Main Body

Body Mass Index

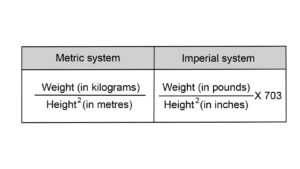

Body Mass Index (BMI) is an anthropometric body measurement that is calculated by weight divided by height. See Figure 3 for the formula based on the imperial and metric system calculations. Adapted from WHO, Health Canada (2003) describes the following categories of BMI:

- Underweight (BMI less than 18.5) – increased risk of developing health problems.

- Normal weight (BMI 18.5 to 24.9) – least risk of developing health problems.

- Overweight (BMI 25 to 29.9) – increased risk of developing health problems.

- Obese (BMI 30 and over) – high risk of developing health problems.

However, Obesity Canada (Rueda-Clausen et al., 2020) outlines recommended BMI classifications that take into consideration ethnicities. For information check out the Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines on pg. 3 for information related to South-, Southeast- or East Asian ethnicity.

Also, you can check out the nomograms provided by Health Canada, called the Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification in Adults – Quick Reference Tool for Professionals.

Steps in measuring BMI are:

- Measure height and weight.

- Calculate BMI based on formula outlined in Figure 3. Round the BMI to one decimal point. For example, if the client weighs 50 kilograms and is 1.5 metres, then the BMI is: 22.2. If the client’s weight is 160 lbs and is 5.2 in feet, then, the BMI is: 29.3.

Figure 3: BMI formulas

Knowledge Bites

Although it is important to be aware of this formula, it is essential to be aware of how it is a flawed and racist health standard particularly for people of colour and for people with high muscle mass.

Let’s start by briefly reflecting on the origins of BMI, which will help you begin to understand its limitations.

BMI is commonly known as an indirect reflection of total body obesity. Originally, BMI was developed based on data from European populations of white men (AMA as cited by Tanne, 2023; Stewart, 2022). This is an important point considering that body shape, structure, and composition are influenced by factors such as sex, race, and age (Tanne, 2023). For example, people who are Black have higher levels of bone mineral content and density than people who are white (Wager & Heyward, 2000). In addition, it has been found that in comparison to white women, Black women have muscles and bones that are heavier and have an increased quantity of body water (Aloia et al., 1997). Also, the BMI measurement can’t differentiate fat from muscle (Karasu, 2016). As a result, someone with increased muscle mass may be identified as obese according to the BMI standard. Additionally, people who are South Asian typically have smaller body frames which influences BMI (Nair, 2021). These differences make a measurement such as BMI (which focuses merely on weight and height) an inaccurate measurement of body fat and obesity.

Despite Billewicz and colleagues writing in the 1960s that formulas like BMI couldn’t measure fat, it still remains a well known and commonly used measure in today’s society to identify obesity (as cited in Karasu, 2016). It is only recent that organizations such as the American Medical Association (2023) have finally highlighted that BMI alone is not appropriate for measuring body fat and that it doesn’t take into consideration differences across age, sex, and race.

Contextualizing Inclusivity

If using BMI in your practice, keep in mind that you need to use the sex assigned at birth in the trans and gender-diverse population when determining a client’s normal BMI. This can be quite distressing for some clients so it is important to be sensitive to this. There may be weight requirements for certain gender-affirming surgery making a sex-based measurement such as BMI problematic in this population.

Health Canada (2003) indicates that the BMI classification system should be used carefully with certain racialized groups, people with lean or muscular builds and those over 65 years of age. If BMI data is collected in the setting you work, it is important to have a critical eye in how you use it and possibly draw your colleagues’ attention to its limitations particularly with racialized groups. Additionally, be aware of how the data may affect different clients from an emotional, psychological, and physical perspective. For example, some Black adolescents are constantly told to lose weight because their BMI is high. This can be distressing for them, and can result in mental health issues, eating disorders, and maladapted healthcare seeking behaviours (i.e., avoiding going to health care visits).

Based on the North American standards for BMI, it may appear that many Asians have a lower incidence of obesity. However, in a study on Asian Americans, it was noted that they are more likely to gain weight centrally which is associated with comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Li et al., 2022). Lower cut-offs for BMI for Asians may be needed to better reflect the difference in patterns of adiposity (Li et al., 2022).

Cases to reflect upon:

(1) A young black female was assessed as being overweight based on the original BMI scores. This led to the young female joining a weight loss program and losing most of the required weight. However, when she got to what was considered the high end of her weight range, her family became extremely concerned because she was becoming very thin and rather gaunt. A family physician was consulted and indicated that her weight loss be considered successful at the top end of the scale.

(2) A college football player has a low body fat percentage but a BMI of 33. As the healthcare provider, you may recognize that this BMI is in the obese range. Without acknowledging the limitations of BMI measurements, one might suggest a lifestyle change. However, it is important to recognize that BMI cannot differentiate between muscle and fat.

Priorities of Care

If someone’s BMI is high or low, you should have a discussion with the client focusing on their health and well-being. It is important to ensure they are an active partner in the discussion and the health decisions made. When engaging in discussions, be sure you consider social determinants of health such as food security. If someone isn’t food secure, you should consider discussing resources that may support them (e.g., food banks and certain healthy alternatives). You should also consider trends in BMI and whether there has been a trend upward or downward; thus, comparing the measurement to previous BMI is important.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

References

Aloia, J., Vaswani, A., Flaster, E. (1997). Comparison of body composition in black and white premenopausal women. J Lab Clin Med, 129(3), 294-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2143(97)90177-3

American Medical Association (2023). AMA adopts new policy clarifying role of BMI as a measure in medicine. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-adopts-new-policy-clarifying-role-bmi-measure-medicine

Health Canada (2003). Canadian Guidelines for Body Weight Classification in Adults: Quick Reference Tool for Professionals. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/fn-an/alt_formats/hpfb-dgpsa/pdf/nutrition/cg_quick_ref-ldc_rapide_ref-eng.pdf

Karasu, S. Adolphe Quetelet and the evolution of body mass index. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/the-gravity-of-weight/201603/adolphe-quetelet-and-the-evolution-of-body-mass-index-bmi

Li, Z., Daniel, S., Fujioka, K., & Umashanker, D. (2023). Obesity among Asian American people in the United States: A review. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 31(2), 316–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23639

Nair, T. (2021). More than skin color: Ethnicity-specific BMI cutoffs for obesity based on type 2 diabetes risk in England. American College of Cardiology. https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2021/10/18/15/35/More-Than-Skin-Color

Raphael, D., Bryant, T., Mikkonen, J. and Raphael, A. (2020). Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts. Ontario Tech University Faculty of Health Sciences and Toronto: York University School of Health Policy and Management. https://thecanadianfacts.org/The_Canadian_Facts-2nd_ed.pdf

Rueda-Clausen, C., Poddar, M., Lear, S., Poirier, P., & Sharma, A. Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines: Assessment of People Living with Obesity. Obesity Canada. https://obesitycanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/6-Obesity-Assessment-v6-with-links.pdf

Stewart, S. (2022). The racial origins of BMI. Anti-Racism Daily. https://the-ard.com/2022/04/05/the-racial-origins-of-bmi-weight-measuring/

Tanne, J. (2023). Obesity: Avoid using BMI alone when evaluating patients, say US doctors’ leaders, 381, p. 1400. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.p1400

Wagner, D., & Heyward, V. (2000). Measures of body composition in blacks and whites: A comparative review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 71(6), 1392-1402. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1392