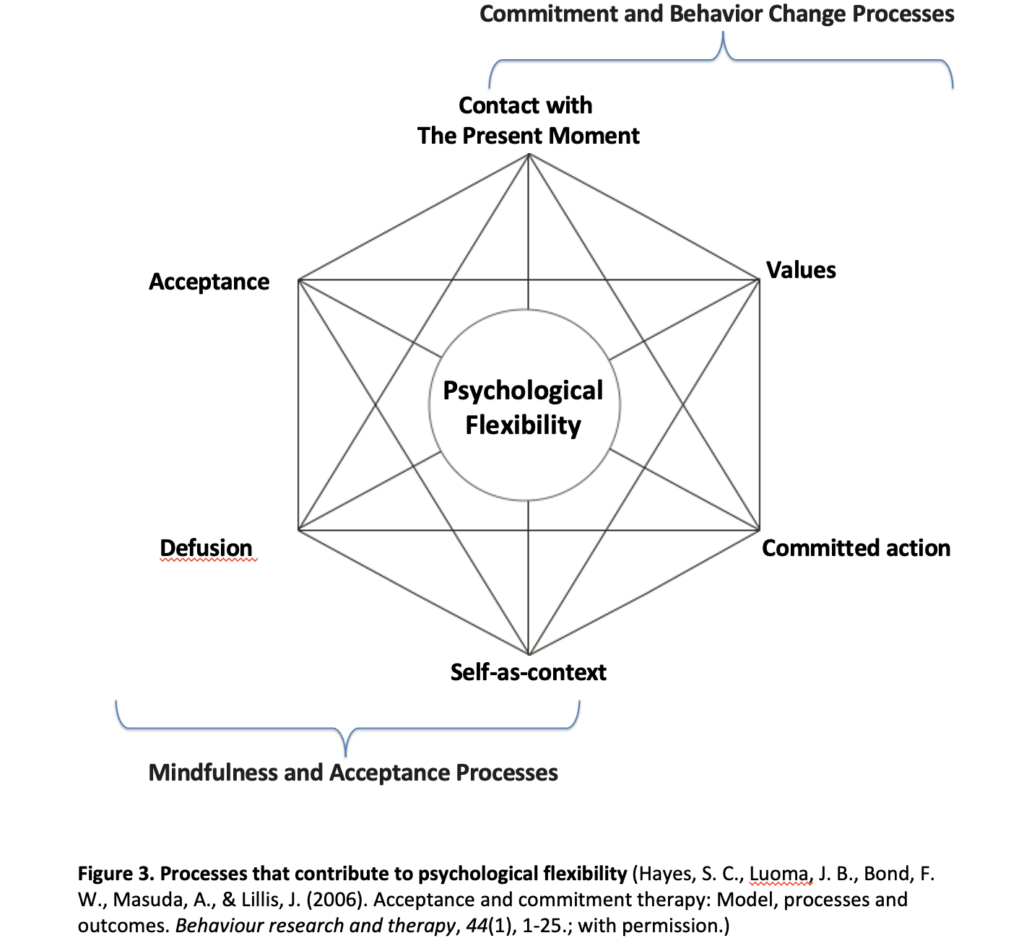

The ACT model of psychological inflexibility/flexibility consists of six pairs of psychological processes of challenges and interventions. The following table consists of highlights of these processes (Fletcher & Hayes, 2005; Hayes et al., 2013)

| Repertoire-narrowing processes that contribute to psychological inflexibility (See Figure 2; (Hayes et al, 2013) |

Repertoire-expanding processes that contribute to psychological flexibility (See Figure 3; Fletcher & Hayes, 2005) |

| Cognitive fusion occurs when we treat our thoughts literally as reality. Cognitive fusion helps us function and make sense of the world. We usually don’t question what our thoughts tell us. For example, “the sun is round”, “fire is hotter than ice”, and “hell is hotter than earth” all sound real and logical to you. As you read and think about them, they become transparent to you that they are just thoughts in your head. No matter how “true” or how “false” the thoughts are – they are actually all just thoughts. In some cases, cognitive fusion can be harmful. For example, one may become fused with evaluative judgments (e.g., “mental illness is shameful”) and treat it as if it is reality, allowing them to guide one’s actions – to stigmatize someone or to feel ashamed. | Defusion occurs when we “deliteralize” from our thoughts, that is, we recognize thoughts as just thoughts. Many cognitive defusion techniques have been proven to be effective; for example, watching thoughts like watching TV; word repeating; label the ongoing process of thinking – “I am having the thought that ‘I am useless’.” These defusion techniques foster our capacity to experience thoughts as thoughts, rather than just “knowing” (thinking) that “thoughts are just thoughts” or getting caught up in trying to evaluate the “truthfulness” of thoughts. |

| Experiential avoidance is the attempt to avoid unwanted thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations or memories even though the attempt is costly to one’s wellbeing, ineffective, or unnecessary. In many cases, experiential avoidance actually reinforces psychological struggles. For example, when a person worries about being judged and tries to avoid the unpleasant feelings through social withdrawal, her/his anxiety may worsen, his/her functioning may be limited, and overall suffering is increased. | Acceptance is “a moment by moment process of actively embracing the private events evoked in the moment without unnecessary attempts to change their frequency or form…” (p. 319). ACT exercises enable a person to increase his/her willingness to experience their psychological events (e.g., anxiety, shame, or craving) more fully as an alternative to avoidance or control strategies. |

| Dominance of the conceptualized past and feared future refers to a way of being, whereby we are stuck in our thoughts of the past and/or concerns about the future. Often times, when we have been hurt before in the past (e.g. bullied or abused) or we have done things we regretted, they continue to dominate and influence our present life. Similarly, worries about things that have not happened yet (e.g. ‘my mental illness will get worse in the future’, ‘I cannot cope’, and ‘I can never be a good partner’) may constrict our life. | Contact with the present moment refers to shifting our attention to what is happening here and now, including our thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations and external stimuli (sound, sight, smell, etc.). Training our ability to attend to the present moment can decrease the dominance of our thoughts about our past/future. It can also help us appreciate and enjoy what is currently before us in the present moment and respond more fully and effectively to the present situation and demands. |

| Attachment to the conceptualized self (or self-as-content) refers to our getting fixated on a fused identity based on evaluations, concepts, and stories we have about who we are. While concepts of ourselves can be helpful (e.g. knowing you are a mother helps you play that role), but being stuc” with it means you can feel like losing a sense of self when this fused role is lost (e.g. losing a son to suicide.) Being fused with our stories (e.g. “I’m always the odd, unloved, and unpopular person”) can also constrict how we lead our lives and what we choose to pursue. | Self-as-context refers to freeing oneself from a restrictive fused identity or conceptualized self, and connecting to one’s higher consciousness, or gaining a transcendent sense of self or pure awareness (p. 321). Instead of being fused with our psychological “contents” (i.e. our thoughts, feelings, emotions, roles, stories), we are able to be in touch with our selves as the “context” in which psychological events occur. This is also called the “observer self.” From your experience and perspective, “you” have always been “you” throughout your whole life, while all other things about you (that isn’t actually you) constantly change – e.g. thoughts, feelings, body, roles, stories, memories, etc. |

<Continued on next page>

| Lack of values clarity refers to not being in touch with our chosen values, or what really matters to us. Instead, our actions may be guided by our fusion and other unworkable rules and stories, and we feel stuck. We may also be busy avoiding things that provoke negative emotions like fear, anxiety, and sadness. (E.g. if others know I have a mental illness, no one will like me…. better not get help from others…) | Values refer to meaningful, chosen life directions that support us to disengage from cognitive processes that drive us to act based on social compliance, avoidance or fusion, and to take purposive action based on what matters to us. Values are different from goals in that they are not something one can attain, but rather, are ever-present directions that guide us. (E.g. embracing or learning new things as a value does not end with formal schooling; it also means that if one cannot continue with academic schooling due to mental illness, learning can still continue, such as learning to garden). |

| Inaction, impulsivity, or avoidant persistence refers to patterns of behaviors (e.g., reactive, socially withdrawn, etc.) that reinforce our psychological struggles and prevent us from engaging in mindful living. For example, we may not take actions towards our values (e.g. “there is injustice out there, but someone else will take care of it so I never speak out”); impulsively react to our emotions, thoughts, and stories (e.g. “my sick family member made me angry – so I yell at him/her and vow never to speak to him/her again”); or avoid unpleasant internal experiences and external situations (e.g. “I don’t really want to expose myself to situations that remind me I have judgments and stigmatizing thoughts”). | Committed action refers to engaging in patterns of behavior or action that are consistent with our chosen values. For example, if one of our chosen directions is to have self-compassion, then taking time each day for self-care and reflection is a committed action. Commitment requires acceptance and defusion of barriers that inevitably get in the way. Commitment is not about being perfect and never failing, but about the willingness of making a 100% commitment in the present moment. If one fails, one persists and gets back on track again. Committed action can be built from small steps to larger steps. Committed action is also about the process rather than the outcome. (e.g. the value in loving a mentally ill relative is expressed through the meaningful committed actions of caring for him/her, rather than the outcome and whether s/he will necessarily get better or become appreciative) |

| Mindfulness as integrated processes in ACT Mindfulness, in the context of ACT, refers to a set of related processes – acceptance, defusion, contact with the present moment, and a transcendent sense of self – that work in concert to support us in defining clear values and a chosen life direction and taking committed action that liberates us from suffering and allows us to move towards a meaningful life. |

|