Section 3: Socioeconomic Considerations

Chapter 6. Loneliness Kills: Social Support and Social Interactions as Determinants of Aging Well and Inclusion Among Arabic- and Spanish-Speaking Senior Immigrants in Ottawa

Paola Ortiz Loaiza; Denise L. Spitzer; and Radamis Zaky

The most important thing is that when the person gets older – don’t live alone. Loneliness kills whether you are a man or a woman. The person shouldn’t be alone; the person should have company. The type of company doesn’t matter – a spouse, a daughter, a brother. Each one should have company in order to age well.

Arabic-speaking older immigrant―

Social supports and social networks are critical to health and wellbeing (Stewart et al. 2008), but research has confirmed that for immigrants, familial and other social networks are segmented – if not severed – across borders (Spitzer et al. 2003). Migration to countries including as Canada may necessitate changes in support-seeking strategies. Older immigrants facing barriers accessing social support, whether formal or informal, can become lonely and excluded. The United Nations defines poverty as a “denial of choices and opportunities, a violation of human dignity” (UN Statement, 1998), expanding the definition from simply economic deprivation to incorporate the concept of exclusion. Fischer (2011) found that individuals can be excluded on the basis of factors including socioeconomic class, racialized status, age, and gender. The following discussion explores social interactions and social supports among older immigrants in Ottawa, the challenges and barriers they face to overcome isolation and exclusion, and how they negotiate changing needs and create resilience strategies, and – when possible – generate new networks and sources of support in their new location.

Context

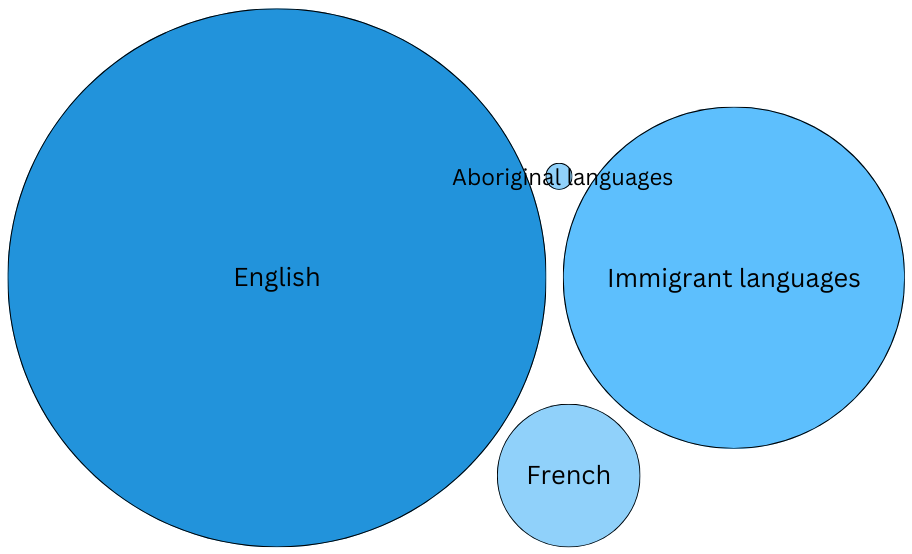

Ottawa is Canada’s national capital and has a population of approximately one million, about 23 percent of whom are foreign born (Statistics Canada, 2021). Nearly 10 percent of the foreign-born population immigrated at age 45 or older. According to Statistics Canada, 1.5 percent of Ottawa’s population speak neither English nor French (2021) – immigration laws exempt adults aged 55 and older from any language requirements and compliance with “Canadian Language Benchmarks” to immigrate to Canada and obtain citizenship (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2021). Census results from 2016 reveal that 32,295 Ottawa residents spoke Arabic as their first language (45 percent of whom were women), while 11,985 had Spanish as a mother tongue (55 percent of whom were women): these two groups represent 3.7 and 1.3 percent of the local population, respectively (Statistics Canada, 2021). These two linguistic groups are among the three largest language communities in Ottawa, after Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese) (Statistics Canada, 2021).

Figure 6.1. Ontario: Immigrant Languages and Official Languages

Source: Census 2016, Proportion of mother tongue responses for various regions in Canada

Social Support as a Determinant of Health

Traditionally, social support has been framed as a coping resource – a “social ‘fund’ from which people may draw when handling stressors” (Thoits, 1995, 64). Social supports can be broadly categorized as: emotional (e.g., empathy, humour, social activities), instrumental (e.g., services, financial and material aid), informational (e.g., knowledge), and affirmational (e.g., positive feedback, praise) (Fingeld-Connett, 2005; Makwarimba et al. 2010; Stewart et al. 2008; Wu & Hart, 2002). Social supports can be embedded in social relations, networks, and the roles that individuals enact (Thoits, 1995). Fingeld-Connett noted that social support “is an advocative interpersonal process that is centred on the reciprocal exchange of information and is context specific” (2005, 5). Here, context refers to the social and cultural environment in which meanings, shape, and expectations of social support are produced. The ways that migrants – for the purposes of this discussion, defined as all foreign-born persons – and other members of ethnic minority communities conceptualize social supports may be affected by their experiences in their respective homelands. For example, Somali refugees in Canada generally have an expansive definition of social support that emphasizes reciprocity and interdependence, which differs from the focus on formal support services promoted in Canada (Stewart et al. 2008).

Social supports have positive effects on health and wellbeing. Research has confirmed that emotional and affirmational supports mitigate the negative effects of stressors and foster coping strategies and healthy behaviours (Makwarimba et al. 2010; Stewart et al. 2008; Thoits, 1995). Conversely, chronic poor health status may result in reduced social interaction and subsequently less access to social supports (Wu & Hart, 2002). When support needs and expectations are not met, social isolation can follow (Stewart et al. 2008).

Globally, older immigrants find their social networks truncated, which increases vulnerability to social isolation (Johnson et al. 2018). Loneliness and social isolation are major challenges for this sector of the population, particularly for women and racialized minorities – even those who have resided in Canada since youth (De Jong Gierveld, Van der Pas, & Keating, 2015; Salma & Salami, 2020; Salma et al. 2018). Health problems and low income are also associated with social isolation and loneliness (Salma & Salami, 2020). Deskilling and lack of recognition of foreign credentials and work experience is common for non-European migrants, resulting in a disproportionate concentration of immigrants with lower socioeconomic status (Voyer, 2004). These patterns reflect trends in health status, with racialized (non-European) immigrant women reporting poorer health than their European and Canadian-born counterparts (De Jong Gierveld, Van der Pas, & Keating, 2015).

Social isolation and loneliness have been associated with a variety of health problems including coronary heart disease, dementia, depression, poor nutrition, and increased risk of unhealthy behaviours and mortality (De Jong Gierveld, Van der Pas, & Keating, 2015; Johnson et al. 2018). Conversely, social supports – in the form of engagement in social activities with friends and community and financial assistance (if required) – can help older immigrant women mitigate the effects of chronic illness and other stressors (Salma et al. 2018; Salma & Salami, 2020).

Socio-Political Inclusion and Exclusion

Few studies have explored social supports and connections as they relate to social and political exclusion. Social supports (formal and informal) are especially important when older immigrants face barriers related to language, access to information and technology, and mobility. For example, language and sociocultural barriers affect accessibility, safety, and quality of healthcare services, including psychiatric, physiotherapeutic , and urgent care among others (Bowen, 2015; De Moissac et al. 2020; Ohtani et al. 2015; Yoshikawa et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2019). Lack of information, including challenges in accessing and/or hesitancy in using technology and services, can also lead to exclusion from healthcare and other supportive programs (Holgersson et al. 2021). Limited mobility (including limited access to public or private transport) contributes to isolation and poverty (Engels & Liu, 2011). Social connections and both formal and informal networks are fundamental channels for older immigrants to receive information and mediation to access services and opportunities that they cannot obtain on their own.

Social exclusion can be defined as “the lack or denial of resources, rights, goods and services and the inability to participate in the normal relationships and activities available to the majority of people in a society” (Levitas et al. 2007, 9). Social inclusion implies acceptable access to resources, participation, and quality of life; all of these can be related to class, racialized status, gender, and language. According to Bernt and Colini, scholars generally agree that exclusion can be defined as “both a process and condition, one resulting from a combination of intertwined forms of social, economic and power inequalities and leading to disadvantage, relegation and the systematic denial of individuals’ or communities’ rights, opportunities and resources” (2013, 6). Exclusion is also framed as failure of the capitalist system or the market (Brenner & Theodore, 2005; Cox, 1997) in terms of redistributing wealth and welfare (see Piketty, 2014) and thereby creating uneven development through interdependent geographies (global, national, regional, urban, and micro local levels) (Bernt & Colini, 2013; Swyngedouw, 1997). Despite the various definitions used, inclusion and exclusion are complex processes with relational natures; for example, social and political exclusions are closely linked with economic factors.

Silver (1994) analyzed exclusions based on three paradigms (republicanism/solidarity, liberalism/specialization, and social democracy/monopoly) and proposed that within a solidarity paradigm, exclusion refers to the rupture of social ties – and the state has a fundamental role in providing assistance to repair the lack of social support. In the monopoly paradigm, exclusion results from the interplay of “class, status and political power” between the excluded and the included – serving the interests of the included. In this case, inclusion would occur through granting “formal rights such as citizenship and extension of membership” by the dominant group (see Bernt & Collini, 2013, 7) ― emphasizing political inclusion.

The following discussion presents some of our findings from our work with Arabic- and Spanish-speaking older immigrants in Ottawa, which was informed by the following assumptions: (1) Social supports and social networks counteract isolation and their negative implications for health and wellbeing; (2) Exclusions result from lack of access (or denial) to resources, rights, goods and services ― including a paucity of or limited participation in the relationships and activities that are available to the majority of non-immigrant elders.

The Study

We explored the main causes and implications of social isolation, loneliness, and exclusion affecting the lives of older immigrants in Ottawa, as well as the main barriers they face in accessing formal and informal social support and the mechanisms they use to overcome those barriers. This work was part of a province-wide project designed to clarify informal networks (e.g., friends, family, and other social relationships) as well as formal social services (e.g., organized settlement, health, legal, and other programs) available to older immigrant immigrants in four cities. The cities were chosen for their different sizes and immigrant populations: London, Ottawa, Toronto, and Waterloo.

The research in Ottawa focused on two communities: Arabic-speaking and Spanish-speaking older immigrants. Our approach was exploratory and qualitative. Aided by a community advisory committee of representatives from cultural communities, immigrant-serving agencies, and academia, two bicultural graduate student research assistants who are fluent in Spanish and Arabic recruited participants and collected and analyzed data.[1] Participants included foreign-born Ottawa residents aged 60 or older, whose first language was Spanish or Arabic, and who had lived in Canada for less than 20 years. Family members, community leaders, and service providers also contributed, but the following discussion focuses specifically on focus groups involving foreign-born older immigrants (N = 38).

| Table 6.1 Sample and Focus Groups in Ottawa | ||||

| Older immigrants | Focus group discussions # | Men | Women | Total participants |

| Arabic | 5 | 8 | 14 | 22 |

| Spanish | 4 | 6 | 10 | 16 |

| Total | 9 | 14 | 24 | 38 |

| Family members who provide care | ||||

| Arabic | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Spanish | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 2 | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| Service Providers | ||||

| Arabic | 1 | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Spanish | 1 | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| Total | 2 | 8 | 9 | 17 |

We hosted focus group discussions using a semi-structured interview guide informed by academic and grey literature and recorded them with consent. Transcripts of focus group sessions were translated from Spanish or Arabic into English and anonymized by the research assistants who conducted them. The research team used an intersectional approach to explore similarities, differences, and nuances between and among the two language communities, considering gender, national origin, language, and economic variables. They independently coded transcripts and met regularly to reach agreement on codes and subcodes. Analyses explored social dimensions (e.g., gender, culture, meaning of aging, language, length of stay in the country, extended family co-residence); actual/preferred size and composition (gender, culture, age, location) of informal networks; and types and frequency of supports, reciprocity, expectations, conflict, and formal social support services (e.g., police, legal, employment, education, ESL, housing and transportation). After analysis at individual and group levels, data were integrated across gender and language communities to reveal common and unique themes.

Each participant also completed a comprehensive questionnaire that collected contextual information about demographics, health, living arrangements, economic situation, sense of belonging, and physical and emotional needs. These data were coded and analyzed for comparison between communities. Given the limited number of focus group participants, survey data complemented and contextualize the qualitative findings from focus groups.

We analyzed the focus group discussions involving 38 older immigrants: 22 from the Arabic-speaking community and 16 from the Spanish-speaking community. Analyses were triangulated with questionnaires, as well as comments by family members and service providers who were also interviewed in a different set of focus groups (held in Spanish, Arabic, and English).

Table 6.2 lists characteristics of the study population, including gender, age, length of stay in Canada, marital status, first official language spoken, and living arrangements.

| Table 6.2 Demographic Characteristics of Older Immigrants Interviewed | |||||||

| Category | Men Arabic-speaking | Women Arabic-speaking | Arabic Total | Men Spanish-speaking | Women Spanish-speaking | Spanish Total | Total |

| Total sample | 8 | 14 | 22 | 6 | 10 | 16 | 38 |

| Age | |||||||

| 60–65 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 13 |

| 66–70 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 7 |

| 71–75 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| 76–80 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 81–85 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 86 and older | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| N/A | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Length of stay | |||||||

| 6 to 10 years | 4 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 11 |

| 11 to 15 years | 3 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

| 16 to 20 years | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| 21 years or more | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| First official language | |||||||

| Excellent English | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Excellent French | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Very good English | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 12 |

| Some English | 3 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 9 | |

| Poor English | 1 | 6 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Poor French | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| No English/No French | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Marital status | |||||||

| Divorced | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 8 | ||

| Married | 7 | 7 | 14 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 20 |

| Separated | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Single | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Widow/widower | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 7 | |

| Living arrangements | |||||||

| Lives alone | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

| Live with mother/father (elderly) | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Daughter/son (and grandkids) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 7 | ||

| Husband/wife | 5 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 15 |

| Husband/wife and son/daughter | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |

| N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

Voices of Older Immigrants: Analyzing Data

During focus group discussions, older immigrants from both communities frequently mentioned loneliness as a major challenge, but responses varied between communities and individuals.

Loneliness and Isolation

Many participants referred to loneliness in terms of living alone, having no family nearby, and difficulties in meeting and interacting with others to create long-lasting friendships. Others referred to the challenges of adapting to a new country and a different culture. Some complained of being lonely most of the time because family members worked all day and did not have time to share, eat, and talk with them. This loneliness may be more acute when no neighbours or friends are nearby. One Arabic-speaking woman commented, “Loneliness kills. There should be more activities to increase the older immigrants’ self-esteem and activities that make older immigrants don’t feel that they are isolated and lonely. They have someone to check on them and to take care of them.” Another said:

My family lives far from me. I don’t find kindness and support and … it is very hard to deal with the doctors because of the language … We study English a lot but we forget it as elders’ memory is not good. Loneliness is the most difficult thing to any human being. Living far from the family is very hard even if your children live here. They are very busy and the day is very short here.

Some participants perceived their neighbours as distant or unapproachable, or question their own ability to interact in the new context. One Arab-speaking man commented: “My problem here is that I can’t make friends. I used to have a lot of friends in my country of origin. I have been here in Canada for four years and … I failed to make friends.” Another said:

I feel so lonely here. There is no social life here. Even here in the church people don’t socialize enough— we only see each other on Sundays and then everyone go home. Unlike Egypt, people here don’t have strong emotional connections to each other. I don’t know why. Even Canadians themselves are having the same problem.

This excerpt illustrates the challenges older immigrants face with regard to language and culture – but also their need to relate to others who understand their experiences and cultural context. One Spanish-speaking man said:

And about the world of sentiments and affections, I think this is something very important, especially for immigrant communities, because sometimes we have lived very hard things in our countries, or exile or something—we have friends who are political refugees or others with really hard life stories and to manage all that world of emotions is sometimes so hard.

He was referring not only to experiential and cultural differences, but also to mental health challenges faced by some older immigrants face, depending on their former life conditions and circumstances of migration (or expulsion) to Canada. Reasons for immigration are heterogeneous and can lead to much different social and economic circumstances.

A few Spanish-speaking older immigrants said they can enjoy their solitude and independence as long as they have health, resources, and mobility – especially if they have someone to lean on when needed. One Spanish-speaking man said:

I have a family … with many friends in Peru … there were too many people there! And here, the good thing is that here one can choose if you want to be with people or without people, or if you want to be alone! It is to say, that solitude/loneliness is not necessarily something negative. I see solitude as something positive. You have time to read, to watch the programs you want, and I see solitude as something good when you can abandon it whenever you want! And then you can go and meet someone, right? I see solitude/loneliness as something that has positive aspects and negative aspects!

Culturally Different Expectations and Needs for Social Support

Many participants felt that the culture in their country of origin was warmer and more welcoming to older individuals than Canada. This sentiment affected how they perceived their treatment by formal service providers. It also led to a sense of loss of relevance among participants in both language groups, and some noted that older persons are traditionally seen as a source of wisdom and authority in their communities but they were not valued in the same way in Canadian society. One commented:

There is a sense of loss for a lot of parents and even grandparents who used to be either matriarchs or patriarchs to the family. Losing all that power, and having to find out: “OK, what is my role here, what’s my purpose in this country?” … Especially depending on the culture you come from … we give older immigrants a lot of praise and they have such important roles there! But here in Canada it is not like that. We … put them in a home and that is enough! In our culture … when you live with your parents you take them in — you don’t put them in a home where they are going to be alone, and they feel that they’ve been left behind.

This feeling of exclusion from the structures and dominant values of Canadian society was also reflected in comments about interactions with the healthcare system. For example, one Spanish-speaking woman noted that the structure of the healthcare system and behaviour of healthcare practitioners contrasted with her expectations, and that this can contribute to the challenges faced by older immigrants when trying to access formal services.

The problem is that the physicians here … they treat us so distant. They do not treat us with that care/love, “how have you been?” at least! … Hi! And that is all, and then you have to sit down! “What is happening to you? How can I help you?” that is the word! [all laughing] “May I help you?” [phrase in English] and that is all! [the rest of the participants laugh out loud] What for will I come here, then? [emotional-angry] they just tell you and tell you … But tell me, is it like that or not?

All participants: [Different voices overlapping] yes, YES, it is like that!

The need to be heard is even more problematic for those who do not speak either of Canada’s official languages. Some participants said that this problem may be overcome with a translator or interpreter in formal services, but even these services involve challenges. For example, interpreters are often not available at the appointment site, so service providers may ask older immigrants to bring a family member to interpret for them – in many cases, this prevents older immigrants from expressing their real needs or feelings. Moreover, even when a formal interpreter is provided, older immigrants may find it difficult to express their problems to a stranger who is not a physician – while also being forced to trust that this person will explain their real needs – especially when they are trying to explain a delicate or confidential situation. One Spanish-speaking woman noted:

The same way, the social worker feels limited when she talks to us. They tell us that there are interpreters, but they are very scarce. And so, they tell you that you better bring your friend or your son, or sometimes there are five-year-old kids helping their parents, that is the biggest barrier that exists for the older people, and to age, right? One who has gotten here younger, even if he/she doesn’t speak English, he/she is able to defend his/herself and keeps moving forward.

Sense of Belonging and Autonomy

Despite all the challenges, Arabic-speaking older immigrants appear to have a stronger sense of belonging to the local community than their Spanish-speaking counterparts. All of the Arabic speakers responded that their sense of belonging to their community was strong or very strong, while only eight of the 16 Spanish speakers felt a strong or very strong belonging.

In this context, “local community” may refer to their language-speaking community or their neighbourhood or Ottawa. No specific or single variables appear to explain this sense of strong or weak belonging to the community; a complex mix of variables is at play. For example, most of the interviewed Arab-speaking older immigrants (18 out of 22) were married and/or lived with other family members, which may help explain their stronger sense of belonging to family or community.

For the Spanish-speaking community, belonging to a community referred primarily to the city of Ottawa or their own neighbourhoods, which was different from the Arabic-speaking community.

We know what Latin America is like. There is a different quality of life there, the presence of the people. Hugs flow there, it is very easy to touch and express care and love! Here we can’t—everything is prohibited, everything is harassment! The relationships are colder, and they are supposed to be like that. It is evident due to the existent ethnocentrism, right? … We are part of the few couples who do not have a family. We don’t have anybody here—no children, no siblings, no uncles, no grandkids, nothing! I am her husband, she is my wife, and there is nobody else! … Well, I do have an assimilated family which are my friends, you and you. Our friends begin to be like our family. I think that is what is missing, to migrants in general, Latinos in particular, when we come here. The huge family that we have in our countries is reduced or null.

Spanish-speaking participants also described having limited spaces and moments to interact; some women noted that accessing meetings and activities required extra effort, time, and resources. One commented:

It is easier and naturally pleasant to get older in our countries than here. And that is why I think it is so important that here exist groups like this one [organization named], because we have to, artificially … — in the best sense of the word—create support networks because in our countries that network is the neighbours from across the street, from next door!

The idea of autonomy is closely linked with the sense of belonging and feeling part of a family, network, or community, as well as other variables such as language and mobility. The research team identified several elements related to financial and family related autonomy. Relatively more Spanish-speaking participants were divorced (six of 16 were divorced or separated) compared to Arab-speaking participants (three of 22). With a single exception, all Spanish-speaking women were financially independent and had some source of income (mainly wages/salary). In contrast, only seven of 14 Arabic-speaking women reported having a source of income: Arabic-speaking women depended more on their husbands and children, were less independent, and were mostly responsible for unpaid house labour. However, the fact that most Spanish-speaking women (and men) were still depending on wages raises other questions about pensions, survival, and life quality in the elderly years. Gender and socioeconomic status were important determinants for both communities.

The data also suggest that women tend to have a stronger sense of belonging if they are married or live with their family, compared with those living alone or working to support themselves or their families. Despite having a weaker sense of belonging, Spanish-speaking women were very active organizing activities in their communities (e.g., community groups, celebrations, and meals). This reveals the importance – and also the fragility – of social networks for immigrants, who depend on close family and friends to overcome isolation and develop a sense of belonging. In general, loneliness and isolation appear to become more pronounced during the winter months when it is more difficult to organize or attend other community activities.

Well, here we have to create community, and in our countries maybe not, because there is already a community: you grew up there, you know the people, and you move around. You don’t have to create those connections. Then here if you isolate yourself and you stay alone at home, you isolate yourself and do not make those connections. Those things that over there you don’t have to look for … they are already given, because you are there, isn’t this true? Then here, if we don’t make an effort to go out and look for those connections, we isolate ourselves, and maybe because we have known each other, and we are here in this group, then we don’t feel that lonely, but there are people who… feel alone and they are not here because they have not been able to connect.

With regard to income patterns, similar patterns emerged for male older immigrants. Five of six Spanish-speaking men reported having some source of income, while only two of eight Arab-speaking men reported having any source of income. Some of the Spanish-speaking interviewees were still working (full-time, part-time, or self-employed) to support their families because they had no access to a pension. However, some participants reported having good pensions or family savings or investments. Both language communities were very heterogeneous in terms of economic situations, which varied based on education, profession, living arrangements, reasons for immigration, and length of stay in Canada. Arabic-speaking participants referred to socioeconomic challenges; one commented: “Yes, I have some obstacles, like I don’t receive pension. This is an obstacle. I transfer my pension from my home country and it is only $200. This is not enough money to live. I have to pay rent; I have to buy food, I have to buy medications.” Another said:

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any job. I also decided to take a career shift and find a job as an office manager, however, I couldn’t find a job. I am so concerned and worried not to be able to live well, even after I start to get the Old Age Pension after I become sixty-five. How much money will I get? 300 or 400? and also, I’m not sure if I will be able to get it. Even if I got it, can I live with dignity with this amount of money?

Barriers to Participation and Access to Services

In most cases, loneliness is very closely related to language, mobility, technology literacy, and economic barriers, all of which limit access to services and participation in other activities. One Spanish-speaking man said, “it is very difficult to establish a relationship with anyone while I don’t have the language.” Limited language proficiency in at least one of Canadas two official languages is one of the most fundamental barriers to full independence and wellbeing among older immigrants in Ottawa. This single variable alone is not responsible for determining sense of belonging to the community, but language proficiency affects opportunities for a range of activities and is further implicated in social inclusion or exclusion. Ability to interact with others is strongly related to independence in terms of economic resources, health, physical mobility, and ability to navigate. Literacy – including technological literacy and access to information (particularly on-line resources) – was clearly identified.

Poor health and aggravated health conditions (e.g., hearing/sight loss, mobility problems) are also significant barriers to connecting with the community and with necessary formal services. One older immigrant woman who was caring for her elderly mother noted:

Fortunately, I have a mother who is very open, very independent since youth. She has been independent and takes risks! Now she is ageing. Well, now physically her sight is preventing her from many things, but she can adapt herself. She has even adapted already — she is 88 now—she migrated to Canada at 80 years of age!

Some participants also noted that mobility was further challenged by Ottawa’s hard and long winter. One said:

Back home you can go see family, you can go do social activities, you can go visit things around. But here … they don’t really either have the time to see anyone or other people don’t have time for them … They are just sitting home doing the normal things which I feel like—after they get to the older immigrant years, they are just dying the slow death … Maybe the weather is not helping with it but at the same time I just feel like, living for them [older immigrants] in Canada is just like a locked place. They are just going to live in this house for the rest of their lives.

Conclusion

Older immigrants in Ottawa reported feeling socially excluded because of language and socioeconomic barriers and being deprived of meaningful work. They referred to challenges to physical and social mobility related to climate and declining health status. These compounding issues furthered their inability to access certain social programs. Loneliness, lack of social interaction, and a sense of lost relevance were major obstacles to aging well in Canada. Another major issue is that older immigrants –many who live alone – have been aging in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had acute effects on isolation and health. However, many older immigrants tried to overcome challenges by seeking out informal connections with members of their own cultural communities: this helped some of them overcome language barriers, remain physically and mentally active, and maintain their health and wellbeing. However, some “younger” older immigrants who are still economically active do not consider themselves older immigrants: they struggle to adapt and support themselves and their families. Overall, older immigrants in Canada face persistent challenges as they age, and much more work is required to explore how age, gender, and language are related to their wellbeing.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Based on our findings, we have developed several recommendations with implications for program, practice, and policy development. Older immigrants would benefit from the creation of safe and accessible spaces to gather and interact informally, as well as to access low-cost or free further education programs, preferably in their own languages (e.g., Spanish or Arabic), such as English as an additional language, computer training, and physical fitness. Information about these programs and registration forms should be provided in their own language, because older immigrants find it difficult to navigate in English or French. Another option is to provide more interpreters and translators.

Older immigrants also want more access to social programs including pensions, as well as linguistically and culturally compatible health and social services; female care providers in particular wanted access to care programs to support families. Many older immigrants also want opportunities to find remunerative and meaningful employment.

Although our study population included many professional and highly educated older immigrants, those who faced language and economic barriers needed extra support to access low-cost and safe transportation in their language to facilitate mobility and thus enable participation in other activities. Notably, many sought access to linguistically and culturally appropriate training and literacy programs and ways to navigate the system: how and where to ask for information in their language, how to access information online, how to find a route and map for the public transport system, and how to ask for help. Some relied on family for support, including information, but family members may not have the time or the most accurate or up-to-date information to pass along.

Overall, addressing loneliness and isolation among older immigrants will require ensuring they have access to services, activities and other members of their communities. It will also require providing economic and material support, which are both fundamental in terms of preventing unhealthy dependencies and elderly abuse. By strengthening connections with family and friends and promoting wellbeing, it will be possible to foster inclusion (belonging to a community) and mitigate social (and political) exclusion. Finally, older immigrants who are aging in a new country may have different ideas about the meaning of social support and social inclusion, so all services should be inclusive and culturally appropriate.

References

Bernt, M., & Colini, L. 2013. Exclusion, Marginalization and Peripheralization: Conceptual concerns in the study of urban inequalities, Working Paper, No. 49, Leibniz-Institut für Regionalentwicklung und Strukturplanung (IRS), Erkner. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2013052811489

Bowen, S. The Impact of Language Barriers on Patient Safety and Quality of Care. Société Santé en français; 2015.

Brenner N., & Theodore, N. 2005. Neoliberalism and the urban condition, London et.al.: Taylor & Francis.

Cox, K. R. 1997. Spaces of Globalization: Reasserting the Power of the Local, New York: Guilford Press.

De Jong Gierveld, J., Van der Pas, S., & Keating, N. 2015. “Loneliness of Older Immigrant Groups in Canada: Effects of Ethnic-Cultural Background.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 30: 251-268. DOI: 10.1007/s10823-015-9265-x.

De Moissac, D., Savard, J, Savard, S., Giasson, F., & Kubina, L.-A. 2020. Management strategies to improve French language service coordination and continuity for official language Francophone seniors in Canada. Healthcare Management Forum, 33(6), 271–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470420931115

Engels, B., & Liu, G. J. 2011. Social exclusion, location and transport disadvantage amongst non-driving seniors in a Melbourne municipality, Australia. Journal of Transport Geography. Volume 19, Issue 4, Pages 984-996, ISSN 0966-6923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.03.007.

Fingeld-Connett, D. 2005. “Clarification of Social Support.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 37(1): 4-9.

Fischer, A. 2011. ‘Reconceiving Social Exclusion’, BWPI Working Paper 146, Brooks World Poverty Institute, Manchester.

Holgersson, J., Kävrestad, J., & Nohlberg, M. 2021. “Cybersecurity and Digital Exclusion of Seniors: What Do They Fear?” Human Aspects of Information Security and Assurance, 2021, p. 12–, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-81111-2_2.

Johnson, S, Bascu, J., McIntosh, T., Jeffrey, B., & Nuelle, N. 2018. “Social Isolation and Loneliness Among Immigrant and Refugee Seniors in Canada: A Scoping Review.” International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 15(3): 177-190. DOI: 10.1108/1HMHSC-10-2018-0067.

Levitas, R., Pantazis, C., Fahmy, E., Gordon, D., Lloyd, E., & Patsios, D. 2007. The Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Social Exclusion.

Makwarimba, E., Stewart, M. J., Jones, Z., Makumbe, K., Shizha, E., & Spitzer, D. L. 2010. “Senior Immigrants’ Support Needs and Preferences of Support Intervention Programs.” In Diversity in Aging Among Immigrant Seniors in Canada, edited by D. Durst and M. Maclean, pp. 205-226. Calgary: Detselig Enterprises, Ltd.

Ohtani, A, Suzuki, T., Takeuchi, H., & Uchida, H. 2015. Language barriers and access to psychiatric care: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 66(8):798–805.

Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Salma, J., & Salami, B. 2020. “‘Growing Old is Not for the Weak of Heart’: Social Isolation and Loneliness in Muslim Immigrant Older Adults in Canada.” Health and Social Care in the Community 28: 615-623. DOI: 10.1111/hsc.12894.

Salma, J., Keating, N., Ogilvie, L., & Hunter, K. 2018. “Social Dimensions of Health Across the Life Course: Narratives of Arab Immigrant Women Ageing in Canada.” Nursing Inquiry 25 (e12226): 1-8. DOI: 10.1111/nin.12226.

Silver, H. 1994. Social Exclusion and Social Solidarity: Three Paradigms’, In: International Labour Review, Vol. 133. 5-6, 531-578.

Spitzer, D. L., Neufeld, A., Harrison, M., Hughes, K., & Stewart, M. J. 2003. “Caregiving in Transnational Perspective: ‘My Wings Have Been Cut, Where Can I Fly’” Gender & Society 17(2): 267-286.

Statistics Canada. 2021. Census Profile, 2016 Census. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&TABID=1&B1=All&type=0&Code1=3506008&SearchText=ottawa Accessed 3 September 2021.

Stewart, M. J., Anderson, J., Makwarimba, E., Neufeld, A, Simich, L, & Spitzer, D. L. 2008. “Multicultural Meanings of Social Support Among Immigrants and Refugees.” International Migration 46(3): 123-159.

Swyngedouw, E. 1997. Neither global nor local: ‘glocalization’and the politics of scale, New York: Guilford Press.

Thoits, P. 1995. “Stress, Coping and Social Support Processes: Where Are We? What Next?” Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 35(extra): 53-79.

UN. 1998. United Nations Economic and Social Council. Statement of commitment for action to eradicate poverty adopted by administrative committee on coordination.

Voyer, J.-P. 2004. “Foreward.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 5(2): 159-164.

Wu, Z., & Hart, R. 2002. “Social and Health Factors Associated with Support Among Elderly Immigrants in Canada.” Research on Aging 4: 391-412.

Yoshikawaa, K, Brady, B., Perry, M. A., & Devand, H. 2020. Sociocultural factors influencing physiotherapy managementin culturally and linguistically diverse people with persistentpain: a scoping review. Physiotherapy 107, 292–305.

Zhao, Y, Segalowitz, N., Voloshyn, A., Chamoux, E., Ryder, A. G. 2019. Language barriers to healthcare for linguistic minorities: the case of second language-specific health communication anxiety. Health Community 1–13. doi:10.1080/10410236.2019.16924.

- We especially thank the Latin American Women’s Organization (LAZO), Immigrant Women’s Services Ottawa/ Services pour femmes immigrantes d’Ottawa, Club Casa de los Abuelos, Ottawa Local Immigration Partnership / Partenariat Local d’immigration d’Ottawa, and Dr. Martine Lagacé for their valuable support and advice. ↵