PART III/THE FUTURE: HOW CANADA CAN MAKE GLOBAL TV HITS

CHAPTER 7

FIVE STEPS TO GLOBALITY

“Make sure you know what the market wants. Understand your competitors. Make sure your product is commercially viable outside of Canada. It’s no different than if a drug for life sciences or clean technology… If you want to sell to a global market, you’ve got to create for a global market.”266

Welcome to Part III of Mediaucracy. Having analysed the root cause of Canadian TV’s market performance, reviewed the 100 year policy history, analysed its value chain, and looked at TV hits from other countries around the world, I hope you will agree on an urgent imperative: innovate policy to seize opportunities in the global, online TV era. The unintended consequences of disruption have included the destruction of the policy regime’s core rationale — a small domestic market. The upside is clear — the opportunity to capture attention on the world stage.

Noreen Halpern, award-winning producer and founder-CEO Halfire Entertainment (Another Life, 2019-2021, Netflix; Alias Grace, 2017, CBC and Netflix), put it perfectly:

“How can we work to bring people together? We should start by getting far more strategic, because television is getting better and better around the world and the bar is being set much higher. How do we maintain our ability to be strong Canadian creators? There have been some wonderful ways of ensuring Canadians get money to produce, but as we move forward, only the best shows are going to survive. Canada can recognize we have this unique place and take advantage of it and figure out a smart way to improve on what we’re doing. There must be policy changes that focus less on Canadian broadcaster support since there is less and less of that, and focus more on encouraging and supporting strong new Canadian voices that can share our stories with the world.”

Does the 40 year old point system need to be disrupted? Likely, but the far more urgent priority is to agree on the new goal. By now, my view of this goal should be clear: must-see content with global popularity. The caveat is that structural change to incentivize globality must be achieved without harming the hard-won results of the extant framework: world-class production capacity. There should be comfort in understanding that policy that incentivizes globality will further accelerate demand for Canadian production services.

It’s time for a new view. The extant structure is unsuitable to seize opportunities in the global, online era. Public funding is largely controlled by the broadcasters: gatekeepers who are running on old technologies, are themselves protected, and have no need to succeed with domestic or global audiences.

Philippa King (former VP, marblemedia and Head of Business Affairs, Rhombus Media) observed that the structure has become a disservice to Canada’s hard-working producers:

“We spend so much time protecting our little world — protection doesn’t work anymore. We have to learn to compete.”

Not awarding public funding on a basis that rewards market performance contributes to the premium TV policy fail, as noted by Len St-Aubin:

“When it comes to premium content, public policy and CanCon financing incentivize broadcasters to be spenders — not inventors — opposite to the policy goal. Ironically, broadcasters are incentivized to acquire Hollywood hits they can monetize in Canada (via simsub) and to spend on Canadian fiction and documentaries to meet regulatory obligations. Then they do invest in genres that don’t qualify for Canadian content financing, such as lifestyle — that they can own and monetize on the world stage.”

Combined, the features of the policy framework fail to create a robust feedback loop that would drive all the players to pull in the same direction in order to increase market success in premium content. While it has become trendy for the government to finance both development and export, especially since 2017’s Creative Canada Policy Framework, more public funds won’t deliver market results unless the R&D is linked to ROI.

In this final chapter, I propose a goal-driven, actionable policy plan to get it done: incentivize market performance. Before sharing a five-step critical path to globality, I will share two observations that bubbled to the surface while I was working on this plan and was reminded of great advice from Einstein: “You can’t solve a problem with the same level of thinking that created it.”267 If the following two observations are accepted, they might shift policy thinking to the new level required to achieve globality. The first concerns industry rage against the so-called foreign giants. The second is around the term Canadian content, a.k.a. CanCon.

Firstly, considering the industry’s anger at the global streaming companies, it bears repeating how foreign media giants were inventively deployed to build Canada’s 20th century broadcasting system. Canada didn’t threaten to levy ABC, NBC, or CBS. To understate, foreign TV giants were welcomed and provided the system’s money via simultaneous substitution and the 4+1 cable package rule. Access to U.S. TV was built into the policy framework, reflecting the stipulation in the Broadcasting Act that Canadians should have access to the programs they demand. These remarkable results render the persistent rhetoric of protection, with its subtext of invasion, rather empty. It seems time to end the campaign against foreign giants and time to make a plan to collaborate to achieve a 21st century TV goal: globality.

A second problem is the term Canadian content. Thousands of pages were penned on the its definition, until it was practically defined as content that fulfills the requirements of the 10 point system. Its definition is yet debated in 2020’s Bill C-10. My suggestion is to solve the problem in the same way that texts are best edited: If in doubt, leave it out. As Charles Falzon, founding CEO of the CMPA (then CFTPA) clarifies, Canadian producers’ focus on making their show officially CanCon has evolved as an unintended consequence:

“The point system was meant to be originally much more of a free system, then government investments started clouding the issue: What does it mean to have a Canadian cultural versus an industrial agenda? That got really foggy because people started getting into figuring out ‘How do I take this project, which could be an industrially commercial success if it’s good and if it’s watched, and wrap it up in a maple leaf?’ In doing so we become neither fish nor fowl. Are you focused on making sure you create a commercially successful project?”

I often see this type of confusion in my graduate students who don’t get CanCon. They do understand the mojo of Canadian YouTube producers, who pay no attention to Canadian content rules because they don’t help with financing content or reward a producer for increasing their audiences. Young people entering the industry instinctively get that when the market is the world, only one question matters. Will it work for the audience? Canadian content is an insider term that references funding arithmetic. What happens in paperwork should stay in paperwork. Not only is the term not audience facing, it may shrink audiences, given its awkward reputation. My suggestion is to stop trying to define it and just leave it out. TV hits from other countries are referred to as Danish TV, Israeli TV, Norwegian TV, and so on. For public discourse, I suggest simply: Canadian TV.

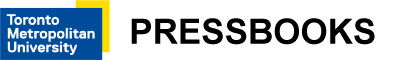

Policy design is a collaborative process. It’s my hope that this chapter will encourage collaboration between policymakers and industry that will culminate in a consensus as commanding of 21st century TV dynamics as the old framework was of 20th. It might be as simple as this: Make globality the new goal and it will happen. A critical path to globality proceeds from a new goal, to new policy purpose stemming from this goal, to strategy, to instruments, and finally, to measurement tactics that enable assessment of progress and facilitate pivots to stay on course towards the goal. Before we dig in, here is the critical path:

New goal: Globality

Canada’s 20th century communications policy framework achieved promising outcomes, and then some. These achievements include telecommunications conglomerates strong enough to adapt to wherever technology leads because they are vertically and horizontally integrated, owning all four current technologies of content and media delivery: terrestrial wireline and broadband, wireless, linear broadcasting, and broadcasting distribution (mostly via cable). More good news is that Canada’s media workforce, once a fledgling sector, is now the global leading edge. Canada’s expansive production infrastructure attracts increasing investment by global studios. However, the policy framework hasn’t delivered globality for one reason: Globality has not been its goal. A new goal seems imperative: TV that meets the growing demand of audiences in Canada and around the world for good stories, well told.

Consumption of creative products is leaping in developing economies across Asia, Latin America and Africa, powered by the discretionary purchasing power of a rising middle class. It’s predicted that by 2030 two-thirds of the global middle class will be in the Asia Pacific region. Nigeria, already the largest consumer market in Africa will soon have the world’s second-fastest growing middle class. The inescapable conclusion is that small countries have a chance to reach mass markets with their media products.268 The power of articulating a goal simply is that it functions like a north star and keeps you on course. As the Cheshire Cat said to Alice: “If you don’t know where you are going, any way can get you there.”269 A clear goal enables every strategy, tactic, and measurement instrument to be evaluated for alignment with the stated purpose to solve the problem: Does this move us closer to globality? Does that?

Or, as U.S. president, Franklin D. Roosevelt said, in July 1938, in a fireside chat purposed to inspire success amidst challenging times, i.e. the Great Depression: “To reach a port, we must sail — not tie at anchor — sail, not drift.” To reach globality, we must sail towards it.

Undoubtedly, these are challenging times in the TV business. Now, as disruption vanquishes Canadian TV policy’s core rationale (small market) and a three-alarm fire devastates its financial pillars (broadcasting, cable, territorial advertising for premium TV), there is extraordinary financial opportunity in the global market. It is widely acknowledged that TV distribution will be fluid for some time. As such, a globality goal will future-proof Canadian TV because it addresses content and the urgency of policy to deliver content that is demand-driven, popular at home, and positioned to reach the world’s growing audiences. Globality is a technology-agnostic goal that will be relevant as long as people love stories, whether they’re produced on a screen, or with AR, VR or technologies unimagined. (If in the future, a happy pill, or more likely an app, replaces the human need to connect via stories, that’s a black swan we can’t worry about now.) Globality will encourage Canadian TV to become self-sustaining, ideally profitable, and to shift mediaucracy towards meritocracy. Eventually, globality will free up public funds to be directed where needed now and in the decades ahead. Globality is achieved via one priority: audience.

Correct identification of a problem is critical to its solution. Since the root cause of Canadian prime time TV’s poor market performance is structural, the problem cannot be solved by tweaking the existing structure. Throwing money at development or export, without adding pressure for popularity, will be an ineffective strategy because money alone, without policy leverage, fails to address the disconnect between R&D and ROI. Setting the right goal may seem facile. However, goal setting may be the hardest part of future-proofing Canadian TV policy and setting it to sail towards globality.

New policy purpose: Incentivize globality

As the saying goes: if you do what you’ve always done, you’ll get what you’ve always gotten. It does not work to meet the biggest media disruption in 600 years with — same old, same old. I propose a two-word, actionable phrase as the new purpose for the Canadian TV policy framework: incentivize globality.

Industry and policymakers know the extant policy framework was not built for the purpose of incentivizing content popularity or global reach. An award-winning CEO said, “Today the rules are not supporting the opportunity to have a real hit. There has to be change.” Karen Thornstone, Ontario Creates President and CEO, succinctly nailed the policy pain point:

“Our system is not about making sure content has a market demand. It was never laid out as a goal, so you can’t expect huge international traction and commercial success out of content that wasn’t designed to do that. It’s ‘done, dusted, on to the next’ because the public system is largely financing these things.”

Even worse than not incentivizing popularity, the current framework even exacerbates the popularity problem because its goal works against popularity by encouraging production expediency. Another award-winning CEO observed that there may always be a role for production incentives, but the problem is the absence of globality incentives:

“Production subsidies are valuable, for the same reason the UK has them, why Hungary has them, why multiple U.S. states have them. Not cultural subsidies, but industrial subsidies designed to create a place of making content. Those should stay in place…. The rest should be done away with. All regulations for broadcasters should be wiped out and all other subsidies should be wiped out and it should be survival of the fittest.”

Before moving on from purpose, it is important to take a deep dive into the concept of purpose. The purpose of long-form, scripted TV is singular: to entertain. Achieving this customer-centric purpose is the sole way to build an audience. An iconic duo, Harvard’s Theodore Levitt and his student, Clayton Christensen270 defined customer centricity as a purpose brand, pointing out there is no such thing as a growth industry, only the evolving needs of customers. They sent the point home by emphasizing customers do not need a five inch drill; they do need a five inch hole. The bottom line is that customers hire a brand to do a job. In the case of premium TV, audiences hire shows to entertain.

From a knowledge cluster on the opposite coast, Peter Diamandis and Salim Ismail define purpose Silicon Valley style, as MTP, or Massive Transformative Purpose,271 observing that the valley is littered with solutions to customer problems that don’t exist. Applied to this book’s argument, Canada is littered with TV shows that don’t entertain. TV that does not move the emotions of an audience to tears, fears, laughter, horror, curiosity or concern, has no chance of becoming a hit. This book’s argument has been that the only way to optimize entertainment value is to link R&D to ROI, a value chain structure that delivers pressure for market results.

Perhaps the most well-known proponent of customer centricity has been Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, who built a $1.5 trillion dollar company on the principle that leaders should work backwards from what is best for the customer, solely because customer benefit is best for a company’s value. Customer obsession, in TV meaning audience obsession, is the singular thing that counts. Moreover, rhetoric without action — or in Amazonian-speak, good intentions — won’t work. At Amazon, long-established practices throughout the company require working backwards from the desired customer experience. Before any new product or service is developed, the first step is to write a press release (PR) for it, including FAQs.272 For TV, it’s easy to see that such a PR would describe a global hit with FAQs about how it was developed, its stars, its production budget, its awards and above all, its record breaking audiences. Laser focus on evolving customer needs moves things forward, while dwelling on the past — not so much. In other words, working backwards (from a future goal) is the opposite of facing backwards (towards the past).

There are two reasons that Canadian policymakers should believe in such a customer-centric purpose. First, Canadian TV is financed by the popularity of another country’s hits. Second, Canadian audiences are among the most diverse in the world. Canadians know that people, no matter how diverse, are more similar than different. If a show resonates with global audiences it will do the same for audiences at home. Hopefully, with consensus that incentivizing globality should be the purpose of policy for the online era, let’s move on.

New strategy: POM to COM

A policy focus on volume worked well for decades, until it didn’t. As media disruption accelerated, senior executives worried about the efficacy of the framework: “If you can do an OK series and get renewed, why would you have to do something brilliant?” Starting in the 1990’s, policy tweaks to improve market performance were tried, but this book has offered an explanation for why they didn’t work: the popularity problem is embedded in the native design of the framework. At least three tactics failed to work: assigning a 1M audience as a hit; requiring more “Programs of National Interest;” and increasing funding to development or export. None of these tactics addressed the critical importance of a financial need to succeed, which is TV’s only shot at popularity. Following the money revealed that the root cause of poor market performance is a systemic flaw in the value chain. This is so important that it bears repeating:

The policy problem is not rooted in the talents of Canada’s creatives or producers. Financial elements drive creative ones, not vice-versa. This definitive analysis solves the puzzle of Canadian TV by finding that a fault in the value chain is the reason why Canadian TV has not matured into a sustainable sector. The 20th century framework, that did strengthen creators and producers, now holds them back. Canada’s producers and creators deserve financial partners who are aligned with their need to succeed with audiences at home and on the world stage.

Attaining globality is close. It means strategic evolution from a Production Optimization Model (POM) to a Content Optimization Model (COM) that would feature linkage between R&D and ROI, with no negative impact on the production phase in the middle of the chain. In short: POM to COM.

A Content Optimization Model (COM) would re-align the interests of development stakeholders around the incentive to succeed in the market. Currently these goals are divergent. A linear broadcaster fulfills their regulatory obligation by committing money to the project, a task basically done assuming the project gets delivered; this puts the pressure on delivery, not market performance. Public financiers and lobby organizations aim to get as much TV into production as possible, putting the pressure on volume. Most financial obligations wind up by the end of phase 2, manufacturing. The result is that monetization becomes a nice-to-have, not a must-have. The only Canadian financiers who need the asset to become popular are producers who risk time, money, and reputation. The other development partners who need to succeed are the studio financiers (increasingly streamers) who acquire ex-Canada exploitation rights, but these are most often U.S. companies because the Canadian system has disincentivized the formation of studios and has disincentivized broadcasters to be investors. The result of this fault in the value chain is that if the project is a hit, the riches (or recognition) don’t even flow to Canada.

But there’s more. Not only does Canadian R&D consist of a jumble of priorities, there’s also a problem at the ROI end of the value chain! Simultaneous substitution effectively drops Hollywood hits into the ROI position. This deus ex machina policy play delivers profits to the broadcasters. Hollywood hits do provide financing for Canadian TV, but simultaneously they erode the need for it to succeed. The presence of Hollywood hits at the ROI end of the value chain defeats the objective of development, rendering the R&D phase a “bridge to nowhere.” A-list Canadians in Hollywood understand this:

“It’s going to take really ballsy players to break out of the system that is in play. Canadian networks don’t care if they make money from Canadian television because they get that money from the government anyway. They buy American stuff to make money.”

It’s also important to observe that other features of the POM, especially the prohibition on broadcasters acquiring global rights to distribute premium TV, contribute to Canadian broadcasters’ disincentive to optimize the asset being developed.

But here’s some great news. A value chain that prioritizes globality naturally co-exists with a strong production sector, and moreover, does so ideally. A Content Optimization Model (COM) is additive to a Production Optimization Model (POM) and does not decrease production strength, rather the opposite. POM and COM do not differ in phase 2, the production phase of the value chain, but only in phases 1, development, and 3, distribution. A COM is how content does become an economic driver, per the goal of the 2017 Creative Canada Policy Framework.

However, value chain adjustment is still a conceptual strategy. What’s needed is a tactic, i.e. an actionable instrument that can execute the value chain pivot, and deliver measurable results.

New instrument: G-Score

I sensed a need for a new policy instrument. Policy CEO Karen Thornstone concurred:

“There’s a fundamental question about whether we need more than one tool to get at different things. I don’t see the incentive for content creators to ensure their content is market-worthy.”

The problem called for a single instrument that could shift the model from a POM towards a COM without harming production. Thinking about this was a puzzle: all the pieces had to fit together. I found inspiration in Canadian music policy history. MAPL for music is attributed to Stan Klees, Canadian Country Music Hall of Famer and co-creator of the Juno’s, Canada’s music awards. Adopted in 1971, MAPL helped catapult Canadian music to world attention by prioritizing creators. And it worked. By 2015 Canadians held seven of the top 10 spots on Billboard’s Hot 100. Undoubtedly it has contributed to continuing strength on the global stage. Canadian Grammy contenders and winners in 2020 and 2021 included Justin Bieber, Drake, Kaytranada, Shawn Mendes, and more.

MAPL is spare yet effective, aligned with the truth of a line written by William Shakespeare from his 400 year old hit, Hamlet: “Brevity is the soul of wit.” The Canadian government has acknowledged MAPL’s simplicity and elegance, two hallmarks of strong policy:

“While it stimulates all components of the Canadian music industry, the MAPL system is also very simple for the industry to implement and regulate.”273

MAPL is an acronym for M (music), A (artist), P (performance) and L (lyrics). To fulfill Canadian content requirements for Canadian radio broadcasters, two of four requirements must be met. Unlike scripted TV, music production requires few jobs. MAPL’s relevance to TV policy is its emphasis on the creative process. It defines Canadian music simply: Music created by Canadians.

M (music)—the music is composed entirely by a Canadian

A (artist)—the music is, or the lyrics are, performed principally by a Canadian

P (performance)— the musical selection consists of a performance that is either (a) recorded wholly in Canada or (b) performed and broadcast live in Canada

L (lyrics)—the lyrics are written entirely by a Canadian

To solve this puzzle, I made a list of 6 requirements that would need to be addressed in order to remove disincentives for TV globality and to add incentives for it:

- Producers would access funds directly: This disconnects producers from legacy broadcasters’ disincentives for popularity.

- Funding would be platform agnostic: This encourages producers to choose whatever distribution arrangements optimize global reach.

- Creatives would be financially rewarded for increased audiences. While no other element is more closely linked to popularity than strong writing, this protects the value of public funds by financially rewarding projects with Canadian showrunners, but not disallowing other choices.

- Overall content popularity would be financially rewarded.

- Global distribution would be financially rewarded.

- Production strength would not be harmed.

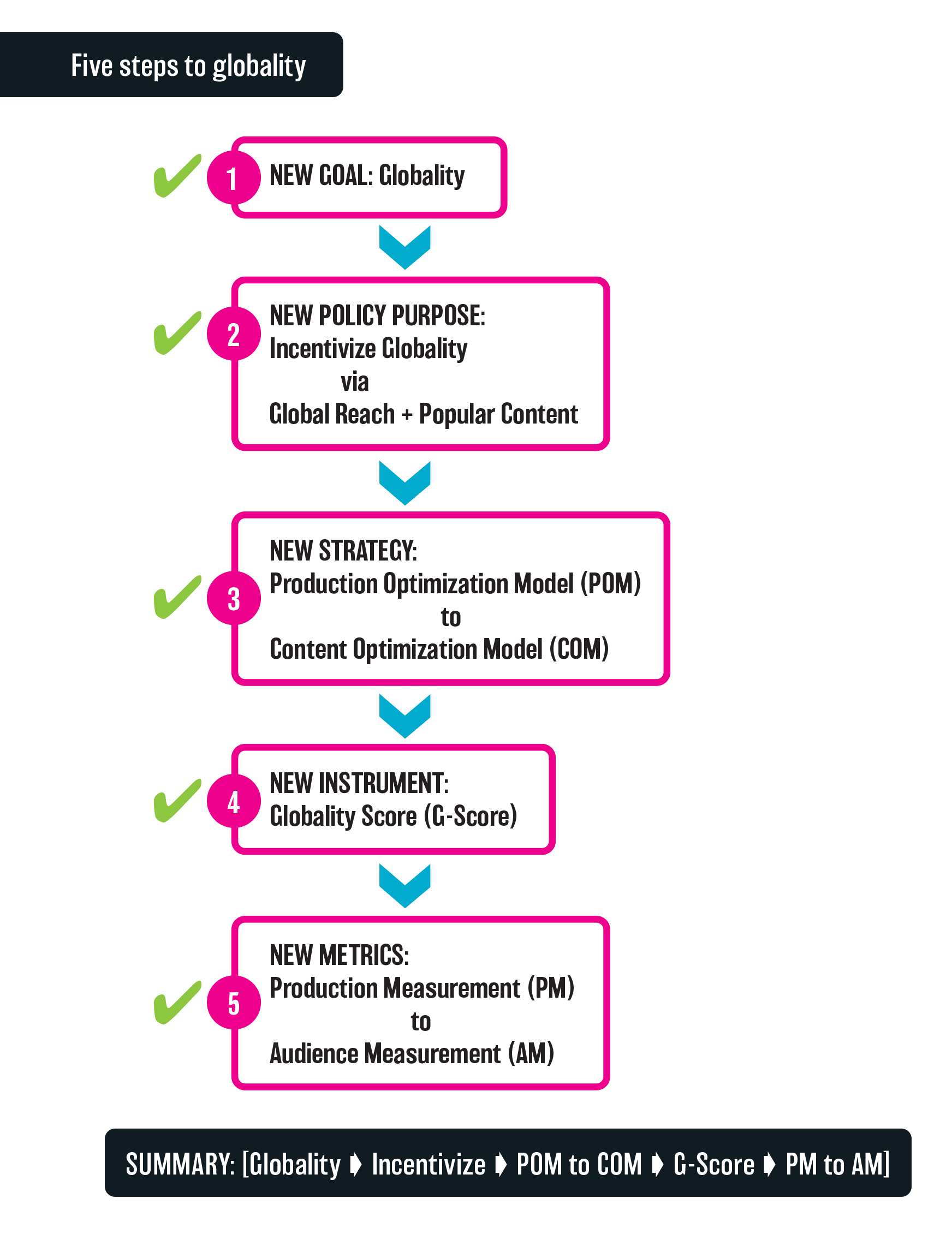

To meet these requirements, I created a simple, 6 part policy instrument that works to incentivize globality by deploying the truth that money talks. Globality Score (G-Score) is a 3 x 2 matrix that is a producer-accessed, platform-agnostic, sliding scale tactic that nudges R&D stakeholders towards ROI. G-Score gamifies the globality goal and creates competition for audiences. It pivots on the the key success factors in TV: audience.

To design the G-Score matrix, I identified four main success factors that affect TV globality. The number one factor is audience size. The other three are determinants of audience size: production company; showrunner; global distributor. Very importantly, G-Score guarantees the value proposition of public money because it rewards funds on a sliding scale that considers a project’s degree of Canadian-ness, factored against audience size:

Let’s break down the G-Score by elaborating on each box of the matrix to see how globality is incentivized and how funding gets scored. Along the left side of the matrix are the three critical development stakeholders. The production company manages the key elements of the project, including creative, production, distribution, and the relationship with the financiers. The showrunner gives the project its best chance at popularity. The distributor (or distributors) finance production in return for global exploitation, thus giving the project reach to large audiences. Together, this triumvirate of stakeholders — producer, creator, distributor — arms the project with its best chance at globality.

The Production company is the first point of the G-Score. Production companies would apply for G-Score funding directly without a gatekeeper and regardless of the platform on which the project will be distributed. This is critically important because it is only the distribution sector that is in rapid evolution. As a basic protection for public funds, the production company must be a registered Canadian corporation whose arena of business is TV production. However, other aspects of the company’s track record such as slate of projects, number of employees or length of time in business are not key to G-Score. As such, there is no need for complicated paperwork because the other factors in the matrix cover off the most important factors for globality: creative, distributor, audience record.

Showrunner is the second point of the G-Score. Fundamental to this book’s argument is the pivotal role of writing in determining the potential for popularity (of course, acknowledging the inherently high risk in the TV business). Because there is often vagueness around the title “creator” or “created by,” this point is determined by the writer who has been contracted as showrunner for the pilot (if there is one) and/or at minimum, Season 1. G-Score rewards, but does not require, that the showrunner be Canadian. Since the potential financial and reputational rewards for choosing the best writer for the project far outweigh the advisability of a choice pivoting on nationality, producers are free to choose a lower G-Score. Therefore, the G-Score will end the practice of complicated paperwork around who is the creator. But even if the showrunner is not Canadian, there are still important benefits to the Canadian TV system.The best showrunner, of whatever nationality, will run a writing room that will, by default, uplevel junior writers and encourage the training of Canadian writers who can learn from the best in an apprenticeship setting.

Global distributor is the third point of the G-Score. Also core to this book’s argument is that large audiences are fundamental to achieving globality because Canada’s domestic audience is not large enough to deliver meaningful ROI even if a show is a hit. Given the long-term disincentives of the extant policy framework to encourage the formation of studios that acquire global rights for content in order to exploit them, this G-Score point may be the most difficult to achieve. Yet, the rationale is solid because demonstrating global reach and studio formation are capacities that need to be incentivized. The logic is that if a Canadian company is the global distributor and the show is a hit, the money will flow back to the Canadian system. As sources observed, this could mean hundreds of millions split between the public and private stakeholders. Therefore, no project will reach the top funding level of G-Score without acquiring a Canadian studio as a global distributor. What existing entities can fulfill this role? On one hand, some Canadian producers already have distribution arms. On the other, Canada’s media conglomerates are also well positioned to take on this role. Current policies impede or disincentivize this evolution from either starting point.

Audience is the entire right side of the G-Score matrix. Hollywood practice is to set a creative team’s worth by evaluating its previous record. There is truth in this trio of industry adages: “All hits are flukes;” “all you have is script and cast;” and “you’re only as good as your last gig.” All these truisms reflect the difficulty of predicting a hit and help underscore that audience record has evolved to be a TV financier’s Best Available Option (BAO) against the daunting risks of investing in a TV project.

How to incentivize larger audiences via G-Score? Incremental rewards seemed the best strategy, i.e. making it a competition or in other words, gamifying the globality goal. As I thought this through, it made most sense to initiate G-Score by pegging audience calculation from the largest audiences in Canada previously attracted by a showrunner or producer on a previous show — whichever record is better. A preliminary line has been drawn at either above or below 1.5M Canadians or 15M globally. The rationale for this audience “line in the sand” evolves from historical evidence, as presented earlier, that 1.5M has tended to be the largest domestic audience received by Canadian English-language TV shows. Perhaps not coincidentally, 15M, or 10x this Canadian audience number, has also been a stable, conservative estimate for a large audience over the 7 decades of U.S. TV. For the purposes of calculating the G-Score, a 15M audience may be aggregated from anywhere. The result is that level A is somewhat aspirational, even for experienced teams, while level B is designed to incentivize junior teams to achieve greater globality. A project by a first-time Canadian producer who decides to take a chance on a first-time showrunner could still be eligible for funding at the lowest level.

G-Score encourages newcomers to get into the globality game. I use the word game intentionally, because gamification incentives are more effective 21st century policy levers than 20th century quotas. Carrots, not sticks, are strong policy choices in today’s media ecosystem of infinite abundance.

It’s worth noting that it would be ideal to design an algorithm that would combine the audience record of the team domestically and globally to come up with a merged ranking. For the purposes of this iteration, I kept it simple to ensure that the principle is clear: audience is everything.

Calculating the G-Score is straightforward. The 3 x 2 matrix is scored on the left side with 1-3 points for development stakeholders and A or B for audience category. For example, a score of 3A, the top score, would describe a project by a Canadian production company with a Canadian showrunner with a record of a hit, and globally distributed by a Canadian company. A middle funding level could be achieved with two Canadian development points and a B-level audience. Minimum funding could even be received by a Canadian production company with no other Canadian components. Such scoring encourages new entrants and encourages neophytes to team with more experienced partners as it incentivizes the overall goal of globality.

What about IP? It’s time to talk about an elephant in the room: IP rights. I had deliberately excluded IP rights from G-Score until one of my previewers asked me: why? The simple answer is that IP ownership is missing from the G-Score because it is not relevant to achieving globality.

The valuable right in TV, as in nearly every other commercial product, is the ability to access customers – the more the better. In Hollywood and other locales where domestic TV production is robust, TV production has always been a fees-driven business. Historically, producers make money by selling the exploitation rights to a studio — which today may be virtual — in exchange for financing development, production, and distribution. Lack of an investor who is all-in on the project — invested — destroys the essential DNA of premium TV: pressure to optimize the writing, which is the key to maximizing the audience.

Policy support for Canadian premium TV is mainly grounded in two levers imposed on two sectors: On one hand, CRTC regulates broadcasters, mostly via expenditures. On the other hand, public funding measures help independent producers, mostly via subsidies. These measures were intended to be mutually reinforcing, but there has always been an underlying tension. IP rights have become the crucible in which this tension between broadcasters and producers plays out. Tension between broadcasters and producers has moved beyond problematic to counterproductive. Policy is now disincentivizing Canada’s potential partners from pulling in the same direction.

Canada came by the IP misunderstanding honestly. Historically, the policy requiring IP ownership by independent producers as a prerequisite for public financing was driven by the need to develop a nascent production industry. That goal has been spectacularly achieved. Not only does Canada now boast a world-class, in-demand TV workforce and infrastructure, a slew of Canadian production companies — Boat Rocker, eOne, Halfire, Nomadic, Thunderbird, and more — have been producing premium TV for the global market. Yet, they are not incentivized by policy to take on the role of studios. Other producers focus mostly on making a business of so-called service productions. Meanwhile producers who haven’t reached global scale have unrealistic expectations of how the industry works. Former CEO of Entertainment One Television, John Morayniss, weighed in on how Canada’s perspective on IP goes against best practices:

“Small Canadian producers are trained to think they have to hold onto all their rights. Really? The biggest producers in the U.S. would never think: ‘I’m not going to work with the studio. I’m just going to market on my own. I’m going to do everything.’”

A corollary problem with IP is the broadcaster dynamic observed earlier by St-Aubin, that public financing policies also disincentivize Canadian broadcasters from investing in Canadian scripted TV. Instead, they spend on Canadian scripted TV to meet regulatory obligations (and also on Hollywood hits they can monetize in Canada). The analysis is further supported with his pivotal observation that Canadian broadcasters have become significant investors in content they can globally monetize, such as lifestyle. Disincentivizing broadcasters from being real investors in premium TV precipitates a policy fail that works against globality. Global reach via the popularity of must-see content requires that all stakeholders be aligned in order to optimize the asset for exploitation. This process must begin in development, where my sources warned: “All the damage can be done.”

As demonstrated by in the value chain analysis, which followed the money in Canadian premium TV, R&D is a jumble of misaligned priorities that — even worse — do not link to ROI. Canadian broadcasters are a flawed stand-in for studios because they are tasked with managing the development of premium TV (R&D) but lack the key motivator: market pressure to succeed with domestic or global audiences (ROI). Calling Canadian development a “bridge to nowhere,” a Canadian A-list Hollywood showrunner described the impact of this framework:

“What’s happening is the lack of a studio system in Canada. In Hollywood, networks licence content versus studios, who finance content. They say: ‘We’re not going to put up $80 million and let you guys fuck it around.’ When you create a show here, if the studio sniffs any weakness they jump in with you, helping in every way because they don’t want to lose on the backend.”

The unintended outcome in this decades-old issue between producers and broadcasters is a weak link in the policy framework, such that neither side is incentivized to take on the studio function. In many cases, profits have left the country because foreign entities have long been engaged in the studio business, the quintessential economic role in the TV biz. John Morayniss related a story of how stepping up to the challenge of his company becoming a studio paid off, even without policy support:

“A U.S. network was ready to order a show, but the show needed a studio partner that could finance and manage development, casting, production, and post: Everything a studio does. If more money was needed, it would come out of our pocket; but if the show worked, we would make money. We suggested Canada as a location and explained how the CanCon rules could save money. They said no: ‘We’d rather put up more money and get the show we want. We’re building an asset. We need this to work.’ Out of 6 studios that made pitches, we were the only Canadians. We were chosen. We spent a million dollars more to make the show better. We had done our financial analysis: If CanCon, we’d get this; not CanCon, we’d get that. We were wrong; even we didn’t know the value of good content. At the end of the day, we got much more money doing it non-content than we’d ever get doing it content. Even in Canada, we got four times the licence fee we would have gotten.”

A deep reason for the underlying policy problem in Canada — R&D disconnected from ROI — may be as simple as historic misunderstanding of how difficult it is to create great TV and that only the extreme pressure of financial risk is up to the task. The bottom line is that policy tension around IP rights is a false fight. Broadcasters and producers are not enemies, or even frenemies. They are potential partners with the same goal. In today’s dynamic, whereby linear broadcasting’s strength has diminished while Canadian production has strengthened, these potential partners have more mutual interest than ever: To build on success by making TV that wins the global battle for attention.

IP is not a Gordian knot in the Canadian system, an unresolvable problem at the heart of the matter. Policy rules can be changed. For example, none of the countries reviewed in Chapter 4 includes IP ownership as a requirement for public funding; yet all make TV hits for the world stage. The conflict around IP ownership is a red herring. It’s a distraction, an outdated policy holdover that works against globality. A Canadian approach that incentivizes the power of market forces on premium TV should be considered. G-Score is such an approach. That’s why IP is missing.

The conflict between this position and others in the industry around IP might even be partly semantic, i.e. what is meant by IP. Perhaps IP could be interpreted more simply, as the need for strong creative that will win the battle for global attention. In this respect, some common ground and a spirit of collaboration can be found in these words from CMPA CEO, Reynolds Mastin:

“If we’re going to be successful in the next ten years, industry and policy has to have an IP centric focus. By this I mean concentrated resources and strategic thinking around the development of Canadian IP and its exploitation. Four pillars support an IP centric strategy. One is to configure our system to support development to ensure the best possible IP is produced. The second is how do we retain and attract our talent. Three are policy incentives around IP retention by Canadians, which could take the form of terms of trade, codes of practice, changes to tax credit rules with respect to producer control, or changes to CMF rules. The fourth is broadcasting regulation, if you define broadcasting to include streaming services.”

Where will the G-Score money come from? G-Score implementation may not require new money. Recent public funding programs purposed to boost development and export capacity have been created in the absence of any structural change that connects these funds to each other or linked to measurable market results. However, throwing money at these two systemic weaknesses won’t fix the policy problem unless they are structurally linked to audience performance. For example, some export funds are defined as non-repayable contributions. A suggestion is that some public monies for development and export be used to finance the G-Score matrix. G-Score does link R&D to ROI. G-Score will strengthen development and export as it nudges the system towards globality.

Do no harm. A priority of G-Score is to do no harm to the production sector. It is compatible with the existing point system and has been designed to be road tested as a market performance bonus over the top of the current production point system, which for now functions as an industrial incentive. Policy innovation takes time and collaboration. For proof, look to Canadian TV’s last two big policy innovations from forty years ago, simultaneous substitution and production point system. Both initiatives were driven by industry lobbying for their sector’s needs. Designing each of these policy innovations took years of industry-government collaboration and the results speak: today’s broadcasting, advertising, and production sectors.

Similar to MAPL for music, G-Score also redefines, or more precisely undefines official Canadian content. G-Score rewards TV that is created, produced, and/or distributed by Canadians for a global audience.

Overall, the G-Score matrix encourages four types of improvements in the system. All four are consistent with TV industry best practices.

First, G-Score organically incentivizes mentoring. It encourages inexperience to marry experience, which is how to strengthen an industry. For example, a neophyte producer can join forces with an experienced production company who may be able to hire the producer’s dream showrunner and increase the G score. Similarly, G-Score rewards a Canadian distributor who believes in a team enough to acquire global rights on a project, which is another way to increase the G-Score.

A second type of upleveling is G-Score’s inherent philosophy of audiences: the belief that audiences all over the world are more similar than different. G-score implicitly assumes that domestic popularity will predict global popularity and vice versa. Put simply, domestic and global popularity are one and the same. An example of this dynamic is that Schitt’s Creek began trending #1 on Netflix in Canada after sweeping the 2020 Emmy Awards. Its popularity resulted in sales to broadcasters across Europe, increased global interest so much that the show is now available in 197 countries.274

Third, G-Score gamifies competition for audiences. The audience vertical can be adjusted upwards as more shows break the 1.5M barrier, in order to keep audience size aspirational. An annual financial prize for the highest audience could add to G-Score’s efficacy. G-Score inserts competition into the Canadian production community and makes the numbers matter, repairing the disincentive expressed by one of my sources: “If the numbers don’t matter, why compete?”

Finally, G-Score addresses the widely acknowledged data desert around audience data and TV export. Numerous reports have observed a data deficit in export market data for Canadian TV. For G-Score to work well, this capacity will need to be strengthened, which overall will improve the system.

In summary, the G-Score matrix is an instrument that operationalizes the globality goal. Its policy purpose is to incentivize globality. Its policy strategy is to evolve the system from a POM to COM without doing harm. Aligned with best practices in modern policymaking, G-Score gamifies competition for audiences with carrots (i.e. rewards) not sticks (i.e. quotas). By incentivizing Canadian TV to win the battle for attention, G-Score will help transform the framework from supply to demand driven. Domestic and global popularity will help financially future-proof Canadian TV for the coming decades.

New Metrics: PM to AM

The value of data lies in the questions going in and the insights coming out. It will be essential to be smart about collecting data that measures progress towards globality. Regular measurement is essential in a rapidly transforming ecosystem. Ideally, measurement methods should be varied and comprehensive, which means deployment of both quantitative and qualitative tools, because each data type has strengths and weaknesses. Quantitative data sets are large, such as digital big data or surveys, and are best at describing a behaviour or trend. Qualitative data sets are typically small, such as interviews and focus groups. They are best at probing causality, i.e. the why something is happening.

The types of metrics deployed in Canadian TV have not changed much in decades. The emphasis has been various ways of counting production volume. Let’s call these metrics Production Measurement (PM). The categories include the amount of money invested, the number of jobs created, the volume of Canadian content productions, sliced and diced for provinces, gender and genre. These rather blunt arithmetic metrics measure progress by volume and supply, but they will not measure progress towards globality. In Silicon Valley these metrics would be called vanity metrics. They describe the contrast between measuring old fashioned Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) versus the more modern Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) that measure progress towards an explicit goal.275 In TV policy, KPI’s might measure the fulfillment of exhibition or expenditure quotas, but such metrics do not improve market performance. In contrast, OKR’s might state an aspirational objective as a 1.5M domestic audience and deploy audience metrics to measure whether those audiences have been achieved. Other advantages of a goal-driven approach is that, in addition to incentivizing growth, it simplifies regulation and reduces the misstep of tweaking things that are irrelevant to achieving the goal. In order to measure progress towards the goal of globality, the Canadian system needs Audience Metrics (AM).

A data deficit around globality became evident during my YouTube research. Since Canada has been advocating for the importance of Canadian content for five decades, I wanted to compare data about legacy Canadian content with a parallel question to one that we asked Canadian YouTube audiences: “Do you search for Canadian content on YouTube?” The answer, in our study, had been that 90% of Canadian YouTube users said they did not search for Canadian content on YouTube. Our respondents were clear that they do search for the best version of what they’re looking for, regardless of nationality. However, we found that comparable audience data did not even exist for the legacy system. Over five decades, it didn’t appear that the question had been asked. A deductive inference can be made, since 90% of legacy audiences watch global hits during prime time. However, given the cost of Canadian content to the taxpayers, this seemed a remarkable data deficit and a reflection of the framework’s implicit disregard for audiences.

In addition to market performance data and its implications, there are additional benefits to shifting focus to Audience Metrics (AM). These relate to helping to close the data deficit around systemic racism and related data black boxes, issues that have been clearly identified in the critical conversations around addressing and repairing the inequities that have been starkly revealed by the convergence of the covid and economic crises.276

A shift to a globality goal would mean a shift from supply metrics to demand metrics, from production volume to audience size. I propose that Production Measurement (PM) tactics be deprioritized. There should be a new focus on designing, implementing, and prioritizing Audience Measurement (AM): Transforming from PM to AM.

How would PM to AM play out? Envision an industry report that prioritizes year over year (YOY) audience growth, also broken out along geographies and demographics, and ideally, even country by country to help clarify progress towards globality. Robust audience data would answer the question: Where are audiences for Canadian TV increasing or decreasing? The winner of the year’s G-Score prize for the highest audience could be announced on release of the report. Audience stats would no longer be incidental, buried in the final pages of reports. They would be the lead story. Of course, in turn, audience growth will increase ROI on public funding.

Market performance can also be measured with qualitative brand management tools. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder, defines brand as closely aligned with reputation: “Your brand is what others say about you when you leave the room.” Bezos, should know, as in 2019 Amazon overtook Google and Apple as the planet’s #1 brand, and surged ahead further in the 2020 global brand rankings,277 partly attributable to the global pandemic when the company met the rapidly evolved needs of customers. Strong brands wield strong economic power, with the world’s top 100 brands outpacing the growth rate of the S&P 500. While Canada has a stellar global reputation for national values including governance, healthcare, anti-violence, diversity, inclusion, and tolerance, its TV has not often shared a similar reputation.

In addition to building wealth, strong brands strengthen soft power, i.e. goodwill and influence around the world. Downton Abbey (2010-2015, ITV) was called a “national treasure” and a “global phenomenon.”278 The reasons for Canada’s vulnerable TV brand seem straightforward: Its customer has not been the audience, domestic or global. Canadian content’s most important audience has been the government, specifically the government’s need to fulfill the requirements in the Broadcasting Act to supply programs. The policy purpose has not been to incentivize domestic popularity and certainly not globality. Now that we are well into the global, streaming era, a strong Canadian TV brand that is known for delivering great entertainment is necessary, given the abundance of consumer choices. Arguably, a single break-out global hit has helped Canadian TV become a driver of economic and soft power. Well before the Schitt’s Creek schweep, a CEO predicted:

“All we need is one show to become a major prime-time hit and everything will change. Like lightning in a bottle.”

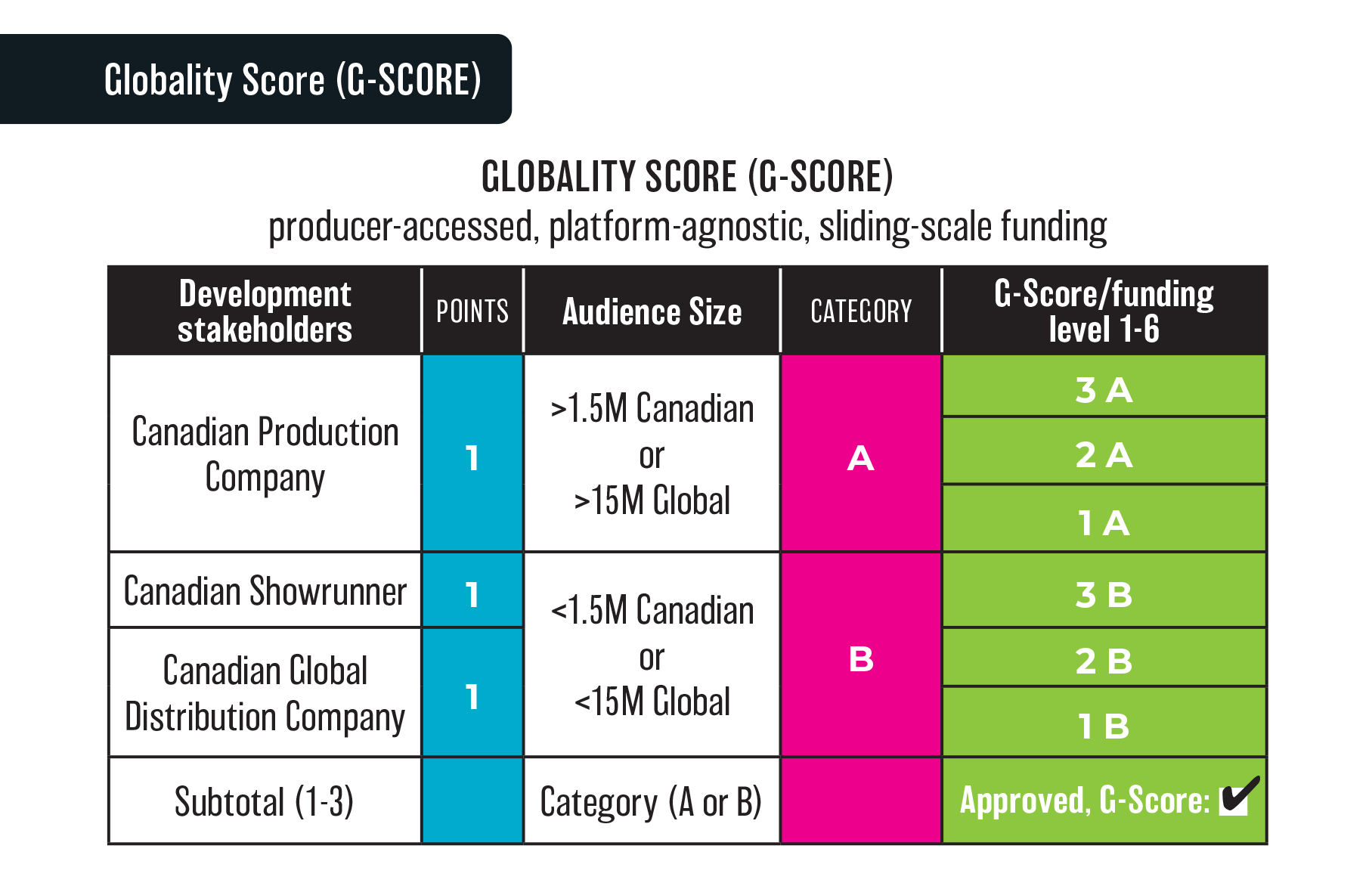

How to measure brand growth? A Harvard-based metric based on exhaustive research, Net Promoter Score (NPS) can get it done.279 The widely acknowledged efficacy of NPS establishes that one, and only one, survey question directly correlates to brand growth: “Would you recommend this service/product to your family or friends?” Audiences who rank the product 1-6 are classed as “detractors.’ 7-8 are “passives.” Only “9 or 10” are “promoters.” The N.P.S. score is calculated by subtracting the percentage of detractors from the percentage of promoters.

The structure of the NPS scale intentionally makes it very difficult for a product or service to score well. While scores range from -100 to +100, only top tier brands get positive scores. Anything over zero is considered a strong NPS. In 2021, Netflix’ NPS score was estimated at 19.280 You may have seen the NPS question pop up in online surveys or on check-out counters, but may not realize its power, which derives from putting one’s personal brand on the line for a corporate one. This dynamic is, of course, the root of the power of online reviews. Going forward, the funding agencies could survey Canadian audiences to probe their thoughts on Canadian content and include an NPS question. All Canadian TV projects, in order to receive public funds, could be required to execute an NPS once their show is in the market. This is because NPS has been proved as the only reliable metric to predict customer growth. Eventually, NPS scores of previous shows could factor into a G-Score audience report. The purpose of including the NPS in a new tool kit for producers is to encourage a focus on audience data and to work together towards globality.

New Outcome: Global TV hits

Explaining this book’s argument to Matthew, a very bright 12 year-old, elicited this response: “You mean on YouTube you only get money if you’re popular, but Canadian TV networks get money just for making shows?”

Exactly. At issue throughout this book has been the imperative to choose the right policy path for the online era: competition for the global market or protection from it. Each type of analysis herein (historic, economic, comparative) has landed on the conclusion that Canadian TV is ready for prime time — global competition. How to play to win?

All media entities that succeed in the global ecosystem possess a globality made of two essentials: global reach and popular, must-see content. This book is a call to action. It argues that Canadian TV must reboot and offers a new tool-kit for purpose-driven, evidence-based TV policy.

Media disruption ignited a three-alarm fire that vanquished the financial pillars of the 20th century policy framework: linear broadcasting, cable delivery, territorial borders. Yet, this same creative destruction has delivered an opportunity for Canadian TV to upgrade to TV’s timeless business model: popularity. This chapter has shown how the goal of globality can be achieved with a new policy purpose, a new policy strategy, new tactical instruments, and new modes of measurement.

When will the job be done? Never. Creating global hits is a high-wire venture. It deserves our best shot because the rewards are substantial. The success of Canadian YouTube producers proves that competition in an open, global market pressurizes content to reach large audiences. The global success of other small countries around the world underscores that a small domestic market is no barrier to success on the world stage. Changing the DNA of Canadian TV means repairing its structural weakness so that it incentivizes globality.

Canadian producers, creators, and distributors are brimming with world-class talent and capability. What they lack is a policy structure to incentivize their best work.

Media disruption is merely the first wave of the 21st century’s Fourth Industrial Revolution. Daunting structural policy challenges abound, and more are coming, not just in TV, but in every arena of public policy. If Canada can’t succeed at rebooting its obsolete media policy framework, how will the nation innovate public policy for banking, biology, manufacturing, medicine, retail, transportation, travel and more? The pandemic is said to have compressed six years of digital acceleration into six months.281 With costly necessities overwhelming the government, it seems more critical than ever for English-language Canadian TV to be sustainable and aligned with Canada’s stellar reputation around the world. It’s time to get in it to win it, and to get on with it. As Philippa King put it: “Aren’t we masters of our own destiny? If we made the regulations, we can change them.”

In closing: Why hasn’t Canada made global TV hits? That wasn’t the goal. Make it the goal and it will happen. The rest is details.

Success is so close and so achievable. Now is the time to make hits, not shows. It’s time for TV policy that incentivizes and rewards globality. Now is the time to prioritize three goals: audience, audience, audience.