Critical Indigenous Perspectives on the Sociology of Education

Chapter 2: Theories in the Sociology of Education

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Understand what is meant by macrosocial, microsocial, mesosocial, and middle-range theory.

- Explain how agency, structure, ontology, and epistemology are related to major underlying assumptions within sociological theories of education.

- Describe how feminist theory is connected to the sociology of education.

- Explain critical race theory and how it is related to the sociology of education.

- Explain Marxism and neo-Marxism, and name the major theorists associated with these perspectives.

- Explain how critical pedagogy is associated with the Marxist perspectives.

- Define what is meant by cultural reproduction theory and identify major theorists associated with this orientation.

- Explain what is meant by social capital.

- Describe the social mobility approaches to the sociology of education.

- Define ecological systems theory.

Introduction

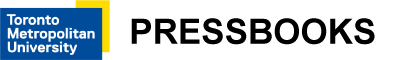

This chapter introduces several theories concerning the sociology of education. Because this text explores education from a sociological perspective, it is essential that we consider how theory contributes to our understanding of education as a part of society. Sociological theories help us to assemble diverse views about society and then construct or constitute a more comprehensive understanding of what is happening and why. Each theoretical perspective represents a particular way of understanding the social world. It is like seeing the world through a specific set of glasses (see Figure 2.1). The way we see the world clearly influences how we interpret the social processes that are occurring within it. In this chapter, theories are presented chronologically as they have developed over time.

Many theories are given consideration in this chapter. No one theory is “right”—you will see that every theory has its own strengths and weaknesses. All theories focus on different aspects of human society; some focus on class, others on race, others on gender. There is much overlap, and while many theorists talk about class, for example, you will find that they think of it in markedly different ways. And the prominence of particular theoretical perspectives follows definite trends. Some of these theories were very popular in the discipline at one point (e.g., structural functionalism) but are barely considered now. However, it is important to understand the origins of all theories of educational sociology in use today. Understanding the era of a theory—that is, the historical circumstances under which it emerged—often also helps to understand the emphasis given to different aspects of social life.

Each theory is presented with a brief overview followed by examples from recent research, including Canadian research where possible. This chapter is meant to be a synopsis of the various theories used by sociologists of education; it is in no way an exhaustive overview of all theories within the discipline.

Terminology

When you are learning about sociological theories, you may run across numerous words that you have not encountered before. Various theories are peppered with strange terminology. Theorists have adopted the use of specialized words to capture concepts that often have very complex meanings. Below, many such instances of these terms are discussed: cultural capital, habitus, racialization, and primary effects, just to name a few. Many of these terms are specific to one particular body of theories or a particular theorist.

Some terms, however, are used throughout the discussion of theory rather frequently. These terms are macrosocial theory, microsocial theory, agency, and structure.

Agency and Structure

What is more important in explaining social life—individuals or the social structures around them? This is the question at the heart of the debate between agency and structure. refers to the individual’s ability to act and make independent choices, while refers to aspects of the social landscape that appear to limit or influence the choices made by individuals. So, which one takes primacy—individual autonomy or socialization? Of course, this question is not easily resolved and it is central to theoretical approaches in sociology. Some theorists emphasize the importance of individual experience, therefore favouring agency. Those theorists who favour agency are associated with microsociological explanations of social phenomena. Other theorists view society as a large functional organism. These are macrosociologists, who see the social world as a series of structures with varying degrees of harmony.

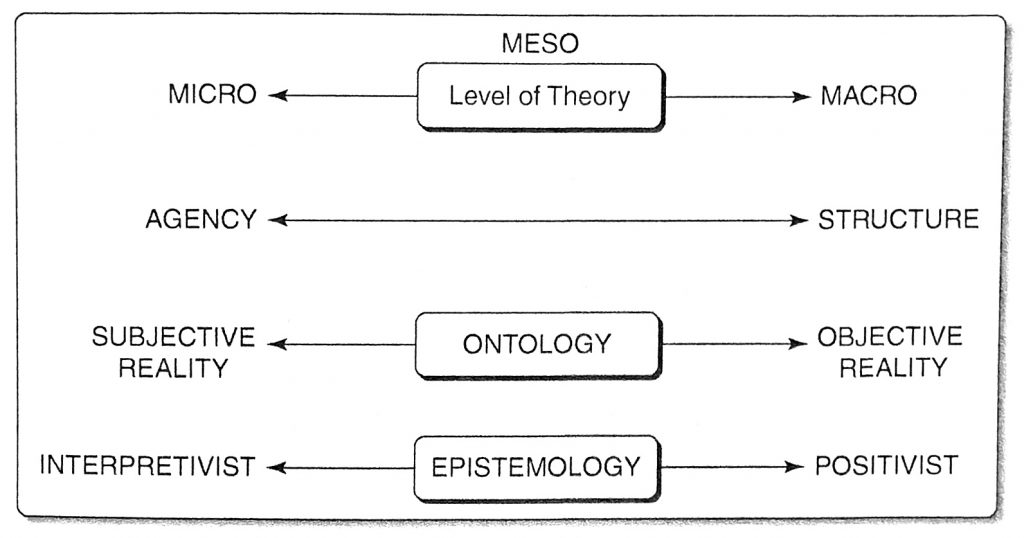

The agency–structure debate in social theory isn’t simply about which is more important; it also considers what it is that ties the individual to society. Society is more than a collection of individuals—there is something larger at work that makes those individuals a “society.” The Marxists (i.e., macro theorists) emphasize how social structures determine social life and maintain that individual actions can be reinterpreted as the outcomes of structural forces. In other words, it may seem that individuals made decisions to act in certain ways (e.g., get a specific job or take a specific course) and these theorists would argue that the larger forces of society and structure constrain an individual’s choices in such a way that these are the only decisions that can be made. Phenomenologists are microsociological theorists who focus on the subjective meanings of social life and how these meanings are responsible for creating individuals’ social worlds. Much research in social theory has focused on how to reconcile the structure and agency debate by exploring how individuals are connected to society. Some reconciliations are offered by Berger and Luckmann (1969), Giddens (1984), Ritzer (2000), and Bourdieu (1986). Bourdieu’s concept of the habitus as a bridge between structure and agency will be discussed later in this chapter. Similarly, Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) discussion of the various ways and levels at which the child interacts with the environment will also be a considered as way of bridging the gap between agency and structure.

Ontology and Epistemology

Also underlying theoretical perspectives are other assumptions about the social world. There are two very important assumptions to consider when thinking about theories in the sociology of education—ontology and epistemology.

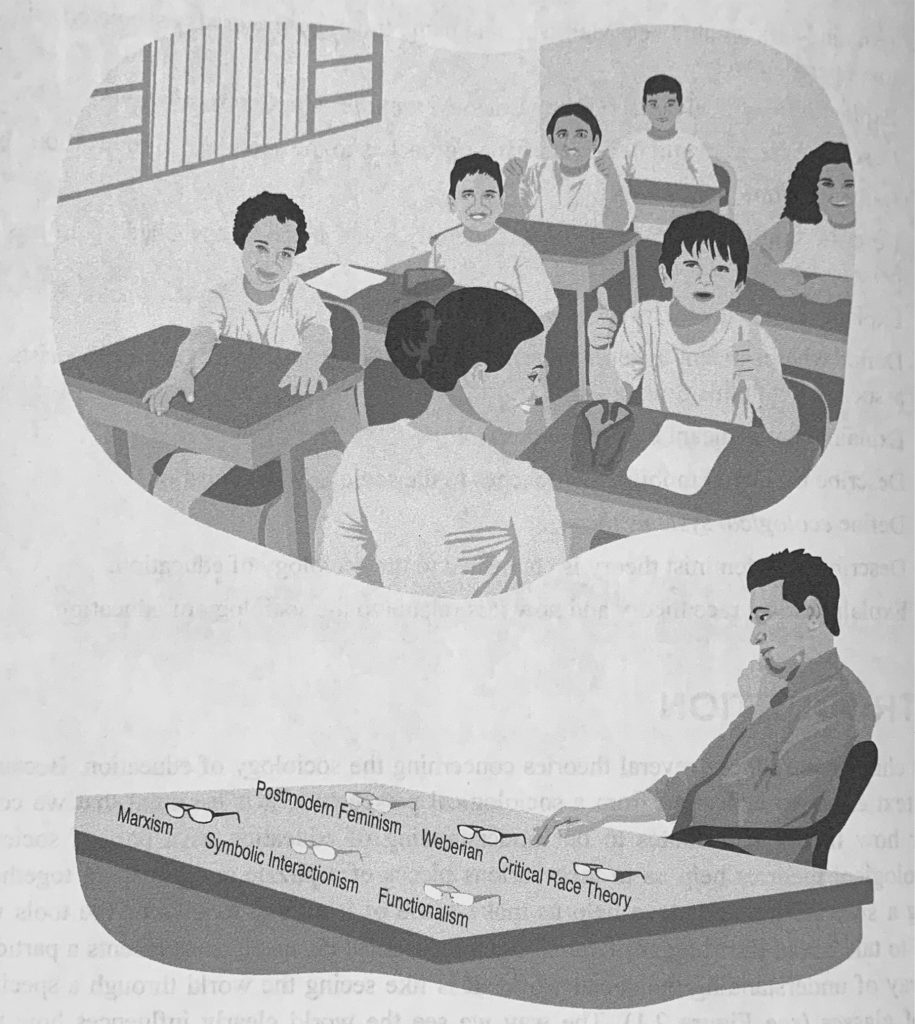

The theoretical perspectives considered in this text all have “taken-for-granted” ontological and epistemological orientations in their worldviews. Figure 2.2 graphically illustrates how ontology, epistemology, agency, structure, and the levels of social theory tend to correspond to each other on a spectrum. Microsocial theorists, for example, tend to emphasize agency over structure, point to the importance of understanding subjective reality, and use interpretive methods (in-depth qualitative interviews) when undertaking their studies. On the opposite end of the spectrum are macrosocial theorists, who focus on structure and believe in an objective reality that is to be learned about through positivist methods.

When learning about theories, it is important to think about what the theorist is assuming about social life. Theorists approach their subject with specific orientations to the primacy of agency or structure, micro/macro sociological concerns, and specific beliefs about the nature of reality and how it should be studied. There are stark distinctions among theoretical approaches and recognizing the assumptions made by theorists in this way can help you understand the major differences in the “schools of thought” explored in the rest of the chapter.

Feminist Approaches

Feminist theory within the sociology of education is concerned with how gender produces differences in education, whether it concerns access to education, treatment in the classroom, achievement, or learning processes. Feminist theory and feminism in general has undergone tremendous shifts since its beginning in the late nineteenth century compared to how it is popularly understood in academic research today. There are three general “waves” that are associated with feminism (Gaskell 2009). First wave feminism is associated with the women’s rights and suffrage movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The concern of feminists of this generation was to achieve equal rights to men.

Second wave feminism, which occurred in the 1960s and extended into the early 1990s, focused on women’s equality, financial independence, women’s access to work, and sexual harassment. An important theoretical orientation that developed during this time period was standpoint theory, which is associated with the work of prominent Canadian sociologist Dorothy Smith. Among her contributions to sociology, Smith is known for , which calls for a sociology from the standpoint of women. Standpoint theory focuses on the settings, social relations, and activities of women that are their own lived realities. Unlike other feminist approaches that emphasize how sex roles shape the domination of women, standpoint theory focuses on how knowledge plays a central role in social domination of women and how a dearth of women’s voices in the construction of this knowledge contributes to oppression. In Mothering for Schooling, Griffith and Smith (2005) used a similar approach to show how mothers’ work in getting children ready for school, volunteering at schools, and helping with homework is necessary for the school system to function, but it also serves to hinder women in working for income. The authors show how this gendered labour is closely tied to the success or failure of children at school and how the school system depends on this invisible and uncompensated labour.

Having emerged in the early 1990s, third wave feminism is what is most commonly (but not exclusively) associated with feminist approaches in research today. Also known as critical feminism, third wave feminism is largely a response to the White middle-class focus of second wave feminism. Not only concerned with gender, third wave feminist scholarship also focuses on the intersection of race and class in producing inequality.

Box 2.7 – Examples of How Feminist Researchers Approach the Sociology of Education

Zine (2008) uses a feminist approach to study identity among Muslim girls at an Islamic school in Toronto. She notes how these girls construct a gendered and religious identity “within and against the dominant patriarchal discourses promoted in Islamic schools” (p. 35). Zine examines how the girls’ identities have been shaped by resisting the dominant Islamophobic discourses prevalent in mainstream society as well as the patriarchal discourses in parts of the Muslim community. The author highlights how these girls have multiple discourses of oppression that they resist when forming their identities.

Currie, Kelly, and Pomerantz (2007) studied teenage girls at a high school in Vancouver to illustrate how a discourse of “meanness” was used to maintain covert forms of power. Teenage girls reported how popularity was maintained through the use of relational aggression, which refers to subtle forms of aggression that are couched in “mean” gossip creation, “backstabbing,” being given the “silent treatment,” and being ridiculed and called names. The authors found that the girls described myriad unspoken rules about what constituted the right type of femininity, which involved interactions with boys and manners of dress. The authors stressed that this type of aggression is usually absent from discussion of girls’ aggression because it embedded in girls’ identities and is often invisible to teachers.

Often dubbed , the critical feminist scholarship of third wave feminism frequently scrutinizes the meaning surrounding gender and how power relations play themselves out in subtle ways. The work included under critical feminist or postmodern studies in the sociology of education is incredibly varied. There is no single theory or theorist that can be associated with this perspective. Other feminist scholars (Dillabough and Acker 2008; McNay 2000) have adapted the work of major theorists, such as Bourdieu, so that they are more overtly focused on issues of gender. Many self-identified postmodern feminists draw on the work of Michel Foucault, a theorist associated with discourse analysis (and poststructuralism). Discourse refers to the way that a certain topic is talked about—the words, images, and emotions that are used when talking about something. Postmodern feminists who use a Foucauldian approach would be interested in examining how language is used to maintain gendered power relationships. Many critical feminist scholars draw upon the work of several theorists to fine-tune their particular theoretical orientation. Box 2.7 provides some examples of some recent Canadian critical feminist scholarship in the sociology of education.

Indigenous feminists examine how colonial violence constitutes racist and sexist actions towards Indigenous girls, women, and two-spirited people. It is difficult to identify just one thread of Indigenous feminist ideology, so commonly feminisms are plural. Indigenous feminisms also make vital connections between the extractivist industries, man camps, and violence towards Indigenous girls, women, and two-spirited people. For more information about Indigenous Feminisms, visit the Canadian Encycopedia definition and consider this extensive reading list.

Critical Race Theory

As suggested by the name, critical race theories put race at the centre of analysis, particularly when analyzing educational disadvantage. has its roots in legal scholarship from the United States. Examination of the racialized nature of the law has been extended to examine how race is embedded in various aspects of social life, including education (Ladson-Billings and Tate 1995; Tate 1997). Critical race theorists assert that inequalities experienced in education cannot be explained solely by theories of class or gender—that it is also race and the experience of being racialized that contributes to stratification of many aspects of social life, including education. In general, critical race theorists do not assert that race is the only thing that matters, but that race intersects with many other important factors that determine life chances, like class and gender. Like their predecessors studying law, critical race theorists examining education emerged from studying African Americans and school achievement. Acknowledging that gender and race do account for many differences observed in educational attainment, it still remained a fact that middle class African-Americans had significantly lower academic achievement than White Americans (Ladson-Billings and Tate 1995).

Discourses and Cultural Hegemony

Critical race theory is not simply about overt racism. Scholars and educators—and most people in general—like to view themselves as non-racist. Critical race theorists examine the often very subtle ways that racism plays itself out in various social structures. In fact, they point to how racism has become “normal” in society (Ladson-Billings 1998). Their mandate is not simply to highlight race as a topic of study, but also to point to how traditional methods, texts, and paradigms, combined with race and class, contribute to discourses which impact upon communities of colour (Solorzano, Ceja, and Yosso 2000). There are dominant discourses in Canadian society which, critical race theorists argue, favour White culture. A very simple example is to look at how the topic of “family” is discussed in classrooms. A curriculum that is based upon North American “White” culture may assume that “family” means two parents (a male and a female) and their children. When teachers are discussing “the family,” this may be what they are assuming everyone understands and experiences in their home life. If, however, a child comes from a different background where “family” constitutes an extended family or even an entire community, he or she would be subject to a dominant discourse that does not reflect his or her lived reality. See Box 2.8 for an additional example of how discursive practices influence curriculum.

Box 2.8 – Canada the Redeemer: Discourse and the Understanding of Canadian History

Schick and St. Denis (2005) describe how curriculum is a major discourse through which White privilege is maintained. Drawing on the term “Canada the Redeemer,” coined by Roman and Stanley in 1997, they argue that curriculum has normalized Whiteness by creating a national mythology around the history of Canada. In particular, the discourse that is perpetuated is one that characterizes Canada as being “fair.” The intentionally ironic phrase “Canada the Redeemer” refers to the discourse that surrounds Canadian culture as being perhaps a “little bit racist” but “nowhere as bad as the United States,” and that Canada “saves” people from racism and provides a safe haven. The mainstream discourse of Canadian culture tends to emphasize that Canada is a peaceful and multicultural society and that early pioneers’ hardships and toil tamed the land into what we enjoy today. Shick and St. Denis argue that this discourse favours a particular “White” perspective and reveals only a very specific view of how Canada originated—one that is highly debatable, particularly if the perspective of Indigenous People are taken into account.

Schick and St. Denis argue that Whiteness as the dominant cultural reference is embedded in everyday taken-for-granted “knowledge”—so much so that it in effect becomes invisible and permeates all aspects of curriculum. White students may believe that hard work and meritocracy allowed their ancestors to earn their place in society, but this fails to acknowledge that racist policies limiting Indigenous education actually enabled the success of White students. Canadian history curriculum has traditionally taught that Canada was particularly generous to White European settlers, “giving away” land to these newcomers. Such a historical discourse fails to recognize that this free land was originally taken by violent and coercive means from the original inhabitants. The authors, speaking about the discourse surrounding Canada’s national identity, state that “one point of pride about how Canada is different from the United States depends on the construction of an egalitarian, not racist, national self-image. There is a great deal at stake in keeping this mythology intact” (p. 308). The authors suggest that it is necessary that anti-racist pedagogies are promoted within the classroom. These ways of teaching students specifically address the taken-for-granted, day-to-day practices of how White identities are produced and maintained. Antiracist pedagogies specifically confront the notion of “White culture” being normative and “natural” and conceptualize these assumptions as being a major force in the perpetuation of subtle forms of racism.

The idea of cultural power also relates back to Italian sociologist Antonio Gramsci, who popularized the term hegemony (Gramsci, Hoare, and Smith 1971). While Gramsci himself was associated with Marxism, aspects of his writings on power relationships have been useful for critical race theorists and feminist scholars alike. refers to popular beliefs and values in a culture that reflect the ideology of powerful members of society. In turn, these values are used to legitimate existing social structures and relationships. It is a form of power used by one group over another, largely by consensus. The widely accepted definition of the family described above would fit into this category of cultural hegemony in Canada. Cultural hegemony also exists, to a much larger extent, in the dominance of “Whiteness” and White values in much of Canadian society. Pidgeon (2008) has written about how the typical Canadian definition of “success” in post-secondary education refers to finishing a program and making financial gains as a result. Success, however, for Indigenous students means something much more complex. According to Pidgeon, “success in university for many Indigenous nations means more than matriculating through prescribed curriculum to graduation. The benefits of university-trained Indigenous peoples extend beyond financial outcomes. Higher education is valued for capacity building within Indigenous nations toward their goals of self-government and self-determination. Higher education is also connected to empowerment of self and community, decolonization and self-determination” (2008:340). The author argues that counter-hegemonic discourses around the notion of success must be entertained by university officials to improve Indigenous student retention.

Racialization

is the process by which various groups are differentially organized in the social order (Dei 2009). These groups exist within hierarchies of power that value the identity and characteristics of one group over all others. According to CRT, “Whiteness” and the culture surrounding Whites is prioritized in our culture, and various social institutions, including those responsible for education, embrace those values (whether they acknowledge it or not) which place racialized individuals at an inherent disadvantage. White privilege is embedded in a discursive practice that legitimizes hierarchies that are based on race (Schick and St. Denis 2005). An important task for teachers, students, administrators, and researchers is to question how the privilege associated with Whiteness keeps existing power positions in place. See Box 2.9 for additional discussion of Whiteness.

If White culture is understood as the “norm,” and the practices and beliefs from this culture are embedded in the curriculum of our places of education, students from non-White backgrounds will be at a disadvantage in variety of ways. First, their own cultural knowledge and practices are, by default, considered illegitimate at worst, or “weird” or “exotic” at best. Second, they are made to adapt to White culture in order to succeed. In the words of Ladson-Billings (1998:18), they are made to follow a curriculum based upon a “White supremacist master script.” Third, teaching strategies developed from the Euro-Canadian culture may fail with racialized students, thus labelling such students as “high risk.”

Box 2.9 – What Is Meant by “Whiteness”?

Critical race theorists speak a lot about “Whiteness.” But what is Whiteness? Is it appearance? is it a race? or a culture? How should we understand Whiteness? Within CRT, Whiteness refers to people who are phenotypically (i.e., appear as) Caucasian and have experienced the socialization of living in a culture where they are the dominant group. Whiteness implies the general shared value and cultural experiences of Caucasians in Canada as the dominant group. Their values and ways of thinking are the default for “normal” in Canadian society and for all societies where colonialism has resulted in racial inequality. In a qualitative study of White student teachers, Solomon, Portelli, Daniel, and Campbell (2005) illustrate how they resisted and downplayed their own racial identities. They tended to argue that their successes in life were due to merit and hard work alone and that White privilege did not exist in Canadian society. Many voiced hostility at the suggestion that their achievements were the outcome of anything but their own diligence. It is not surprising that many student teachers reacted to the suggestion that they possessed “White privilege” (and that this permeated into areas of their lives and clouded their judgment) with some degree of hostility. Indeed, anti-racist educators have identified this as an uncomfortable yet necessary stage of anti-racist pedagogy (McIntyre 1997; Schick and St. Denis 2005; Solomon et al. 2005).

Millington, Vertinsky, Boyle, and Wilson (2008) used a critical race approach in their examination of Chinese-Canadian masculinities and physical education (PE) curriculum in Vancouver, British Columbia. The authors examined how, historically, Chinese boys are stereotyped as “unmanly” by White boys, as they are characterized as studious and passive. The authors note how this specific definition of masculinity prevailed in a Vancouver high school. This White, middle-class definition of masculinity was realized through the rewarding of physically aggressive performances in PE class by these males and by their physical and verbal intimidation of the Chinese-Canadian males. The researchers noted how the types of games played in the PE curriculum—like football and dodgeball—rewarded this kind of behaviour, while marginalizing the Chinese-Canadian boys. Furthermore, the teachers did not see these unfolding dynamics as acts of racism, although they had a key role in facilitating such hegemonic masculinities.

In contrast, Levine-Rasky (2008) uses CRT in an analysis of a neighbourhood school referred to as Pinecrest, within a large Canadian city. From the 1960s to the late 1980s, the school that served a particular area was comprised of a relatively homogenous student body which reflected the makeup of the neighbourhood—Jewish from a high socioeconomic background. Starting in the 1990s, a neighbouring community that was made up largely of new immigrants was beginning to grow. As a result, children from the neighbouring community started attending Pinecrest, eventually resulting in a stark shift in the demographic of the school. Levine-Rasky spoke to parents in the neighbourhood, many of whom themselves attended Pinecrest as children, to see if they sent their own children there. Nearly half of their own children who were entitled to attend Pinecrest (due to the catchment area) did not. The author explored the reasons these parents had for sending their children elsewhere and found that many of these parents were engaged in maintaining their “Whiteness” and “middle-classness.” Rather than being overtly racist or ethnocentric, the parents often indicated their reservations stemmed from their belief that immigrant children may somehow disrupt he educational process by requiring disproportionate attention or having parents who did not understand the value of education.

An important extension of critical race theory is anti-racist pedagogy, which refers to classroom techniques and curricular approaches that address racialization. This will be covered in Chapter 5.

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was a German intellectual and revolutionary known for his creation and endorsement of socialism and communism. Marx was a prolific writer, and among his many books were The Communist Manifesto and three volumes of Das Kapital. Writing during the industrial revolution in Europe (a point in history which markedly changed how goods were produced and thereby how people earned a living), Marx believed that all social relations were rooted in economic relations, particularly the mode of production, which refers to the way of producing goods and services. In capitalist systems, the mode of production is such that it places workers and owners in direct opposition to one another. Both groups have differing interests: the workers, for example, want to command the highest wage, while the owners, in order to drive the greatest profit, want to pay the lowest possible wage. This relation of production under capitalism, or the social relations that stem from capitalism, means that workers are always subservient and dependent on owners.

Marx viewed society as divided into distinct classes. At the most basic level, there were owners (the bourgeoisie) and workers (the proletariat). He argued that the only way to achieve a just society was for the proletariat to achieve class consciousness—to collectively become self-aware of their class group and the possibilities for them to act in their own rational self-interest.

The idea of is at the very core of Marx and Marxist scholarship. While Marx was a prolific writer, he wrote relatively little on education. However, he did emphasize that class relations spilled into all aspects of social life, therefore the role of education in society—capitalist society—would be a topic of much relevance under a Marxist framework. In particular, the educational system of a society exists to maintain and reproduce the economic systems of society. Institutions in society, including education, were the outcome of activities and ideas that were created through the specific material conditions and circumstances surrounding them.

Box 2.2 – Critical Pedagogy and Its Marxist Roots

Critical pedagogy is a term that frequently comes up in neo-Marxist approaches to teaching. refers to a general philosophy of teaching that recognizes and attempts to rid the classroom and teacher–student interactions of relationships and practices that perpetuate inequalities. Paulo Freire, a Brazilian educator, is credited with starting this movement with the publication of his highly influential book Pedagogy of the Oppressed in 1970. Freire uses a metaphor of “banking” to describe how the education system is organized—students are empty banks and teachers deposit knowledge into them. Freire rejects this model, arguing that this assumes that the object of education (the student) knows nothing and has nothing to offer to the “educator,” which serves to dehumanize both the student and the teacher.

Many prominent education researchers have been influenced by the work of Freire, including Henry Giroux and Peter McLaren. Giroux is currently a professor of English and Cultural Studies at McMaster University and has published about 35 books and 300 scholarly articles. His most recent interests have focused on how the media represent youth and negatively influence current pedagogical practices (Giroux 2010; Giroux and Pollock 2010).

Canadian-born McLaren is a professor of Education at UCLA and has written over 45 books, along with hundreds of scholarly articles (see, for example, McLaren 2010; McLaren and Jaramillo 2010). McLaren is known for his work in promoting a radical critical pedagogy which “attempts to create the conditions of pedagogical possibility that enables students to see how, through the exercise of power, the dominant structures of class rule protect their practices from being publicly scrutinized as they appropriate resources to serve the interests of the few at the expense of the many” (McLaren 2010:5). Like the neo-Marxists described above, McLaren understands schools as being a place of social reproduction, and his critical pedagogy is aimed at dismantling this process which results in what he views as the continued oppression of many.

Critical pedagogical approaches are used extensively in Canadian research. For example, Barrett et al. (2009) interviewed 47 teacher-educators from Ontario’s New Teacher Induction Program from eight different faculties of education across Ontario. The researchers used elements of McLaren’s approach to critical pedagogy, indicating that teacher-educators suggested that the curriculum of teacher training contained elements that reduced the likelihood of teachers adopting a critical pedagogical perspective. One example is the pairing of new teachers with senior colleagues who were not likely receptive to the idea of introducing emancipatory teaching practices.

Credentialism

Status groups often limit membership based on credentials. Credentialism is a major theme in Weberian (and neo-Weberian) discussions of the sociology of education. refers to the requirement of obtaining specific qualifications for membership to particular groups. More specifically, the actual skills obtained through these credentials are often not explicitly associated with the job’s task. Many entry-level office jobs or jobs in the civil service require new recruits to have a university degree, although the skills required in these jobs may have nothing to do with the degree that individuals have. This is an instance of credentialism. People with many years of practical experience in a given field but who have no degree may be denied jobs or promotions because they have no formal credentials.

Randall Collins is probably the best-known sociologist of education working in a neo-Weberian framework. Like neo-Marxism, neo-Weberian approaches refer to modifications to Weber’s theories that have occurred in the twentieth century forward, but still retain many of the core elements of Weber’s writings. In 1979 he published The Credential Society, a book that continues to be influential in the study of credentialism. He coined the term to refer to the decreased value of the expected advantage associated with educational qualifications over time. You may be familiar with the popular notion that a bachelor’s degree is now equivalent to what a high school diploma “used to” be. This is an example of credential inflation—that expected returns to a university degree now are what the high school diploma used to be “worth” a generation ago. See Box 2.3 for examples of studies in the sociology of education drawing on Weberian and neo-Weberian perspectives.

Box 2.3 – Weberian Approaches to the Study of the Sociology of Education

Weber’s (1951) major study of how occupational status groups controlled entry with credentials was done in China, where he described how administrative positions were granted to individuals based upon their knowledge of esoteric Confucian texts, rather than on any skills that were particular to that job (Brown 2001). Weber described how the “testing rituals that gained one admittance to sectarian religious communities and the various forms of economic and political credit they afforded were predecessors to the formalized educational credential requirements for employment in the modern era. Formal educational claims of competence were inseparable from jurisdictional issues (politics) of employment, that is, from position monopolies that were based on substantively unassailable cultural qualifications” (Brown 2001:21). In other words, credentialism, in its many forms and through many processes, has been around in various cultures for some time and serves to reproduce culture and protect status groups.

Taylor (2010) recently examined credential inflation in high school apprenticeships in Canada. She notes that education policy-makers have shown an interest in making the “academic” and “vocational” streams in high school education more comparable by mixing these curricula. The typical trajectory is for teens to attend secondary schools where they can take courses in various subjects (vocational and academic) and receive a diploma upon credit completion. However, Taylor’s data analysis showed that vocational education occupied a vague position within secondary education, particularly when credentialism was being emphasized. Trades training continues to be stigmatized and associated with less intelligent students, despite efforts to integrate the programs. Instead of an integration of these programs, the researcher instead saw a pronounced effect of educational stratification and an “intensification of positional competition” where students tried to further differentiate themselves in the labour market.

Foster (2008) traces the professionalization of medicine in Canada in his analysis of foreign-trained doctors. The medical profession is a status group that requires certain credentials for entry. In Canada, that credential is a medical degree from Canada (or a recognized foreign institution). Foster asks why there is a doctor shortage while there are so many foreign-trained doctors in Canada who are unable to practise. He argues that the professional closure of the medical profession in Canada is regulated so that foreign-born, non-European and non-White practitioners are at a serious disadvantage.

Box 2.4 – Recent Examples of Symbolic Interaction Theory Used in Education Research

How do ethnic minority students perceive racism in their teachers? This is the question Stevens (2008) asked in his study of Turkish students in a vocational school in Belgium. Stevens was interested in exploring how ethnic minorities in a White, Flemish educational institution defined racism and how particular contexts and interactions between students influenced the students’ perceptions of racism. He found that students made different claims about racism based on perception, which were very specific to students and particular contexts. The students regarded “racist-joking” by teachers to be perceived as racist only if there was a definite racist intent. He also found that students did not evaluate teachers’ ability to teach based on their perceived racism of that teacher; perceived racists were also considered good teachers by some students.

Alternatively, Rafalovich (2005) used an SI approach to examine how children’s behaviour was “medicalized.” Interviewing teachers, parents, and clinicians from two cities in North America (one in Canada, the other in the United States), Rafalovich examined language to reveal how certain childhood behaviours were contextualized by educators as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Typically, the behaviour was escalated to a potential “medical” problem (rather than just an individual behavioural characteristic of being a child, such as “daydreaming”) when teachers started to compare such children with other children in the class. While not denying the existence of ADHD as a medical problem, the author argues that this process often acted to assign meanings to behaviours as a problematic medical condition, instead of typical childhood behaviours. Rafalovich argues from an SI perspective that the meaning of the behaviour of acts such as “daydreaming” are open to interpretation. The author examines how teachers, who are not certified to make official diagnoses, play an important role in the medicalization of children’s behaviours.

Cultural Reproduction Theory

Cultural reproduction theory is most closely associated with the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1930–2002). Bourdieu is one of many theorists associated with what is known as poststructuralism. Poststructuralism is a reaction to structural functionalism, which favours the importance of social structures in explanation of social life over individual action. is associated mostly with the writings of a fairly diverse set of French philosophers (including Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault) whose only substantial area of agreement was that structuralism was flawed. There is no tidy definition that encompasses all the major theorists associated with poststructuralism—their areas of writing were all very disparate.

Like many social theorists, Bourdieu wrote on a host of topics. Bourdieu was markedly influenced by Marxism, as he believed that social position (class) greatly determined the life chances of people. But he disagreed with the Marxist notion of class and argued that social stratification processes emerged from a variety of difference sources, such as the forms of capital. Bordieu’s writings that pertain specifically to education (1977, 1984, 1986) will be focused on here and deal with the role of cultural reproduction in the education system. Like many theories, it is necessary to understand various terms the theorists in question used.

The Forms of Capital

Many social theorists talk about “capital.” The term capital is borrowed from the discipline of economics and is used to describe tangible assets. The idea of capital is typically associated with money and assets that are easily converted to money. Social theorists have borrowed the term capital and used it to refer to other assets that people possess, such as their social skills and cultural knowledge.

Bourdieu is perhaps most well-known in the field of education for his contributions in the area of cultural capital. It is not easy to define cultural capital, as Bourdieu himself defined the term in several different ways throughout the course of his writings. But the characteristic that his various definitions shared is that refers to high status cultural knowledge possessed by individuals. High status cultural knowledge is acquired by experience and familiarity with high culture activities, such as going to the opera, ballet, or theatre as well as the appreciation of art, literature, and classical musical, and theatre attendance. It is theorized that familiarity with these forms of leisure allows individuals to give off signals that give them advantage in high status circles. Bourdieu argued that children with cultural capital were appraised more favourably by their teachers than children who did not possess this form of capital, even though this form of capital did not necessarily impact on how well the child was doing in school. Familiarity with high culture may give a child more sophisticated language skills, for example, which may result in the teacher rating that child more positively.

Cultural capital is one vehicle through which culture is reproduced. By , it is meant that the high status classes reward individuals who exhibit the traits and possess the knowledge of the upper class, therefore maintaining their power. Having cultural capital gives individuals access to exclusive social circles that those who do not possess cultural capital cannot penetrate. The honing of (or investment in) this capital occurs over the life course. In the case of upper class families, children are groomed to have certain cultural knowledge and mannerisms from a very young age. Children exposed to high culture will adopt the language and knowledge associated with participation in these leisure pursuits, and as a result of this, may give cues to teachers that will result in their preferential treatment in the classroom (Bourdieu 1977). These signals are very similar to what Bernstein (1971) referred to as “language codes.” This is essentially Bourdieu’s argument about how inequality persists in schools, despite efforts to base academic achievement solely on merit and ability.

As well, cultural capital functions by a principle of cumulative advantage (for those who possess it) or cumulative disadvantage (for those who do not have any). While there are types of tastes and styles associated with all social classes or subgroups, only those that are able to potentially further economic and/or social resources are considered cultural capital.

In addition to cultural capital, Bourdieu (1986) identified (at least) two other broad types of capital. The first is , which refers to characteristics that are quickly and relatively easily converted into money. Educational attainment, job skills, and job experience are included in this type of capital as their transformation into money is a well-understood process. The second type of capital is , which Bourdieu conceptualized as micro-based in networks and individual relationships that potentially led to access to resources.

These forms of capital do not exist in isolation from one another, but are closely linked. Each form of capital is convertible into another form. Economic capital is at the root of all capitals such that economic reward can be derived from both social and cultural capital. For example, signals of cultural knowledge (such as the ability to speak in an “educated manner”) are rewarded in the classroom, which is easily converted into a type of economic capital—educational attainment.

As Bourdieu was a poststructuralist, his theoretical positionings were somewhat in response to structuralism. Bourdieu was not content to advocate a theory according to which individuals were either bound by social structures or where individual agency was prioritized. His solution to the structure/agency problem was the habitus. The habitus can be understood as embodied social structure—that piece of social structure that we all carry around in our heads, and which largely regulates our actions. The habitus guides our behaviours, our dispositions, and our tastes. It originates from our lived experience of class and the social structures in which we have become familiarized and socialized. Our decisions may be our own decisions, but they are greatly guided and restricted by the social structure that exists within each of us (see Figure 2.3).

Field is another major concept used by Bourdieu. Field refers to social settings in which individuals and their stocks of capital are located. Fields are important because it is only within these contexts that we can understand how the rules of the field interact with individuals’ “capitals” and their habitus to produce specific outcomes.

Box 2.5 – Applying Bourdieu’s Theory to the Study of Education

Lehmann (2009) used Bourdieu’s ideas of cultural capital and habitus to explore how first-generation university students from working class backgrounds integrated into the culture of the university. Being “first generation,” these individuals were the first persons from their families to enter university. Bourdieu himself argued that universities (especially elite ones) are places where the possession of cultural capital is particularly important for success. Students from working class backgrounds, however, are at a disadvantage because they typically do not possess much cultural capital. Lehmann was interested to see how these individuals coped with being university students—the university being a field that was mismatched to their class, and stocks of capital. Lehmann conducted qualitative interviews with 55 first-generation students at a large university in Ontario at two points: (1) at the beginning of their studies in their first year, and (2) at the beginning of their second year. Lehmann found that students compensated for their deficiencies in cultural capital by focusing on aspects of their social class background that they felt gave them an advantage. The habitus of the working class students was characterized by a strong work ethic, maturity, and independence.

Taylor and Mackay (2008) studied the creation of alternative programs within the Edmonton Public School Board. The EPSB is well-known for its policies on school choice and alternatives, and combined with provincial policies from the 1970s, much flexibility has existed for the creation of alternative programs. The authors focus on the creation of three alternative programs between 1973 and 1996: a Cree program, a fine arts program, and a Christian program. The authors note that alternative programs are tied to fields that are stratified by race and class. They noted that some proponents of the different schools found it easier to access social and cultural capital to exert influence than others. Advocates for the Cree school had to find individuals with cultural capital (university professors) to back them in order to be considered legitimate, while advocates for the Christian school had individuals with vast stocks of economic, social, and cultural capital in the core of their membership.

The school setting is an example of a field (Bourdieu and Wacquant 2002). Students bring their social, cultural, and economic capital and their habitus to this field, and the power relations within this field (teachers, principals) interact with them to bring about certain outcomes. Getting good grades is valued in the educational field, but a student’s cultural capital may impact on his or her grades because teachers have been found to reward students who possess cultural capital more favourably than students who do not (Bourdieu and Wacquant 2002). See Box 2.5 for how Canadian researchers have used Bourdieu’s framework in education research.

Social Capital Approaches

While Bourdieu discusses multiple forms of capital, other theorists have focused solely on the important role that social capital plays in the educational outcomes of young

Another theorist associated with social capital is Robert Putnam (b. 1941). To Putnam, “social capital refers to connections among individuals—social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them” (2000:19). In this view, social capital is more a characteristic of societies than individuals (Portes 1998). Putnam emphasized membership to voluntary organizations as key indicators of social capital in communities, with the steady decline since the 1960s as proof that social capital is on the decline in the United States.

Putnam identified two different types of social capital: bonding capital and bridging capital. is considered “exclusive” in the sense that it occurs within established groups in order to reinforce group solidarity, whereas is “inclusive” in that it is used for information diffusion and linkage to other groups. Bonding capital is useful for reinforcing group solidarity and identity, while bridging capital is useful for diffusion of information and network expansion (Putnam 2000:22–23).

While Putnam regarded social capital as a characteristic that is contingent upon the social and economic specificities of individual societies, Field (2003) notes that Putnam has been criticized for failing to clearly account for the processes underlying the creation and maintenance of social capital in communities. Like Coleman, Putnam’s understanding of social capital is rather celebratory of “the good old days,” with little consideration of the potentially negative aspects of social capital. Both Coleman and Putnam regard social capital as a remedy for various social problems in American cities. See Box 2.6 for an example of how social capital theory has been used to study university education in Canada.

Box 2.6 – Immigrants and the Role of Social Capital in University Education

Abada and Tenkorang (2009) were interested in social capital’s impact on the pursuit of university education among immigrants in Canada. Particularly, they wanted to examine how different ethnic groups used different forms of social capital to their advantage. Social capital theorists tend to discuss social capital in very broad terms, and therefore there are a lot of different ways of understanding what social capital actually is. Coleman emphasized the role of the family in providing social support while Putnam focused on civic engagement (ties to the community). Abada and Tenkorang looked at the role of family characteristics (including how much of a sense of “family belonging” individuals had), the extent to which individuals participated in community events, and how much trust they had for family members, people in their neighbourhood, and people in their workplace. Abada and Tenkorang also argued that language usage among friends could be thought of as social capital, as speaking in one’s mother tongue may be understood as maintaining ties among members of ethnic groups.

Abada and Tenkorang found that intergenerational relations in the family facilitated the pursuit of post-secondary education among immigrants, supporting Coleman’s idea for the importance of intergenerational closure (i.e., parents interacting with parents of other children) on achievement. In terms of minority language retention, however, the researchers found that this can actually inhibit academic achievement, suggesting that while it may have positive effects in connecting individuals to their communities, it may also prevent them from making connections with external social networks that lead to a larger variety of opportunities. The researchers also found that different aspects of social capital mattered more to different ethnic groups. In particular, trust was found to be much more important to the success of Black youth compared to the other ethnic groups examined. The researchers suggest that a chronic misunderstanding of this group’s culture by the education system has potentially led to a greater mistrust of school authorities, which may have made trust a key issue among Black youth.

Micro/Meso/Macro Aspects of Social Capital

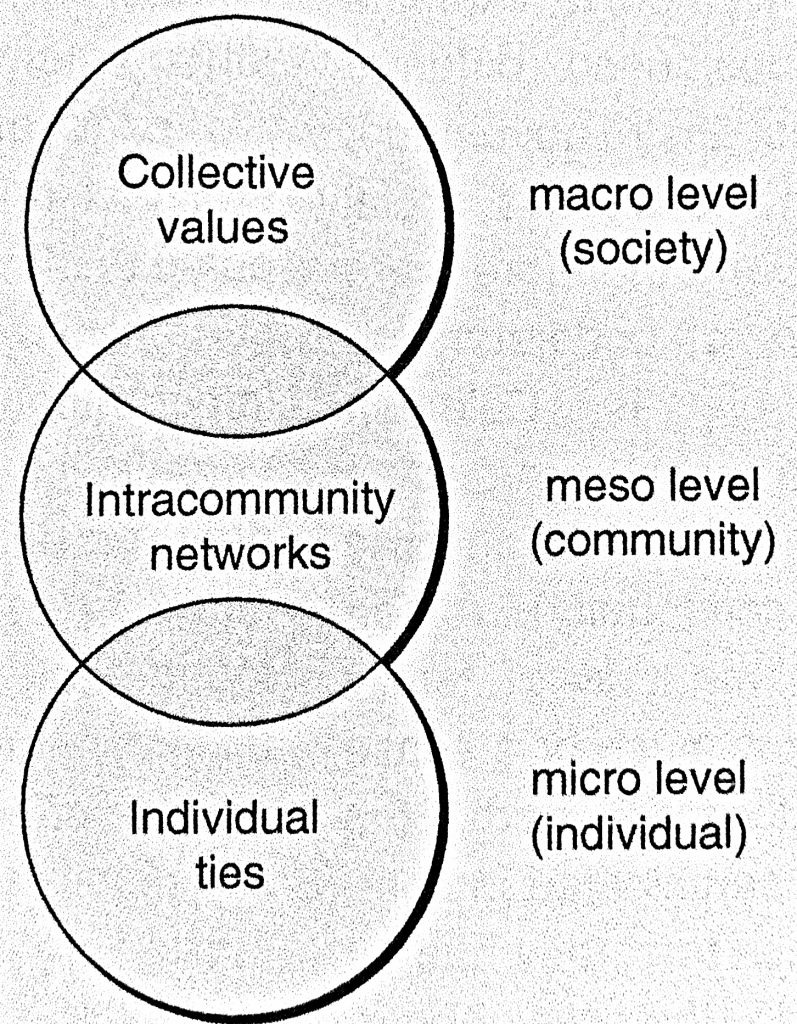

Social capital, as described above, is unique in that it is one of the few concepts associated with sociology of education that is explicitly discussed in terms of its micro, meso, and macro aspects (see Figure 2.4). Bourdieu discusses social capital as a characteristic that people have—their connections and networks. This is a micro-social approach to social capital. Putnam, on the other hand, speaks of social capital as it being a property of societies—a very macrosocial approach. He also suggests the idea of bridging capital, which connects groups to each other—which is a mesosocial idea. Coleman, in contrast, speaks of social capital that emerges out of individual actions (e.g., the micro acts of parents) that serves to create close-knit communities (a macro effect). To Coleman (1987), the ability of individual effects to serve the public group was evidence of a micro–macro linkage.

Social Mobility Approaches

Social mobility approaches within the sociology of education examine how social class positions influence the educational achievement and attainment of individuals. refers to the ability of individuals to move from one social class to another. Much previous research has shown that social class background matters for educational achievement and attainment—this is not news. But how researchers approach this process does indeed vary considerably. Below, the approaches of Raymond Boudon and John Goldthorpe are considered.

French sociologist Raymond Boudon (b. 1934) identified what he called primary and secondary effects of class differentials on educational attainment (Boudon 1973). are differences between classes and educational attainment that relate directly to academic performance. In other words, children from working-class families doing worse on standardized tests than their peers in the higher social classes would be considered a primary effect. Primary effects are dependent on characteristics of the family of origin, such as wealth, material conditions, and socialization.

, however, refer to the difference between the classes and educational attainment that relate to educational choices irrespective of educational performance. In a very simplistic example, a secondary effect would be if two individuals who were doing equally well at school were from opposite social classes and the working-class student decided to pursue an apprenticeship in the trades and the middle- or upper-class student decided to go to university. Unlike primary effects, secondary effects are entirely dependent upon choices made by individuals and their families. In a similar vein, many researchers have found that even when children from the working class perform at the same levels as middle- and upper-class children, they tend to have less ambitious educational goals (Jackson, Erikson, Goldthorpe, and Yaish 2007).

One assumption underlying the idea of secondary effects in Boudon’s theory is that children from the lower social classes have limited ambitions because they are socialized that way. Boudon (1981) argued that middle-class families had to encourage their own children to aspire to higher levels in order to simply maintain their status. Working-class children, however, may not be pushed as hard because the requirements to maintain the same social class is necessarily lower than for the middle classes. Researchers from around the world have asked how relevant primary and secondary effects are on the academic achievement of children. Nash (2005) found that in Canada, the secondary effects were found among high school students, showing that students who had high aspirations were likely to have higher grades and come from higher social origins. Nash also found, however, that these secondary effects on school achievement were relatively minor compared to overall primary effects.

Dutch researchers (Kloosterman, Ruiter, de Graaf, and Kraaykamp 2009) have also explored how primary and secondary effects impact on the transition to post-secondary education (i.e., beyond high school). They also explored whether secondary effects had diminished over time, given the emphasis placed on the importance of post-secondary credentials in Dutch culture. The authors found that in Dutch society, the importance of primary effects in determining educational inequality had grown between 1965 and 1999.

Similarly, Swedish (Erikson 2007) and British (Jackson et al. 2007) research has also found that the impact of primary effects on the transition to post-secondary education has significantly increased over time. In the Netherlands and Sweden, the lessened effect of secondary effects (and increase of primary effects) from the late 1960s to the 1990s were at a similar level, while in Britain the effect of primary characteristics was much greater. Overall, this suggests that cross-nationally, individual social backgrounds are at the root of educational inequality and that aspirations play a lesser, yet still important, role.

Bronfenbrenner and Ecological Systems Theory

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917–2005) was the founder of ecological systems theory. As an educational psychologist, Bronfenbrenner made numerous contributions to American education policy during his life. Most significantly, he was co-founder of the Head Start program in the United States. Head Start began in 1965 as a set of educational, nutritional, health, and parental involvement intervention programs aimed at low-income children in the United States.3 These programs stem from Bronfenbrenner’s theory about the nature of child development and how children are profoundly affected by various aspects of their environment. His asserts that child outcomes are the results of the many reciprocal effects between the child and his or her environment. For example, how children are treated by parents and by their peers has a strong influence on their development. Children who are mistreated by their parents and bullied by their peers will have less favourable developmental outcomes than those who are raised in a positive and nurturing environment and get along well with other children.

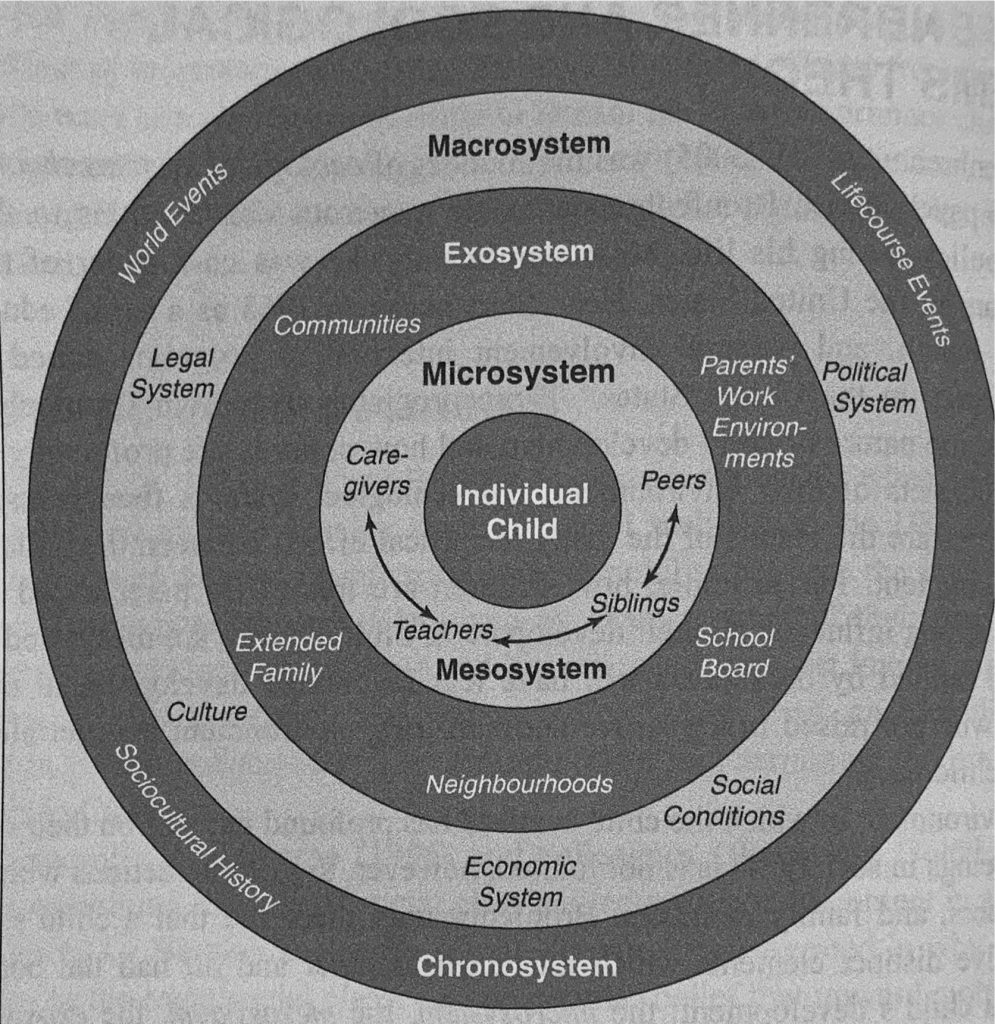

The environment in which the child is raised has profound impacts on their outcomes as human beings in society. This is not limited, however, to just interactions with parents, peers, teachers, and family members. Bronfenbrenner theorized that a child’s environment had five distinct elements which interacted together and all had the potential to impact on a child’s development: the microsystem, the mesosystem, the exosystem, the macrosystem, and the chronosystem. The micro, macro, and mesosystems relate very closely to the way microlevel, mesolevel, and macrolevel were defined earlier in this chapter. refer to the immediate setting in which the individual lives and his or her individual experiences with family members, caregivers, friends, teachers, and others. The biological makeup of the child (including temperament) is also included in the microsystem. The refers to how various microsystems connect to one another; so for example, mesosystems are concerned with how children’s interactions with their parents may carry over into how they interact with their teachers. The level contains people and places with which the child may not be directly involved yet still be impacted by. A child may not have any direct interaction with a parent’s workplace, but the outcomes of the interactions that occur there will have an impact on him or her. Parental job stress or job loss will definitely impact the child in terms of the parent’s disposition in the home (in the case of job stress) or the economic resources he or she can provide (in the case of job loss). concern the larger environment in which children live—urban or rural, developed or underdeveloped, democratic or non-democratic, multicultural or not, for example. The final system, the , relates to the socio-historical changes and major events that influence the world. For example, the chronosystem is vastly different for people during a time of war than during a time of peace. The way that particular ethnicities are regarded during specific historical times is also a chronosystem feature. For example, the way that Indigenous People have been treated historically in Canada is part of the larger chronosystem of how they experience social life. How Muslims are regarded in post–September 11 North America is also part of the chronosystem.

As you can see, elements of all these systems work together to shape the development of children, and many of them are beyond the control of the parent. This theory recognizes that while parents have an important role in shaping the lives of their children, there are bigger, external forces over which they have no control, but which similarly impact on their child’s development. Figure 2.5 illustrates how these systems all relate to each other and different characteristics that comprise each system.

Source: Adapted from Urie Bronfenbrenner, The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1979).[h5p id="5"] Chapter Summary

In this chapter, several theoretical perspectives have been described, all of which have application to the study of the sociology of education. The chapter began by introducing theoretical terminology that is embedded within many theoretical perspectives: macro-social theory, microsocial theory, mesosocial theory, middle range theory, agency/structure, and ontology and epistemology. The first theoretical perspective that was discussed was structural functionalism, which is associated with the work of Émile Durkheim, and later, Talcott Parsons. The critical perspective of Karl Marx, which emphasizes the idea of social class and conflict between classes, and those who were influenced by Marxist theory (neo-Marxists) were then discussed, as was the linkage between Marxism and critical pedagogy. The next classical theorist considered was Max Weber, as well as the neo-Weberians, who emphasized the idea of credentialism within the sociology of education.

Meyer’s institutional theory was next introduced, which juxtaposes the democratic entitlement to education with the “loose coupling” that such education actually serves in the job market. The microsocial approaches of symbolic interaction and phenomenology were then briefly addressed. Next, theories focused on the reproduction of culture were considered. Social capital was also introduced, and it was shown that social capital can be understood as macro-, meso-, and microtheoretical theoretical concept. Theorists that regard education as a major component of social mobility were then discussed, with emphasis placed on the notion of “primary” and “secondary” effects.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory understood the process of child development (and hence the role of education) as being influenced from several spheres (i.e., systems) that interacted with each other to contribute to children’s life chances. The chapter ended with newer contributions from feminist and critical race theorists, who prioritize gender and race in their understanding of educational processes and practices in Canada.

When considering a particular topic area in the sociology of education, one should think about the particular theoretical perspective(s) that would be appropriate to explore it. Some will be more fitting than others. An interest in how students experience racism in the classroom, for example, is probably best addressed through the use of critical race theory while structural functionalism probably will not be helpful here. Questions around how society reproduces itself through subtle means can be approached from the perspective of the cultural and social reproduction theories that have been presented—but institutional theory or symbolic interaction probably will not be much help. A researcher must also consider his or her own beliefs about the nature of reality. What is given priority, agency or structure? What bridges the two? In terms of ontology, is meaning all essentially subjective, or is it that scientists have the task of uncovering objective facts? These are not at all easy issues to resolve and have engaged philosophers and social theorists for centuries. But all these preconceptions influence what social theories will make their way into sociology of education research.

Review Questions

1. Define what is meant by macrosocial, microsocial, and mesosocial theories.

2. Explain why ontology, epistemology, agency, and structure are important underlying concepts within the theories of the sociology of education.

3. According to critical race theory, what is meant by racialization? What is meant by “Whiteness”?

4. Define Marxism in terms of how it relates to the sociology of education.

5. According to cultural reproduction theory and social mobility approaches, what are the underlying forces that shape educational outcomes?

6. Identify and define the “systems” within ecological systems theory and how they relate to one another.

7. What is meant by “waves” of feminism? What is meant by postmodern feminism?

Exercises

- Communicate where five theorists discussed in this chapter fit on the spectrum. Explain the rationale behind your placements.

- How are Bourdieu’s concept of habitus and Boudon’s idea of secondary effects similar and how are they different?

- How is “Whiteness,” as described by critical race theorists, also related to habitus and to cultural hegemony?

- Watch the trailer of this movie, Reel Injun, and describe how cultural artefacts such as movies have constituted mainstream views of Indigenous People, and especially how Indigenous People reconcile those views amongst themselves.

- Select three theorists and explain how they attempt to link agency and structure.

- Look on the internet for information about intervention programs that have been informed by ecological systems theory, including the programs mentioned in the chapter. What were the programs? How were they informed by ecological systems theory? Were they effective?

- Look up the phrase “the myth of meritocracy.” What does it mean? Where does it come from? How can it be applied to the theories that have been discussed in this chapter?

- What topics would you be interested in studying in the sociology of education? What theoretical position(s) would be most appealing to your interests and why? Discuss in groups.

- Using sociological abstracts through e-resources in your university or college library, find a recent journal article on education that considers more than one theoretical approach. Which theories does the author(s) use? Which aspects of the theories are considered? Were the theories supported by findings? Why or why not?

- Think about your experiences in the education system up to this point. From the perspective of a postmodern feminist or critical race theorist, can you identify any instances of cultural hegemony? Have you experienced any curriculum, for example, that you recognize as promoting a hegemonic view, whether it be gendered and/or racist?

Key Terms

Refers to the individual’s ability to act and make independent choices.

Refers to aspects of the social landscape that appear to limit or influence the choices made by individuals.

A theory that calls for a sociology from the standpoint of women and focusing on the settings, social relations, and activities of women that are their own lived realities.

The critical feminist scholarship of third wave feminism that frequently scrutinizes the meaning surrounding gender and how power relations play themselves out in subtle ways.

A theory that puts race at the centre of analysis and examines how race is embedded in various aspects of social life, including education; does not assert that race is the only thing that matters, but that race intersects with many other important factors that determine life chances, such as class and gender.

The popular beliefs and values in a culture that reflect the ideology of powerful members of society; these values are used to legitimate existing social structures and relationships.

The process by which various groups are differentially organized in the social order and exist within hierarchies of power that value the identity and characteristics of one group over all others.

How gender, race and ethnicity relate to patterns of social advantage and disadvantage.

The general philosophy of teaching that recognizes and attempts to rid the classroom and teacher–student interactions of relationships and practices that perpetuate inequalities.

The requirement of obtaining specific qualifications for membership in particular groups; the actual skills obtained through these credentials are often not explicitly associated with the job’s task.

The decreasing value of the expected advantage associated with educational qualifications over time; for example, the notion that a bachelor’s degree is now equivalent to what a high school diploma used to be.

A wide collection of theories reacting to structural functionalism that favour the importance of social structures in explanation of social life over individual action; associated with the writings of French philosophers, such as Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, whose only main agreement was that structuralism was flawed.

A term associated with the work of Pierre Bourdieu that refers to the high-status cultural knowledge possessed by individuals that is acquired by experience and familiarity with high-culture activities, such as going to the opera, ballet, or theatre as well as the appreciation of art, literature, and classical music and theatre attendance.

The process by which cultural capital is maintained in which high status classes reward individuals who exhibit the traits and possess the knowledge of the upper class, therefore maintaining their power.

Characteristics that are quickly and relatively easily converted into money, such as educational attainment, job skills, and job experience.

The networks and individual relationships that potentially lead to access to resources.

A type of social capital that is “exclusive” in the sense that it occurs within established groups in order to reinforce group solidarity.

A type of social capital that is “inclusive” in that it is used for information diffusion and linkage to other groups.

The ability of individuals to move from one social class to another.

According to Boudon, the differences between classes and educational attainment that relate directly to academic performance; dependent on characteristics of the family of origin, such as wealth, material conditions, and socialization.

According to Boudon, the differences between the classes and educational attainment that relate to educational choices irrespective of educational performance, such as choosing apprenticeship over university, regardless of achievement in secondary school.

A theory by Bronfenbrenner that asserts that child outcomes are the results of the many reciprocal effects between the child and his or her environment; for example, how children are treated by parents and by their peers has a strong influence on their development.

In ecological systems theory, the ways in which various microsystems connect to one another; for example, how children’s interactions with their parents may carry over into how they interact with their teachers.

In ecological systems theory, the people and places with which individuals may not be directly involved but by which they are still impacted; for example, the effect a parent’s workplace may have on a child.

In ecological systems theory, the larger environment in which individuals live—urban or rural, developed or underdeveloped, democratic or non-democratic, multicultural or not, for example.

In ecological systems theory, the socio-historical changes and major events that influence the world.

An administrative structure that follows a clear hierarchical structure and follows very specific rules and chains of command.

The idea that the education system is set up to serve (or correspond to) the class-based system so that classes are reproduced and so that elites maintain their positions.

A branch of philosophy that studies knowledge, including how we pursue knowledge.

The method by which schools are able to reproduce the class system; the subtle ways that students are taught to be co-operative members of the class system.

The notion that the expansion in education is related to the democratic belief in the good of expanding education rather than actual demand for the levels of training.

The belief that how we understand society is fundamentally different from the natural sciences and that it is wholly inappropriate to study society in similar manners; contrary to positivism.

A theory that focuses on society at the level of social structures and populations; also often referred to as grand theories.

A theory that occupies a position between the macro and micro, directing its attentions to the rule of social organizations and social institutions in society, such as schools and communities.

A theory focused on individuals and individual action, such as the individual experiences of students.

In ecological systems theory, immediate setting in which the individual lives and his or her individual experiences with family members, caregivers, friends, teachers, and others; also includes the biological makeup of the individual.

A theory that focuses on specific aspects of social life and sociological topics that can be tested with empirical hypotheses.

A branch of philosophy that considers the way we understand the nature of reality.

A branch of philosophy that concentrates on the study of consciousness and the objects of direct experience.

The belief that the social world should be studied in a similar manner to the scientific world; contrary to interpretivism.

The process in which society became more secular, scientific knowledge began to develop, and an increasing reliance on scientific and technological explanations began to emerge and more and more social actions were the outcome of beliefs related to scientific thought instead of customs or religious belief.

A reinterpretation of rule breaking or delinquency as acts of class-based resistance in which marginalized students do not comply with the values, discipline, and expected behaviours of middle-class school structures; resisting behaviours also serve to reproduce class position—preventing the acquisition of the skills and training required for jobs outside the realm of manual labour.

The social structures that reproduce the social order of the ruling class in Althusser’s theory of ideology; the education system, along with religion, the law, the media are the forces within this apparatus.

An identifier that serves to divide society into groups with competing interests; associated with honour and privilege, independent of class membership.

Moral communities concerned with upholding the privilege of their members in society; membership is often limited based on credentials and such groups work against class unification by cutting across classes.

A body of theories that understand the world as a large system of interrelated parts that all work together.

A theory that asserts that the world is constructed through meanings that individuals attach to social interactions.