PART II/THE PAST: A 100 YEAR PARADOX

CHAPTER 6

21st CENTURY: FACING BACKWARDS

“Ms. Berkowitz provided a unique perspective on the content issue, stating Canada has never had a lack of talent for content creation, but rather the lack of risk taking and the focus on domestic promotion of Canadian content has held back the Canadian system as a whole. The issue can be summed up in her statement: ‘content is not king, hit content is king.’ In order for Canada to successfully harness the changes in media consumption and production, Canada must look to taking greater risks with new content, invest in the production of hit Canadian content, and make this content available to a global audience.”196

Canada responded to historic global TV disruption in the customary way it had responded to the invention of radio and TV for nearly 100 years: commissions and reports. By now, they’d nailed the process. From 2014-2020, four federal inquiries explored the shift to online TV and the threat to TV financing posed by the decline of linear broadcasting and cable delivery: Let’s Talk TV (LTTV, 2014-2015); Creative Canada (2016-2017); Harnessing Change (2018); and the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review (BTLR, 2017-2020). Each investigated the same dilemma: how should Canada respond? The largest and most anticipated review, the BTLR, tabled its report, Canada’s Communications Future: Time to act, on January 29, 2020, weeks before the coronavirus pandemic shut down the industry and delayed consideration of the report’s 97 recommendations for several months. During all four inquiries and their aftermaths, I was in the room, and/or in print, online, on radio or TV.

2014-2015/Let’s Talk TV

By September 2013 TV disruption was full on. 25% of anglophone Canadians had Netflix subscriptions, and numbers were growing fast.197 Cord cutters and cord nevers were in the news, as was a call for a skinny basic cable package that might compete with Netflix’ price of 10$ per month.

CRTC perceived three irreversible changes: TV technology, TV consumption habits, and a TV policy meltdown. The regulator’s position on these changes had been made clear by then Telecommunications VP, Peter Menzies:

“We can no longer define ourselves as gatekeepers in a world in which there may be no gates. How can we act as an enabler of Canadian expression, rather than as a protector? How can we shift our focus from rules and processes and procedures to outcomes? How can we help Canadian creators take advantage of all the opportunities in the new global environment, in which opportunities may exceed threats?”198

CRTC launched Let’s Talk TV (LTTV) in September 2013 by calling for public participation with a declaration that Canadian TV would not march backwards into the future. One theme, the need for policy change to meet industry change, would remain consistent through the process and would be re-asserted in 2015, when LTTV’s final decisions were announced:

“The roadmap to the future will not be found in the regulator’s rearview mirror… The world is evolving and we must prepare for the future before it is too late.”199

I submitted a precis of my research to the Commission’s call for public participation, arguing that future-proofing the policy framework would require a systemic goal shift from a system purposed for domestic supply to one that responded to global demand.200 CRTC received more than 2,500 written submissions and more than 30,000 informal comments to its call for comments,201 so I assumed nothing would result from my intervention. In July, 2014, in an email that I nearly missed because it went into my junk file, I received one of 118 invitations to appear personally at the LTTV hearing to be held in Ottawa in September. There were a total of 118 invitees including 10 individuals, including me. The other 108 invitees represented every Canadian stakeholder organization: big and small networks; federal and provincial government entities; lobby organizations including CMPA, Writers Guild of Canada (WGC) and Directors Guild of Canada (DGC); as well as a few U.S. services with presence in Canada including Netflix and Google. I felt the invitation was an honour and still do. However, when I did the math and calculated that the invitation placed me in the 0.5% invited to testify (only counting the 2600 written submissions), I wondered “why me?” The answer would need to wait.

As I began to prepare, global attention on a Canadian TV series, Orphan Black (2013-2017, Space, BBC) caught my attention. The show had been created by a Canadian, produced by a Canadian company, developed by a Canadian TV network (CTV), and starred a Canadian actor. Nevertheless, its success was attributed to BBC in two headline articles in Variety. This suggested that even when the system did result in a show with market performance, Canada wasn’t taking or wasn’t given credit. My piece about the need to rebrand Canadian TV struck a nerve with the industry, and stayed on the top page of Playback’s online edition for days.202

On receiving the schedule for the CRTC hearing a few weeks later, I experienced a second surprise. I was scheduled to lead off Day 2, between stakeholders such as Google, CMF, Telefilm and the Competition Bureau on Day 1; Bell Canada and CMPA on Day 3; and Rogers Media on Day 4.203 The instructions stipulated that presenters would have ten minutes for a prepared presentation and would then be questioned by CRTC Commissioners for up to 40 minutes. I doubled down on my preparations.

On September 8, Day 1 of the hearing and the day before my testimony, I traveled to Ottawa to get a feel for the setup. CRTC Commissioners sat at the front of the room in a row at a long, elevated desk facing down on testifiers, audience, and press. About ten feet in front of them, two long tables, one in back of the other, with room for about 20 chairs faced the Commissioners; these were for the presenters’ teams. Behind them were chairs for the audience and press. I would be testifying entirely alone with the two presenters’ tables all to myself. The hearing kicked off with participants including Google, with their team of executives and lawyers. The Commissioners were extremely tough on Google. That night I called my Mom. Already memory challenged, Mom never lost her line to the truth. When I told her I was a bit nervous, she replied “Just look them right in the eye and pretend you are their best friend.” The next morning, in addition to the pile of sticky notes that I spread out on the table, I kept her words closest to me, printed in black sharpie. Thank you Mama, it went well.

My presentation, entitled Can Con to Can Brand—Let’s Pivot Our Goal from Domestic Supply to Global Demand was well received. Per the excerpt below, my message was that content is not king. Hit content is king:204

“Legendary TV exec Brandon Tartikoff said anything can be pitched in 10 seconds. Here’s mine: let’s pivot our goal from domestic supply to global demand. Let’s get in it to win it. By it, I mean the global competition for audience attention… Compelling TV dramas beat extreme odds to become hits: popular, therefore profitable. This leads to truth. Content is not king. Hit content is king. TV drama is so costly; popularity is its sole business model.”

I concluded my remarks by suggesting a five year goal be “a string of global hits.” My remarks were subsequently mentioned a number of times during the hearing. Chairperson Blais asked me to follow the hearing closely and submit a final report with my thoughts, to which I agreed. In October, I delivered a report to the CRTC entitled “Future- proofing Canada’s media system — from investment to return on investment: Global applause is not just good business, it’s great culture.”205

When I left the room I asked a CRTC staffer if they knew “why me?” to lead off Day 2? The answer was on background then, but I can share it now. Of the thousands of submissions, CRTC had found nearly nothing to work with. They expected strategies to embrace the future, but nearly all players were facing backwards, as observed by Professor Michael A. Geist, Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-commerce Law at the University of Ottawa, Faculty of Law:

“Let’s Talk TV lifted the curtain on what was happening globally and revealed that most of the legacy players were like: ‘Oh no, let me just hide under the regulations til I retire.’”

Only one other submission besides mine framed the disruption as a historic opportunity to seize the global marketplace. It was from eOne, one of Canada’s only vertically integrated companies (development, production, distribution) whose capacity included the studio function, meaning they financed productions in return for global distribution. However, eOne Television’s dynamic CEO John Morayniss was not scheduled to testify until Day 10. As one of Canada’s few globally exporting media companies, eOne advocating for global hits might be viewed as being in the company’s self-interest. As an academic, my presentation could be perceived as neutral. En route home later that day, I was asked to draft an article about my experience at the hearing. In The Globe and Mail, I argued that Canada should…

“Race to embrace the opportunity to enter the global battle for audience attention. With our talent, creativity and production excellence and no longer burdened by our too-small market – we should be world-beaters.”206

As the hearing played out, lobby organizations including CMPA, WGC, DGC, and ACTRA, advocated for the status quo and to extend existing regulatory instruments to global services such as Netflix. During a contentious discussion with the WGC on September 11, Chairperson Blais asked the WGC, given that they are writers, to tell an easily understood story of Canadian TV, asserting the issues were bewildering to the Canadian public who just wanted to watch their favourite TV shows and pay less for them. Before the WGC phalanx could come up with a logline, I tweeted out my take on the imperative transformation: protect and correct (Canada) to send and receive (world):”

“@irenesberkowitz #talktv @CRTCeng @WGCtweet JPB you asked story of CAN TV? How’s this: PROTECT CORRECT (20th cent market) to SEND RECEIVE (21st cent world)?!”

The story of LTTV would not be complete without the Netflix saga. On Friday, September 19, the hearing’s final day, Corie Wright, then Netflix head of public policy, was testifying. At that moment, I was in the BNN-TV green room, awaiting a live appearance. My message would be that Netflix was a huge opportunity for the industry — not a threat. Watching the hearing on the TV screen, I saw a conflict erupt about what data Netflix would provide to CRTC. But at that moment they called me; my conversation with BNN host Frances Horodelski went well. However, the argument at the hearing between Blais and Wright did not. It escalated then ended with a draw, with Netflix promising to respond after the hearing. A few weeks later, Netflix declined to provide proprietary viewership and subscription data to CRTC, on the grounds that CRTC could not guarantee confidentiality. In retaliation, CRTC struck Netflix’ entire presentation from CRTC’s record of the hearing. CRTC also struck Google’s intervention for the same reason, for failing to comply with the order to submit proprietary information. Today you get “no results” if you search for these interventions.207

Starting in November 2014, CRTC began to roll out eight decisions.208 The theme was bold and consistent, an argument in favour of opportunities in the global, online era. The tone was consistent with the historic New Media Exemption Order of May 1999, when CRTC had declined to regulate the Internet. The bottom line was that the regulator had decided to no longer protect Canadian business models from digital shift because they believed it was not in the public’s interest that they do so. In other words, protecting legacy business models was out. Protecting Canadian consumers was in.

For me, the LTTV decision of January 29 had a consequential inclusion on an issue central to Canadian TV, simultaneous substitution.209 Most in the industry still had little clue how this regulation works, much less its role as the financial underpinning of broadcasting and production. While most believed the long standing rhetoric that the system protected Canadians from the U.S., few in the industry knew their money depended on Canadians’ love for U.S. TV. But CRTC did know that a consequence of the shift to online viewing would be that the gift of simsub would stop giving. Canadian content would need a new funding model and the industry would need to invent it. So here’s another tidbit that has not been public until now. Back in July 2014, when I sent my pre-hearing answers to CRTC’s questions, my answer to the one about the future of sim sub was to suggest that an experiment be tried: prohibiting it on one high-profile program, Super Bowl. While most simultaneous substitution went unnoticed, CRTC often received complaints from Canadians who wanted to watch the U.S. Super Bowl commercials, so this case would focus on the actual content being substituted, i.e. the advertisements, not the programs. I’ll never know whether CRTC agreed with me or already had the same idea. But here’s what happened: CRTC floated a deadline to end sim sub on Super Bowl. There was immediate push back from CTV, even though Super Bowl simultaneous substitution comprised a minuscule percentage of what CTV’s own submission to Let’s Talk TV asserted were “millions and millions” of hours substituted each year.210 CTV fought to continue substituting Super Bowl on the basis that it had purchased broadcast rights based on the expected audience size that included the 30% bump — a completely valid argument. Eventually, the legal battle extended to the Supreme Court, where CTV prevailed on December 19, 2019, and even to Trump’s United States Mexico Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA) that went into effect in July 2020. Upon reflection, was Super Bowl gate a teaching moment about the need for a new funding model? Maybe not so much. Perhaps it was too theoretical.

On March 12, 2015, with a speech by Chairperson Blais, CRTC released another LTTV decision, the one of most significance to premium TV:

“Some people will tell you, as they did at our public hearing last fall, that everything is fine and there is no need for sweeping change. I’m here today to tell you that this model will not work anymore.”211

Blais’ announced that content rules would be relaxed as part of a commitment to “tearing down barriers to innovation that have hampered broadcasters and producers.” Aligned with my suggestion to simplify Canadian content, he asserted:

“As long as the story is told by a Canadian, let’s get the best talent working on it and make something that will conquer the world. Forget about the ‘made in Canada.’ We want content that is made BY Canada.”212

I was rushing to teach MBA’s when my colleague Emilia Zboralska shouted: “Wait – you made history.” She had been reading the decision and saw that I was named in two paragraphs:213

“55. Both Irene Berkowitz of Ryerson University and Entertainment One (eOne) discussed the importance of rebranding Canada as an exporter of global hits, to make Canada’s brand known as a creative brand. In their view, Canada is currently known primarily as a country with strong production crews and good financial incentives, but with no track record of producing real global hits.”

The second mention noted my solution to brain drain, arguing that it could be converted to a brain chain for ultimate brain gain:

“108. Similarly, Ms. Berkowitz discussed turning Canada’s proximity to the U.S. into a competitive advantage rather than disadvantage by changing the points system so that Canadians do not have to be residing in Canada. ‘Canadian-created stories,’ in Berkowitz’s view, would recapture the value of Canadian expatriates working in Hollywood and make the ‘brain drain’ into a ‘brain chain.’ She proposed a new points system which can be found in her written submission.”

These mentions ignited fresh interest in my perspective in the media, including The Globe and Mail:

“If, as CRTC chairman Jean-Pierre Blais aptly observed, ‘content is king’ and ‘viewer is Emperor’ – isn’t hit content God? … Television programming is all about quality and popularity. It’s never been otherwise, since the days of I Love Lucy, back in 1951. Just ask our Canadian broadcasters; they’ve been monetizing Hollywood hit content since then.”214

A related question to “why me” at the hearing was now “why me in the decision?” Months later I was told why. Similar to the lead-up to the hearing, the two-week hearing had produced little forward-facing material. CRTC’s mission to ignite policy innovation had not gone exceptionally well. The breach opened by the Netflix fiasco became a rabbit hole and most of the industry jumped in. CMPA issued a statement saying they were “stunned” by the CRTC’s statement that it would no longer protect producers in their negotiations with broadcasters over intellectual property. Producers didn’t then, and don’t now, believe in their own strength, perhaps a result of decades of being considered weak.

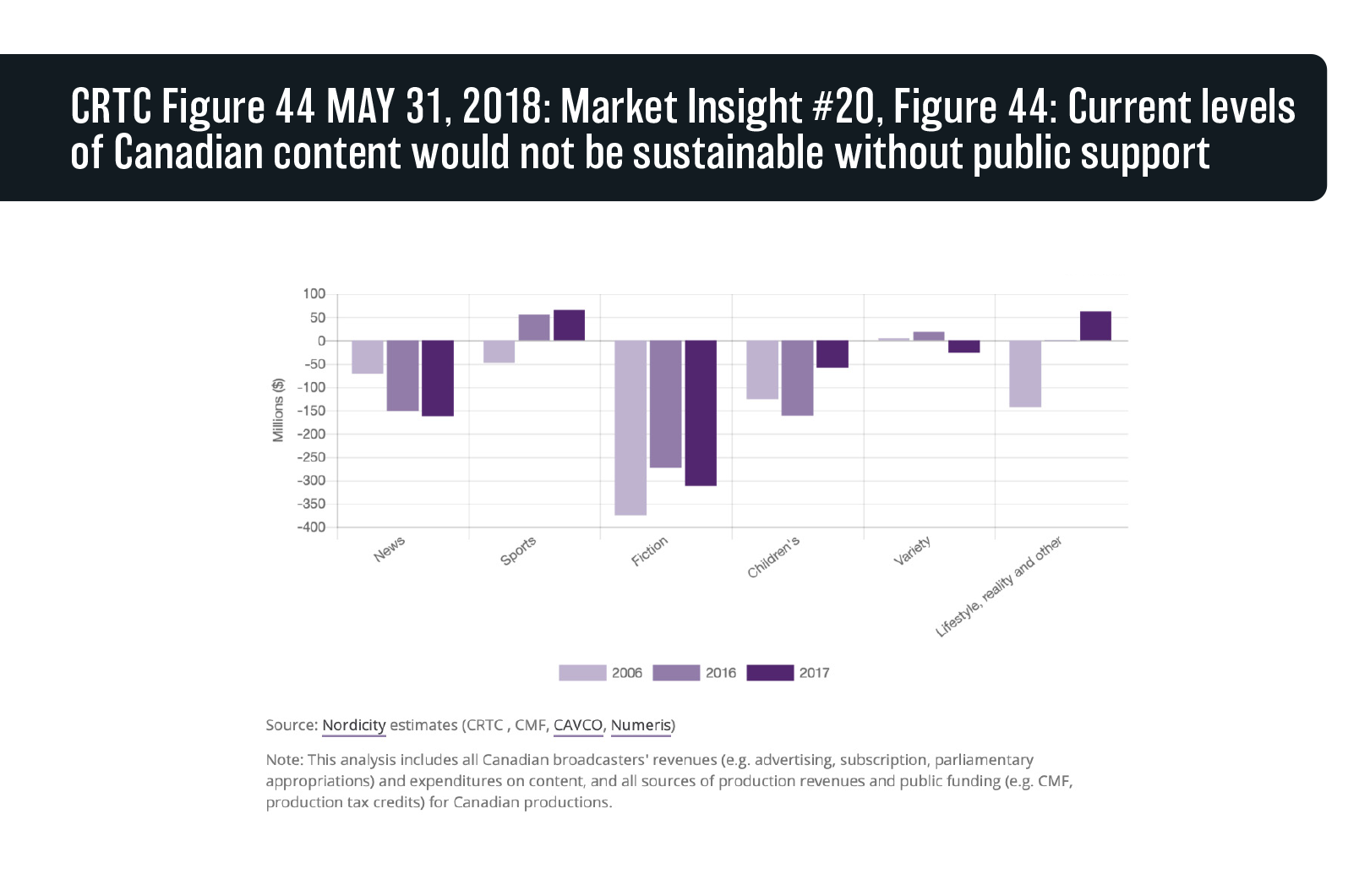

By the end of March 2015, CRTC seemed to have completed a pivot from protecting Canadian viewers from the TV they love to a more authentic mission to protect Canadians’ safety online. They summarized “past to future” in a fun infographic.215 In the future, driverless cars would transform our “waze” of life. Canadian TV would win global audiences, per the “Create” vertical with content that would compete on the world stage, on the new platforms, in a system that would remove barriers to innovation.

As for the fireworks with Netflix, I have no proof, but have come to believe they were mostly for show. My suspicion is that CRTC knew the hearing was crumbling and that the industry perceived media disruption to be a dire threat to the status quo. even though The Act required the system to be technologically current. I suspect CRTC had no better choice regarding Netflix, lest they appear to be abandoning the national industry that had always complied so willingly with their policies — just at the moment of total upheaval.

In addition to CRTC, other top policymakers had a clear sense of the ongoing changes and what they would mean for Canadian TV policy. For Valerie Creighton, President and CEO of Canada Media Fund, LTTV could have gone further towards acknowledging the impact of the ongoing disruption of linear broadcasters, Canadian content’s financial gatekeepers:

“For us, what was left out [of LTTV] was the concept of the Canadian broadcasting system as a full trigger for Canadian content… Maybe it was premature to have that discussion at that time or maybe there wasn’t a willingness, but that was the biggest issue for us and it was left out entirely.”

Karen Thornstone, President and CEO of Ontario Creates, emphasized the need for a policy goal that would chart a path towards seizing the new opportunities in the global market:

“Let’s Talk TV was addressing symptoms and not underlying issues. I don’t think it moved us anywhere in the big scheme of things. We were moving chess pieces around, but we didn’t even begin to tackle how to finance content in the global universe, what support content creators need to make market-worthy high-quality content? There’s a huge disconnect right there.”

In retrospect, CRTC’s approach seems aligned with the analyses of Michael E. Porter, which argue that a well-established policy framework can be its own worst enemy in times of disruption, so government must lead:

“Policy entitlements… are an invisible dry rot that slowly undermines competitive advantage by slowing the pace of innovation and dynamism… Government’s proper role is to push and challenge industry to advance, not provide ‘help’ so industry can avoid it… Successful national industries often gain some political power, and the temptation is great to exercise it… There is also a natural and sometimes fatal tendency for successive generations of managers to want to eliminate “excessive” competition in order to make life more predictable.”216

From the hindsight of 2020, others besides myself would look back at LTTV as the government’s best attempt, of what would be four ups at bat to embrace the future. Here’s LTTV, according to Michael Geist:

“In the period leading up to Blais – we’re pretty much all insider baseball. There was a prevailing sense of a captured regulator, who saw themselves as defending the interest of select stakeholders. You’ve had this game where the broadcasters sort of playing along, pushing the envelope as much as they could to limit their contributions or the scope of regulation, but ultimately knowing in a closed system they were the beneficiaries of that closed system. And of course, missing from all of that was any sense that this was an actual market place, much less that consumer perspectives mattered at all. Even as [Blais] was saying, hey this is your chance to succeed, the response was as close as you could get to ‘We don’t really care if we succeed, we care about getting paid. And we’ll worry about [that] after you find a way to ensure that we continue to get the kind of handouts we’ve always gotten.’”

As LTTV faded from the news cycle, it remained to be seen whether the LTTV thought-leadership take hold and if so, what policy changes would occur? Or would the future of Canadian TV be found in the rear-view mirror?

2016-2017/Creative Canada Policy Framework

Canadian Netflix subscriptions continued to leap, from 4.1 million in June 2015, to 4.7 million by December, and 5.2 million by April 2016. Nearly half of the 11.5 subscribers to cable reportedly considered cancelling their cable subscriptions.217 However, while data suggested that digital services were additive and broadcasting economics were not dire, industry ire grew louder. Consumer cable subscriptions had even grown slightly from 2010-2017, from 10 to 10.5M despite a saturated, mature market and the hype about cord cutters and cord nevers.218 A ten year review of media advertising in Canada supported the analysis that linear TV revenue was hanging in. Overall growth in advertising grew 16% from 2008-2016 but during this decade, broadcast TV advertising decreased by only about 1.4%.219

A few months after LTTV a new political era had begun. On October 9, 2015, Justin Trudeau led the Liberal party to victory and became Prime Minister, ending the nine year term of Conservative Stephen Harper. Trudeau appointed a new Minister of the Department of Canadian Heritage (DCH), 39 year old Melanie Joly. On September 13, 2016, Joly announced an initiative to examine the impact of digital disruption, highlighting her own millennial perspective. Canadian Content in a Digital World, also known by its Twitter handle, #DigiCanCon, ultimately became the Creative Canada Policy Framework.220 As in LTTV, there was a call for comments. Canadians were invited to submit thoughts on “how to strengthen the creation, discovery and export of Canadian content in a digital world.”221 Hadn’t this just been done by CRTC? #DigiCanCon began with a cross-country consultation by an Expert Panel. The resultant report222 was too bland to warrant much press; my editor at The Globe and Mail agreed. While the DCH report was in process, in June 2017, JP Blais, whose 5 year term as CRTC Chair was ending, made his final speech at the Banff TV Festival, warning that if the industry failed to wake up, it would find itself on a “death march.”223

I had recently returned from Singularity University in Silicon Valley, armed with a top-down, global view of digital disruption. There’s a saying in the Valley that any organization designed for the 20th century will not survive in the 21st.224 I was more concerned than ever about Canada’s seeming inability to adapt TV policy to the 21st century disruptions and moreover, what this could portend for public policy in all the disrupted sectors. A piece in The Globe and Mail Report on Business that I wrote on this issue got more views than an adjacent one about newly elected President Donald Trump:

“Digital distribution, by vanquishing national boundaries, has eliminated the entire purpose of Canada’s TV policy framework: to compensate for a small national audience. The upside? Global attention is now ours to capture… Why tie the fate of Canadian creators… to broadcasters who make content only as a licence obligation and don’t care about winning the battle for attention? Our risk-taking content makers deserve updated policies… For linear broadcast and cable, it may be the worst of times. For content makers, it could be the best ever.”225

The release of the final report by the Joly panel was scheduled for September 29, 2017. As Policy Fellow in the Ryerson University Faculty of Communication and Design (FCAD), I was invited to attend this packed event, hosted by Economic Club of Canada at the Fairmont Chateau Laurier in Ottawa. Joly introduced new CRTC Chair, Ian Scott and launched the initiative, Creative Canada Policy Framework. At 38 pages, the document was refreshingly brief; I thought back to the 14 page Aird Report of 1929. Creative Canada featured big themes that were infused with a Silicon Valley ethos. To prepare, Joly had traveled to California to meet with the top media companies such as Google, Facebook and Netflix. While it was not widely known what happened in the meetings, I’d heard unofficially that Joly had requested changes to algorithms on behalf of Canada and that her request to impact their core IP was, unsurprisingly, refused. Nevertheless, Creative Canada embraced the spirit of working with — not against — the flow of the global media market. I was reminded of Chris Anderson’s analysis that this very strategy — being aligned with, not against the flow of the Internet — had been key to Google’s early success.226

Creative Canada’s first principle was to assert the fundamental role of safe, affordable, access to 21st century oxygen, a.k.a. an open Internet. It then set out a series of media initiatives that each targeted a pain point in the national framework as it crashed against global disruption. It advocated that media should become an economic driver for the Creative Industries, said to comprise 3% of Canada’s GDP and assessed as larger than the insurance and forest industries combined. The new policy framework identified exporting CanCon as a priority. It established the Creative Export Strategy227 to “maximize the export potential of the creative industries” and created an export funding program of $7M per year to facilitate the relationships needed to make the business deals, an announcement that was met with applause.228 There was also applause for the announcement of a temporary top-up to the DCH contribution to CMF, because cable subscriptions would continue to drop until new policies could be designed. Also announced was a larger initiative that would be jointly undertaken with the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Economic Development, under then Minister, Navdeep Bains. It was called the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review (BTLR) and would consider the fate of Canada’s two main acts governing communications.

During the speech, my optimism grew. Would Creative Canada turn Canadian policy towards thrilling opportunities in the online era? Spoiler alert: it didn’t turn out like that, particularly for Minister Joly. Her troubles started moments later in that very room with the most high-profile announcement that Joly had clearly saved for her finale: the Netflix deal.

Netflix was already investing significantly in production in Canada — so much so that they had concluded it was in their interest to formally establish a production presence, i.e. a virtual studio. As a foreign investment in the cultural sector, this had required approval by the Minister of Heritage under the Canada Investment Act (ICA). Discussions led to an agreement that would establish a Netflix production presence with a commitment to invest 500 million dollars, over five years, in content produced in Canada. Netflix was already investing in certified Canadian content in the only way they could: In partnership with Canadian producers and broadcasters. However, the ICA agreement did not address Canadian content. This would become a contentious issue.

You might think that Netflix’ first production studio outside the U.S., with a deal approved under ICA, would be seen as an endorsement of the world-class excellence of Canadian production crews and met with applause. You would be wrong. As the speech ended I scanned the room; many seemed stunned. I haven’t shared publicly that I was first to leap to my feet for a standing ovation. Reluctantly, my table followed, then the room. From that afternoon on, Netflix became the raw edge of rage towards global media transformation and Joly its cynosure.

Nearly all the press was negative, including in The Globe and Mail. But they did print my piece too: “Five Reasons to like Heritage Minister Melanie Joly’s Netflix deal:”

“It’s not easy to turn a supertanker, particularly when that ship is a massive public policy framework that has been entrenched, and working rather brilliantly, for most of its five decades of existence. There is a natural tendency for industry to try to turn the ship back towards a cozy past, which no longer exists. The boat spins, swirling to disaster. In launching #CreativeCanada, the Hon. Minister of Canadian Heritage, Melanie Joly has turned the Canadian media policy supertanker, and set it sailing towards thrilling opportunities in the online era.”229

Had Canadian TV perceived itself a victim for so long that it could not see that it had been crowned a winner? In the piece, I laid out five strengths of the deal:

- Competition makes everyone better. Netflix’ need to succeed could only help Canadian content makers up their popularity game.

- Competition makes everyone richer. If Canadian content got more popular, there would be more ad dollars in the system.

- Exports make everyone richer. Netflix only develops content they believe will work in the global marketplace. This could help CMF improve its 2% ROI.

- Popular content increases production volume. The deal would further enrich the production workforce and infrastructure.

- Carrots, not sticks are essential policy instruments in the global era. Protective instruments such as quotas won’t work. Incentivizing players to compete in the global marketplace is strong policymaking.

Len St-Aubin describes how the new dynamics landed:

“It would take a change of mindset for many in Canada’s production sector to understand they could seize the opportunities. To that end, Netflix committed to holding pitch days for Canadian producers. One notable outcome was Netflix’ first Québécois film, Jusqu’au déclin (The Decline), a project that had been rejected by the Quebec industry and funding agencies. It became a global hit. Ironically, despite its Québécois creative team, cast, crew, location, facilities, and even English-language dubbing, the film could not be certified as Canadian content because it was fully financed by a foreign entity.”

Details were MIA regarding the implementation of Creative Canada’s grand themes, so I began to think about what policy innovations would be needed to actualize its goals. Playback published my argument for a producer-accessed, platform-agnostic, sliding-scale bonus system that would do no harm to production strength:

“We don’t (yet) have a policy instrument to incentivize content that can win the battle for global attention… Our producers have evolved to become, arguably, the strongest pillar in our content ecosystem. To seize forward-going opportunities like Netflix Canada, don’t they need direct access to funds in a platform-agnostic point system?230

I continued to refine the idea. The result is Globality Score (G-Score), detailed in Chapter 7 as part of my plan to incentivize global TV hits.

Fury over Joly’s Netflix deal spread, muting any possibility of a coordinated focus on implementing Creative Canada Policy Framework. It morphed into an uproar over a so-called Netflix tax. Netflix had become the nominal scapegoat for disruption panic. It was called a foreign giant, even though with its expenses for global scale and must-see content, Netflix was not yet profitable. I suspected a component of the anger lay in the love/hate complexity between Canada and the U.S., a sort of jealousy. Nothing had prevented a Canadian entrepreneur from inventing Netflix.

With hysteria driving the discussion, the phrase Netflix tax had become an epithet for several completely different revenue instruments. I began to report out a piece that separated fact from fiction, speaking with Canada Revenue Agency, Department of Canadian Heritage, Department of Finance Canada, Finances Quebec, and Netflix. As I was finishing the piece, Playback called with a request to publish immediately because the Quebec industry had signed a petition calling for the government to require “foreign giants” to pay sales tax, which made little sense since consumers pay sales tax. Playback deemed my explainer so important they immediately released it from behind their paywall.231 I pointed out that Netflix was already collecting sales tax in numerous jurisdictions, and had no issues doing so. However, I also noted that a separate negotiation would be required to cross-subsidize sales tax proceeds to support the TV industry. Also conflated were the production and subscription functions. The new Canadian Netflix production activity would spend money but would have zero revenue. It was separate from the SVOD operation, whereby subscriptions are remitted to U.S. corporate headquarters. A Netflix tax had also been conflated with the concept of a revenue levy, a subsidy similar to Canadian cable distributors’ contribution through CMF. A key problem with that concept was that permission for Canada to levy a foreign company would require new legislation.

A Netflix sales tax did come into effect in Quebec on January 1, 2018. Its implementation was “spectacularly successful,”232 but not to the benefit of the Quebec TV industry. 38 million dollars raised by August 2018 went towards the province’s general revenue fund, slated for projects including education, infrastructure or security. (From the 2021 pandemic perspective, general priorities seem even more critical.) A year later, in January 2019, Saskatchewan joined Quebec233 in implementing a sales tax on foreign digital services. (Spoiler alert: in 2021, a federal sales tax on digital services was informally announced.) Some of my published predictions came true. Netflix outspent its financial promises. By the January 2020 release of the report from the fourth inquiry, the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review, Canada’s production sector was at record employment and was even training disrupted workers from other manufacturing sectors for jobs in TV and film.

But back in 2017, the Netflix hysteria continued to take its toll on the office of the Heritage Minister. Joly stumbled repeatedly trying to justify her Policy Framework. Ironically, this was most true in her home province, Quebec, which had been accustomed to special treatment since the beginning of the TV policy regime, even though French-language TV performed remarkably well in Quebec, attracting up to 70% of the audience. On July 18, 2018 Joly was moved out of her post and appointed Minister of Tourism. Pablo Rodriguez became Minister of Canadian Heritage. In a subsequent cabinet shuffle about a year later, on November 20, 2019 Rodriguez was appointed Leader of the Government in the House of Commons and Steven Guilbeault became Minister of Canadian Heritage. In that shuffle, Joly was moved to Minister of Economic Development and Official Languages. Thus far, all three of Trudeau’s Ministers of Canadian Heritage have been from Quebec.

What were key takeaways from Creative Canada? An Expert Panel member positioned it as an attempt to wake up the industry to the global market:

“Creative Canada was basically trying to say, let’s just change the script. And that’s scary, right? It’s scary to those who are part of yesterday. But it’s not a birthright to make money off the government to create stuff… Wouldn’t it be great to do great storytelling in Canada because and by the way it’s going to make money for the industry. It’s going to create jobs. The existing regulatory systems are flawed and they need to be nimble, not driven by just protecting the legacy institutions. That’s all Creative Canada was trying to do.”

Policy CEOs applauded strength in acknowledging that the media market had become global:

“The top up the government decided to make was in the right direction until the review of the Broadcast and Telecom was announced. The objectives of Creative Canada are good, our early stage development leading to better exports, but we were really not sure what the practical outcome would be… There was a big fury in the French community over the whole Netflix thing, but unless somebody is prepared to really step up and set up a Canadian Netflix, the FANG group are the distribution models of the future.”

Valerie Creighton assessed Creative Canada‘s shortcomings in the context of an overall assessment of the global dynamics of the TV market, underscoring that audiences everywhere are more similar than different: they respond to good stories, well told:

“Canadians are citizens of the world and content that resonates with them can resonate internationally… that’s been demonstrated over and over again. If the story is great, good content will resonate around the world. If we’ve made a mistake in the Canadian system, it’s believing that’s not true.”

For Karen Thornstone, the weakness in this second inquiry was that it didn’t move things ahead fast enough. It was “much ado about nothing” for a one reason: it failed to tackle how Canadian creators would be successful in the global marketplace (my bold):

“Creative Canada was much ado about nothing. Setting aside the question about whether or not you tax Netflix, I personally believe those entities that are using and distributing content from any given country should be contributing to the system. Whether or not that’s a tax in the traditional way or not, I don’t know the answer to that. We keep trying to impose these outdated notions on modern industry mechanisms. If Creative Canada did nothing else, it needed to reflect the new market reality, the different participants in the system, and the global nature of the system. I don’t think it accomplished any of those things. It gave some lip service to acknowledging things were changing and tacked on a few little cute things like a Netflix promise to spend some money here, but it didn’t take us any further. If Canadian content creators are going to be successful, they have to do that in the international marketplace. Any policy that doesn’t tackle that issue isn’t going to move us where we need to go.”

As widely observed, politics impacted the outcome of Creative Canada, per this assessment by CMPA CEO Reynolds Mastin:

“I felt for her [Melanie Joly] because the explosion in Quebec was so ginormous. She was trying to find her political feet as a minister and a politician. With another year under her belt, it might have been a different story. People forget she secured millions of additional dollars for the Canada Media Fund to fill the funding gap left by declining contributions from cable companies. You only have to look at how successful she’s been in her subsequent portfolios as Minister of Tourism, Regional Economic Development and Official Languages, to see that she has considerable political acumen, resilience and an ability to get things done.”

In the end, politics obscured the value of the Creative Canada Policy Framework, as observed by Professor Michael Geist:

“DigiCanCon was clearly political. The whole Netflix tax issue is a really unfortunate example of how a single term was captured and taken to mean a myriad of different things. The result was masked as political messaging instead of developing any sort of reasonable policy.”

Like Let’s Talk TV, Creative Canada joined a pile of policy tomes as more tinder for the ring of fire closing in on the outdated framework.

2018-2019/Harnessing Change

On October 12, 2017 CRTC issued a public call for comments on a media inquiry. Surprise, surprise. This go around would examine “future programming distribution models.”234 A November 24 deadline for public comments was extended twice, to December 1 then to February 13, 2018. Would the third time be the charm? Or would there be fatigue for a third proceeding, in as many years, into the impact of digital disruption?

On December 7, CRTC released Consultation of the future of program distribution in Canada,235 asserting it wasn’t a report but a reference document. It seemed an attempt to insert data into a discussion that had been low on facts and perhaps trigger some enthusiasm for the third examination of the impact of the online era in as many years. Six chapters in the reference document described the impact of digital shift including consumer uptake and shifting revenues, presenting the usual data points.

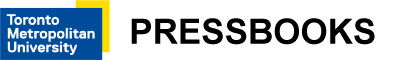

However, when I came upon an analysis of Canadian content, labelled Chart 26, I was surprised. As shown, Chart 26 was a “what if” thought experiment that estimated future profit or loss absent all forms of direct public support for various genres of Canadian content, noting that it did not include indirect support such as cross-subsidization by tactics such as simultaneous substitution. It showed clearly that English-language Canadian drama, the most subsidized genre, also sustains the largest loss, about $300M per year — but I knew that. What surprised me was the analysis of this data point, that this chart proved the sector could not exist without public support! As a researcher, I would have interpreted the same data differently. Taking into account that high-budget TV is the most popular and profitable genre on the planet, the data in Chart 26 suggested to me that something is very amiss with the policy framework. To me, the chart showed that policy wasn’t building a self-sustaining sector — given that global market success was now there for the taking.

On May 31, 2018, CRTC released their final report, Harnessing Change: The future of program distribution in Canada.236 To me, a sad feature was the title. Harnessing Change suggested containment of the old ways rather than a strategy to seize historic opportunities.

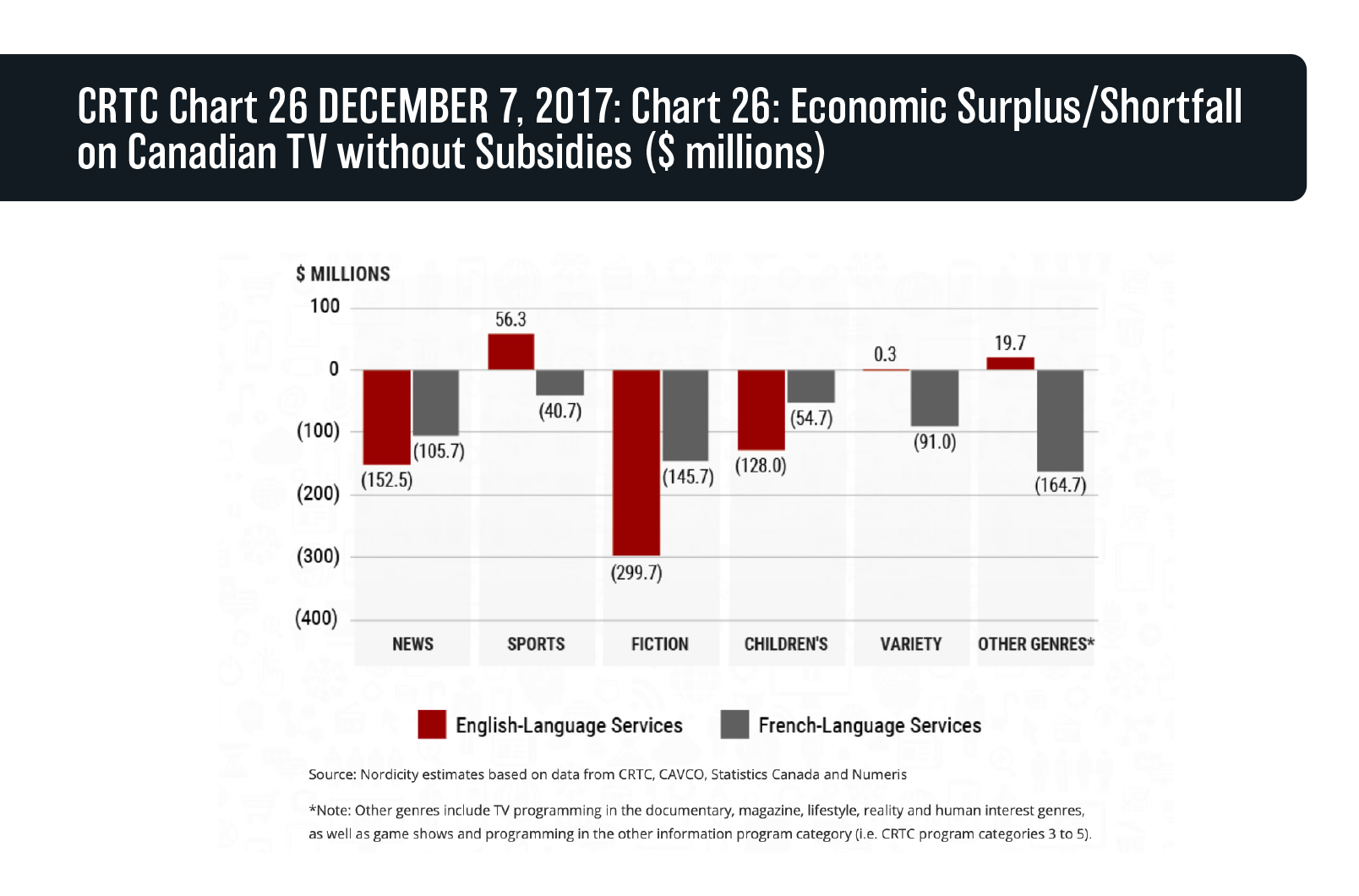

My main takeaway was that Harnessing Change doubled down on the error from the December reference document. My eyes fixated on a graph extremely similar to Chart #26 with the difference that it was now called Figure 44 and tracked three years of revenue to Canadian content with a new title: “Market Insight #20, Figure 44: Current levels of Canadian content would not be sustainable without public support.” “Market Insight #20” was boldly titled with the conclusion from Chart 26: English language drama could not survive without subsidies. To a researcher, this “insight” exemplified two common cognitive biases in data analysis: sunk costs and confirmation bias. Sunk costs means having so much money invested in doing things a certain way that it is impossible to change course even if the status quo is not effective. Confirmation bias is the psychological complement to sunk costs. It’s the cognitive tendency to interpret evidence to confirm pre-existing conclusions, to discount alternative interpretations, and to defend established paths. Playback invited me to publish my observations and reprinted both charts.237 In this piece, I argued that it should not be an acceptable policy outcome for billions of subsidy dollars to have no impact on the financial sustainability of Canadian TV! Global demand for this genre has never been higher. To me, the data in Chart 26 and in Figure 44 suggested an urgent need for a new framework with a new metric to award funding on the basis of globality.

Policy leaders were split on Harnessing Change, ranging from “very proactive and positive“ to the “poorest case of public policy making:”

“It was very proactive and very positive … recognized for the first time on paper that as people are cutting off their cable they’re often watching the same content over the top so the Internet and mobile devices are broadcast too. As a country we need to embrace that. Maybe in the short term we could move to a right of first refusal kind of process, where if a Canadian producer has a piece of Canadian content and it’s ten out of ten and they’ve shopped it to every broadcaster in the country and there’s no pick-up, why should we lose that idea? So if they’ve got BBC or Netflix in the financing structure, and they can demonstrate a way to ensure it will get to Canadian audiences, you know, maybe they should be able to trigger the CMF. The report lays the groundwork for some really good debate and analysis as they move forward to the review of the Act.”

Michael Geist weighed in on the Harnessing Change process, analysed to lack purpose, and as well the results, which amounted to facing backwards:

“Harnessing Change was the worst, the poorest case of public policy making on these issues that I can remember. I don’t think they made a compelling case for what they were trying to do and it was a dramatic U-turn from where they’ve been… In the end Harnessing Change was a revision to where they were pre Let’s Talk TV, almost like where things would have gone had Blais not been around. There was a clear resurgence of ideas that never go away, a continual attempt to resurface and bring back the same things again and again and again”.

Harnessing Change did seem a turn backwards from the visions of Creative Canada and Let’s Talk TV. A regulatory capture seemed possible because in its wake, stakeholders became emboldened in a mission to harness change. In January 2019, the mission went public.

On January 31, 2019, I was in an audience of more than 600 industry professionals at CMPA’s annual conference in Ottawa, Prime Time 2019. A main-stage panel, “Beyond Disruption: Crafting a Framework for the Future of the Industry,” included the CMPA CEO; Netflix’ Canada Head of Public Policy; as well as heads of Bell Media, Corus Entertainment, and CBC. The panel was moderated by the Chair of the BTLR panel, whose recommendations were set to be tabled a year later, in January 2020.

Following Netflix’ statement that it had committed hundreds of millions to production in Canada and was on track to exceed their promise of $500 million annually, CBC interrupted. CBC accused Netflix of being a “cultural imperialist.240 CBC subsequently doubled down with a tweet, saying “we are at the beginning of a new empire. Let’s be mindful when responding to global companies coming to Canada.”241

Shock rippled through the audience in response to the CBC remarks. A panelist asked: “How do we respond to international players whose primary instinct is to monetize a global audience?” Netflix calmly asserted that no media company has a monopoly on authentic Canadian stories. Facts supported the point. In 2017 Hulu had premiered the hit A Handmaid’s Tale (2017—) based on the book by Canadian Margaret Atwood. A 2017 Netflix/CBC co-produced series, Anne with an E, was based on the iconic Canadian book series, L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables. Yes; this source material was developed precisely because Netflix had the instinct to to monetize a global audience! CBC presumably knew this because in the same year CBC had partnered with Netflix and Halfire Entertainment on a limited series based on another Atwood book, Alias Grace.

My perspective is that CBC made four errors on that panel:

- comparing Netflix to an occupation that resulted in millions of deaths;

- not understanding the imperative for CBC to become outward looking and that the proper goal of a modern media organization is to monetize a global audience;

- not understanding that a fundamental of great storytelling is that hyper-locality is what resonates with a global audience;

- not understanding that popularity is the one sure sign of media success.

Cooler heads did not prevail. The panel ended on an angry note, with the panel agreeing that Netflix should be required to contribute to CMF. Netflix was told “We’re coming to get you” or something close. My analysis is that the whole altercation may have been a dog whistle to the moderator, who’s team was working on the BTLR report. When the BTLR report was released a year later, it appeared that the panel got the message.

Harnessing Change, like Creative Canada and Let’s Talk TV, faded away without meaningful results. To continue the baseball metaphor — was it three strikes you’re out?

2020/Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review (BTLR)

By the end of 2019, Disney+ had launched in Canada; Amazon Prime was growing; and Apple TV+ was coming soon. The streaming wars were full on. So was the mediaucracy. The task, as set out for the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review (BTLR) was to make recommendations that would “update and modernize” the Acts for the digital era. Of course, an expert panel had been assembled. In addition to Janet Yale, retired President of the Canadian Table TV Association and CRTC lawyer, the panel included the former President and CEO of Société de développement des entreprises culturelles (SODEC), a Quebec provincial funding organization, and five communications lawyers:242 As traditional, a first step was to request public participation, touted as “the heart of the consultations process.” This part kicked off September 25, 2018, sounding very much like prose from the 1929 Aird Report:

“[We] look forward to receiving submissions from a large and varied number of voices and from all corners of the country. The Panel’s consultation process will also include participating in a number of industry and academic conferences and meeting with a cross-section of experts, creators, stakeholders and other interested parties, including those from Indigenous and official-language minority communities.”243

The panel asserted transparency: “These written submissions will be publicly available after the deadline for submission on November 30, 2018.“ This did not turn out to be quite true. The panel appeared to be somewhat secretive, selective, and strategic with submissions that it made public. Well after the November 2018 deadline, some submissions were MIA, such as Netflix’ and Google’s. With data about new media contributions to the system missing from the public record, these companies released their submissions independently.

On June 26, 2019 the panel’s interim report was released, titled What we heard.244 Per the usual process, the panel reported that it had met with 150 individuals and groups in 11 communities across the country and attended 12 conferences. The timing, just before the July 1 weekend, seemed perfect to be ignored. Except for a political tweetstorm. The day after publication a tweet from the office of Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez implied that a political agenda seemed in play, that policy conclusions were a fait accompli and the government was “ready to legislate:”

“Pablo Rodriguez @pablorodriguez Thanks to @JanetYale1 & panel for their work. We will be ready to legislate once we receive their recommendations. Everyone has to contribute to our culture. That’s why we’ll require web giants to create Canadian content + promote it on their platforms.”245

The next day, in a widely circulated email published by the Wire Report, Heritage press secretary Simon Ross “doubled down”246 on the appearance of pre-existing conclusions, saying “It’s 2019, enough of the two-tier system…We need rules that are fair for everybody. If you participate in our culture, you have to contribute to our culture, end of the story. We will make web giants contribute to the creation of Canadian content…” Given that it was six months before recommendations were set to be announced, this mini-controversy proved more interesting than What We Heard. The report was vague and devoid of specifics or insights about the field consultations. As a researcher, I’m aware that a challenge of field research is to tell a story with qualitative data. If there was a story to report on the field consultations, it did not seem well told. The report featured phrases like “a number of parties” which begged questions such as “who” and “how many?” Nor was there a full list of submissions with links, an omission eventually corrected. Like the Creative Canada interim report before it, the BTLR’s What We Heard received little attention.

With the final BTLR report on the horizon, I addressed what I considered to be a fundamental media policy question, one I hoped would figure into the deliberations on updating TV policy. My Playback article was called “Bordering the U.S.: Win or lose for Canadian media?”247 Using historical examples, I observed that all Canadian electronic media policy had been a response to perceived domination by the U.S. and illuminated the love/hate paradox that ran through Canada’s 20th century media policy. I pointed to YouTube as a powerful contemporary case that proves living next to the U.S. is a win because Canadian producers use U.S. audiences to monetize Canadian YouTube, using a straightforward media monetization model — popularity. I followed it up with a second piece detailing the accomplishments of Canadian YouTube producers. This piece followed their money,249 setting out their remarkable accomplishments in an ungated, global ecosystem. Without policy quotas or protective regulation, Canadian YouTube creators exploited the superpower of building an audience.

As January 2020 approached, one sign of high anticipation was a federal cabinet shuffle that may have been a result of Rodriguez’ tweetgate, perhaps intended to distance the government from allegations of a preconceived policy deal. On November 20, 2019, Rodriguez was replaced with Steven Guilbeault as the new Minister of Canadian Heritage and Rodriguez was moved to Leader of the Government in the House of Commons.

Days before the release of the BTLR report, I published an interview that contained a stark warning, by industry icon Charles Falzon, about the stakes in not aligning with the unstoppable global forces (my bold):250

“The question is: what do we have to build on? We have a lot of great assets, great production crews and great individual talent. But our whole approach has been for the most part, myopic and protectionist. Suddenly we’re not prepared. We’re not prepared with government policies that are relevant, or an economic model that is international in scope. I accept that we need incentives and support. Our system must be interlinked with a global content marketplace. We have a lot of catching up to do. Let’s get in the driver’s seat and be players rather than be in denial. Can we find opportunity in the global media ecosystem? We certainly can and many are, despite the system. What we said in 1969 or ‘79 or ‘89 about protecting Canadian identity through protectionism arguably didn’t work then. It certainly will not work now… Unless we drop the antiquated nationalism, we’ll be left with nothing.”251

The BTLR report, also known as the Yale report, was titled Canada’s communications future: Time to act.252 It dropped Wednesday, January 29, 2020. Its 235 pages included 97 recommendations. Response ranged from enthusiastic to excoriating.253

CMPA, per CEO Reynolds Mastin, endorsed long-held 20th century policy principles and acknowledged the urgency for some type of response to historic changes:

“Our organizations were supportive of the key principles, most importantly the long-standing one that those who benefit should contribute… While there are multiple benefits from having an increasing footprint in this country, particularly jobs and economic activity, there needs to be balance between service production and domestic production, which have always been two pillars of the sector… If the expectation is to have everyone on board for everything, you will do nothing because in the meantime, the world is changing.”

Critics (including me) perceived that the BTLR strategy was a fundamentally flawed response to the global disruptions. Recommendations #55, #56, and #64 suggested CRTC’s powers be expanded to register and regulate the whole of the Internet. Appearing to overturn decades of promises to Canadians for an open, neutral Internet, it was criticized as being based on a “demonstrably false premise” and even possessed of “bureaucratic hubris.”

Critics included former CRTC Telecommunications VP, Peter Menzies, who, in 2016, had asserted that Canada could “no longer define ourselves as gatekeepers in a world in which there may be no gates” and had set a CRTC goal to “help Canadian creators take advantage of the opportunities in the new global environment:”

“The concept of a free, unfettered internet through which Canadians can speak, learn and communicate without permission of the state was blown apart this week by a series of invasive and unjustifiable recommendations… the panel opted instead for making the internet and all of its subscribers pay – with their wallets and their freedom – to support the selfish demands of a small, unsettled segment within an otherwise flourishing and entrepreneurial creative industry.”254

Michael Geist captured the paternalistic ethos of Canada’s TV system in his January 30 post entitled, “CRTC knows best.” He argued that the BTLR recommendations be “firmly rejected” by the government, quintessentially as “unnecessary to support a thriving cultural sector and inconsistent with a government committed to innovation and freedom of expression.”

Hollywood Reporter observed that the BTLR report eschewed an online TV sales tax in favour of recommendations for quotas and levies:

“The Yale panel recommendations urge the federal government to similarly compel rival U.S. streaming services in Canada ‘to devote a portion of their program budgets to Canadian programs.’”255

My critique in Playback256 added jobs data to the arguments. I called out the report’s modus operandi as a quid pro quo that recommended trading consumer rights to support to less than 1% of all the jobs in Canada. With respect to recommendation #60 that relitigated the well-worn mantra that all media content undertakings that “benefit” should “contribute,” I tried to set out facts. Not for the first time, I pointed out that broadcasters benefit from the regulatory bargain, receiving a 30% audience boost from simultaneous substitution in return for a 30% spend on Canadian content, rendering the broadcasters’ contribution a net zero and the playing field already level. I also suggested that replacing production funds could be easy, if that was the only goal. A straightforward fix could be to switch up the money source from decreasing broadcasting and cable technologies to the increasing broadband and wireless technologies. Since all four delivery technologies are owned by the same conglomerates, the ongoing creative destruction of the two old ones should be no harm, no foul. Such a switcheroo might require revisiting a 2014 Supreme Court decision ruling that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) could not be considered broadcasters, a condition that was simply no longer accurate.257

The most important observation about the BTLR may be an omission that seems a priori: The panel did not recommend The Act be updated to reflect the fundamental role of audience in today’s global media market.

The BTLR report had been timed to release just before the 2020 PrimeTime Ottawa. Minister Guilbeault would be the opening keynote Thursday morning, January 30 and would be interviewed on the main stage. As per the previous year, I was in the room. Excitement was evident in the warm-up speeches. The event began by congratulating the BTLR panel. Putting Guilbeault on the spot, but pleasantly, the industry wanted to know when the government would table legislation to compel Netflix to contribute and level the playing field? The Minister graciously reported that his staff planned to deliver legislation by June. Everyone seemed happy. What a difference from a year earlier when, on the same stage, Netflix had been called a “cultural imperialist.” On a panel later that morning, when an award-winning Canadian producer observed that the “sector had never been more buoyant,” I smiled to myself. This buoyancy was, of course, owed directly to the foreign giants. A hundred years on, Canadian tolerance for irresolvable paradoxes was in full swing.

Over the next few weeks, the BTLR was the topic of more industry events. The last in-person presentation on the report that I attended was a lecture at Ryerson University by CRTC. My takeaway from this small event is important because it seemed to confirm the long-term entrenchment of the industry’s shared thinking and the strength of its immune system. The speaker emphasized a point that contradicts this book’s core argument, telling students that Hollywood is successful because of the economy of scale afforded by the large U.S. market. To me, this claim that Canada’s small population causes market failure of Canadian prime time TV is a core myth (in research terms, a confirmation bias) that prevents change by overlooking the structural fault that is the true culprit of the so-called market failure. Hollywood TV is successful for one reason: its value chain is structured to reward popularity and its financiers have a relentless need to succeed. By contrast, a need to succeed with audiences is MIA in the Canadian policy structure. Moreover, in a global TV market, the size of any domestic market no longer applies, even one that is only 4% of the global population, i.e. the U.S.! Staying silent, I listened to students ask questions reflecting their experience as global media citizens who don’t get “Canadian content.” Afterwards, CRTC invited me to lunch on their next visit to Toronto or mine to Ottawa. Thanks to coronavirus, neither trip was to be. I’d be delighted to zoom anytime.

It was a wrap. Let’s Talk TV, Creative Canada, Harnessing Change and the Broadcasting and Telecommunications Legislative Review comprised a four episode series that explored ways to future-proof Canadian TV. One might wonder: Was the Canadian industry in the TV hearings business or the TV business? While Let’s Talk TV and Creative Canada Policy Framework faced forward and took steps towards globality, regulatory capture seemed to follow. With Harnessing Change and the BTLR, arguably policy had backtracked such that serving audiences was out again and protecting old models was back in. Perhaps legacy stakeholders had been so persuasive that the government seemed willing to sacrifice Canada’s position on net neutrality to satisfy vested interests and extant entitlements. Well before coronavirus, time had already been lost, as a CEO framed it:

“There is a ticking clock. We worry about it all the time. I think the industry has done a very good job with both the federal and provincial governments. But at some point…”

Suddenly, the clock did stop ticking, but for an unimaginable reason. On March 11, 2020, the global pandemic became official and just like that, time stopped for everyone and everything, including TV productions.

As things slowly came back into focus there were two TV initiatives in the foreground. Firstly, the Canadian government moved to support the creative industries during the crisis and to address industry inequities that the pandemic starkly revealed — as did governments around the world. As part of a $28M emergency support fund for cultural, heritage, and sport organizations, $19M was set aside for film and TV productions.258 Subsequently, a $50M fund was added to support productions without covid-19 insurance.259 On the diversity front, Netflix started the Banff Diversity of Voices Initiative;260 and much more is in the works, as explored in the very successful, universally accessible, 2 week long virtual Prime Time 2021, excellently produced by CMPA.

Secondly, on November 3, 2020, the government tabled Bill C-10, the first draft of legislation based on the recommendations in the BTLR report of January 2020. The legislation did newly define online streamers as broadcasters and proposed bringing them into the regulatory system. It proposed achieving this by expanding CRTC powers, aligned with the BTLR suggestions. The Minister suggested this could result in up to $830M in contributions to Canadian music and TV by 2023.261 As always, reviews were mixed. Critics observed that the bill preserved the status quo, i.e. the long held perception that Canadian production sector was weak, arguing that Bill C-10 would “increase consumer costs in the long term, and leave behind a market that perpetuates unfortunate perceptions of Canadian content as a weaker product reliant on government mandated support.”262 To further entrench my role as a skunk at the picnic, I will add five observations on Bill C-10 that relate to this book’s core arguments:

- An omission in the BTLR, and subsequently Bill C-10 is a recommendation to revise the iconic Section 3 of the Broadcasting Act to shift from a supply driven to an audience demand driven Canadian TV system, so as to reflect the pivotal potential of must-see content and global reach, i.e. a shift to the goal of globality.

- If the policy goal were simply to replace CMF funding that is decreasing due to the decline of cable delivery, some have proposed a straightforward remediation: change the source of CMF funding from cable to broadband and wireless, the two growing delivery technologies. Since Canada’s media conglomerates are horizontally integrated — own all delivery technologies — this could be implemented as no-harm, no foul. However, the Supreme Court has confirmed that Internet access is a telecom service — not broadcasting — so there is no simple way to do this, which leads to point #3…

- A second policy option to maintain funds for Canadian content would be a federal sales tax on digital services. As discussed, many jurisdictions around the world including Quebec and Saskatchewan have already successfully applied sales taxes to foreign online services. Directing the proceeds towards Canadian entertainment would be a separate negotiation,263 but such a policy shift seems doable. (Please note that as of March 2021 a federal sales tax on digital services has been informally announced.) This suggestion (3) and the previous one (2, above) follow from similar logic: If Canadians want to continue feeding the same policy framework, i.e. financing Canadian content that doesn’t have a globality record or goal, Canadians should continue to pay for it.

- An implication of recommendation #55 in the BTLR, on which some of Bill C-10 is based, seems overlooked: ownership. If Canadian ownership becomes irrelevant to regulatory capture, the flip side is the question of what would prevent Canada’s large communication companies from selling out to international buyers? If Canadian broadcasters are expected to compete with global streamers for Canadian content and audiences, they can be expected to demand removal of foreign investment restrictions (a.k.a. Canadian ownership rules). This could have cascading consequences for telecom carriers and even for Canadian content.

- And finally… If the argument in this book is accepted and a new policy goal would be set (globality), why would Canada force global streamers to contribute to a 20th century framework which has not yielded results, over five decades, that demonstrate efficacy at Canadian content that Canadians (and the world) do watch. After nearly 50 years of the extant framework, 90% of Canadian audiences do not watch Canadian content. Yet, Canadian scripted fiction is 40% publicly funded, the bulk from federal and provincial tax credits, and CMF funds return a 2% ROI. Paradoxically, CMF funds — and broadcasters’ profits — derive from the popularity of other countries’ hits. Moreover, Canadian broadcasters’ “work around” is to direct their Canadian content investments towards lifestyle content they can, and do, monetize globally.

As 2021 got underway, a Canadian TV policy reckoning was yet to come. Had fear or groupthink taken hold? Not even the shock of the shutdown, which increased demand for streaming about 40%;264 — or the Schitt’s Creek schweep that exemplified globality — or Netflix’ announcement that they’d spent 2.5B in Canada since 2017 and would open a Canadian development office265 — had sparked determination to address the most critical thing missing from the outdated policy framework: audience.