Section 3: Socioeconomic Considerations

Chapter 8. Housing Insecurity and Homelessness Among Older Immigrants in Canada

Vibha Kaushik; Christine A. Walsh; and Jill Hoselton

Older adults are increasingly represented in the homeless population in Canada and other Western countries (Canham et al. 2018; Grenier et al. 2016; Woolrych et al. 2015). The rise in homelessness among older adults can be attributed to population aging, shifting age structure, and the added consequences of poverty, economic volatility, lack of affordable and subsidized housing, decreased social programs and social assistance benefits, and increased rates of mental health issues and substance use (Grenier et al. 2016; Reynolds et al. 2016; Woolrych et al. 2015). One under-researched demographic within the older adult homeless population is older immigrants.

Older immigrant adults are likely to face additional risk factors in addition to the known age-related challenges associated with the risk and experiences of homelessness, but very few scholars have explored the experiences of older immigrants facing homelessness. The following discussion explores the existing literature and debates surrounding the topic of housing insecurity and homelessness among older immigrants in Canada; we used an intersectional lens to investigate what is known about these issues in Canadian academic literature and public policy statements with the goal of fostering discourse that will inform future research, housing strategies, community services, and public policies for older immigrants in Canada facing housing insecurity and homelessness.

Who Are Older Immigrants in Canada?

Approximately 300,000 new immigrants arrive in Canada annually. According to the most recent census data, 1.2 million new immigrants settled permanently in Canada between 2011 and 2016 (Statistics Canada, 2017b). The immigrant population now accounts for almost 22 percent or one-fifth of Canada’s population, with Asia (including the Middle East) being the top region of origin (about 61.8 percent of the total recent immigrant population) followed by Africa (13.4 percent) (Statistics Canada, 2017b). More than half of the immigrant population currently lives in large urban centres including Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver (Statistics Canada, 2017b). The 2011 National Household Survey reported that 4.5 million older adults in Canada were born outside the country: most immigrated to Canada at a young age; few (3.3 percent) immigrated to Canada around the age of retirement (Government of Canada, 2017).

Early- and late-age migration are two distinct experiences that shape the lives of older immigrants and reflect the complexities inherent to aging and immigration (McDonald, 2010). For example, an older immigrant who has lived in Canada for 30 years is likely to be competent and perhaps fluent in at least one of the two official languages and to understand Canadian culture better than an older immigrant who arrives in Canada at a later life stage. Some researchers have argued for the benefits of immigrating at a younger age (McDonald, 2010), while others have explored the hardships faced even by those who come to Canada at an early age, including racism and economic and social discrimination that can compound over many years (Brotman, Ferrer, & Koehn, 2020). The life-stage of any immigrants arriving in Canada distinctly shapes their experiences, but all immigrants encounter a diverse range of challenges.

Scholars working in the field of ethno-gerontology have identified multiple layers in the older immigrant experience: factors including race, ethnicity, national origin, and culture all affect the individual and the broader aging immigrant population (McDonald, 2010). The available literature offers important insights into the lived experiences of older immigrants, but it can also simplify intergroup differences and neglect to address important nuances that can offer a more accurate portrayal of the structural forces that lead to inequality among older immigrants (Brotman, Ferrer, & Koehn, 2020). Examples of structural inequities include income and poverty, education, the effects of having a minority status, social capital, the physical environment one lives in, access to resources, and immigration status (Brotman, Ferrer, & Koehn, 2020).

Understanding Homelessness

Homelessness is defined differently depending on the research, practice, or policy context (Grenier et al. 2016). Gaetz and colleagues defined homelessness as “the situation of an individual, family, or community without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it” (2012, par. 1). They further organized homelessness in a typology as follows:

1) Unsheltered, or absolutely homeless and living on the streets or in places not intended for human habitation; 2) Emergency Sheltered, including those staying in overnight shelters for people who are homeless, as well as shelters for those impacted by family violence; 3) Provisionally Accommodated, referring to those whose accommodation is temporary or lacks security of tenure, and finally, 4) At Risk of Homelessness, referring to people who are not homeless, but whose current economic and/ or housing situation is precarious or does not meet public health and safety standards. It should be noted that for many people homelessness is not a static state but rather a fluid experience, where one’s shelter circumstances and options may shift and change quite dramatically and with frequency. (Gaetz et al. 2012, par. 2)

Scholars focusing on homelessness among older adults tend to explore two main trajectories: chronic homelessness (experienced throughout life and into the older adult years) and late-life homelessness (becoming homeless for the first time as an older adult) (Grenier et al. 2016). Another experience of homelessness, among the Canadian-born or immigrant population, is sometimes called “hidden homelessness.” This term refers to “people who are homeless but have not yet resorted to the shelter system (the ‘abjectly homeless’), though they are at high risk of ending up there—or, even worse, on the streets” (Haan, 2011, 44). Many individuals at risk of homelessness reside with their social support networks, resulting in residential overcrowding, meaning households with more residents than what is considered optimal according to the size, value, tenure, and crowding characteristics of the dwelling (Haan, 2011).

Homelessness has well-documented health consequences including shorter life expectancy and high morbidity (Stafford & Wood, 2017). Individuals experiencing homelessness are also less likely to access preventative services, which are key determinants for reducing poor health outcomes (Stafford & Wood, 2017). As a result, those experiencing homelessness have a higher prevalence of later-stage diseases, tend to neglect manageable conditions such as diabetes or hypertension, and have an increased occurrence of preventable conditions such as skin and respiratory issues, leading to more hospitalizations (Stafford & Wood, 2017).

Indeed, the health risks and consequences associated with homelessness are such that they have changed the age parameters for who is defined as an older adult. The standard age that marks entry into older adulthood in Canada is 65 (typically the age of retirement and eligibility for government-sponsored pensions); in contrast, in the context of homelessness, age 50 is considered the benchmark for this life transition (Grenier et al. 2016). Older adults (65+) now account for six percent of the visibly homeless population in Canada and older adults (55+) account for nine percent. These statistics indicate that older adults are a minority within the homeless population, but this could be in part because of higher mortality rates among people who are homeless (Barken et al. 2015; Hwang et al. 2009). The average life expectancy among the homeless population is 39 years (Trypuc & Robinson, 2009), compared with 82 years among the broader Canadian population (The World Bank, 2021). Older adults currently compose about 18 percent of the total population of Canada (Statistics Canada, 2020).

Recent studies have found that both the homeless population and immigrant populations are particularly vulnerable due to a range of factors. Perri, Dosani and Hwang (2020) reported that homeless shelters promote disease transmission because these communal spaces have such a high turnover and are often overcrowded. The homeless population is also susceptible to numerous chronic health conditions that increase the risk of poor health outcomes (Perri, Dosani, & Hwang, 2020). Immigrants, particularly new immigrants, often have lower incomes, which can force them into overcrowded living spaces and multigenerational households, also increasing the risk of disease transmission (Ng, 2021). To date no studies have focused specifically on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on older immigrants in Canada, but the vulnerabilities to risk among both the homeless population and the immigrant population suggest that older immigrants who are homeless are at greater risk of heightened mortality rates as a result of COVID-19.

The high morbidity and mortality rates among the homeless population reflect the significance of access to shelter and housing as a basic social determinant of health and a fundamental human right (Barken et al. 2015; Stafford & Wood, 2017; World Health Organization, 2021). The World Health Organization defines the social determinants of health as “the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. They are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life” (2021, par. 1). In addition to housing, social determinants of health include unemployment and job insecurity, working life conditions, food insecurity, and discrimination that is directly or indirectly connected to housing insecurity. The condition of homelessness is socially determined, so it is futile to treat the symptoms of homelessness (such as poor health outcomes) without also addressing the root problems of homelessness, including social, economic, and relational issues, as well as family dysfunction (Stafford & Wood, 2017). Forchuk and colleagues (2022) assert that it is necessary to focus on measures that prevent homelessness as opposed to investing in strategies to manage homelessness. Possible prevention measures could include efficient social assistance processes and regulations; safer and more desirable housing conditions; affordable housing; increased access to permanent housing; and increased awareness building of social services that can support individuals and families at risk of homelessness (Forchuk et al. 2022).In the context of older immigrants and homelessness, this will require addressing the unique challenges that older immigrants face in Canada.

Multi-Layered Complexities

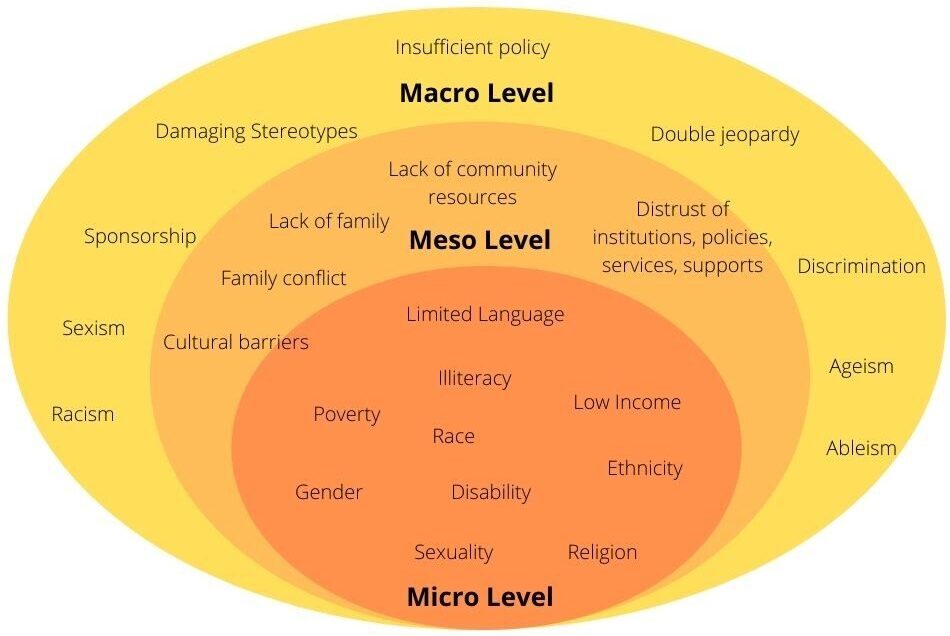

Understanding complex issues like housing insecurity and homelessness among older immigrants necessitates careful examination of the interactions and interconnections among factors at micro, meso, and macro levels. These, in turn, shape the vulnerabilities of older immigrants, influence their capacity for dealing with adverse life situations (Ciobanu, Fokkema, & Nedelcu, 2017), and create pathways that can force older immigrants into homelessness. Use of an intersectional perspective can help reveal the complex interactions among factors that contribute to homelessness among older adults, including older immigrants.

Figure 8.1 Multi-layered complexities of housing insecurity and homelessness among older immigrants

Micro-level: Poverty, Income Insecurity, and Financial Instability

At the micro (individual) level, poverty, low income or income insecurity, and financial instability create a state of precarity that becomes the main driver of homelessness. Low-income individuals experience more income volatility and financial instability even after factoring the effects of taxes and public transfers (Hacker & Rehm, 2020; Ro et al. 2014). Relatively short periods of low income may not lead to negative effects such as homelessness; in contrast, long durations of low income may be defined as chronic low income: a financial state in which combined family income remains under the regional low-income cut-off (LICO) for at least five consecutive years (Picot & Lu, 2017). As discussed below, chronic low income is strongly linked with homelessness.

A dominant theme in immigration debates is the fact that immigrants earn less than Canadian-born workers, and even Canadian citizens born to immigrant parents earn less than Canadians who have been here for many generations (Magesan, 2017; Reynolds, 2019; Statistics Canada, 2017a). According to the Government of Canada’s Longitudinal Immigration Database for the period 1993–2012, 30 percent of all older immigrants in Canada over the age of 65 were classified as having chronic low income and more than 50 percent of recent older immigrants (i.e., immigrants who arrived in Canada 5–10 years previously) were classified as having chronic low income rates. This is roughly three times the rate among immigrants aged 25–54, roughly twice that among immigrants aged 55–64, and is in sharp contrast to the low rates of chronic low income rate among their Canadian-born counterparts: about two percent (Picot & Lu, 2017).

Poverty and chronic low income are the strongest predictor of homelessness (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2021), and most persons experiencing homelessness have limited or no financial resources. People who are living on the threshold of poverty or with high levels of income volatility are often only one “trigger event” (e.g., loss of paycheque; death of/dispute with spouse or family member who provides financial security) away from living on the streets (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2021; Gaetz et al. 2013; Gonyea, Mills-Dick, & Bachman, 2010; Grenier et al. 2016).

In Canada, older adults are guaranteed income security through the Canadian Old Age Security (OAS) program, in which a monthly benefit is paid to all Canadians or permanent residents aged 65 and older. Low-income OAS pension recipients also receive a supplementary monthly non-taxable benefit: the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS). Access to OAS/GIS pensions significantly reduces low-income rates and minimizes the risk of chronic low income among older adults. However, recent older immigrants in Canada are often not eligible for these programs because an eligible person must have lived in the country for at least 10 years since age 18 to qualify. Older immigrants often have short employment and residence histories in Canada, meaning that they may have minimal access to the Canadian public pension system (Kei et al. 2019; McDonald, Dergal, & Cleghorn, 2007). Another issue is that older immigrants who arrive from a country lacking a social security agreement with Canada are more likely to have a low income, because their period of contributions and residence in their country of origin cannot be added to their public pension benefits in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2016). Some scholars have linked the lower pension contributions of older immigrants to the increased likelihood of poverty, which, in turn, is linked to housing insecurity and the overrepresentation of older immigrants in Canada’s homelessness population (McDonald, Dergal, & Cleghorn, 2007).

Unique Needs, Vulnerabilities, and Experiences

Government data reveal that increasing numbers of immigrants and other newcomers to Canada (e.g., refugees) are becoming homeless and ending up in shelters (Government of Canada, 2021). Research has confirmed that various demographic markers create unique challenges for marginalized populations when they live on the streets (Giannini, 2017). Therefore, it is important to understand the needs and vulnerabilities of older immigrants in the context of their overall experiences. These individuals have experienced a discontinuity in their life course as they leave behind the sociocultural contexts of their places of origin, which once provided them with meaningful support in difficult situations (Ciobanu, Fokkema, & Nedelcu, 2017). They may have unfavourable health conditions, have limited English/French language and technological literacy, limited family and social networks, and may experience family conflict, disability, cultural barriers, discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and/or religion, all of which add layers of complexities to the already vulnerable subpopulation of persons experiencing homelessness (Brotman, Ferrer, & Koehn, 2020; Ciobanu, Fokkema, & Nedelcu, 2017). For example, older adults including immigrants tend to experience difficulties navigating government services and may not receive the full extent of government assistance for which they qualify (Ploeg et al. 2008). Older immigrants must also navigate through communication challenges as they try to access social support resources and services including housing support and services for persons experiencing homeless (Hossen & Westhues, 2013; Kim et al. 2013; McDonald, Dergal, & Cleghorn, 2007).

The Government of Canada’s (2021) demographic profile of older immigrants in Canada provides further insights into this issue: about 63 percent of older immigrants (65+) who arrived in Canada between 2012 and 2016 reported being unable to speak either of the two official languages, and older immigrant women were less likely than their male counterparts to speak either official language. This lack of fluency not only creates challenges in accessing services but also serves as a huge barrier to becoming aware of housing support programs and services. Stewart and colleagues (2011) also noted the connection between lack of competency/fluency in official languages and limited employment opportunities, also increasing the risk of low income and poverty.

Homelessness has also been attributed to declines in physical and/or mental health, and persons experiencing homelessness are more likely to have poor health outcomes (Bhui, Shanahan, & Harding, 2006; Kushel, 2020; Rota-Bartelink & Lipmann, 2007). The correlation between homelessness and poorer health levels is stronger among older people (Fajardo-Bullon et al. 2019; Garibaldi, Conde-Martel, & O’Toole, 2005; Kim et al. 2010; Seegert, 2016). Upon arrival in Canada, older immigrants tend to be healthier than their Canadian-born counterparts or older immigrants who have been in Canada for many years. However, over time the health of older immigrants tends to decline, especially among those from non-European countries, and their health can become worse than their Canadian-born counterparts (Gee, Kobayashi, & Prus, 2004; Setia et al. 2012). This phenomenon is known as the “healthy immigrant effect” and has been well documented in several immigrant-receiving countries (Ichou & Wallace, 2019). Older immigrant women are more vulnerable to poorer health compared to older immigrant men (Guruge, Birpreet, & Samuels-Dennis, 2015). People who experience poor physical or mental health tend to lose their ability to perform daily biological, psychological, or social activities and tasks that are normally expected of other individuals of the same age, and are at greater risk of homelessness (Older Adult Council of Calgary, 2018). Together, older age and the poorer health outcomes of older immigrants have implications for their housing outcomes, putting them at a greater risk of homelessness.

Systemic Challenges and Barriers

Experiences of discrimination have also emerged as a major systemic challenge for vulnerable older immigrants (Stewart et al. 2011). When an older person’s immigrant status intersects with other identities such as ethnicity, race, cultural background, gender, language competencies, and socioeconomic status, this creates additional layers of disadvantages with cumulative effects on experiences and perceptions of discrimination and marginalization (Pruegger & Tanasescu, 2007). Together, these can have implications for housing outcomes, especially over time. The experiences of discrimination and perceived discrimination are salient predictors of trust: individuals who experience discrimination or who feel they are being discriminated against are never sure when or where those experiences may occur again and therefore find it difficult to trust institutions, policies, services, and supports (Wilkes and Wu, 2019). However, it is not yet clear to what extent this situation prevents older immigrants from accessing the services and supports needed to mitigate challenges including housing challenges.

The limited welfare options for older immigrants present additional disadvantage related to their status in the country, lack of policy or insufficient policies specifically targeted at older immigrants, and the risk of being portrayed as a social problem (Dolberg, Sigurðardóttir, & Trummer, 2018). One review of Swedish studies on older immigrants who are “less privileged” found that policies related to older immigrants are framed with the assumption that older immigrants have “special needs” and that planners and providers must consider “the problems that they might pose” (Torres, 2006, 1341–42). Ciobanu, Fokkeman, and Nedelcy (2017) raised similar concerns, noting that researchers tend to consider older immigrants a “monolithic group” and to focus solely on age and experiences of migration – when in fact older immigrants are an “analytical category” with high levels of heterogeneity related to many various factors influencing aging and migration.

Other Factors

Numerous factors can influence the housing situations of older adults, but older immigrants can be considered victims of double jeopardy when it comes to housing insecurity and homelessness. For example, many older immigrants live in multigenerational households (Burholt & Dobbs, 2014; Ng & Northcott, 2015). This may suggest strong family connections and housing security, but it may also increase the risk of social isolation and emotional dependency (Government of Canada, 2021; Guruge et al. 2021). Many older immigrants are sponsored by their adult children, which can make them financially dependent on their children; they may have few housing options because they rely on their children to house them (Government of Canada, 2021; Preston et al. 2011). The dynamics related to sponsorship can create pressure and financial hardship for the sponsor and the older adult being sponsored, and can lead to family conflict. Previous research has confirmed that homelessness can be one outcome when financial and family problems become insurmountable (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2021; Government of Canada, 2021). Although multigenerational living is highly valued in some immigrant groups, its sustainability has been questioned, and it is sometimes even considered a form of hidden homelessness (Gubernskaya & Tang, 2017; Luhtanen, 2009; Ng & Northcott, 2015; Preston et al. 2011; Um & Lightman, 2017).

Conclusion

Effective responses to homelessness among older adults, including subpopulations of older immigrants, must be based on a clear understanding of their needs and the challenges they face. These usually involve a variety of micro-, meso-, and macro-level factors. For example, it is vital to be aware of experiences of marginalization across the life course, and particularly in later life. Every person’s journey is unique, and older immigrants may face many risk factors that can negatively affect housing outcomes. The population of older immigrants in Canada is expected to rise, which is likely to be accompanied by more situations of housing insecurity or homelessness.

Few studies have explored the housing crisis facing this vulnerable subpopulation, so scholars have a limited knowledge base, making the development of effective policies and practices very precarious. This chapter has explored the intersections of older age, immigrant status, and homelessness with the goal of informing policy – and especially more targeted research to fill this important research gap. The research community has generally neglected the urgent need to document the current state of homelessness among older immigrants in Canada, and much more work is needed to prepare for future trends. Any research focusing on this vulnerable population should involve listening to the voices of those older immigrants who are at risk – those who are experiencing or have experienced housing insecurity or homelessness.

References

Barken, R. Grenier, A., Budd, B., Sussman, T., Rothwell, D., & Bourgeois-Guérin, V. 2015. “Aging and Homelessness in Canada: A Review of Frameworks and Strategies. Gilbrea Centre for Studies on Aging, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON.

Bhui, K., Shanahan, L., & Harding, G. 2006. “Homelessness and Mental Illness: A Literature Review and a Qualitative Study of Perceptions of the Adequacy of Care.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 52 (2): 152–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764006062096.

Brotman, S., Ferrer, I., & Koehn, S. 2020. “Situating the Life Story Narratives of Aging Immigrants within a Structural Context: The Intersectional Life Course Perspective as Research Praxis.” Qualitative Research 20 (4): 465–84. doi.:10.1177/1468794119880746.

Burholt, V., & Dobbs, C. 2014. “A Support Network Typology for Application in Older Populations with a Preponderance of Multigenerational Households.” Ageing and Society 34 (7): 1142–69. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X12001511.

Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. 2021. “About Homelessness: Causes of Homelessness.” Assessed on 5 August 2021. https://www.homelesshub.ca/about-homelessness/homelessness-101/causes-homelessness

Canham, S. L., Battersby, L., Fang, M. L., Wada, M., Barnes, R., & Sixsmith, A. 2018. “Senior Services that Support Housing First in Metro Vancouver.” Journal of Gernotological Social Work 61 (1): 104-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2017.1391919.

Ciobanu, R. O., Fokkema, T., & Nedelcu, M. 2017. “Aging as a Migrant: Vulnerabilities, Agency and Policy Implications.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (2): 164–81. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2016.1238903.

Dolberg P., Sigurðardóttir, S. H., & Trummer, U. 2018. “Ageism and Older Immigrants.” Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism 19: 177–91. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8_12.

Fajardo-Bullón, F., Esnaola, I., Anderson, I., & Benjaminsen, L. 2019. “Homelessness and Self-Rated Health: Evidence from a National Survey of Homeless People in Spain.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 1081–81. doi:/10.1186/s12889-019-7380-2.

Gaetz, S., Barr, C., Friesen, A., Harris, B., Hill, C., Kovacs-Burns, K., Pauly, B., Pearce, B., Turner, A., & Marsolais, A. 2012. “Canadian Definition of Homelessness.” Toronto: Canadian Observatory Press. Accessed on September 3, 2021. https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/COHhomelessdefinition.pdf

Gaetz, S., Donaldson, J., Richter, T., & Gulliver, T. 2013. “The State of Homelessness in Canada 2013.” The Homeless Hub. Assessed 5 August 2021. https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/SOHC2103.pdf

Garibaldi, B., Conde-Martel, A., & P O’Toole, T. 2005. “Self-Reported Comorbidities, Perceived Needs, and Sources for Usual Care for Older and Younger Homeless Adults.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 20 (8): 726–30. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0142.x

Gee, E. M., Kobayashi, K. M., & Prus, S. G. 2004. “Examining the Healthy Immigrant Effect in Mid- to Later Life: Findings from the Canadian Community Health Survey.” Canadian Journal on Aging 23 (5): 55–63.

Giannini, A. 2017. “An Intersectional Approach to Homelessness: Discrimination and Criminalization.” Marquette Benefits and Social Welfare Law Review 19 (1): 27–42.

Gonyea, J. G., Mills-Dick, K., & Bachman, S. S. 2010. “The Complexities of Elder Homelessness, a Shifting Political Landscape and Emerging Community Responses.” Journal of Gerontological Social Work 53 (7): 575–90. doi:10.1080/01634372.2010.510169.

Government of Canada. 2017. “Who’s at Risk and What Can Be Done About It? A Review of the Literature on the Social Isolation of Different Groups of Seniors.” Last updated 26 April 2017. https://www.canada.ca/en/national-seniors-council/programs/publications-reports/2017/review-social-isolation-seniors.html#h2.6-h3.3)

Government of Canada. 2021. “Social Isolation of Seniors: A Focus on New Immigrant and Refugee Seniors in Canada.” Accessed 18 August 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/seniors/forum/social-isolation-immigrant-refugee.html

Government of Canada. 2021. “The National Shelter Study — Emergency Shelter Use in Canada 2005 to 2016.” Accessed 18 August 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/homelessness/publications-bulletins/national-shelter-study.html

Grenier, A., Barken, R., Sussman, T., Rothwell, D., Bourgeois-Guérin, V., & Lavoie, J.-P. 2016. “A Literature Review of Homelessness and Aging: Suggestions for a Policy and Practice-Relevant Research.” Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement 35 (1): 28–41. doi:10.1017/S0714980815000616.

Grenier, A., Sussman, T., Barken, R., Bourgeois-Guérin, V., & Rothwell, D. 2016. “‘Growing Old’ in Shelters and ‘On the Street’: Experiences of Older Homeless People.” Journal of Gerontological Social Work 59(6): 458–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2016.1235067.

Gubernskaya, Z., & Tang, Z. 2017. “Just Like in Their Home Country? A Multinational Perspective on Living Arrangements of Older Immigrants in The United States.” Demography 54: 1973–98. doi: 10.1007/s13524-017-0604-0.

Guruge, S., Sidani, S., Man, G., Matsuoka, A., Kanthasamy, P., & Leung, E. 2021. “Elder Abuse Risk Factors: Perceptions Among Older Chinese, Korean, Punjabi, and Tamil Immigrants in Toronto.” Journal of Migration Health 4. 100059. doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100059.

Guruge, S., Birpreet B., & Samuels-Dennis, J. A. 2015. “Health Status and Health Determinants of Older Immigrant Women in Canada: A Scoping Review.” Journal of Aging Research. doi: 10.1155/2015/393761.

Haan, M. 2011. “Does Immigrant Residential Crowding Reflect Hidden Homelessness?” Canadian Studies in Population 38 (1–2): 43–59. https://doi.org/10.25336/P6331B.

Hacker, J. S., & Rehm, P. 2020. “Reducing Risk as Well as Inequality: Assessing the Welfare State’s Insurance Effects.” British Journal of Political Science First View: 1–11 doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000034.

Hossen, A., & Westhues, A. 2013. “Bangladeshi Elderly Immigrants in Southern Ontario: Perspectives on Family Roles and Intergenerational Relations.” Journal of International Social Issues 2 (1): 1–15.

Hwang, S. W., Kirst, M. J., Chiu, S., Tolomiczenko, G., Kiss, A., Cowan, L., & Levinson, W. 2009. “Multidimensional Social Support and the Health of Homeless Individuals.” Journal of Urban Health 86 (5): 791–803. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9388-x.

Ichou, M., & Wallace, M. 2019. “The Healthy Immigrant Effect: The Role of Educational Selectivity in the Good Health of Migrants.” Demographic Research 40 (4): 61–94. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2019.40.4.

Kei, W., Seidel, M.-D. L., Ma, D., & Houshmand, M. 2019. “Results from the 2016 Census: Examining the Effect of Public Pension Benefits on the Low Income of Senior mmigrants.” Assessed 11 August 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2019001/article/00017-eng.htm

Kim, B. J., Auh, E., Lee, Y. J., & Ahn, J. 2013. “The Impact of Social Capital on Depression Among Older Chinese and Korean Immigrants: Similarities and Differences.” Aging and Mental Health 17 (7): 844–52. doi:10.1080/13607863.2013.805399.

Kim, M. M., Ford, J. D., Howard, D. L., & Bradford, D. W. 2010. “Assessing Trauma, Substance Abuse, and Mental Health in a Sample of Homeless Men.” Health and Social Work 35 (1): 39–48. doi:10.1093/hsw/35.1.39.

Kushel, Mt. 2020. “Homelessness Among Older Adults: An Emerging Crisis.” Generations Summer 2020. Assessed 19 August 2021. https://generations.asaging.org/homelessness-older-adults-poverty-health

Luhtanen, E. 2009. “Including Immigrant and Refugee Seniors in Public Policy.” A discussion paper for the Calgary Immigrant Seniors “Speak Out” Forum. Assessed 1 September 2021. https://www.calgary.ca/csps/cns/seniors/speak-out-forum.html

Magesan, A. 2017. “New Fingures Show Just How Big Canada’s Immigrant Wage Gap Is.” MacLean’s. Assessed 5 August 2021. https://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/new-figures-show-just-how-big-canadas-immigrant-wage-gap-is/

McDonald, L. 2010. “Theorizing about Aging and Immigration.” In Diversity and Aging Among Immigrant Seniors in Canada: Changing Faces and Greying Temples, edited by Douglas, Durst and Michael MacLean, 59–78. Calgary: Detselig Enterprises Ltd.

McDonald, L., Dergal, J., & Cleghorn, L. 2007. “Living on the Margins.” Journal of Gerontological Social Work 49 (1–2): 19–46. doi.:10.1300/J083v49n01_02

Ng, E. 2021. “COVID-19 Deaths Among Immigrants: Evidence from the Early Months of the Pandemic.” StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Accessed 10 September 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00017-eng.pdf?st=xALpsQO4

Ng, C. F., & Northcott, H. C. 2015. “Living Arrangements and Loneliness of South Asian Immigrant Seniors in Edmonton, Canada.” Ageing and Society 35 (3): 552–75. doi:10.1017/S0144686X13000913.

Older Adult Council of Calgary. 2018. “Older Adults and Homelessness.” Assessed 27 August 2021. https://www.calgary.ca/content/dam/www/csps/cns/documents/seniors/older-adults-and-homelessness.pdf

Perri, M., Dosani, N., & Hwang, S. W. 2020. “Covid-19 and People Experiencing Homelessness: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies.” Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ). 192 (26): 716–19. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200834.

Picot, G., & Lu, Y. 2017. “Chronic Low Income Among Immigrants in Canada and its Communities.” Statistics Canada: Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2017397-eng.htm

Ploeg, J., Hayward, L., Woodward, C., & Johnston, R. 2008. “A Case Study of a Canadian Homelessness Intervention Programme for Elderly People.” Health and Social Care in the Community 16 (6): 593–605. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00783.x.

Preston, V., Murdie, R., D’Addario, S., Sibanda, P., Murnaghan, A. M., Logan, J., & Ahn, M. H. 2011. “Precarious Housing and Hidden Homelessness Among Refugees, Asylum Seekers, and Immigrants in the Toronto Metropolitan Area.” CERIS Working Paper no. 87. Assessed 1 2021. https://refugeeresearch.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Preston-et-al-2011-Precarious-housing-for-newcomers-in-Toronto.pdf

Pruegger, V. J., & Tanasescu, A. 2007. “Housing Issues of Immigrants and Refugees in Calgary.” Assessed 27 August 2021. https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/r5qrpj1a.pdf

Reynolds, C. 2019. “Immigrant Wage Gap Costing Canada $50 Billion a Year in GDP: Report.” The Globe and Mail, 17 September. Assessed 5 August2021. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-immigrant-wage-gap-costing-canada-50-billion-a-year-in-gdp-report/

Reynolds, K. A., Isaak, C. A., DeBoer, T., Medved, M,, Distasio, J., Katz, L. Y., & Sareen, J. 2016. “Aging and Homelessness in a Canadian Context.” Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health 35 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2015-016.

Rota-Bartelink, A., & Lipmann, B. 2007. “Causes of Homelessness Among Older People in Melbourne, Australia.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 31 (3): 252–58. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2007.00057.x.

Seegert, L. 2016. “Homeless Get ‘Older’ at Younger Ages than their Peers, Research Says.” Association of Health Care Journalists. Assessed 27 August 2021. https://healthjournalism.org/blog/2016/04/homeless-get-older-at-younger-ages-than-their-peers-research-says/

Setia, M. S., Quesnel-Vallee, A., Abrahamowicz, M., Tousignant, P., & Lynch, J. 2012 “Different Outcomes for Different Health Measures in Immigrants: Evidence from a Longitudinal Analysis of the National Population Health Survey (1994–2006).” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 14 (1): 156–65.

Stafford, A., & Wood, L. 2017. “Tackling Health Disparities for People Who Are Homeless? Start with Social Determinants.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14 (12): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121535.

Statistics Canada. 2017a. “Census in Brief: Linguistic Integration of Immigrants and Official Language Populations in Canada.” Accessed 5 August 2021. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016017/98-200-x2016017-eng.cfm

Statistics Canada. 2017b. “Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity: Key Results from the 2016 Census.” Last updated 1 November 2017. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-eng.htm?indid=14428-1&indgeo=0

Statistics Canada. 2020. “Demographic Estimates by Age and Sex, Provinces and Territories.” Last updated on 2 December 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-607-x/71-607-x2020018-eng.htm

Stewart, M., Shizha, E., Makwarimba, E., Spitzer, D., Khalema, E. N., & Nsaliwa, C. D. 2011. “Challenges and Barriers to Services for Immigrant Seniors in Canada: “You Are Among Others but You Feel Alone.” International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 7 (1): 16–32. doi: 10.1108/17479891111176278.

The World Bank. “Life Expectancy at Birth, Total (Years)— Canada.” Accessed 11 September 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=CA

Torres, S. 2006. “Elderly Immigrants in Sweden: ‘Otherness’ Under Construction.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 32 (8): 1341–58. doi: 10.1080/13691830600928730.

Trypuc, B., & Robinson, J. 2009. “Homeless in Canada: A Funder’s Primer in Understanding the Tragedy on Canada’s Streets.” Charity Intelligence Canada. Accessed 10 September 2021. http://www.charityintelligence.ca/images/Ci-Homeless-in-Canada.pdf

Um, S. G., & Lightman, N. 2017. “Seniors’ Health in the GTA: How Immigration, Language, and Racialization Impact Seniors’ Health.” Wellesley Institute: Advancing Urban Health. Assessed 1 September 2021. https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Seniors-Health-in-the-GTA-Final.pdf

Wilkes, R., & Wu, C. 2019. “Immigration, Discrimination, and Trust: A Simply Complex Relationship.” Frontiers in Sociology 4: 32–32. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2019.00032.

Woolrych, R., Gibson, N., Sixsmith, J., & Sixsmith, A. 2015. ““No Home, No Place”: Addressing the Complexity of Homelessness in Old Age Through Community Dialogue.” Journal of Housing for the Elderly 29 (3): 233–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2015.1055024.

World Health Organization. 2021. “Social Determinants of Health.” Accessed 3 September 2021. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1