PART I/THE PRESENT: WHY CANADA HASN’T MADE GLOBAL TV HITS

CHAPTER 1

TV POLICY UP IN FLAMES

“The whole system should be blown open. Let’s start from zero. Let’s see what works and what doesn’t. It will be too late when it lands, the train will have left the station. We need to be asking these questions now.”

Audience, audience, audience

You may know the iconic joke and its punchline: What are the three most important things in the real estate business? Location, location, location. Similarly, there are three factors most vital to the TV business. Audience, audience, audience.

TV is quintessentially and irrefutably a popularity contest. So are other industries including cars, cosmetics, pharma, fashion and more. The only thing that delivers business survival is market demand, which always means meeting the evolving needs of customers. In the TV business, customers are viewers. They demand good stories, well told. Today, reaching large TV audiences means winning an online, global popularity contest with a potential audience of billions for any TV show that may originate anywhere in the world.

If the purpose of Canadian TV policy was to reach large audiences, domestically or internationally, there would be no need for this book. But popularity and a crucially connected term, globality, which combines global reach and popularity, has not been the goal of Canadian TV policy. The nationally bounded 20th century design still endures through the historic changes of the 21st century. In Canada, TV’s decade of digital shift (2010-2020) included four federal inquiries about the impact of 21st century TV global externalities, but no new domestic policy vision resulted. By contrast, these inquiries revealed and emboldened a resistance to changing the framework from one that is driven by supply to one that responds to demand. Even under the stunning conditions of the 2020 pandemic that shuttered production and simultaneously increased demand for TV, what still drives Canadian TV policy is fulfilling domestic supply, not meeting national or global demand.

What are the key differences between TV dynamics seventy years ago and today? Today, delivering a hit has never been easier because distribution is borderless and timeless. The media distribution market is global and global demand for TV is at historic levels, growing everywhere. As such, the original rationale for Canada’s entire policy framework — a small market — has vanished. It is equally true that delivering a TV hit has never been harder because competition for audience attention has never been more intense. Not only must creators now compete with every hit that’s ever been made, compelling TV hits originate, not just in Hollywood, but from around the world. Some of these nations, as explored in this book, include countries with small populations such as Denmark, Israel, and South Korea, who are courting the global audience. Canada has lost time getting into the game that counts now: audience, audience, audience. More than a decade into the streaming era, Canadian TV policy is not seeking popularity. Consequently, millions, if not billions, of dollars that could flow to the system have been left on the table.

Three alarm fire: A TV policy framework up in flames

Technology disruption and the globalization of media markets has wreaked devastation on Canadian TV policy. In other words, a three alarm fire has torched the financial pillars of the 20th century framework: (1) linear broadcasting; (2) cable delivery; (3) monetization by geographic markets. All three sources of money are in decline. What does this metaphor mean? What are its implications?

While understanding that broadcasting and cable are declining technologies is straightforward — with cord-cutters and cord-nevers in the news — some readers may wonder what it means to say that linear TV is monetized by geographic markets. This references the TV business model that monetizes by selling advertising, its revenue source. The price of this advertising is based on the projected potential size of the audience for individual programs in a given geographic area. Moreover, rights to broadcast a program are sold territory by territory, and these geographic locales are known as TV markets. As such, the TV monetization model is a two sided market. The program, in the middle, is merely the bait that attracts two customers: advertiser and audience. Popularity, alternately expressed as attention, is actually the product being sold. This model is the same as social media: If the product is free, the audience is the product. Going back to legacy media — in the U.S. there are about 210 TV markets. All of Canada is considered one TV market, making Canada’s English-speaking TV market of about 28M slightly larger than the two largest U.S. TV markets, the Los Angeles and New York metropolitan areas. The point is that territorial markets have been disrupted by global, online access. The media market has transformed from local to global. For services like Netflix, there is one market: everywhere.

When the triple threat of disruption hit Canada, the policy framework had been entrenched over nearly three generations and more than five decades of overall stability in the global TV industry. In light of this stability, it’s critical to pause the narrative to acknowledge that during those decades, Canada’s TV policy success has been irrefutable. In the 20th century, industry and government worked in partnership to construct a framework that succeeded fabulously. Ironically, this was based on the three real estate success factors: location, location, location. The industry seized the TV dynamics of the era, local monetization, to build two infant sectors to remarkable strength: linear broadcasting and TV production.

The starring instrument of Canada’s framework was conceived in 1970 by Canadian broadcasting entrepreneurs who faced a hurdle starting up the CTV network because they had no audience. Canadian private broadcasters, like CTV, were acquiring rights for popular Hollywood programs. But the problem was that Canadian TV viewers, most of whom lived in Canada’s most populated areas close to the U.S. border, could turn their rooftop antennas, called yaggis, southward to watch the same U.S. hits. Ironically, the spread of cable TV made matters worse, as more Canadians could watch these Hollywood hits directly on the U.S. channels.

Likely inspired by U.S. regulations that protected the value of program rights acquired by local broadcasters, in 1969, CTV executives had a brainstorm while attending the May upfronts in Hollywood. They lobbied the CRTC to protect their territorial rights, which required overturning an existing regulation against rebroadcasting programs. CRTC agreed and the result was bold, policy innovation, a reversal that made rebroadcasting obligatory and was perfectly aligned with the way broadcasting was monetized, i.e. by geographic location. The program was the bait, but the key was that the regulation made it obligatory for cable companies to simultaneously replace U.S. signals (including the embedded commercials) with Canadian signals when both aired at the same time. Bingo: Canadian broadcasters gained the entire Canadian audience for a given show. This process, called simultaneous substitution, boosted the Canadian audience for hits by 30%, which in turn boosted advertising rates that could be charged by Canadian broadcasters. Simsub gave Canadian advertisers a Canadian market in which to sell, and made broadcasters profitable. This one regulatory instrument enabled the building of a robust domestic broadcasting infrastructure but that wasn’t all. Broadcasters would be obligated by CRTC to pay a price for the regulatory gift of audience boost. They would be required to use some of their increased revenues to cross-subsidize the production of Canadian prime time TV. As such, the popularity of Hollywood hits with Canadian audiences became the lure, i.e. the financial mechanism, that built Canadian broadcasting.

The name of this regulation is simultaneous substitution. Often called simsub, I call it AmCon for CanCon (American Content for Canadian Content) because of its inherent paradox: While rhetoric claims to be saving Canadians from U.S. TV, regulation depends on Canadians’ undying affection for U.S. TV.

Simsub put Canadian broadcasters on a par with other North American regional broadcasters, with their business model to acquire popular content well below the cost of production and sell ads at prices that (then) ensured robust profitability. Ironically, simsub also ensured the Americanization of Canadian prime time because it only applies when the Canadian channel offers the same program at the same time as the U.S. border station. Still, the benefits of simultaneous substitution have lasted more than 50 years, enduring as sports and live events replaced scripted TV hits, which are now often accessed online.

Today, the strength of Canada’s broadcasting and cable sectors (sectors now mostly integrated with telecommunication carriers) can be seen in the numbers.7 There are over 70B in revenues. 54B derive from telecommunications, meaning wireline and wireless telephony, data and internet, including broadband. The remaining 17B come from broadcasting and cable TV. The broadcasting numbers are broken out, presumably because radio and TV have been designated, for decades, as required to contribute to Canadian content. Eventually, the cable sector was assigned to contribute 5% of their revenues to CMF; today, other broadcasting distributors like DTH satellite and the telephone companies’ IPTV systems have the same obligation.

With simultaneous substitution enabling money for production, a second, complementary policy was also fundamental to the growth of the production sector: the ten point system. This instrument would also be based on the same three fundamentals as simultaneous substitution: location, location, location. During the years of 1980-1984, the fledgling production sector collaborated with the government to invent a point system that determined how funds from broadcasting would be best deployed to build a workforce that could supply the programs that would become known as Canadian content. The result was that Canada became a world-class media production location that today successfully competes against locations around the world for production business. Canada is the #3 production locale in North America, after Los Angeles and New York. There is substantial spin-off value, beyond the jobs and infrastructure, including hospitality, tourism, and more.

It’s challenging to assess the full financial value of the Canadian production sector because traditional data collection methods obscure the fact that manufacturing content is a cost and not a revenue centre. The same annual CRTC Telecommunications Monitoring Report that delivers telecommunications and broadcasting revenues presents the Canadian content data as a series of “contributions” as a percentage of revenues. Canadian content expenditures represent over 30% of broadcasters’ revenues, with just over 50% of broadcasters’ total program expenditures going towards Canadian content. But this presentation of content expenditures as “contributions” against revenues reflects regulatory obligation, not value. Annual reports from the main funding body, Canada Media Fund (CMF),8 similarly parse financial “contributions” according to language, genre, and diversity, with such contributions in the range of 350M, about half from the cable industry and half from the Department of Canadian Heritage (DCH). Such are the systemic reporting idiosyncrasies of Canadian TV that have long been status quo. In Canada, contact not content has always been king meaning that distribution delivers the revenue and the profits that, in turn, subsidize production.

The production sector’s annual report by the Canadian Media Production Association (CMPA), Profile, provides more data, but calculates value by an unconventional metric: summing production budgets. Variously, it combines TV with film production and/or French and English language production and/or Canadian content and foreign production. For example, the most recent data9 sums total production at 9.3B. This is comprised of 4.9B from foreign on-location production in Canada (including film and TV) and 4.4B Canadian production, which includes 3.2B various categories (film and TV; French and English productions; and all genres) and 1.2B in broadcaster in-house productions. Drilling down further, the report shows English-language Canadian content TV fiction at 1.3B (of the 9.3B cited above), noting English-language fiction represents 79% of Canadian content fiction, which totals at 1.7B (French language TV is 20% and other languages a negligible percentage). While it may be tempting to compare TV production numbers to the 17B broadcasting revenues and 70B total communication revenues, these would be expenditures-to revenue comparisons and not apples-to-apples, making it difficult to assess to what extent the production sector is profitable.

Former Director General, Telecommunications Policy for Industry Canada, Len St-Aubin, observes a nuance in Profile’s Exhibit 3-18, which parses financing by genre, and shows that global streamers do contribute to Canadian content:

“This chart shows that foreign sources invest more money than Canadian public and private broadcasters combined, in two priority genres: English-language fiction and children’s and youth. They also invest more than either public or private broadcasters in documentaries. These are also the three genres that benefit most from public incentives, such as federal and provincial tax credits, and other subsidies that add up to about 40% of the budgets. This data also supports the idea that there is no shortage of Canadian talent to produce for the world stage.”

St-Aubin also notes that the data suggests Canadian broadcasters do invest in original content (beyond news and sports) but focus on genres that they can monetize internationally:

“This data also shows that Canadian broadcasters will invest significantly in original content that responds to market demand — but content that they can monetize internationally, such as lifestyle. This programming does not qualify for Canadian content tax credits and public subsidies, which are premised on independent producers’ IP ownership. For example, in April 2021, Corus announced a sale of their largest ever cache of original content: They sold 200 episodes of lifestyle programming to Hulu.”

Profile also supplies important employment and export data. Jobs are a key indication of the production sector’s strength and a tangible result of the policy regime. There are more than 180,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs in Canada’s TV and film sector combined.10 50,000 are in TV and significantly, about half of the TV jobs are in the so-called service production sector that is not official Canadian content, but is a demand-driven high-growth jobs arena. Since Canada’s total jobs (in every sector) number about 15M, the film and TV sector’s 180,000 jobs represent slightly more than 1% of the workforce. Narrowing to TV jobs in Canadian content, about 25,000 jobs, this calculates to about .15% of the jobs in Canada. Another way to look at this number of jobs is to calculate their public cost. Given CRTC’s assessment of 4B subsidies per year11 to the film and TV sector, the public cost of 180,000 jobs would calculate to about $32,000 per job.

In 2016 the quality of Canada’s production workforce and infrastructure had become so strong that Netflix announced that its first production facility outside the U.S. would be in Canada. Four years later when the 2020 pandemic hit, production employment in Canada was at a record high, partly attributable to Netflix productions. Demand for production workers so exceeded supply that the Toronto Film, Television, and Digital Media Office had put in place an apprenticeship program to train disrupted workers from other manufacturing sectors.12 In September 2020, with the pandemic still raging, Netflix expanded its studio commitment with a large investment in Vancouver. Despite all this, a paradoxical “bite the hand that feeds it” anger towards Netflix continued to swirl. It had begun when Netflix was embraced by Canadian consumers in 2010 and intensified when Netflix opened its virtual production studio in 2016.

The broad stroke is that Canadian TV seems often to be the vortex of a perfect storm where art, business, audiences, publicity and the raw edge of the Canada−U.S. relationship meet. The sector’s power to draw attention, compared to its relatively tiny size, has always been outsized. For example, if TV production is at an all time high, what’s the problem? Purportedly, it’s that the underlying sources of subsidy are in decline. As the metaphor suggests: the flames of disruption are ravaging the framework. Profits in broadcasting and cable have declined from the double digits (1960’s to the 1990’s) to low single digits, and continue to slowly decrease. Inevitably, like the demise of horse buggies or typewriters, these technologies will eventually disappear. The money to fund Canadian content comes from these disrupted sources and the industry appears desperate to replace it.

Another way to frame the problem is that the TV sector — broadcasters, independent producers and policymakers — began to believe their success was, in fact, akin to the real estate success factors: location, location, location. A logical error in this thinking is that location, i.e. the site of manufacturing a show, is always a cost. It is always an investment in a final product meant to reach audiences. The blind spot has been that spending on content to meet regulatory obligations is not the same as investing in content for audiences. For broadcasters, since their profits derive from popular content they do not finance, CanCon spending became the cost of doing business, For the production sector, summing production budgets indicates job creation, but does not demonstrate content sustainability, much less profitability. Manufacturing an ever higher volume of TV indicates supply but is no measure of success if it wilfully ignores demand. The only ROI (Return on Investment) in the TV business derives from one thing: market popularity. A stark irony is that the audience priority is not unknown in Canada because the profits that subsidize Canadian content production have always been the result of the Canadian audience’s demand for Hollywood hits. This irony is being compounded as the data shows an increasing trend for popular Hollywood shows by audience-driven foreign companies to be produced on location in Canada, employing Canada’s world-class talent, crews, and facilities in record numbers.

Popularity IS the media business model

The three-alarm metaphor explains that the locus of TV disruption is in delivery technology. The argument for policy change deepens with analysis of the content side. Why hasn’t a half-century of Canadian TV policy matured the sector to produce programs that are profitable or even sustainable, despite the expenditure of the lion’s share of public money on this one genre? The answer is that policy has not incentivized popularity. Put more simply, why hasn’t Canada made global TV hits? The reason is deceptively simple: It never tried to.

Popularity is embedded in Hollywood DNA, as observed by iconic Canadian showrunner, David Shore, executive producer on the hit series (including in Canada), “The Good Doctor” (Disney/ABC, 2017–), based on a 2013 South Korean show. Shore’s many more credits and awards include creator of the long-running, world #1 series, “House” (Fox, 2004-2012); and many more shows, including the Canadian series “Due South” (CTV and CBS, 1994-1999):

“Ultimately the only thing that matters in terms of getting a global market is pleasing that market. And you need to be scared you might fail.”

Case in point: In June 2020, Banff held a virtual panel. I was excited because it was a showrunner panel, the job that is TV’s cynosure. Given the pandemic surge in demand for TV, I anticipated a lightbulb moment linking writing to popularity. Then I saw the waiting room slide deck. It boasted Schitt’s Creek, created by Canadian showrunners Eugene Levy and his son Dan, and as well known, earned a spot on Netflix where it became a global hit. What upset me was that the slide boasted Schitt’s Creek global and Canadian audience numbers: 3.3M and 1.3M respectively. As a policy wonk, I knew that 1M had been artificially set as a Canadian “hit” in 2004 as a policy decision because Canadian TV shows just don’t exceed that, even though top Hollywood prime time TV hits in Canada (such as House at the time) have regularly exceeded 2M. It’s important to note that an audience of 2M in Canada calculates to 20M in the 10x bigger U.S. market. Moreover, 20M, and whether live or aggregated, has been an audience number that says “hit” for decades.

There are important implications to the Schitt’s Creek triumph. It’s an example of what will happen when strong creative meets global reach and can aggregate audiences. The series’ success is also an indicator of the rising soft power of Canadian culture, with its values of inclusiveness and diversity, non-violence and anti-guns, universal health care, and social cohesiveness — and underscores that the timing is now for TV policy that prioritizes popularity.

It is simple enough to observe that Canada’s policy framework has never prioritized popularity and therefore mostly it has not been achieved. Yet it has been anything but simple to free this problem from deep entrenchment in policy that has evolved into a mediaucracy that is resistant to even acknowledging a need for change. Partly this is because legacy decline has been slow. For the year 2019, revenue from conventional TV stations eked out a positive growth rate of about .8%. And despite the hysteria about cord cutting, cable distribution declined only 2.1%.13 On the advertising side, a ten year review of media advertising in Canada in the decade ending in 2018, broadcast TV advertising only decreased by about 1.4%, from $3.39B to $3.20B.14 The slow pace of decline seemed to allow panic to co-exist without urgency to do the policy work to future proof the framework. But the 2020 pandemic accelerated digital shift and the implication of disruption to a global, online market can’t be softened. A three-alarm fire has ravaged the financial pillars of Canada’s 20th century framework, none of which have pivoted on popularity.

Todd Gitlin’s iconic book about Hollywood prime time TV is an inspiration for this book because it features compelling interviews with development executives. It confirms that popularity has long been the singular value in Hollywood:

“I’m not interested in culture. I’m not interested in pro-social values. I have only one interest. That’s whether people watch the program. That’s my definition of good, that’s my definition of bad.”15

Canada’s policy framework was built to create a domestic supply of TV shows, not to meet a domestic — and certainly not global — demand. But the policy structure doesn’t alter the fact that media, from hieroglyphics on a cave wall or stories around a campfire, has always abided by a singular success formula: popularity. Media popularity is not a “nice to have.” It’s the only media business model and arguably always has been. When great stories are well told, they become hits. Hits are evergreen through time and space. They move audiences to tears, laughter and awe for years, decades, even centuries. Thousands of TV hits include All in the Family, Big Bang Theory, Breaking Bad, The Crown, Downton Abbey, Game of Thrones, House of Cards, I Love Lucy, Seinfeld, The Sopranos, and countless more. Global demand for great TV stories has been the financial cornerstone of the TV business since day one. 21st century TV disruption in distribution technology has created a global demand for content that has never been greater. The abundance, and some say glut, of content available online even calls for revising the Hollywood mantra that content is king. It’s not. Hit content is and always has been king.

Academics have described media as different types of goods including a cultural, shared, or experience good. For me, media is best defined as an attention good.16 All media operates in an economy of attention and relies, for financial success, on the power of market demand, i.e. massive consumption. Here’s my formula for media value. Like all equations, it’s a tautology. Each side implies the other. The formula means that the most important talent in media is the ability to attract audience attention.

MEDIA VALUE FORMULA

T (talent) = A (attention) = MC2 (massive consumption) = $$$$ (media wealth)

T equals the talent to deliver popularity, i.e. attention

A equals that attention

MC2 equals conversion of massive consumption into ratings

subscriptions, clicks, ecommerce, tickets or combination thereof

$$$$ equals the wealth created, when audience attention is converted into money

The most popular TV on the planet is the genre defined in the introduction: the high quality, high-budget, long-form scripted, premium entertainment TV that today is watched anywhere, anytime, on any screen. For more than fifty years, English-language TV has been in the most demand around the world and consequently, has been the most profitable genre. But with the internationalization of TV, even the dominance of English-speaking hits is being disrupted. Today, series shot in many languages, originating in countries around the world, have broken the subtitle barrier and achieved hit status. Foreign language hits are embraced in their original languages — with subtitles — by global audiences, including English-speaking ones. Just a few of many current foreign language hits are Spain’s Money Heist (Antennae 3, then Netflix, 2017–); France’s Lupin (Netflix, 2021 –); and Israel’s Fauda (Yes Oh network then Amazon Prime, 2015–).

I’ve argued for policy with an audience imperative for years, including my remarks about the January 2020 report from the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review (BTLR):

“MIA [Missing In Action] are recommendations for measurable content outcomes such as market performance, in an era when popularity is content’s sole mode of survival and arguably always has been.”17

The argument for the primacy of popularity, and the revenue it would bring, strengthens with knowledge of how much public money has been spent to support Canadian TV for more than five decades — as noted — estimated at 4B annually.18 After decades of support, nearly 40% of every prime time TV show is still publicly funded.19 The outcomes of these expenditures have been a world-class production workforce and a robust broadcasting infrastructure, including many production supply businesses, but few prime time TV shows that would qualify as a global hit. The high-budget TV formerly known as prime time consumes about 60% of public funding from the CMF, yet every program loses money according to a general formula regarding legacy TV that remained unchanged for decades:

“Even after subsidies and advertising revenues are taken into consideration, an English-language Canadian broadcaster averages a net loss of about $125,000 for each hour of Canadian drama and a net profit of about $275,000 for each hour of American-made drama.”20

Canadian audiences still don’t watch English-language Canadian TV. In peak viewing hours, defined in Canada as 7-11:00 p.m,21 about 90% percent of Canadian audiences watch Hollywood TV hits, not shows produced with public funds.22 This data point has also not improved in decades; the latest data indicates a five-year low, reflecting the change in viewing habits to streaming services.

Linear broadcast ratings no longer cumulatively represent audience demand, but they do provide a relative indication of a show’s popularity. An examination of the latest data23 on linear TV indicates that Hollywood hits typically comprise more than 70% of Canada’s top 10 programs and attract 2-4M viewers. The top ten TV shows in Canada for the 2018-2019 season ranged from Big Bang Theory (CBS, 2007-2019 ) at #1 with 2.5M viewers to NCIS (CBS, 2003—) at #10 with 1.7M. It is rare for a Canadian TV show to break into the top ten in Canada. If one does, it tends to be a French-language, Canadian version of a reality-talent show, a genre that is not publicly funded and not insignificantly, a genre whose popularity emerged organically in response to audience demand. The 2018-2019 season confirms this trend: Only one Canadian TV show made it into Canada’s Top Ten overall, the reality show, La Voix (#4, 2M, TVA, 2013—), which is the French language version of the Hollywood hit, The Voice (NBC, 2011—). Audiences for prime-time English-language Canadian shows tend to top out at about 1-1.5M, a trend also borne out by this data, ranging from #1, Private Eyes (Global Television Network, 2016— ) at 1M viewers to #10, Frankie Drake Mysteries (CBC, 2017— ) at 575,000. As mentioned, back in 2004, the perceived popularity ceiling for Canadian TV shows motivated CRTC to define a Canadian TV hit as 1M in order to rationalize increased subsidies to hits. However, 1M is not enough domestic audience for a prime time TV show to break even financially.

Nor is a domestic audience of 1M a good predictor of global popularity. In other small countries, such as Denmark, domestic popularity, sometimes up to 50%, is used to gauge a series’ readiness for export.24 Given this reasoning, it is not surprising that the latest data from CMF25 reports less than 2% ROI on its Canadian content investments: $6.8M on $369M dollars. I believe that if a screen story moves a viewer to laughter, tears, or concern in Los Angeles, London or Lagos, it will do the same in Canada, meaning that audiences all over the world are more similar than different. A shared humanity is the powerful basis of demand for global hits, which explains why the popularity deficit of Canadian prime time TV applies to both domestic and global markets. Canada, one of the world’s most diverse countries, should know this better than most. Canadian producers should be energized by the knowledge that domestic popularity predicts global popularity.

Surprisingly, it turns out 20M has been a remarkably stable audience size, defining a hit in every decade since the beginning of TV. The CBS hit, I Love Lucy (1951-1957) got almost twenty million viewers for top episodes, representing at that time 90% of available screens. In 1964, Bonanza (NBC, 1959-1973) got 19 million viewers, of 50 million TV households. In 1974, All in the Family (CBS, 1971-1979) got 20 million viewers of 70 million households. In 1984, Dynasty (ABC, 1981-1989) got 21 million viewers of 85 million TV households. In 1994, Seinfeld (NBC 1989-1998) got 20 million viewers of 95 million households. In 2004, CSI (CBS, 2000−to date) got 26 million viewers of 108 million households. Seven decades after Lucy, another legendary CBS series, Big Bang Theory (2007−2019) often got 23 million viewers of 116 million TV households, not even counting the multiplicity of TV viewing options on phones, tablets, and laptops. The legacy network hit, The Good Doctor (Disney/ABC, 2017–), executive produced by Canadian David Shore, has attracted more than 18 million viewers in a 7 day aggregation, and up to 2M in Canada. Given the 10-1 population differential, about 20M U.S. viewers equates with the 2M viewers that characterize a hit in Canada, and would rank a TV show in the top ten.26

There is an important nuance to these numbers that is rooted in today’s accelerating TV monetization model: subscription TV, also known as Subscription Video On Demand (SVOD). The unlimited, 24-7 ecosystem has ushered in a new math for hits. Let’s return to Schitt’s Creek, which made Emmy history on September 20, 2020. In the first ever virtual ceremony, with 130 nominees stationed in 10 countries around the world, Schitt’s Creek swept the Emmys, winning every award in the first hour of the broadcast. Its seven awards included outstanding comedy series and outstanding writing for its creators, Eugene Levy and his son, Daniel Levy. The show also won for outstanding lead actor and actress, supporting actor and actress, direction and costumes. What a testament to the rich history of Canadian comedy, going back to Levy’s roots in Second City (1973 — present) and to Torontonian Lorne Michaels whose creation, Saturday Night Live (1975— present), is TV’s longest-running entertainment show, going strong in its 46th season. On the live Emmy broadcast, while Eugene and Dan Levy proudly identified as Canadian and were physically located in Toronto, there was little mention of the commissioning broadcaster (CBC) and not that much about the show’s U.S. distributor, POP, or even Netflix, where the show is distributed internationally and has become a cult hit in Canada and globally — more so since the Emmy sweep. This sends home two points. Firstly, connecting with the idea above, audiences are more similar than different and as such, global popularity begets domestic popularity and vice versa. The second is that today, amidst billions of hours of TV, a program seeks popularity on its own merits, nearly naked, stripped even of its network or year of origin. In an over-abundant ecosystem, popularity is about the show.

A newish math for hits also turns on the way that subscription services monetize. This goes as far back as legendary cable services and shows such as HBO’s The Sopranos (1999-2007); Netflix’ House of Cards (2013-2018); and Showtime’s The Affair (2014-2019). Unlike legacy broadcasters, cablers and streamers don’t sell ratings to advertisers; they sell buzz and convenience directly to consumers and do their audience calculations in the background. Unlike the three-sided market of legacy TV, subscription services are a B2C two-sided market. Major awards watched by large audiences have become a key tool to drive subscriptions. For example, when Showtime’s The Affair won the Golden Globe for Best Drama Series, the estimate of the series’ audience was about 2M, only a tenth of the 20 million viewers who watched the January 2015 Golden Globes show on which the award was announced.27 Although the audience for the 2020 Emmy Awards was an all-time low of just over 6 million,28 this award show’s popularity, global reach, prestige, and media coverage were still valuable tools to drive subscriptions.

Audience is the only thing that counts, but counting the audience necessitates including large and/or tangential audiences such as major awards that create buzz and sell subscriptions. In a global, streaming ecosystem large audiences also means aggregating niche audiences over time and space. Therefore, the popularity discussion leads to the critical importance of global reach.

Globality = global + popularity

The global reach of today’s media market renders the argument that popularity is the media business model even more compelling because it leads to the concept of globality. The word globality combines two words: global + popularity. Globality implies that global reach is a key tenet of aggregating large, online audiences, i.e. over space as well as time. Being guided by a goal of globality implies structuring a policy framework to incentivize TV assets with two capacities — to capture audience attention and be distributed globally.

A globality perspective makes it easy to understand Netflix’ success. A 24-7 online service with unlimited shelf space and spanning 190 countries seeks audiences whenever and wherever. It aggregates content that is popular with niche audiences and transforms it into sufficient global popularity. Remember that Hollywood hits have always had global reach, even during the decades of legacy monetization by geographic territory. Today’s streaming services, given their unlimited content capacity, have opened up the opportunity for TV hits from anywhere in the world to co-exist with Hollywood hits and compete for audiences. This new globality can be traced to Netflix’s first original series, House of Cards (Netflix 2013-2018) that was based on a 1996 British series of the same name. This trend accelerated to include adaptations such as Homeland (Showtime, 2013-2020), based on the Israel series Hatufim/Prisoners of War; The Killing (AMC & Netflix, 2011-2014), based on the Danish show, Forbrydelsen/The Crime and many more. Global demand for content kept growing so much that the so-called subtitle barrier was broken, attributed to Denmark’s series Borgen/The Castle (DR1, 2010-2013). TV hits in foreign languages are now watched by audiences around the world in their native language with subtitles, such as Israel’s Fauda (yes Oh network & Netflix, 2013— ).

Canadians in Hollywood witnessed globality as it began to gain traction. They worried that Canada was losing time by not seizing a historic moment when TV originating from places other than Hollywood was being embraced. Producers and creatives with boots on the ground in Hollywood pointed out that TV from countries including the UK, Norway, Australia, Spain, and many more were starting to deliver hits, while Canada was still depending on production discounts and not stepping up to the opportunity to make TV that would resonate with a global audience. John Morayniss, award-winning Canadian producer and former CEO, Entertainment One Television, saw this transformation as it emerged:

“Australia, New Zealand, the UK, France, and even Quebec had more formats coming into the U.S. than English speaking Canada… Sixty networks in Hollywood were commissioning original programming and represented a great opportunity because demand began to outpace supply.”

I have been advocating for a globality goal for years. At the first of Canada’s four federal inquiries into media disruption, 2014’s Let’s Talk TV, my remarks were titled “CanCon to CanBrand: Let’s pivot our goal from domestic supply to global demand.”29 I’ve argued that policy must pivot from “making shows to making hits in order to seize the thrilling opportunities in the golden, global age of TV.”30 In 2017, when Netflix announced that it had chosen Canada for its first studio outside the U.S., nearly all the press was negative, except mine. I applauded the deal for numerous reasons, but fundamentally because it encouraged the development of Canadian TV that could compete on the world stage. Shortly afterwards, CBC interviewed me. They bolded and enlarged this quote:

“When this era of disruption settles down, Canadian producers will have the same business model that Hollywood has had for years: Make great content and exploit it globally.”31

In the wake of the Netflix deal, I argued for new rules to incentivize globality: “We don’t (yet) have a policy instrument to incentivize content that can win the battle for global attention.”32 I advocated for Canadian producers to be able to access public funds directly, rather than depend on the declining linear broadcasters, who remain the financial gatekeepers. My analysis triggered a response from industry that Silicon Valley would call an immune system reaction,33 meaning a sector’s resistance to change after a long period of status quo. I received the following email from a lobby organization:

“Tues, Nov 7, 2017, 1:52 PM: “Irene. I did read your piece. It concerns me… I guess I don’t understand your premise or what perceived problem you are trying to address.”

To state clearly what had not been clear then, the problem that I was trying to address — and still am — is the policy challenge of incentivizing globality. I had been warned by others in the industry about the immune system, i.e. resistance to change: “There’s a challenge because there’s an old guard and a new guard” and that “the lobby organizations feel very threatened” and would need assistance in understanding how much had already been accomplished and what thrilling opportunities were now just on the horizon. Yet, I admit, that email surprised me.

Faulty rationalizations have continued to gaslight debates on TV policy. A common argument is that a choice must be made between subsidizing the volume of official “Canadian content” versus “foreign” or “service” productions, reasoning that production volume increases quality. There is no data to support this claim and moreover, logic tilts towards the inverse being true: Popularity increases volume. As in most sectors of the economy, popular products increase manufacturing volume via order renewals, bigger budgets, salary increases, infrastructure expansion, and reputation. TV even has a compelling example in the case of the #1 production location, Los Angeles. In addition to being the leading production centre, it is the world’s #1 cluster for creativity. Forcing an either-or choice between official Canadian content or service production seems, to me, a dog whistle to the government for increased entitlements to a sector that has failed to attract an audience. It seems part of a campaign to extend the outdated 20th century protectionist framework into 21st century globality dynamics.

For Canada, the scariest truth about globality may be that access to a global market disappears the very problem that rationalized Canada’s 20th century TV policy framework: a small domestic audience. This rationale no longer applies because the audience is now global. I argue that it’s a good thing the old framework went up in flames so that new dynamics and new opportunities can be exploited. In the final chapter of this book, I demonstrate a path to globality via G-Score, a producer-accessed, platform-agnostic, sliding scale matrix. This policy instrument is designed to incentivize two core elements of globality: content development (R&D) and global distribution (ROI). The basis of this reimagined policy for globality is value chain analysis, and that discussion is next.

Follow the money: Don’t blame the creative

When I began to examine the weak market performance of Canadian prime time TV, I hypothesized that its root cause would be weak creative, i.e. the quality of Canadian storytelling. I was so wrong. Over the decades, Canadian TV’s poor market performance has been wrongly attributed to many factors including small domestic market, small budgets, and even political will. Canadian TV has been called “a riddle inside a mystery inside an enigma.”34 Thousands of pages bemoaned the problem, but no one had followed the money through its value chain. Or compared the Canadian chain to best practices to identify strengths and weaknesses. So I did.

A value chain in any industry describes the linear flow of money that goes into making a product, inception through exploitation. Its three phases are usually conceptualized as research and development (R&D); manufacturing; and return on investment (ROI). Phase 1 and 2 are always costs. Phase 3 represents all the mechanisms for recoupment. These phases map well onto TV. R&D, the first phase of the value chain, is development. In development, both financial and creative elements are assembled because each TV show has a unique plan. Once R&D is approved (in industry lingo, greenlit), phase 2, i.e. manufacturing, i.e. production begins. Ultimately, the project is delivered to the financiers so that phase 3, ROI, can begin, i.e. distribution and monetization.

Following the money through the Canadian prime time TV value chain led to a surprise: the popularity problem is not rooted in the creative elements at all. Canada is teeming with talented producers and writers. It’s not even in the amount of public money in the system (4B per year). The problem is rooted in the structure of the value chain. Structural faults, all of which concern money, are native to the design of the policy framework. There are problems on both ends of the chain, in R&D (development) and ROI (monetization). Problems in development include misalignment of financial interests and an absence of financial risk by key financiers, linear broadcasters and public funds. These R&D faults are further compounded by another fault at the opposite end of the chain, ROI, whereby profits are delivered via a deus ex machina drop-in: Hollywood hits substitute for original content to return ROI to the broadcasters. The necessary linkage between R&D and ROI is also missing, a structural weakness of the chain that results in insufficient pressure to optimize the asset being developed. A close reading of the Canadian TV value chain demonstrates that the flow of money drives creative results. Not vice versa.

This analysis turned out to be more than theory. Its impact is felt by professionals on the ground who understand that the reason Canada doesn’t make hit TV is “systemic and structural.” An A-list Canadian showrunner working in Hollywood, who tried to develop a show in Canada, described the Canadian development experience as “pretend, warped and broken” and “a bridge to nowhere” because the financiers are not invested in making money. Lacking financial motivations, broadcasters are not invested in developing the best possible asset to exploit:

“No one can afford to make television that fails anymore. Except, in Canada when it’s taxpayer money. Who gives a shit because the government is going to give it anyway. The big joke is everyone in Canada says “We’ll get the money anyway. And we don’t have to pay it back…”

A broken value chain reduces pressure on talented writers and even mutes a producer’s need to hire the best possible writer for a project. The result is that development practices in Hollywood and Canada appear superficially similar. However, as noted by David Shore, the underlying dynamics differ:

“I worry about subsidies because they distort the market and reduce your likelihood of something good. Things that appear to be achieving some sort of agenda get approved. The problem is, if you’re in the Canadian market and it’s all financed beforehand, it doesn’t ultimately matter whether it’s good or bad, you’re going to make money either way.”

An important value chain comparator is YouTube, the most popular video service in the world, including in Canada. I led a study of YouTube in Canada35 that included an examination of its value chain and found that the structural link between development and monetization is extremely tight. YouTube’s market feedback loop is so strong that the value chain is best conceptualized as a value spiral, with audience feedback metrics immediately impacting content creation for the purpose of attracting a larger global audience, and so on. As Chapter 3 will explore, one result is that YouTube is bursting with content by Canadian YouTube producers that is popular both domestically and around the world. YouTube’s DNA is globality. Canadian YouTube creators lead the platform in exports with 90% views outside the country, while the platform’s national export average is 50%. Canadian YouTube entrepreneurs successfully compete in the open, global market without public support. The YouTube value chain further corroborates that the Canadian TV market performance problem is due to the policy’s value chain structure, not to the creative.

Value chain analysis definitively solves the mystery of Canadian TV. Structural weakness in the chain is the culprit of poor market performance. In the 20th century, this very structure was a tenacious trade-off that built three robust sectors, broadcasting, TV advertising and TV production. Nevertheless it violates a business fundamental, which is that financiers invest in R&D for one reason, ROI. It will be impossible to upgrade the Canadian TV policy framework to incentivize hits without adjusting the structure to add financial pressure for market performance. The good news is that a structural problem is eminently fixable: change the structure!

Lost time: TV in the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Repairing the value chain will, by default, necessitate aligning Canadian TV policy with — not against — the unstoppable global dynamics of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Well before the 2020 pandemic warped the speed of digital shift, digital technologies had been advancing since the early 21st century. A global, digital playlist already included media, money, mobility, manufacturing, medicine, socializing, shopping and more. Silicon Valley icon, Canadian Salim Ismail, observed that 20 Gutenberg moments, across diverse industries, have been approaching simultaneously,36 each with potential magnitude to be as disruptive to their sector as the 15th century printing press was to communications.

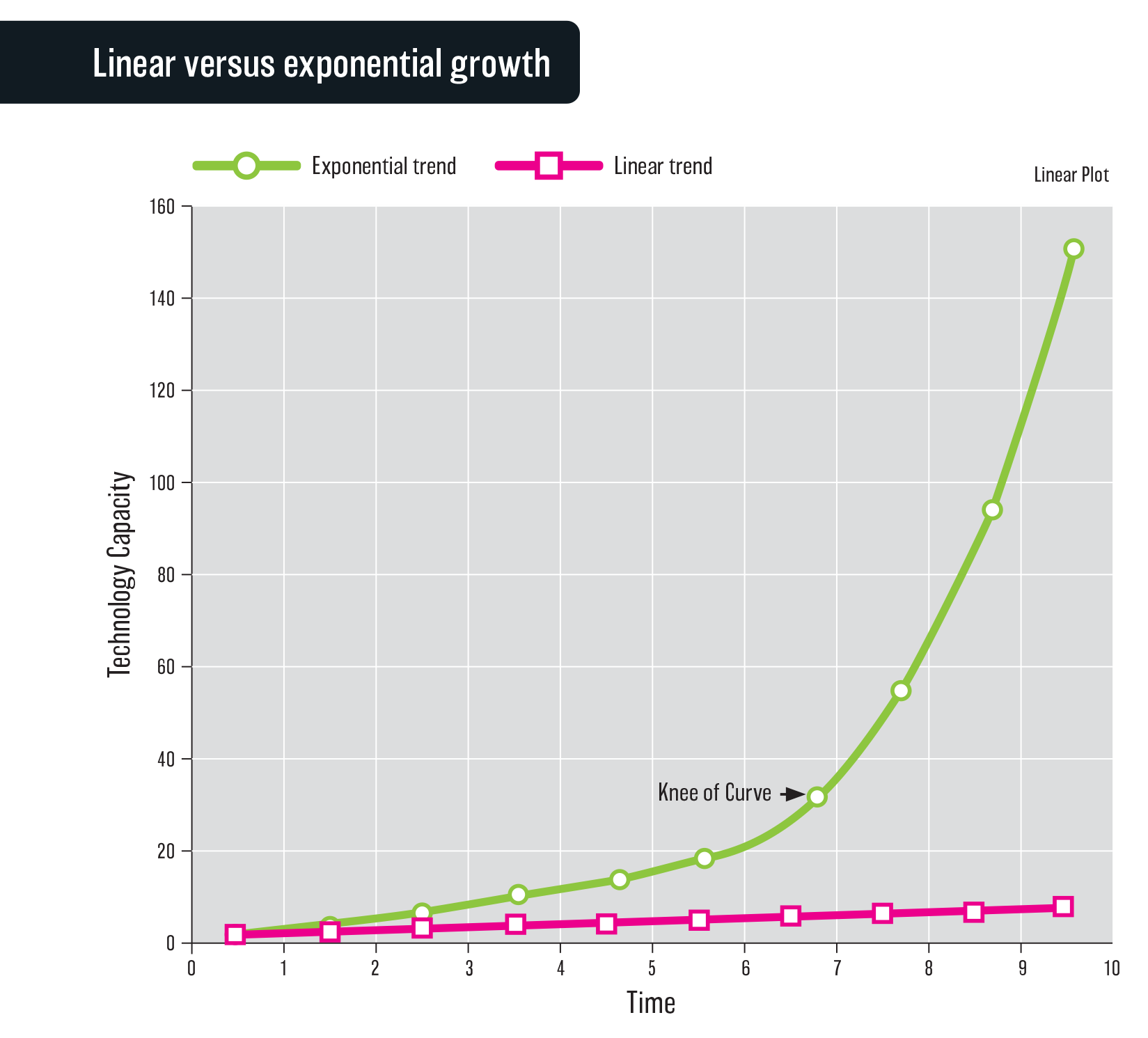

The 4IR was preceded by three previous industrial revolutions, each leading to the next. In the 18th century, the first was marked by inventions like the steam engine that advanced the potential of human work. In the 19th century, a second revolution featured innovations such as mass manufacturing that led to urbanization and set up the conditions for a consumer era. The invention of computing in the 20th century automated math and language, again transforming the potential of human work. Computers cracked German codes and saved millions of lives by helping to end World War II. The next revolution, 4IR, was predicted as early as 1965, by those who understood where computers might lead. A famous paper, eponymously known as Moore’s Law,37 plotted computer progress on a hockey-stick shaped graph, showing that computing capability doubled every year or two and that digital technologies featured a type of growth known as exponential, rather than linear, meaning that growth doubled, rather than proceeded incrementally. In 2001, futurist Ray Kurzweil, later recruited to be a Google Director of Engineering, generalized Moore’s law to all digital technologies, demonstrating that once any industry goes digital, its growth curve will also become exponential. Where is the 4IR headed? With most sectors’ digital progress hovering near the bottom of the exponential curve and most of the digital transformations ahead, it is said we are only 1% into the 4IR, predicted to culminate with merging of the cyber and the biological, perhaps accelerating Darwinian evolution to an era of evolution by design and altering the definition of what it means to be human.

How does TV policy fit into this rather sci-fi story of the 4IR? The connection is that media disruption kick started the whole thing. Media was the low-hanging fruit that could most easily be disrupted from a cubicle-with-a-computer in Silicon Valley. Media was the easiest to digitize compared to other sectors such as manufacturing, money, medicine, and shopping that require partnerships with local infrastructure. The convergence of mail, music, newspapers, and books to electronic screen media has been called a vanilla disruption that started with the digitization of music in the final decade of the 20th century. As each media format became a digital screen practice, old ways were swept away by creative destruction and each sector hopped onto the hockey-stick shaped curve of exponential growth. Online access to media was embraced by consumers, decreasing revenue to legacy delivery technologies. Separate distribution silos converged into one format — a digital screen — and one technology — the Internet.

TV is the most fascinating case because, ironically, the original electronic screen media was the last media format into the pipes. TV remained remarkably stable, resistant to 4IR disruptions for two decades. There were two main reasons, technology hurdles (mainly bandwidth) and TV’s popularity, meaning the amount of money at stake (nearly half of all global advertising). However, with the days long gone when watching TV just meant purchasing a set and choosing from a few free channels to watch, TV had become expensive and complicated, signalling ripeness for disruption that in Silicon Valley is called scope for improvement. Apps like Facebook, YouTube, or Twitter were easy to use, but TV had become infuriating. Even if you could manage to find your show, the remote required tangling with a dinosaur. Hollywood knew the mortal danger facing the TV business, acknowledging that discoverability, i.e. user-friendly interfaces, had become TV’s #1 problem, and if not solved, there would be no problem #2, 3, 4 or 5.39 Still, disruption would take a while to arrive, but would be unstoppable when it did.

Once over the bandwidth hurdle, disruption would proceed to reorganize the TV business world-wide. The faster, cheaper, way more convenient advantages of Internet and wireless delivery technologies were embraced by consumers everywhere. Back in 1950, TV had leapt from zero to 10M TV sets in the U.S. in its first year. Netflix, originally a DVD rental service, was the first mover in online TV. It offered its first streaming subscription in 2007, leapt to 22M global subscribers by 2011; to 30M by 2013; and to 40M by 2015.40

Canadian consumers embraced TV disruption. The Canadian TV industry — not so much. Launching in Canada in September 2010, Netflix signed up a million Canadian subscribers within its first year.41 For Canada’s TV industry, unlike in the U.S., the arrival of streaming, and in particular Netflix, was not a thrilling creative destruction. Online delivery ushered in a triple threat of unintended consequences, or in academic terms, negative externalities that threatened the survival of three dynamics (linear broadcasting, cable delivery, territorial monetization) that just happened to provide the production money. This triplet of events, a.k.a. the three-alarm fire, panicked the industry, even though the Canadian government had predicted a meltdown of the policy model in 2003:

“The Canadian broadcasting system can be likened to a complex machine where the breakdown of a single working part can threaten the functioning of the machine as a whole… In particular [the Committee] is very worried that the existing programming model — which has become overly reliant on the cross-subsidization of Canadian revenues through revenues generated by American programming—will eventually collapse.”42

In Canada, disruption moved slowly, needing to burn through consumer devices and habits. In 2019, revenue from conventional TV stations had slowed to a growth rate of .8%. Despite the hysteria about cord cutting, cable distribution had declined only 2.1%.43

Despite the threats to its distribution model, TV disruption did not significantly alter the demand for stories or the stories themselves. From its origin as a scrappy start-up, Netflix had grown exponentially by capturing demand for the singular genre that has always underpinned the TV industry: hits. People loved great stories exactly as they had since hieroglyphics on cave walls. Even the Canadian government had observed this, saying in 2003 when it predicted the demise of Canada’s TV distribution model: “Storytelling is close to the heart of human culture.”44

By 2018,45 60% of all English-speaking Canadian households subscribed to Netflix. By then, streaming wars had heated up between Netflix and other services such as Amazon Prime, Apple TV+, and more. However, by January 2020, a black swan was exponentially spreading, i.e. a deadly virus for which the world had neither immunity or treatment. By March 2020, the entire world was learning about exponential growth and virality: the kind that kills.

During the 2020 shutdowns, it became obvious how much the planet relied on the global media companies. Not saying they’re perfect, but Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Zoom, Netflix and other digital services kept people and organizations informed, connected, exercised, entertained, and working from home (WFH). Nearly all these services were free to use. Even the cost of Netflix was affordable as an add-on to the essential Internet subscription that now equated, more than ever, to 21st century oxygen. The so-called global giants had no choice but to keep pace with rising demand, and for the most part, they did. Given the reliance on digital during the pandemic, would the techlash be over? Not in Canada, where the industry had not yet acknowledged that the three financial pillars of its policy framework had been disrupted by the 4IR, even though the speed of disruption had accelerated — some said as much as ten years in ten months. In September 2020, as Netflix was announcing an expansion of its presence in Canada with a Vancouver studio, the Canadian government signalled it would make good on its promise to bring global, digital platforms into the 20th century policy framework,46 tabling Bill C-10 on November 3, 202047 that contained legislation proposing how it would do so.

A takeaway from this review of the 4IR is that in every previous Industrial Revolution, Luddites have been on the wrong side of history. As the history of industrial revolutions has shown, it would be impossible, and perhaps should have been unthinkable, for Canadian TV to attempt to harness the changes of the 4IR.

From a policy perspective, the slow walk of TV towards digital disruption has been lucky for Canada, but time has been lost trying to protect an outdated policy structure that no longer serves the needs of Canada’s hard-working, risk-taking talented creators and producers. Arguably, TV’s digital acceleration during the pandemic renders the analysis more urgent.

The argument in this book will go so far as to suggest that Canada is poised to be a global leader in media. Yet, this will require accepting and acting on the analysis of why Canada hasn’t made global TV hits, understanding that it can, how it can, and pivoting from a mediaucracy towards a meritocracy so as to achieve globality. My plan involves a sequence of actionable steps set out in Chapter 7: (1) setting a new systemic goal; (2) specifying a new policy purpose; (3) agreeing on a strategic analysis of the problem; (4) innovating new policy instruments and (5) deploying new measurement metrics to measure the results of the new approach. All this is in keeping with the purpose of this book: to strengthen the Canadian TV industry for a future that has already arrived.