Watch ECLD Module 2 – Bird-in-Hand Principle (15:58)

Planning-based thinking begins with the end in mind and assumes at least a somewhat predictable and stable future. Searching, in contrast, starts where you are, not where you think you might want to end up. You can’t control an unpredictable world. You can only understand the means at your disposal which dictate what is possible, what potential directions you might want to explore, and who might be able to help you on the adventure. It starts by being curious about yourself and your interests, values, beliefs, attitudes, skills and character. Both planning and searching require good goal-setting and time management skills to set priorities, fit everything in, and enhance your productivity and overall happiness.

Entrepreneurial Principle #1: Bird-in-the-Hand

Unlike managers who can control vast amounts of resources and capital to achieve their goals, entrepreneurs start with few resources, but an understanding of themselves. Most start with nothing but their own character, human capital and social capital. This is certainly true when trying to spot opportunities to discover an interesting potential future career.

There are three primary aspects of the Bird-in-the-Hand Principle: your Character, Human Capital and Social Capital. (I note that personal Financial Capital is also important, especially when considering life design questions around viable careers, goals or retirement.)

Your Character involves understanding who you are, your personality, interests, values and beliefs. Certain basic traits or personality types are “sticky” and difficult, if not impossible, to change such as whether you make decisions quickly or prefer to gather more detail and seek other opinions. It is important that you understand your basic preferences such as whether you are introverted or extraverted or like to work in teams or prefer working on your own. However, it is far more important to understand and judge your characteristics, beliefs and attitudes that are changeable. Do you make and keep commitments or do you frequently let people down? Are you a hard worker or do you give up easily? Are you curious, alert, engaged, proactive and motivated or does it take a lot to make you exert effort? Are you optimistic, hopeful, positive, conscientious and trustworthy? Do you have grit, tenacity and resiliency? All these attitudes, habits and values are under your control and thus changeable through life design. More importantly, as we’ll show in chapters 8-10, these aspects of your character have a far greater impact on your happiness and well-being than job, money, marriage, age or health!

Your Human Capital involves your productive capacity or sustainable competitive advantage over other people – your knowledge and skills that differentiate you. This can include your education and experience but also includes what you do outside of these formal roles. What life-long learning do you pursue like reading books, watching instructional videos or engaging in focused practice? What organizations or side-hustles do you work with so that you can practice and improve your skills (such as building websites, doing research and gaining customers)? Can you demonstrate what you can do? What values can you create for a potential employer? What are your signature strengths, interests and talents that you can build into something exceptional and unique?

Your Social Capital or Relationship Capital consists of how strong your relevant network is for supporting your career aspirations. I mentioned earlier the expression “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know” and the fact that less than 20% of all jobs are advertised and the other 80% are only available to those within the employer’s social network. These are the so-called insiders or friends-of-friends or referrals; people who can be, or introduce you to, a potential employer and ideally vouch for your character and human capital. In addition to those in your career-related network, your friends and social circle can support and enhance your career and life goals. “You’re the average of the five people you spend the most time with” is a common phrase attributed to Abraham Lincoln and Jim Rohn.

Potential employers, partners, team members or investors deeply care about your character and human capital and may not even consider you if your social capital does not overlap with theirs.

In “Trust, Ethics, Character and Competence in Angel Investing” I interviewed dozens of Angel investors about why they invest in certain entrepreneurs and not others and discovered that the entrepreneur’s trustworthiness, ethics, character, human and social capital was far more important than the startup idea, traction, customers or revenues. I describe how to assess these intangible assets in my book “A Practical Guide to Angel Investing: How to Achieve Good Investment Returns” published by the National Angel Capital Association (NACO).

Why would any employer pay you more than minimum wage or more than what someone else would be willing to work for on the other side of the planet in a low-wage country? What do you know how to do that others can’t do as well? Have you merely gone from one entry-level job to another over your lifetime or have you built up a portfolio of increasingly distinctive and rare capabilities to build a sustainable competitive advantage? How are you different from the other millions of graduates with a BComm degree? What can you become exceptional at?

I remember an ex-boss of mine once rejecting a potential new hire by stating that “He doesn’t have 20 years of experience; he only has one year of experience that he’s been doing for 20 years.” Building a career means that you are not only learning more and more each year within your current job, but also building your portfolio of capabilities, skills, interests and connections outside of your job.

Dr. Seligman, the founder of Positive Psychology and one of the world’s leading authorities on how to build and sustain long-term happiness and well-being, says that you should discover what your “signature strengths” are. In order to flourish in your career, be satisfied in your work and find happiness, the research shows that you are far better off focusing on building upon your strengths and interests rather than fixing your weaknesses. We’ll dig into that more in Tool #3, but let’s get started by seeing what your life looks like now.

Tool #1: Start Where You Are – The Wheel of Life

Watch and Use Tool #1 – Wheel of Life (15:25 or 25:40) The longer version of this tool includes an example of my Wheel of Life, my Draft Design Challenges, my Patterns and finally my Final Design Challenges. Recognizing that my challenges are very different from yours, I also created a shorter version of the video without these examples if you want to save time.

The purpose of this assignment is to help you check your pulse, identify what your design challenges might be in a variety of areas, and set goals for the remaining assignments in this course. You want to get started searching in the right direction and focus your time and attention on the right activities. You also want to make sure that your life has balance and that, over time, each of the major elements of your wheel gets the attention it needs in order to achieve overall long-term happiness. You can and should defer some elements while you focus on others, but over the long-term your wheel has to be in balance in order to spin properly. Goal-Setting Tool #9 will improve your time management skills and help set goals for the rest of the course.

In ENT 401 and 78AB, our focus is on your career-related design challenges. You can and should set and pursue a wide variety of design challenges in each area of your life, but the emphasis of this course and the majority of the assignments are related to your career.

Each person’s Wheel of Life will look different, so please don’t feel constrained to use only the one I show you in the video. As a minimum you should consider the three elements of the Bird-in-the-Hand Principle as well as a portfolio of career-related elements such as a job and all those things you do outside your job in order to position yourself more broadly in your chosen career (i.e. side-hustles, startup ventures, and/or social changemaking projects).

Here are a couple examples of student assignments using this tool – the 3rd one is particularly excellent and thorough. (Also watch on D2L the in-class feedback video on Week 2 Wheel of Life 15Sep2020. You can learn a lot from seeing the strengths and weaknesses of your fellow students’ assignments.)

I find that having more than 10 major elements in my life starts to become overwhelming and stress-inducing. So I deliberately group some things together. For example, I used to have a category for sailing, one for music, another for friends, another one for sports and another for health but have since decided to lump these all together. I also used to separate my various Toronto Met-related jobs (one for teaching, one for research, one for Enactus, one for TMEI, one for starting up the DMZ…) but I now combine these or categorize them differently. Enactus, for example, is now included as a social changemaking project that I do for my own reasons and not because it’s related to my job at TMU.

I find that having more than 10 major elements in my life starts to become overwhelming and stress-inducing. So I deliberately group some things together. For example, I used to have a category for sailing, one for music, another for friends, another one for sports and another for health but have since decided to lump these all together. I also used to separate my various Toronto Met-related jobs (one for teaching, one for research, one for Enactus, one for TMEI, one for starting up the DMZ…) but I now combine these or categorize them differently. Enactus, for example, is now included as a social changemaking project that I do for my own reasons and not because it’s related to my job at TMU.

Just make sure that your wheel captures all the major elements of your life that are important to you as a springboard for brainstorming what’s working and what’s not. What aspects of your life give rise to different design challenges that you want to focus time and attention on?

As described in the YouTube video ECLD Tool #1 – Wheel of Life, once you create your wheel, rate each element for level of satisfaction, need for change and activities or challenges that arise. Use Post-it notes to capture your brainstorming. You are seeking quantity over quality during this divergent thinking phase. Try to create at least 30 post-it notes using good visualization techniques. You need to be able to read them at a distance. In the longer version of the video, I go around my wheel and describe some of my personal activities, priorities and challenges that arise from each element.

This figure shows the general process we are following in this tool. Starting at the far left, you start by drawing a blank wheel with the major categories of your life. You then brainstorm activities, challenges and issues to fill up your wheel with post-it notes.

In the convergent thinking phase, you want to remove the post-its from the wheel and manipulate your post-it notes to look for patterns by clustering, separating, organizing and/or rearranging them (plot by level of importance, urgency, interest, satisfaction, need for change, etc.) in order to gain insights. I show you an example of how I organized my long-term priorities into a 2×2 matrix in the video.

Here’s a simple example of how one student prioritized his general design challenge categories into level of satisfaction (shown by the sad and happy faces) and need for change (at left shown by the delta) to no need for change (at right) before digging into the ones that most needed change and caused unhappiness (the side-hustle, social capital and social changemaking categories).

Here are a couple student examples of 2 x 2 matrices used in the convergent phase.

Finally, you want to capture your learnings into a set of design challenges to get you searching in the right directions. As shown in the longer video, one of my examples is “How Might I (HMI)… hire students to work on a relevant COVID-related Social Changemaking Project and put money into student pockets and the economy while also helping me with video editing and technology?” Another design challenge was “HMI… Reduce the number of my work-related projects while retaining all my international social network?”

How to Write a Good Design Challenge Question (DCQ)

A Good Design Challenge Question gives you a direction to search in. You don’t need to have a specific goal, but at least need a hypothesis to give you some direction or orientation. The DCQ should be HELPFUL. “How do a find a great career that I love”, for example, provides no direction. It could have been written by anyone and is not helpful to YOU. So you want to add any specificity that might help guide you. “How do I find a career in the field of law?” provides slightly more direction, as does “How do I figure out if I want to work in a large Bay Street law firm or a small boutique law firm where I can bring my dog to work?”

If you are just getting started on your search, your DCQs may be quite vague if you don’t know if you want to work in a place that is fast-paced or slow and stable, or whether you want to live in Toronto or someplace else, or work in a 9-5 job or someplace more entrepreneurial. Different individuals will have different levels of specificity. One person may know they want to be a lawyer or real estate agent or wealth manager, whereas another might have absolutely no clue. That’s why one of the key principles of the search-based effectual method includes iteration and testing. This is really just your first “loop” or “diamond” or “iteration” to get you started.

Designers love good questions because they stimulate progress. Your brainstorming phase should include asking yourself a number of questions such as “Do I want to stay in Toronto?” “Do I want to work in a big or small company?” “Do I want to work in a graphic communication company or do I want a graphic communications role inside a company that does something else?” “Do I want to be the only graphic artist at a company or do I want to work with a lot of other graphic artists?”

You can see examples of other students’ assignments, along with feedback, by watching the previous term’s in-class feedback sessions posted on D2L.

ECLD Tool #1: Wheel of Life Step-by-Step Review

- Draw your Wheel and document your current activities using post-it notes (or other digital alternatives) on Your Wheel of Life (what currently occupies your time, what are your current interests, obligations, activities, jobs, chores and time spent on?).

- Go around the Wheel again and brainstorm any new activities, interests, goals or values you would like to pursue (use post-it notes to get a nice number of divergent thinking topics to work with).

- Go around each pie-shaped element of your wheel and Rate Level of Satisfaction, Need for Change, or Challenges in Each Slice of Your Wheel (what changes can you envision to make progress toward achieving your desires?).

- Look for Patterns during the Convergent Thinking Phase. Now that you have 30+ post-it notes, you can remove them from the wheel and use visualization methods to identify patterns, plot them on different axes and see if you find anything insightful or beneficial to you.

- Cluster, Separate, Label and Add New Post-Its

- Remove the post-its from your wheel and rearrange them along either a single line or into 2×2 matrices such as:

- Importance

- Importance toward achieving your Career-Related Design Challenge

- Urgency

- Need for Change

- Long-term vs Short-term

- Things You Want to Do vs Don’t Want to Do

- Level of Interest or Excitement

- Capture the Learning

- Focus on your Career-Related portions of the Wheel and condense the information into Potential Design Challenges you face regarding:

- Job Search, Intrapreneurial Opportunities

- Side-Hustle, Startup, Self-Employment, Gig

- Social Capital, Social Venture, Changemaking Projects

- Human Capital and Character

- Overall Balance

- Focus on your Career-Related portions of the Wheel and condense the information into Potential Design Challenges you face regarding:

-

- Identify your Top 3-5 Career and Life Balance Design Challenges

- Pick the most important career-related design challenge as your first draft and expand upon it to turn it into a Good Design Challenge Question

- Document Your Process (Take Photos of Your Work)

- Iterate to Improve Your Wheel of Life and Capture any Insights

- Write a Report for the course assignment that meets university standards and includes Table of Contents, Introduction, Background, Next Steps and other relevant sections to help us to help you

Upload Your Work to D2L at least 24 hours before class if you would like Public Feedback (Please Note that You Must Agree to Open Access Sharing for such Feedback)

Goal-Setting and Time Management Skills

When searching for and discovering what you might be passionate about, it is important to always keep the Bird-in-the-Hand principle in mind to ensure that your goals are realistic and you are growing your character, human and social capital (as well as your financial capital of course). You still need to set goals, but often these are more hypotheses or general directions to explore. Some goals are fairly easy to reach with minimal experimentation, searching or decision-making. For example, getting a university degree is a fairly straight-forward goal to achieve and almost entirely within your complete control to attain (once you get accepted by a university, all you need to do is sign up for classes and do the assignments, both of which are almost entirely within your control). Other goals are somewhat outside of your control such as getting the perfect job (the employer may hire someone else) or the perfect spouse (the other person may not love you back or may not want to get married). Many goals require a combination of search-based effectual principles combined with more traditional goal-setting and time management planning skills.

Good goal-setting will help you take control of your time and find a way to fit all your hopes, dreams and desires into your busy life while maintaining balance and keeping all the pieces of your life in context. Goal-setting and time management tools are essential elements of productivity, success and happiness. I know that most of you have had some introductory classes or lessons in goal-setting so let me give you some additional advanced knowledge. It’s a foundational skill but hard to master. I’ve personally read well over 100 books on goal setting and I’ve been applying it for over 25 years. Trust me on this, we can all use more practice.

Goal-setting theories originally arose as fundamental aspects of the planning-based causal reasoning approach to management and happiness. You still need goals for search-based effectual thinking, but we call them hypotheses instead of goals. Instead of knowing your goals in advance you can use experimentation, surprise and serendipity to discover them. Instead of single-mindedly pursuing them, we instead test them against reality to discover if they are good goals or if we need to “pivot” in another direction. You still need goals, but they are more malleable! Even if you don’t know your long-term goals and are searching to discover your values, you still need to set short-term hypotheses to guide your day-to-day actions.

Goal-setting (a.k.a “Intent”) is an essential link between your beliefs and values and your actions. Goals condense and focus your attention in order to guide your actions.

We’ll discuss this in more detail in Chapter 8, but this figure is based on perhaps the most heavily researched and validated model of human behavior. Your core beliefs (like your view of yourself, other people and the world around you) tend to be vague and largely subconscious. Your attitudes, desires and values (like curiosity, proactivity, hope, resiliency, wanting to build a career around sports, work in a fast-paced start-up or make a positive change in the world) are more consciously held, but also tend to be quite vague. Goals help you take these vague thoughts and feelings and focus them like a laser on specific plans and intentions (like signing up for a resume-building workshop or attending a job fair event). Goals are critical to success by helping crystalize a vague value like “work hard and do a good job” into something specific like “compile the monthly sales numbers and send a report by Friday at 5pm”.

In the same way that a laser can focus mere harmless lightwaves into a powerful beam that cuts through steel, goals can transform your vague interests, values and desires into an unstoppable series of actions that can make your wildest dreams come true.

Sometimes we set goals (like going to the gym three times a week) but just fail to do them due to laziness, procrastination, inertia, unforeseen events, poor time management or weak self-control. Psychologists, philosophers and self-help gurus have written hundreds of books about how to actually do what you say you want to do, but we’ll get to that later. For now, let’s get some practice at least identifying how to properly set goals in the first place.

Edwin Locke and Gary Lantham are the most widely-cited goal-setting, motivation and job satisfaction experts in the world. They summarize their 35 years of ground-breaking research on goal-setting in “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation – A 35-Year Odyssey”. They extensively document that the effects of goal setting are very reliable and also very generalizable. “With goal-setting theory, specific difficult goals have been shown to increase performance on well over 100 different tasks involving more than 40,000 participants in at least eight countries working in laboratory, simulation, and field settings… The time spans have ranged from 1 minute to 25 years…” Goal-setting works, and goal-setting theory is among the most valid and practical theories of motivation in psychology.

Not only are conscious goals and motivations the primary drivers of performance, but Locke and Lantham are particularly clear that their experimental results repudiate theories of determinism and behaviorism (such as fate, destiny or divine will) which reject human motivation saying:

“Goal-setting theory states that, irrespective of the subconscious, conscious motivation affects performance and job satisfaction. This is especially true for people who choose to be purposeful and proactive (Binswanger, 1991). As Bandura (1997) noted, people have the power to actively

control their lives through purposeful thought; this includes the power to program and reprogram their subconscious, [beliefs, attitudes and values] to choose their own goals, to pull out from the subconscious what is relevant to their purpose and to ignore what is not, and to guide their actions based on what they want to accomplish.” (Locke, 1995)

The research is clear, goals direct attention toward goal-relevant activities, increase persistence and have an energizing function – “high goals lead to greater effort than low goals”.

Locke and Lantham also “compared the effect of specific, difficult goals to a commonly used exhortation in organizational settings, namely, to do one’s best. We found that specific, difficult goals consistently led to higher performance than urging people to do their best… In short, when people are asked to do their best, they do not do so.” (Locke & Lantham, 2002)

Goals are primarily what guide your daily actions. From a business planning perspective, you don’t revise your company’s plans every day. You set measurable goals perhaps once every quarter or year and they then guide your daily actions until the next review period. When using lean agile design thinking entrepreneurial methods you still set measurable goals, you just set them more frequently (e.g. weekly) and call them a hypothesis to test using experimentation. But you still need to set measurable goals and get them onto your To Do list.

Following effectual entrepreneurial design thinking methods, don’t think of a goal as a static end point that you must reach to be happy. Think of it as a direction to head in or guide to follow (i.e. a Hypothesis) while you experiment, learn and then decide whether to pivot or persevere. Never think of a goal as something you have to do or should do – then it becomes a burden in your life and a duty or demand on you rather than something you want to do. Remember, goals should be positive value driven and not negative pain avoiding. They are meant as a guide to orient you as you experiment. It is certainly true that avoiding a snake will motivate you to run away (“motivation by fear”), but this kind of pain-avoiding does not direct you where to run. Positive goals provide BOTH increased motivation as well as direction.

Big Hairy Audacious Goals (BHAG) – The CN Tower

I’m a sailor and when explaining BHAG Goals, I like to use the analogy of trying to get to a port while sailing on Lake Ontario. If you’ve never been sailing on Lake Ontario, I have to tell you that from the middle of the lake every direction appears the same. The shoreline is flat everywhere you look. You can’t tell east from west by looking at the shoreline.

Whether you want to go to Rochester or Kingston, there is nothing to steer toward so you always drift off course. You have to frequently look down at the compass or check the GPS to see how far you’ve drifted off course. This is especially annoying during a long distance race or if you want to reach your destination before nightfall. However, if you are heading towards Toronto, there’s the CN Tower, once the tallest free-standing structure in the world. Every other direction looks alike, but Toronto has this big, hairy, massive goal that you can see from clear across the lake. You can’t get lost when trying to sail to Toronto – just point towards the CN Tower. Because your eyes are naturally directed toward the biggest thing on the lake, you almost can’t help but steer towards it.

The wind may be in your face. You may need to tack back and forth to achieve your goal. But it is very easy to sail to Toronto because the goal is just so easy to see. That’s the way all goals should be – big and bold and highly visible! Set big goals – they provide greater motivation and performance!

Goal-Setting Process

The extensive literature on goal-setting and happiness also shows that more specific and short-term incremental goals provide a better guide to action and better performance. “Lose ten kilograms” is certainly an objective, but it doesn’t provide a guide to action. Should you exercise more? What kind of exercise? When will you do it and how often? As described in Tool #9, SMART goals help you break your larger, longer-term or more vague BHAG goals into actionable things you can put in your Day-Timer or daily “To Do” list.

So instead of thinking about only one big goal, break them down into an array of smaller, more detailed action items that make positive steps toward the big goal (using the Affordable Loss Principle). “Lose ten kilos” may be the big goal, but “get a gym membership this week” is a more detailed and actionable goal you can pursue today toward losing weight. If the goal is too big or too vague to put onto today’s To Do list, then you need to break it down into smaller goals.

Goals and Intent vs Self-Discipline

One reason why so many people fail to achieve their goals is that they never really, truly intend to keep them in the first place! Many don’t want to set goals because they are afraid they will fail to achieve them and this will make them feel bad or lower their self-esteem and self-efficacy. Others set goals in the same way that many people set New Year’s resolutions – they do it half-heartedly with no real commitment and no follow through. They break their New Year’s resolutions before the end of the month because they never really took them seriously in the first place. Having a Goal is not the same thing as actually having Intent.

It turns out that Intent is not a simple switch that is either on or off. It’s more like a dimmer switch. Just because you say you’ll do something or set a goal does not mean you’ll actually do it! At least not for long…

It turns out that this contradiction between what people want to do and what they actually do has been the subject of study by philosophers and psychologists for centuries. Why do people sabotage their own self-interests? We know that we need to exercise, we value our health, we want to look good, we buy a gym membership, we tell all our friends about it, we set goals and then we just mysteriously fail to do it. Some would call it laziness, procrastination, weakness or self-sabotage.

The ancient Greeks called it akrasia which means “lack of command”. The philosopher Plato believed that people were simply confused over what they really valued – they didn’t truly know themselves and were not in command of their self-understanding. They would claim to value health and exercise, but then, it turns out that they really valued sleeping, relaxing, eating or doing other things more. The cure would be greater self-understanding and use of reason to guide their motivations and pick better goals. Aristotle, on the other hand, believed that these failures are entirely due to a lack of willpower and self-discipline. Some people are either too passionate and cannot control their emotions, or they are too weak-willed and not strong enough to follow through on their desires. Nietzsche believed that a person’s willpower was erratic and needed to be trained through self-discipline to align our desires and interests with what is good for us. Freud wrote that our unconscious minds (which developed and became fixed during early childhood) worked to undermine and subvert our conscious desires and negatively impact our proper behaviours and emotional responses. Skinner and the Behaviourists theorized that goals and motivations are not as important as learning through stimulus and response (e.g. reward good behaviors and punish incorrect behaviors). The Stoics embraced adversity and hardship as a way to enhance self-discipline and goal attainment (i.e. no pain no gain!). Eastern Kaizen methods use small incremental process improvements, habit and a zero-tolerance of failure. [If you would like to know more about these foundational ideas, I can suggest “Philosophies on Self-Discipline: Lessons from History’s Greatest Thinkers on How to Start, Endure, Finish and Achieve” by Hollins (2021).]

A I said, I’ve read hundreds of books on goal-setting, self-discipline, positive psychology and happiness. A lot has been written about this topic and everyone has their favourite system that seems to help them set, follow through and achieve their goals. Here are a few of my favourite tips:

- Use frequent mini rewards to reinforce your accomplishments. This can include tracking your progress (it’s rewarding to see that you exercised 5 times this week on your chart or Day-Timer) or giving yourself a treat.

- Break long-term goals down into smaller, incremental gains.

- Use the power of ritual and habit.

- Don’t rationalize or justify negative behaviours or make excuses. Own your failures.

- Articulate the values behind your goals (don’t focus on the exercise itself, focus on your health and how good it will feel after you have exercised).

- Focus on building your willpower and self-discipline as its own reward.

- Embrace adversity and hardship as something that makes you stronger.

- Re-frame or shift your mindset about what you consider to be pleasurable.

- Expect your goals to be hard and expect it to be hard to stay on track, that way you are not upset or disappointed when hurdles arise.

- Explore your subconscious beliefs and re-program your own beliefs. Negative beliefs such as “I’m lazy”, “I’m worthless”, “life sucks” or “nothing matters anyway” will sabotage your ability to follow through on goals (this will be covered later in the course).

- Use Positive Self-Talk (such as ECLD Tool #10)

- Set up your life and environment to support your goals (the people around you, your work space, the music you listen to, the time you work on things). Remove temptations.

- Budget your self-discipline wisely. Don’t have too many goals at once. Give yourself a break.

- Use small continuous improvements rather than try to make big changes.

- Surround yourself with people who support your goals.

- Use better Goal-Setting Methods (such as ECLD Tool #9 – coming up next).

Extensive research and testing have shown that having goals is absolutely critical to success and the higher the goals, the higher the performance. If we set low goals or no goals, we get low results. If we set mediocre goals, we get mediocre performance. If we set high goals, we get the highest performance. Regardless of whether or not we are setting annual goals or short-term hypothesis goals, the key is to set high (but not impossible) goals in the first place and then to act on them by developing good habits and building self-discipline. [In ECLD Module 11, I give an example of my apparently simple goal to drink more water and how I needed to form a new habit rather than simply set the goal itself. Willpower and self-discipline alone were not enough for me.]

Tool #9 Goal Setting and Time Management

Watch and Use Tool #9 – Goal-Setting & Hypothesis Testing (19:38) I suggest you watch and complete Tool #1 before you begin to watch and complete Tool #9 as part of Assignment #1.

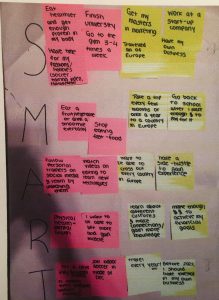

Start with your major design challenges from your Wheel of Life and use divergent thinking tools to generate potential goals and hypotheses for things you can do over the next 1-10 weeks to take a positive step toward them. For each of these ideas, check to see if they are specific enough to write down and be completed in a single day. Something like “get a job” could take weeks or months whereas “make an appointment with the BCH to have someone review my resume” can be done in a single sitting. Similarly, “study for a test” or “write a final report” is too vague and may take several evenings of work to complete.

If the goal or idea is too big, you may need to use a Mind-Map or other technique to break it down into a number of manageable chunks. A good framework for screening to make sure something is specific enough is the SMART framework.

If the goal or idea is too big, you may need to use a Mind-Map or other technique to break it down into a number of manageable chunks. A good framework for screening to make sure something is specific enough is the SMART framework.

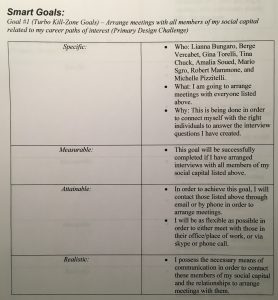

SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Action-oriented, Realistic and Timely. Note that ‘A’ stands for Action instead of Attainable which is already covered under Realistic (this is a common mistake that many students make). Look at any goal and see if it meets all five criteria. If it doesn’t, then continue setting smaller and more Specific, Measurable, Action-oriented, Realistic and Timely goals until you get it down to something small enough to potentially fit onto today’s To Do list. There’s nothing wrong with having a lot of vague, high-level, broad or long-term goals – these are good for yearly or monthly goals, but we’re trying to ensure you then break it down small enough to fit into your day-to-day life.

Saying that you “want to find a job” is a good goal but it doesn’t tell you what to do today. You can redefine this as “set up 6 job interviews by next week” which is better but still pretty vague – it is not S (who will the interviews be with?), nor is it A (what actions are you supposed to take?). Most of your goals don’t “need” to be SMART. Sometimes you want them to be a bit fuzzy like “figure out who to interview”. So you need both high-level as well as very detail-oriented SMART goals.

There are a couple INCORRECT ways of using SMART goals that I see a lot. As shown in the figures here, some people describe one goal as being specific and another one as being realistic and yet a different one as being timely. Another incorrect way is to give one goal and then explain in separate descriptions how it is specific, realistic or timely (as though they were trying to convince the reader that it’s a good goal – you don’t need to try to convince others of anything, these goals are for yourself and must be useful to you). The correct way is that each goal should be screened against the criteria of being SMAR &T. Some will (and should) be SMT, others will be MR, others are SMRT. But making at least some of your goals SMART will help ensure you get them onto your daily To Do list and check them off to ensure you are making progress toward those bigger goals.

If you think all of your goals are SMART then you are almost certainly doing it wrong. Most of the smaller short-term and highly specific goals on your To Do list should be SMAR and T.

INCORRECT ways to use SMART Goals

Next, look at what is already on your daily To Do list and see how your SMART goals compare with them. You may need to shift around (or not do) some of your less important To Do items to make room for the goals you need to achieve to make progress on your 5 most important design challenges in your life. A good way to do this is to compare your SMART Goals and other To Do items on a 2 x 2 matrix of Importance vs apparent Urgency. [NOTE: you may want to do this with your long-term goals first (as part of the Wheel of Life) instead of your SMART goals. Each person is different. If you are having trouble with too many SMART goals, then try this on your high–level goals instead.]

The Pilot-in-the-Plane principle says to focus your time and attention on things that are within your control. You can’t control time, but you can control what you choose to do with it and the support systems you set up around time management. Don’t waste time and energy on those things you cannot change. Focus on the things you CAN control like distractions, time robbers and your own procrastination. You can also concentrate on higher value activities that enhance your efficiency and personal productivity.

Have a look again at your goals, and determine which of these are high leverage Quadrant II activities (upper right corner as described in the video for Tool #9). These are goals that will make you more effective in the long run. They might be difficult and inconvenient to do today (like building your social capital), but they really pay off. A classic example of a Quadrant II activity for a manager is hiring and training people to do some of the things you must currently do yourself. You have to stop doing what you are doing and devote the time to hire and train. This makes you less productive now, but more efficient later. There are many such goals that ultimately enhance your effectiveness but are inconvenient in the short run such as exercise, building better relationships, joining an organization, getting proper rest, reading, watching a video on how to do something more efficiently, or compiling your class notes into more useful study aids.

All these high leverage activities are important to your long-term effectiveness and happiness, but are never urgent. You can always exercise tomorrow, go to a networking event next week, hire that new person next month, or focus on an important relationship next term. You can always find a way to procrastinate or put off these important goals and instead “waste” your time on lower value activities like Quadrant III and IV (lower left and right corners as described in the video for Tool #9). You should try to stop or defer doing Quadrant IV activities and change your habits around Quadrant III. The classic example of a Quadrant III activity is allowing yourself to be distracted by the text message, email or phone call that you just received when you know you should ignore it and continue to focus on a matter of higher value to your life like a Quadrant I or II activity. If you don’t have any high leverage Quadrant II goals, go back and set some!

You’ve all heard the story about trying to fill a jar. If you fill it up with rocks is it full? Of course not. You can add some smaller pebbles. Is it full now? Of course not, you can still add some sand. Finally, you can fit in even more by adding water. The problem is if you first fill your jar with water, sand and pebbles, there is no room left for the rocks. You must fit your big rocks into your daily agenda first and these are your Quadrant II goals!

When do you work on these Quadrant II goals? During your peak productivity time of day. Do them when you are at your best – don’t try to squeeze them into the end of your day when you are tired. Everyone has their own personal peak productivity time of day when they are most awake, resilient and effective. Don’t let any so-called “guru” tell you that you have to do important things at 6am because “the early bird gets the worm!” That might have worked for them, but it might not work for you. Personally, I’m useless before 10am and at least one cup of coffee! My peak times are around 10am-1pm and 4pm-7pm. I used to have another peak from 10pm-2am, but I try not to work in the evening anymore because it ruins my sleep.

Find your peak productivity time of day and block it off in your calendar. Try to avoid having meetings, answering phone calls, or looking at email during your peak times of day. I turn off my phone, notifications and email entirely during my peak hours. These are usually low value activities (the sand) that you can easily batch-process and squeeze in during your off-peak times.

Tool #9 – Goal-Setting Step-by-Step Review

- Start with your major design challenges from your Wheel of Life and generate ideas for potential goals and/or hypotheses that you can do within the next 1-10 weeks to make progress on your design challenges. You can create post-it notes, draw freehand figures, or write your goals/tasks down on a list – whatever works best for you.

- For each of these goals/hypotheses, create a series of increasingly specific goals (some may be MT, SMT, SMRT…) until you craft some that can be completed in a single day. If they are too long-term, vague or broad, you may want to use a Mind-Map or other method for breaking down the larger goals into smaller tasks.

- Use the SMART framework to set specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic and timely goals for your 5 major design challenges that can be completed in a single sitting. You may want to set goals for things like: how many people you will meet with, how many networking events you will attend, and how much time you will devote to resolving your design challenges.

- Transfer your SMART goals onto a 2×2 matrix of Importance vs Urgency and add the other major things you need “To Do” during the day. Evaluate which things you can eliminate (Quadrant IV) or change habits and batch-process to become more efficient (Quadrant III).

- Create time in your Day-Timer (or calendar or agenda or “To Do” list or other system that you use to make sure you do everything you need in your busy life) to “Get the Big Rocks In!” during your Peak Productivity times to focus on your Quadrant II goals.

- You should have a running list of annual, monthly and weekly goals to make sure you don’t forget anything. Categorize these by long or short-term goals like “Bucket List” for BHAG goals that you would like to do someday to “Turbo Kill-Zone Goals” for things you plan to do right away.

- Document Your Process (e.g. Take Photos of Your Work). Be sure to include in your report a section for “So What?”, “Insights Gained” or “What I Learned”. Write a Report for the course assignment that meets university standards and includes Table of Contents, Introduction, Background, Next Steps and other relevant sections to help us to help you.

Upload Your Work to D2L at least 24 hours before class if you would like Public Feedback (Please Note that You Must Agree to Open Access Sharing for such Feedback)

Upload Your Work to D2L at least 24 hours before class if you would like Public Feedback (Please Note that You Must Agree to Open Access Sharing for such Feedback)