Digital Photography for Graphic Communications

Chapter 1 • Introduction

A long time ago—longer than many of us can remember—print jobs were produced from hardcopy known as mechanicals. Graphic communications was a slow and steady giant; nothing changed for years.

Then, in 1985, print production was turned upside down by the introduction of the Macintosh computer, the Apple LaserWriter printer, and Aldus PageMaker page-layout software—and the word “digital” came to printing. Who knew that a string of zeros and ones could alter graphics completely? First type became digital, then layout, and today photography.

Prior to digital photography images were captured on film, and scanned in or “digitized.” Further back, color separations were made with enlargers or process cameras equipped with red, green, blue, and visual (white) filters. The first digital cameras were developed by NASA in the late 1970s so astronauts could send pictures from space. By the mid 1990s, they were being commercialized. Their low resolution made them unsuitable for print production. They were also expensive, awkwardly sized, and battery gluttons, and the average camera only held 30 images. Unless you had a computer handy, it was easier to carry extra rolls of film.

Improvements in resolution, size, battery life, memory capacity, turned digital cameras from toys into tools of the trade. Scanning has become a process of the past, and digital cameras are becoming the primary vehicles of image capture. The technology has developed so quickly that our processes need to catch up—particularly from the production perspective.

Now, image capture has become the responsibility of creatives, who have traditionally not been responsible for the accurate reproduction of their work. They have taken over for color trade shops and prepress houses, who manipulated and corrected scanned photos.

Although numerous trade books are available on photography and digital cameras, none have been specifically written for the graphic communications industry, or in particular, for those who now use digital cameras to do work that was once done by a scanner. Thus, this book attempts to address the many considerations of digital photography as a graphic reproduction, rather than as an aesthetic, medium.

Industry Trends in Color Imaging

Digital photography has come to replace scanning in graphic arts for several reasons (Figure 1-1). First, cameras have been increasing in quality and declining in cost, particularly the 6–12 megapixel digital SLR (single-lense reflex) category. Second, digital photography offers greater production speed by avoiding film processing and cleaning, mounting, and dismounting of film or prints. Third, digital photography offers higher image quality by avoiding dust and artifacts and by providing a truer color match to the original scene. Finally, of course, digital photography offers real-time results. The image can be previewed immediately on the camera’s LCD panel or in a studio situation the camera may be tethered to a computer screen. Digital camera systems can also display in real-time the image histogram, thus allowing for technically correct exposures.

As a capture mechanism for print, major considerations in digital photography include the number of megapixels required for reproduction (Figure 1-2) and the quality of captures as determined by exposure, white balance, application of ICC profiles, and other settings. These issues require photographers with knowledge of digital equipment and its use in graphic reproduction.

Current Camera Technologies

Digital cameras have been classified by PIA/GATF into three categories: consumer, prosumer, and professional (Table 1-1). Megapixels and costs are stated for comparative purposes only, as every year new cameras are introduced at a lower cost and with high resolution.

| Camera Type | Format | Megapixels | Cost |

| Consumer | point-and-shoot | 10–20 | <$500 |

| Prosumer | professional point-and-shoot, DSLR or mirrorless | 12–36 | $500–$3,000+ |

| Professional | full-frame DSLR, medium format, or view camera with digital back | 24–40+ | $3,000–40,000+ |

Camera Requirements

The main requirement for a digital camera used for graphics reproduction is sufficient resolution, measured in megapixels. The camera must be able to capture enough pixels for the required image resolution, based on the number of pixels per inch required to support the printed screen ruling. For example, an 8.5×11-in. magazine page printed at 150 lpi requires 300 ppi image resolution, necessitating a digital camera of at least 8.5 megapixels. Users should be aware of the difference between real pixels and interpolated pixels. Often manufacturers may quote higher pixel numbers than really exist in the sensor, in this instance the vendor is computing new pixel information using software interpolation techniques. Better quality is rarely achieved using interpolated pixel information.

How Graphic Communicators Use Digital Cameras

Since graphic arts professionals use digital cameras as a replacement for scanners, we distinguish between the technical and aesthetic side of photography. The following types of digital photography are useful in the graphic arts.

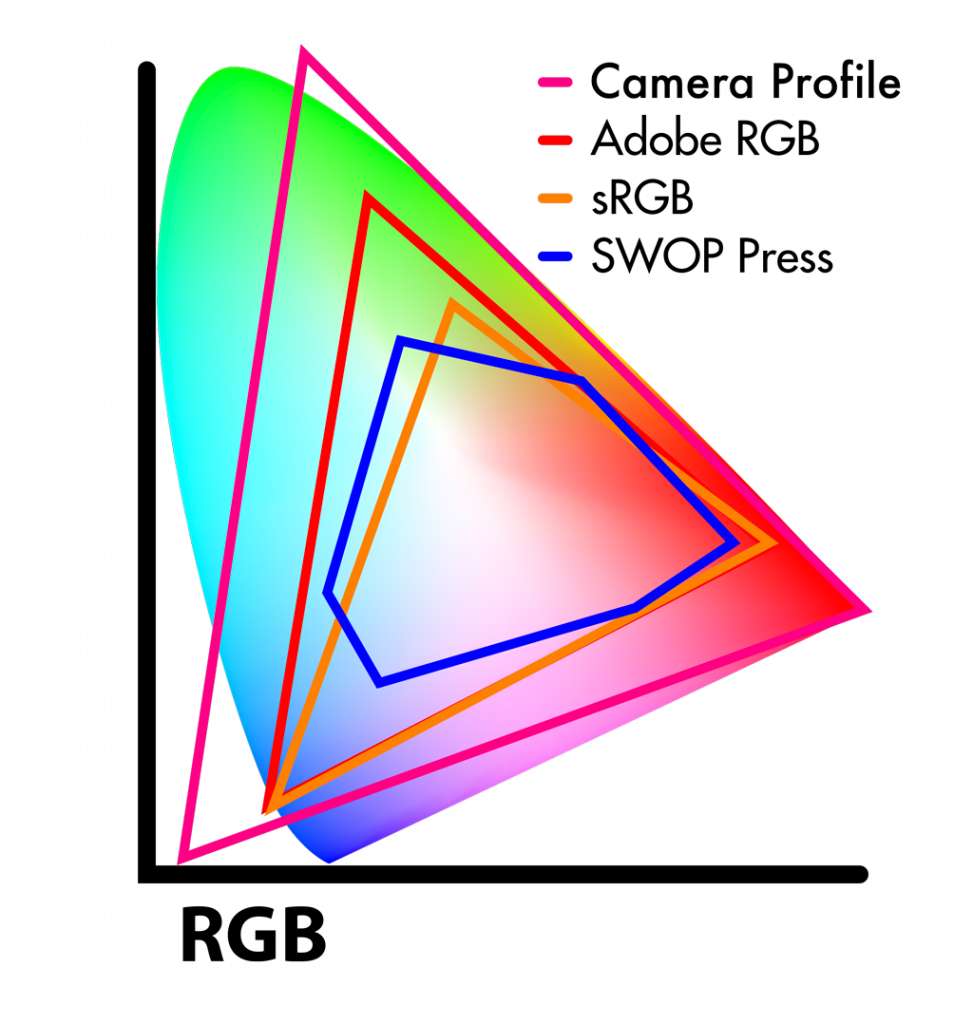

Copy work. Copy work refers to images captured of flat work for reproduction (Figure 1-3 A, B). Examples include logos, photographs, paintings and other artwork. For best results, illuminate copy evenly with lights at a 45° angle to the copy surface to eliminate glare.

Macro photography. Macro photography refers to extreme close-ups (Figure 1-3 C) as might be required for scientific and technical photography, education, training, documentation, or small product photography. Macro photography requires a macro lens, a special lens designed for close-up photography, or a zoom lens with macro capability. How close the lens can focus is usually described as the reproduction ratio. For example a 1:1 macro lens can capture an image on the camera’s sensor that is the object’s actual size. A 2:1 macro lens can capture an image that is half the size of the original.

Product photography. This is photography of small to large items for reproduction in catalogs, newspapers, brochures, flyers, ads, signs, internet auctions, and other reproduction methods (Figure 1-3 D). Depending upon the size of the item, various lighting accessories may be used, including light tents, diffusers, and natural lighting.

Still life. Refers to collections of subjects, whether set up on a table top or on the floor. Examples include artistic groupings of objects or groups of complementary accessories for catalog photography (Figure 1-3 E).

Portrait. Portraits refer to posed (vs. candid) photos of people, individually or in groups (Figure 1-3 F). Examples include yearbooks, biographical head-and-shoulders “mug shots,” and group photos of people. Generally faces reproduce best when photographed with a short-range telephoto lens, as in the 70–120-mm focal length. A telephoto lens compresses distance from front to back, which often flatters the face.

Architectural. This refers to photographs of buildings and rooms (Figure 1-3 G), including photography for real estate brochures and catalogs as well as furniture, decorative accessories, and interior design. Architectural photography can benefit from a wide-angle lens, which captures a wider view of the scene than a normal lens.

Landscape & scenery. This category includes outdoor and scenic photography, as might be used in travel or recreational magazines, catalogs, and brochures (Figure 1-3 H).

How to Use this Book

This book is divided into eight chapters including this introduction. The other chapters are:

Chapter 2, “Equipment,” discusses what the graphic arts user needs for the most common types of digital photography. This includes digital cameras, lenses, lighting, and accessories such as tripods, cable releases, filters, and the like.

Chapter 3, “File Formats and Applications,” discusses the most common file formats used to save digital photographs onto computer media such as hard disks, CD- and DVD-ROM disks, USB “jump” drives, and servers for viewing on the World Wide Web. The chapter also discusses applications used to edit, layout, and print digital photos.

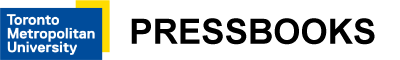

Chapter 4, “Color Management,” describes how to use ICC color management profiles to get the most accurate digital captures, accurate on-screen display, and accurate printed and proofed color.

Chapter 5, “Image Fidelity,” discusses how to achieve images that match the original scene as closely as possible. In this chapter, we refer to image fidelity concepts that were derived from the setup of high-quality drum scanners to help users get the best scan “the first time, every time.”

Chapter 6, “Working with Printers,” eBook Publishers, and Web Designers describes the processes that digital photos must go through to be printed using offset lithography as well as reproduced in eBooks and on the Web. This will be of interest to readers who plan to publish their work in some type of printed media.

Chapter 7, “Pricing Digital Photography,” describes how to estimate for production of digital photographs in a commercial service provider environment, such as a studio or print shop.

Chapter 8, “Working with Photoshop,” describes how to do non-destructive editing in this program.