Critical Indigenous Perspectives on the Sociology of Education

Chapter 4: The Structure of Education in Canada

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

- Describe the historical significance of the Indian Act to determine that education for on-reserve First Nations children and youth would be under federal jurisdiction.

- Define pre-elementary programs and describe how they are organized in Canada.

- Explain how elementary and secondary school programs are similar across Canadian jurisdictions.

- Identify key differences in the Quebec schooling system compared to other jurisdictions.

- Define school choice and give examples of school choice in Canada.

- Explain the structure of school governance in Canada.

- Identify the differences between charter and alternative schools.

- Summarize how private schools are funded in Canada.

- Explain how universities and colleges differ in their missions and governance structures.

- Explain recent controversies over private universities.

- Describe the process of acquiring the skills of a trade.

- Explain the difference between informal and formal adult education in Canada.

Introduction

Uniquely, Canada is the only country in the world with no federal education department (OECD 2011). Instead, the 13 jurisdictions (10 provinces and 3 territories) are responsible for the delivery, organization, and evaluation of education. This decentralization of decision making to individual jurisdictions was determined in 1867 and is explicitly declared in Canada’s Constitution Act. One reason for this decentralization was to protect the interests of the different populations who inhabited the particular parts of the country, as strong ethnic and religious differences existed by region.

The structure of education is, however, very similar across the country, although there are notable differences between jurisdictions, which are due to the unique historical, cultural, geographical, and political circumstances upon which they were developed. Each jurisdiction is guided by its own , which is a detailed legal document that outlines how education will be organized and delivered, along with student eligibility criteria, duties of employees (teachers, principals, superintendents, and support staff), accountability measures, and different types of programs available.

Of course, one of the most significant differences is seen in how First Nations’ education is funded – through the federal government and not provincially. The reasons for the this and the influence of the Indian Act in creating and perpetuating this difference will be the start of this chapter.

Indigenous Education

About two-thirds of First Nations People live off-reserve and their children attend provincially-run schools with non-First Nations children. The Constitution Act of 1867 (and later the consolidation of many Indigenous-related laws into the Indian Act of 1876) stated that the Crown (the federal government) is responsible, however, for the education for First Nations People who live on-reserve. See Box 4.5 for further discussion of the education clauses in the Indian Act. Inuit and Métis people are not governed by this law. Inuit do not live on reserves but typically in municipal areas which would have territorially funded education, while Métis children living on Métis settlements would attend provincially run on-settlement schools. Specifically, it is the federal government’s responsibility to provide and fund primary and secondary education on First Nations reserves. About one in five First Nations children are educated on-reserve, with the remaining attending schools under provincial jurisdiction (Richards 2009).

Box 4.5 – The Historical Significance of the Indian Act in Delivering Education to First Nations Children

The 1867 Constitution has played a significant role in how education has been organized in Canada. First of all, the Constitution granted provincial jurisdiction over education. Within the Indian Act enacted in 1876, responsibility for “Indians” and “Lands Reserved for Indians” was delegated to the federal government, which included all aspects of their education.

Sections 114 through 122 of the Indian Act pertain specifically to education. In no uncertain language is it clear that the intention of the education sections of the Indian Act promote the use of education as an assimilation technique (Mendelson 2008). While too lengthy to replicate here, the act in its entirety can be found on the Department of Justice Canada website (http://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/I-5/ page-35.html).

As noted by Mendelson (2008), the act explains in detail that schools are to be imposed on First Nations children, whether or not they or their parents wished for them to attend. Rather significantly, the act also allows the minister of education to establish agreements with provinces and religious orders to run such schools but it does not permit the minister to make agreements with First Nations to run their own schools (Mendelson 2008).

In addition to not providing the possibility for First Nations to run their own schools, the act also indicates that the children will receive “comparable” education to other Canadian children, but does not specify how this will be ensured.

Mendelson (2008:3) argues “The Act’s core purpose was to provide a legal basis for the internment of Indigenous children and to establish government control as a means of pursuing assimilation. The Act contains no reference to any substantive educational issues, the quality of education or the rights of parents to obtain an adequate education for their children.”

While the act remains legally in force today, the language is so outdated that enforcement of the many clauses is not possible. The obsolete language and the vague wording of the act, however, mean that there is little framework from which First Nations education reformers have to improve educational policy. Mendelson (2008, 2009) argues that this lack of structure and clarity in federal policy has resulted in a “policy vacuum” which has significantly slowed the progress of any educational improvements for on-reserve students. With no actual First Nations “school system” in place and the isolation of many First Nations on-reserve schools, some specialists have argued for the creation of a separate First Nations Education Act to radically reform the current law (Mendelson 2008, 2009; Richards 2008).

Elementary and secondary on-reserve education is managed by Indigenous Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC), which runs programs that oversee the instruction of on-reserve schools and reimburses the tuition costs for students who attend off-reserve schools (which are under provincial jurisdiction). It should be noted that AANDC has undergone a name change in 2011 and previously was known as the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development since the mid-1950s. Federal policy indicates that on-reserve educational services are to be comparable to those provided by the province in off-reserve public schools.

In 1972, the National Indian Brotherhood (now known as the ) presented the federal government with a written policy on First Nations education entitled Indian Control of Indian Education. As indicated by its title, this document outlined the importance of local control, parental involvement, and culturally relevant curriculum. The was quick to respond to the position paper, handing over administrative control of on-reserve schools to the bands in the same year. There are over 500 band-operated schools on First Nations reserves in Canada, with only a few being managed by DIAND (Simeone 2011). Approximately $1.8 billion will be spent in 2012–2013 to fund the on-reserve education of around 120 000 First Nations primary and secondary school students. Most, but not all, on-reserve schools are at the kindergarten and primary level, however. Around 40 percent of normally on-reserve students attend school off-reserve in provincially run and private schools because of the absence of secondary schools on many reserves. Children of secondary-school age must often commute long distances or move off reserve in order to attend secondary school.

An important exception to federal control over First Nations education occurred in 1975, when the Cree community of James Bay, located in Northern Quebec, established its own school board. Prior to this, children were being sent off reserve to be educated in residential schools. The establishment of the Cree School Board signalled protection of Cree culture and the education of their children in their own language and traditions.16 The school board function is recognized within Quebec’s Education Act and is funded by both the federal and Quebec governments (Mendelson 2008).

In 2008, the Canadian government committed $70 million over two years to improving and reforming First Nations K–12 education.17 As a comparable, the Toronto District School Board’s annual 2020-2021 budget is 3.4 billion, which has just experienced a $67.8 million in reductions during the 2019-2020 academic year (TDSB, 2020). As discussed throughout this textbook, there is considerable evidence that on-reserve schools are not comparable to provincial schools in many aspects, given that the educational outcomes of First Nations students lag so far behind those of other Canadians. First Nations community leaders, policy-makers, and politicians have repeatedly called for overhauls to the First Nations education system with the aim of improving outcomes for First Nations students. The specific reforms that have been suggested vary by province, but include partnerships between provincially run schools and First Nations groups, and agreements that give First Nations groups more control over the education of their children and allow them to deliver an education program that is more culturally relevant.

More recent similar agreements have been reached by other First Nations groups, provincial education authorities, and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. In 1997, the Assembly of Nova Scotia Chiefs approached the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development with the idea of making a Mi’kmaq Education Authority to service the 13 different Mi’kmaq communities in the province with culturally relevant and self-governed education. In 1999, after much debate, the Mi’kmaq Education Act was incorporated into federal law and the jurisdiction of the education in these areas was transferred to the Mi’kmaq Nation (Mendelson 2009).

More recently, the B.C. First Nations have been working together with provincial and federal authorities to make amendments to First Nations education laws in their province. In 2007, the First Nations Jurisdiction over Education in British Columbia Act was passed which created a new First Nations Education Authority in British Columbia. The resulting education authority will be run by First Nations and responsible for the K–12 program in participating First Nations, including curriculum and teacher training (Mendelson 2009).

Colonial Education Structures in Canada

In general, education in Canada can be split into four distinct sets of programs: pre-elementary, elementary, secondary, and post-secondary.

Pre-Elementary Programs

Public pre-elementary programs (pre–Grade 1) are available in all jurisdictions in Canada, although their length does vary. Pre-elementary programs, often called kindergarten, are offered to 4- to 5-year-olds (usually the criterion is turning 5 by a certain date, which varies by jurisdiction). Most pre-elementary programs are not mandatory. In other words, parents can choose to skip sending their children to pre-elementary and begin schooling their children when they are old enough to enter Grade 1. In some provinces, notably Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador, however, attendance at pre-elementary is mandatory. Nova Scotia is slightly different in that the year prior to Grade 1 is called Grade Primary and it is technically classified as part of the elementary school program rather than as pre-elementary.

The intensity of pre-elementary programs also varies by jurisdiction. In many areas kindergarten is a half-day program, while in others it is full-day. Recently, Ontario, British Columbia, and Prince Edward Island have implemented full-day kindergarten. This recent attention to expanding kindergarten programs is at least partially due to reports released by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2003 and UNICEF in 2008, which showed that among economically advanced countries, Canada ranked at the bottom in terms of early education and childcare provided to 0- to 6-year-olds (see Mahon 2009 for an overview; OECD Directorate for Education 2004; UNICEF 2008). With the exception of Quebec, most childcare in Canada is paid for by individual families, which means that the earlier publicly available pre-elementary programs are offered, the easier it is for parents to return to the labour force. Recent research has also found that early childhood education and full-day kindergarten can have positive effects on academic performance in the early grades (Cooper, Allen, Patall, and Dent 2010; Fusaro 2007), particularly for children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Many jurisdictions offer more than one year of publicly available pre-elementary education, depending on the particular circumstances of families and the availability in a particular area. In Quebec, an additional year is available to children with disabilities and some children from low-income families. Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba also have additional years available to students who meet special criteria and live in areas where such provisions are available. Ontario’s pre-elementary programming is unique in Canada in that it is universally publicly available and covers two years: junior kindergarten and senior kindergarten, which children attend from age 4. By 2014, full-day junior and senior kindergartens are anticipated to be universally available in Ontario.

Elementary and Secondary Programs

In Canada, public education is free to all Canadian citizens and permanent residents. All jurisdictions require mandatory attendance for children and youth between certain ages, although this varies by area. The age at which schooling becomes compulsory is generally around 6 or 7 (as of a certain date determined by the jurisdiction). Compulsory education ages are obviously lower for jurisdictions where pre-elementary is also mandatory, like New Brunswick. The minimum age at which youth may terminate their school attendance also varies by jurisdiction. In most jurisdictions, the age is 16. In recent years, attention has been paid to increasing the age at which youth can leave school. The rationale for such an age increase is that in order for young adults to have the necessary skills to compete in the labour market, they will require the basic skills of education that is provided up to the age of 18. Much research (discussed in later chapters) also points to the poor employment prospects for high school dropouts. New Brunswick increased its age of compulsory education from 16 to 18 in 1999, as did Ontario in 2007.1 At the time of writing, the government of Alberta was currently moving toward increasing the school-leaving age from 16 to 17.

The division between elementary and secondary school also varies by jurisdiction, but in general the length of the program is 12 years (or 13, if kindergarten is included). Depending on the jurisdiction, the particular grades encompassed by “elementary” and “high school” vary, with some jurisdictions denoting grades in the middle of “elementary” and “high school” as “middle school” or “junior high.” Elementary education is typically the first six to eight years of education while high school (secondary school) begins at Grade 9 or 10. Sometimes “middle school” or “junior high” covers Grades 6 or 7 to Grades 8 or 9. Figure 4.1 illustrates the typical pre-elementary to secondary trajectories by jurisdiction.

| Province or Territory | Pre-elementary | Elementary | Primary | Junior high | Middle | Senior high | Secondary |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Yes | Grades 1-6 | Grades 7-9 | Grades 10-12 | N/A |

| Prince Edward Island | Yes | Grades 1-6 | Grades 7-9 | Grades 10-12 | N/A |

| Nova Scotia | Yes | Grades 1-6 | Grades 7-9 | Grades 10-12 | N/A |

| New Brunswick – English | Yes | Grades 1-5 | Grades 6-9 | Grades 9-12 | N/A |

| New Brunswick – French | Yes | Grades 1-8 | N/A | N/A | Grades 9-12 |

| Quebec – General | Yes | Grades 1-6 | N/A | N/A | Grades 7-11 |

| Quebec – Vocational | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Grades 10-13 |

| Ontario | Yes | Grades 1-8 | N/A | N/A | Grades 9-12 |

| Manitoba | Yes | Grades 1-4 | Grades 5-8 | Grades 9-12 | N/A |

| Saskatchewan | Yes | Grades 1-5 | Grades 6-9 | Grades 10-12 | N/A |

| Alberta | Yes | Grades 1-6 | Grades 7-9 | Grades 10-12 | N/A |

| British Columbia | Yes | Grades 1-7 | N/A | N/A | Grades 8-12 |

| Yukon | Yes | Grades 1-7 | N/A | N/A | Grades 8-12 |

| Northwest Territories | Yes | Grades 1-6 | Grades 7-9 | Grades 10-12 | N/A |

| Nunavut | Yes | Grades 1-6 | Grades 7-9 | Grades 10-12 | N/A |

The Quebec System

Quebec has a different structural arrangement of its elementary and secondary programs than the rest of the country. The first difference is that pre-elementary to the end of secondary school spans 12 years instead of 13. And instead of grades, the Quebec system has cycles. The first six years of education correspond to elementary education and are divided into three cycles. Cycle I (premier cycle) corresponds to Grades 1 and 2, Cycle II (deuxième cycle) to Grades 3 and 4, and Cycle III (troisième cycle) to Grades 5 and 6. Quebec’s secondary schools (école secondaire) are called Secondary I–V and correspond to Grades 7 to 11, spanning five years. There are two cycles in secondary school. Secondary Cycle 1 (enseignement secondaire premier cycle) corresponds to junior high school Grades 7 and 8, and Secondary Cycle 2 (enseignement secondaire deuxième cycle) corresponds to senior Grades 9 to 11.

The cycle system is different from the grade system used in the rest of Canada in that desired learning outcomes are focused on the completion of a cycle rather than a grade. In others words, children have two years to master the curriculum outcomes of each cycle, rather than a single year to master a grade-specific curriculum. Proponents of the cycle approach argue that two-year cycles allow children to learn at their own pace and foster competencies in a variety of skills.2 The curriculum gives considerable focus on “cross curricular competencies,” which refers to the development of skills that are not specific to any particular subject, such as problem-solving and planning projects (Henchey 1999).

Funding of Primary and Secondary Education in Canada

In Canada, public education from kindergarten to the end of secondary education is provided free of charge to Canadian citizens and residents if they complete their secondary education by a certain age maximum (often 19). Expenditure on public education comes from municipal, provincial, federal, and private sources. Schools receive a , which is a fixed amount of money for each student enrolled in the school (or in secondary school may be associated with number of credit hours in which the student is enrolled). In some jurisdictions, private schools also receive funding. Private schools, or independent schools, are different from public schools in that they do not receive (complete) funding from any government sources and can select their own students and charge tuition. In general, private schools that receive no government funding are not required to follow the provincial or territorial curriculum. Six jurisdictions provide partial funding for private schools (a percentage of the provincial per pupil amount) if they meet certain criteria, such as following the provincial/territorial curriculum and employing provincially certified teachers.

Public and separate school systems that are publicly funded serve about 93 percent of all students in Canada. Jurisdictions west of (and including) Quebec provide partial funding for private schools if certain criteria, which vary among jurisdictions, are met. No funding for private schools is provided in the other jurisdictions, although they still may be regulated.

School Choice

In recent years, the discussion around school choice has become a hot topic in Canada and beyond. refers to the freedom that parents (and students) have in selecting the type of school that their children attend free from government constraint, whether it is public, alternative, charter, religious, or private. Table 4.1 provides an overview of school choices available by jurisdiction.

Table 4.1 School choices by jurisdiction

| Independent | Private | Catholic School | Public Francophone | Distance Education | Other | |

| British Columbia | Divided into “Groups” based on programs and teacher certification Group 1-50%; Group 2-35%; Groups 3 and 4, no funding | Catholic schools run as independent | Yes | Yes, but must be enrolled at a public or independent school | Mandarin bilingual school |

| Alberta | Registered private schools – not required to follow provincial curriculum or have AB certified teachers not publicly funded. Accredited private schools which meet curriculum and evaluation criteria and have certified teachers funded at 60% | Separate Catholic School Board, publicly funded | Yes | Yes | Outreach program for individuals who find traditional school setting does not meet their needs. Unique charter schools alternative programs which emphasize certain language, culture, or subject areas (e.g., fine arts, German, hockey) |

| Saskatchewan | Those deemed ‘historic’ receive full funding; others do not | Yes | Yes | Some publicly funded Protestant schools | |

| Manitoba | Funded independent schools follow provincial curriculum and teachers are Manitoba certified, funded at 60% | Yes | Senior Years Technology Education Program | ||

| Ontario | Independent schools, non-funded | Yes | Yes | Yes | Alternative schools with unique approach to program delivery; Separate Protestant board consisting of one school |

| Quebec | Accredited private schools, 40% funded | Yes and public Anglophone | Yes | Public Anglophone and Francophone school boards | |

| New Brunswick | No funding for independent schools | Yes | |||

| Nova Scotia | No funding for independent schools unless private special education for children with learning disabilities | ||||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | No funding for independent schools | Yes | Yes | One Innu Native schools | |

| Prince Edward Island | Yes | ||||

| Yukon | Yes | Yes | |||

| NWT | Funded at 40% | Yes | Yes | ||

| Nunavut | Yes | Yes | Bilingual Indigenous schools |

School Governance

The term refers to the way that a school system is governed, or run. At the provincial and territorial levels, each province/territory has at least one department or ministry that is responsible for education, which is headed by a publicly elected minister who is appointed to this position by the party leader of the province/territory. At the provincial/territorial government level, these ministries and departments define the policy and legislative frameworks to guide practice and also function to provide administrative and financial management.8

At a local level, the governance of education lies in the hands of smaller units. These units vary in what they are called and how individuals acquire positions in such organizations. These local units of governance are called , school divisions, school districts, or district education councils. Their powers and tasks vary according to provincial and territorial jurisdiction, but usually include the administration of a group of schools (including the financial aspects), setting of school policies, hiring of teachers, curriculum implementation, and decisions surrounding new major expenditures. All provinces and territories have public school boards (see Table 4.2), which represent the local governance of public education for K–12 education in a particular geographic region. Historically, school boards have been regarded as democratically elected organizations which give the public a say in elementary and secondary education (Howell 2005). In addition to public school boards, separate school boards also exist in some provinces, which are discussed later in this chapter.

In all provinces and territories, the local governance of education is staffed with locally elected officials, who run during municipal elections. Often these officials are called. Depending on the province or territory, school trustee positions are often voluntary or associated with a small stipend rather than being a full-time paid position. School boards meet regularly throughout the school year and the public are often invited to attend meetings. School trustees will have different jobs depending on the particular jurisdiction in which they are working. Table 4.2 lists the departments responsible for K–12 education in each province and territory, along with the number of school boards (or similar structure) that exist in each jurisdiction. In some jurisdictions, school boards have the authority to levy a local tax on property to supplement local education. In such jurisdictions, such school boards have more control over the budgets of their district.

| Provincial Dept Responsible | School Boards | |

| British Columbia | Ministry of Education | 60 public school boards | districts |

| Alberta | Alberta Education | 62 public, separate (Catholic) and Francophone school boards |

| Saskatchewan | Saskatchewan Education | 29 school divisions – public, Catholic, Protestant, Francophone |

| Manitoba | Manitoba Education and Literacy | 39 school divisions and districts |

| Ontario | Ministry of Education | 72 school boards, 31 English public boards, 296 English Catholic boards, 4 French public boards, and 8 French Catholic boards; small number of schools managed by “school authorities” i.e., in remote areas or in hospitals |

| Quebec | Ministry of Education, Recreation and Sports | English (9) and French (60) school boards – 3 special status school boards: Cree, Kativik, Littoral (Lower North Shore) |

| New Brunswick | Department of Education and Early Childhood Development | 14 school districts, 5 Francophone, 9 Anglophone |

| Nova Scotia | Department of Education and Culture | 8 school boards with publicly elected board members |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Department of Education | 5 district school boards (1 Francophone) |

| Prince Edward Island | Department of Education and Early Childhood Development | 3 school boards (1 French language) |

| Yukon | Yukon Education | 1 school board |

| NWT | Department of Education and Employment | 8 divisional education council | school board |

| Nunavut | Department of Education | 26 district education authorities and one |

In addition to school boards and trustees, school boards are usually responsible for hiring a board , who serves as the chief executive officer for that school board. The superintendent is not a member of the school board but oversees the general supervision of the school system and implements policies that the board recommends.

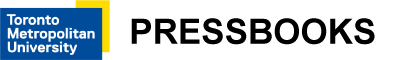

are also an important part of the structure of education in Canada. They usually are made up of parent volunteers, teachers, non-teaching staff, community members, and sometimes students who provide recommendations to the school principal and, in some cases, the school board. Many school councils are also active in organizing social events and fundraising. School councils have become required in many jurisdictions, which is one way the government has created parental involvement in education (Brien and Stelmach 2009), although critics may see it as a way of regulating parental involvement in education. Figure 4.2 illustrates these different levels of structure that are common to most jurisdictions, although the roles performed by individuals at each level can vary greatly by province/territory. See Box 4.1 for a discussion of the power struggles that can occur between the different levels of governance in the primary and secondary schooling system.

Figure 4.2 Individuals and Groups Involved in Primary- and Secondary-School Decision Making

Box 4.1 – Power Struggles in the Administration of Education

With so many levels to the structure of education in each jurisdiction, and with each level (ministers, school boards, superintendents, teachers, principals, school councils) having its own particular interests, it is not surprising that there are disagreements among the different stakeholders that result in calls for restructuring. In 1996, the Liberal government in New Brunswick abolished school boards altogether, by replacing them (led by elected officials) with school districts, which were divisions of the Department of Education. All 18 school boards were abolished and 250 newly elected trustees were removed from office. The Liberals’ rationale for the restructuring was to make the structure more efficient, streamline decision making, and create more consistency in the development and implementation of policy. New Brunswick became the only school system in Canada without publicly elected school officials.9 The government replaced the boards with local parent-run groups. Attempts by the parent-run groups to have influence in the education system were often ineffective due to the centralized nature of the new education structure. The dissatisfaction of parents was evident in protests, such as a blockade set up by parents in an effort to prevent local schools from being shut, which ended with RCMP using tear gas on the protesters.10 School boards, in the form of district education councils, were later reintroduced by the Conservative government in 2000.

The mid-1990s also saw efforts by Conservative governments in Alberta and Ontario to reduce the powers of school boards. In Ontario, under the Mike Harris government, the Fewer School Boards Act was passed in 1997, which reduced the number of school boards from 124 to 72, and the number of trustees from 1900 to 700. Salaries of trustees were also cut from $40 000 a year to $5000 a year. The platform on which the Harris government was elected in 1994 was largely based on cost-cutting of what were perceived as inefficient bureaucratic expenses. These changes also coincided with the amalgamation of several communities around Toronto into the Greater Toronto Area. The outcome of these two levels of restructuring were fewer, but much larger school boards, with fewer trustees (with minimal pay) representing much larger populations. In addition to these changes, school boards were no longer permitted to collect property tax to raise money from provincial shortfall. Instead, the Ministry of Education collects taxes and distributes them to school boards on a fixed per-student amount. School boards were also not allowed to run a deficit and were required to submit annual balanced budgets. In 1995, the Conservative government in Alberta also changed policy that disallowed public school boards from directly collecting property taxes, also switching to a standardized per-student amount.

In both Ontario and Alberta, such changes to the powers of school boards were met with much protest. Alberta school boards took the loss of their taxation revenue all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada in 2000. The Court decided that it was it was within the province’s right to reform education in the way it saw fit. In 2002, three Ontario school boards defied the provincial law which required them to submit balanced budgets. School boards in Toronto, Hamilton, and Ottawa submitted deficit budgets. They argued that the funding they received from the province did not adequately cover the expenses they met (Multimer 2002). These boards were temporarily taken over by the Ministry, which appointed its own supervisors. This takeover was met by protest by trustees, parents, and unions, who argued that any further budgetary cuts would seriously harm children’s education.

Separate School Boards

In Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario, separate school boards operate along with public school boards. are denominationally based and generally represent schools that are associated with the Catholic faith, although a handful of Protestant school boards do exist. Separate school boards have their roots in the British North America (Constitution) Act of 1867, which provided some protection for denominational schools that existed prior to Confederation. The purpose of the act was to protect and prevent provincial governments from tampering with denominational schools that existed in Upper and Lower Canada prior to Confederation (at the time, entirely Protestant and Catholic, representing the English and French) and to protect minorities living in each part of Canada (Protestants in Lower Canada, Catholics in Upper Canada). The Protestant school boards in English Canada largely moved into the secular school system.

Newfoundland and Quebec, which both had denominational schools systems, made constitutional amendments to eliminate denominational schools in the late 1990s, with Quebec moving to French and English school boards. Manitoba eliminated constitutionally protected denominational schools in 1890. See Box 4.2 for a discussion of some of the debates surrounding faith-based schools and funding.

Box 4.2 – Funding of Faith-Based Schools

As shown in Table 4.1, provinces west of (and including) Quebec fund private/independent schools to some extent. And, because many private schools are religiously based, these provinces are partially funding faith-based schools provided they meet certain criteria, like following provincial curricula and being staffed by provincially certified teachers.

Debates have surfaced in Ontario over the way the British North America Act is used in modern educational practice. Critics have argued that the way the act is implemented serves to privilege the Catholic faith over others (see Magnuson 1991 for an overview). In Ontario, for example, no funding is given to private schools (many of which are faith-based), while the Catholic school board is publicly funded. In other words, the only faith-based schools that get funding in Ontario are those belonging to the Catholic school board, which is entirely publicly funded. In Atlantic Canada, where no independent schools receive public funding, Catholic schools are not funded either.

Other faith-based schools in Ontario (which do not receive funding) have argued that it is unfair to seemingly privilege the Catholic faith over others. They have fought back with legal challenges and created a lobby group that advocates for the funding of faith-based schools that meet provincial guidelines. The group, Public Education Fairness Network, comprises members from the Armenian, Hindu, Jewish, Muslim, and Sikh communities. They argue that the Ontario school system is not a secular one, by virtue of the fact that it funds Catholic schools, and that this funding should be extended to the remaining 53 000 students (or 2 percent of all students) who attend independent schools in Canada.11

In the late 1990s, Arieh Hollis Waldman brought a case before the United Nations Human Rights Commission, which dealt directly with the matter of public funding of non-Catholic religious schools. He argued that he wanted to provide his children with a Jewish education, and as a result would experience financial hardship—a hardship he would not experience if he wanted to provide his children with Catholic education. He argued that this practice was discriminatory and violated the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. In 1999, the UN Human Rights Commission ruled that although a provincial government is not obliged to provide funding to religious schools, if it does, it should then provide funding on a nondiscriminatory basis, without preference to certain religions. In 2007, the issue of funding non-Catholic religious schools made headlines again during the Ontario provincial elections, when Conservatives, then led by John Tory, made the funding of faith-based schools an election issue, promising to extend funding to such schools if elected. Dalton McGuinty, whose Liberal Party won that election, was strongly opposed to extending funding to such schools.12

Alternative Schools

The term very broadly refers to a school that differs somehow in its delivery of education from mainstream public schools. In many provinces, alternative schools exist within the public school system. In general, alternative schools emphasize particular languages, cultures (e.g., Aboriginal), or subject matter (e.g., arts), or they use a specific teaching philosophy. Often, alternative schools at the high school level are geared specifically toward children and youth who are deemed to be at a high risk of dropping out of school. For example, the alternative school programs in British Columbia and Quebec are mostly dedicated to this population and often have classroom setups, schedules, and curricula that are modified to accommodate this particular group of young people. Many alternative schools also emphasize small class sizes and year-round programming.

In Alberta, for example, publicly funded and administered alternative programs specialize in fine arts, French immersion, German, hockey, science, and Montessori. Montessori is a teaching philosophy developed by Italian educator Maria Montessori in the late nineteenth century that focuses on learning through child-centred and child-led experiential learning and by the natural development of children’s learning through pursuing their interests, rather than formal teaching practices. Montessori schools are generally oriented toward young children. In Ontario, a wide variety of alternative schools are offered by the district school boards, particularly in urban centres like Ottawa and Toronto (see Box 4.3).

Box 4.3 – Alternative Schools in the Toronto District School Board

Serving over a quarter of a million students each year, the Toronto District School Board is the largest in the country and the fourth largest in North America.13 To accommodate the diverse learning needs of the students in this district, several alternative schools are offered at the elementary (19) and secondary level (22).

As stated on the TDSB website:

TDSB Alternative schools offer students and parents something different from mainstream schooling. Each alternative school, whether elementary or secondary is unique, with a distinct identity and approach to curriculum delivery. They usually feature a small student population, a commitment to innovative and experimental programs, and volunteer commitment from parents/guardians and other community members. While the schools offer Ministry approved courses, these courses are delivered in a learning environment that is flexible and meets the needs of individual students.

In all alternative secondary schools students complete credit courses. Courses may be delivered through large group instruction, smaller co-operative groups, an independent study program, or other forms of learning that are negotiated with the teachers. Programs and program delivery models vary from school to school. Each school’s small student population typically includes a variety of ages and grade levels and provides a nurturing environment for students who benefit from having staff know them individually. Different secondary schools begin at different grades and offer different pathways where “success is the only option.”

Each alternative school, whether elementary or secondary, is a school of choice and has its own distinct culture. With such a wide range of alternative schools representing a host of different program delivery models, it is important for students and their families to visit a variety of alternative schools before choosing one that best meets their needs.”14

Many alternative secondary schools within the TDSB are focused on engaging students who are at a high risk of dropping out, or have dropped out in the past. An alternative program for lesbian, gay, and transgendered youth is housed within the OASIS alternative school, which also has programs for youth interested in skateboarding and street art. Other secondary alternative schools in the TDSB focus on experiential learning, creative arts, or university preparedness, and many also strongly emphasize the democratic student-inclusive decision-making processes that greatly inform their institutional philosophy.

At the elementary school level, the TDSB offers alternative schools generally all of which emphasize fostering strong linkages among students, school staff, parents, and the wider community. In terms of specific specializations, among the many alternative elementary schools in Toronto, there are those that focus on Africentric education (discussed in Chapter 5), social justice, and holistic and experiential learning.

Source: From Toronto District School Board website “Alternative Schools” http://www.tdsb.on.ca/_site/viewitem.asp?siteid=122& menuid=490&pageid=379.

Charter Schools—A Special Case of Alternative Schools

are special types of alternative schools that are semi-autonomous, tuition-free public education institutions that are unique in that they organize the delivery of education in a specialized way that is thought to enhance student learning. Currently in Canada, charter schools exist only in Alberta, and have been part of that province’s education system since 1994. Charter schools deliver the provincially mandated curriculum in a unique way that is spelled out in its charter, which is a formal agreement between the administration of the charter school and the minister of learning.

Charter schools provide basic education in a unique, different, or “enhanced” manner that characterizes the charter school in its own unique way. One major difference between charter schools and other alternative schools is that the governance of charter schools is undertaken by members of the charter board instead of the local school authority or district. The charter board typically comprises parents, teachers, and community members, unlike the governance of other public schools, which is undertaken by officials elected by public ballot.

While the types of charter schools in Alberta vary considerably, they all share the following characteristics (Alberta Learning 2002):

- they must provide access to all students, where space and resources permit;

- they must have a written charter that describes unique manner in which the school will deliver education and what student outcomes are intended;

- they must follow the Alberta Learning curriculum;

- they must not be affiliated with any religious faith;

- they must be accountable to the minister of learning and demonstrate that the mandates of their charter are being realized and that improved student learning has occurred;

- there is a minimum enrolment of 100 students;

- they must specialize in a particular educational approach or service that is designed to meet the needs of a particular group of students; and

- they may not charge tuition fees.

Charter schools are unique in that they can bypass district school boards and report directly to the province. Therefore, charter schools have much more flexibility than regular public schools. Flexibility in the governance of the school and the autonomy that the school has from the regular public system are also features of charter schools. They manage their own funding and hire their own (Alberta-certified) teachers. Charter schools in Alberta do not have permanent status and are renewed only when they have been evaluated as successful by the province.

In 2011, there were 13 charter schools in Alberta. Table 4.3 lists their names, locations, and specializations.15 As reported in the table, 9 of the 13 charter schools are in large urban centres in Alberta. The charter schools in Calgary are much larger and comprise 83 percent of the enrolment of students in charter schools in Alberta (Alberta Education 2011).

Table 4.3 Characteristics of Charter Schools in Alberta

| Name | Location | Focus |

| Almadina Language Charter Academy | Calgary | English as a Second Language |

| Aurora Charter School | Edmonton | Traditional education |

| Boyle Street Education Centre | Edmonton | At-risk youth |

| Calgary Arts Academy | Calgary | Arts immersion curriculum |

| Calgary Girls’ School Academy | Calgary | Leadership in young girls |

| Calgary Science School | Calgary | Inquiry-based, technology-rich |

| Centre for Academic and Personal Excellence (CAPE) | Medicine Hat | Academically capable under-achievers |

| Foundation for the Future Charter Academy | Calgary | Academic excellence and character development |

| Mother Earth’s Children’s Charter School | Stony Plain | |

| New Horizons Schools | Ardrossan | Gifted education |

| Suzuki Charter School | Edmonton | Academics enriched with music |

| Valhalla Community School | Valhalla | Rural leadership |

| Westmount Charter School | Calgary | Gifted education |

Charter schools have been contentious in Canada and elsewhere. Supporters of charter schools argue that such schools provide much-needed flexibility within the public system and give parents more choice about where they can send their children, without the burden of tuition fees. The flexibility in the delivery of the curriculum is also considered an advantage for students who can benefit from the unique approaches adopted by charter schools, such as students for whom English is a second language, gifted students, or at-risk youth. Supporters also argue that because charter schools are accountable to the province, they can be renewed only upon demonstrating that their charter mandates have been met. Such accountability helps ensure a high-quality education. Supporters of charter schools have also argued that competition with the regular public schools may also place pressure on public schools to improve, if they must compete with charter schools for students.

Opponents of charter schools, however, argue that such schools dismantle the public school spirit of having a common core of education for all. As curriculum in charter schools is delivered in special ways, students will receive different education overall from students in regular public schools. Opponents also argue that charter schools will encourage a to develop, where only students from privileged socioeconomic backgrounds will benefit from charter schools as such parents are characteristically more likely to try to form a new charter school. And because charter schools are small, there is only limited availability for students, which raises concerns about equity and fairness around access. Critics of charter schools argue that instead of improving the quality of traditional public schools indirectly through pressure and competition for students, the presence of charter schools actually discourages the reform of public education, instead encouraging parents to create “niche schools” that serve only special interests (Kuehn 1995). A final major criticism of charter schools has to do with its governance structure. Because charter schools are publicly funded, critics argue that their governance structures should be publicly elected, instead of appointed from within. See Table 4.4 for a summary of these arguments for and against charter schools.

Before you open the following panels, brainstorm the points in favour and against Charter Schools.

Charter schools also exist in similar forms in the United States, England, and Wales (“academies”), Sweden (“free schools”), and Chile (“voucher schools”). While New Zealand does not have “charter schools” per se, massive educational reform in the late 1980s resulted in an entire education system comprised of self-governing schools that operate in a similar manner to charter schools.

Private Schools

In general, are schools that are owned and operated outside of the public authority (Magnuson 1993). In Canada, private schools often do not receive any government funding and instead charge tuition fees. Because education is a provincial matter, however, the funding of private schools varies across Canada. In British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, and Quebec, some funding is given to private schools, provided they meet a variety of conditions, such as employing accredited teachers and teaching the provincial curriculum. Alberta provides the largest funding of private schools in Canada, funding up to 70 percent of the per student amount.

The regulation of private schools varies greatly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Those that partially fund students require that students meet a number of conditions, while those that do not receive funding are not subject to monitoring. In Ontario, the private schools are neither funded nor monitored, except at the secondary level in the case where the school is offering credits toward the Ontario Secondary School Diploma.

Around 7 percent of all school-aged children in Canada attend private schools, which has grown slightly from 1994 when the figure was around 4.5 percent (Lefebvre, Merrigan, and Verstraete 2011). The numbers, however, vary considerably among the jurisdictions. Around 10 percent of all school-aged children in Quebec are in subsidized private education. In British Columbia, the total percentage of school-aged children in subsidized private education is around 9 percent, compared to just under 5 percent in Alberta and around one percent in Saskatchewan (Lefebvre, Merrigan, and Verstraete 2011, citing Marois 2005). See Box 4.4 for a discussion of private education in Quebec.

Private schools add to the range of school choice that parents have around the educational options available to their children. Private schools, unlike public schools, however, often restrict access based upon admission criteria, which often includes demonstrated academic ability but may also include religious affiliation and even ethnic background (Magnuson 1993). Many private schools can be classified as associated with a particular religious affiliation or be academically oriented. Less often, private schools focus on a particular activity, such as ballet or athletics.

In Canada, the best-known private school is Upper Canada College, which is a boys’ school located in Toronto that has been in operation since 1829. Upper Canada College has among its alumni several lieutenants governor, premiers, and mayors. The school has a reputation for being the school of choice for wealthy and influential Canadians, having tuition fees of around $30 000 per year.

Home Schooling

In Canada, home-based learning, or , is permitted in all provinces and territories. In such arrangements, children do not attend school, but are educated at home, usually by a parent. Because each province and territory has its own Education Act, the regulations around home schooling vary by jurisdiction. In the majority of jurisdictions home schooled students must be registered with the department of education. In Saskatchewan, parents must apply to the local school authority for permission to home school their children.

Funding for home schooled children also varies considerably by jurisdiction, with the majority offering no funding to parents who home school. Notable exceptions are British Columbia, which funds $250 per home schooled child if that child is registered with the public school district, and Alberta, which gives 16 percent of the basic per-pupil amount directly to the parent. In some jurisdictions, home schooled students registered with the local school district have access to textbooks, learning materials, and equipment.

While home schooled children typically follow provincial curricula, an alternative approach to home schooling is called unschooling, a term coined by home schooling advocate John Holt (Holt 1981). Holt believed that the schools system was fundamentally flawed, and therefore heavily endorsed home schooling. He believed, however, that to replicate a classroom experience in the home would be to replicate the flaws in the present system. He believed that children are natural students possessing great curiosity and are eager to learn when they are free to pursue their own interests. is home-based education without curriculum, schedules, tests, or grades. The approach is entirely child-led. Topics are pursued as children show interest in them.

It is not known how many children are “unschooled” in Canada as they would usually be classified as home schooled.

French-Language Programs

The Canadian Charter guarantees parents the right to educate their children in their first language if it is English or French. French-language schools are present in every province and territory, and in order to attend a child must have at least one parent who is a native French speaker.

programs are for students whose first language is not French and is available in all jurisdictions, except New Brunswick. All classes are taught in French except for English. The goal of French immersion education is to develop linguistic excellence in the French language. In New Brunswick, changes in 2008 resulted in the termination of French immersion programs, which were replaced by intensive French instruction for all anglophone students beginning in Grade 5.

French immersion is widely supported because it promotes bilingualism. Some critics, however, have argued that French immersion actually promotes streaming of children. Willms (2008) found that French immersion students differ from English instruction students in a variety of important ways. French immersion students tend to be from significantly higher socioeconomic backgrounds, less likely to be male, less likely to have a learning disability (or be in special education), and have better performance on standardized tests. These differences are not the outcome of French immersion per se, but rather factor into the selection of students into such programs. Because French immersion programs are academically challenging, higher-ability children are more likely to be enrolled in such programs, while children who struggle in school would be discouraged from enrolling. Children in French immersion also come from higher socioeconomic backgrounds and are more likely to have parents with university degrees, indicating that economic factors also play a role in who attends French immersion (Worswick 2003).

International and Offshore Schools

Not all Canadian elementary and secondary schools are physically located in Canada. There are schools in Antilles, China, Egypt, Ghana, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Singapore, St. Lucia, Switzerland, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, and United Arab Emirates that use the curriculum of one of the provinces in Canada. Provincial ministries inspect the schools, which offer credits toward Canadian secondary diplomas. These schools are not publicly funded. Such schools are English speaking and often cater to globally mobile professional families (Hayden and Thompson 2008).

Offshore schools is a term that has been given to a new group of schools that follow the British Columbia provincial curriculum and employ teachers with B.C. teacher’s certificates. Such schools are mostly located in China. In 2002, British Columbia amended its Education Act to allow school districts to establish a “company” that would be able to offer for-profit schools outside of the country. At the time of writing, there are about 25 of these schools in operation. Offshore schools are often viewed as feeder schools for international students who wish to pursue post-secondary studies in Canada. By being educated in English and learning from a British Columbia curriculum, students in other countries can meet the requirements of universities across Canada. The tuition fees collected from offshore schools are also used to fund public education in British Columbia.

Post-Secondary Education in Canada

In Canada, post-secondary education is available at a range of government-supported and private institutions across the country. Such public institutions receive a substantial amount (50 percent or more) of their operating capital from the government and do not operate for a profit. Such institutions provide various credentials after completion of a program of study, such as degrees, diplomas, certificates, and attestations (Council of Ministers of Education, Canada 2008). While the ability to grant degrees has traditionally been solely the domain of universities, recent changes in some jurisdictions now allow colleges and private universities to award some types of degrees. According to the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada, a “recognized postsecondary institution is a private or public institution that has been given full authority to grant degrees, diplomas, and other credentials by a public or private act of the provincial or territorial legislature or through a government-mandated quality assurance mechanism.”18

There are 163 universities (public and private) in Canada, as well as 183 public colleges and institutes (Council of Ministers of Education, Canada 2011). Other institutions at the university (almost 70) and college (about 50) level have selected programs that meet the requirements of quality assurance at the level of the jurisdiction.

Post-secondary education in Canada is funded through a combination of municipal, provincial, federal, and private funds, which vary considerably by province and territory. Student tuition fees make up around 20 percent of the funding of post-secondary education.

Universities

Canadian public universities grant undergraduate degrees that range from three to four years, depending on the program of study, as well as some types of specialized diplomas. The word “university” is a legally protected term that can be applied only to institutions that meet the requirements outlined in the province or territorial University Act and which have been given such recognition by the regulatory body. Universities exist for the primary purposes of granting degrees and conducting research. The mission statements of universities emphasize non-economic objectives (Orton 2009) and the importance of the pursuit of knowledge.

As a major expectation of universities is the active research program of its academic community, an important element of academic life on university campuses is the principle of academic freedom. refers to the ability of researchers to teach, conduct research, publish, and communicate their academic findings and ideas without being at risk of losing their jobs or being otherwise penalized if their results are deemed controversial. In universities, tenure is a mechanism that ensures academic freedom for faculty members. refers to the process by which junior professors are found to meet the rigorous requirements of a given institution in the fields of teaching, research, and university service, and are granted permanent status wherein they cannot be dismissed without just cause. It has been argued that without this type of job security, academics may not pursue difficult or controversial topics and only research “safe” topics so as to not risk losing their jobs.

In addition to undergraduate degrees, many universities offer post-graduate study at the master’s and doctoral level. Master’s programs usually last one or two years, while doctoral programs are three years or longer. Universities can be divided into four general types: primarily undergraduate, comprehensive, medical doctoral, and special purpose (Orton 2009). universities are those that focus on undergraduate degrees (mostly bachelor of arts and bachelor of science degrees) and have few or no graduate program offerings. are those that are characterized by a wide range of programs at both the undergraduate and post-graduate levels, and also have a high degree of research activity. are those that have a wide offering of PhD programs in addition to medical schools. And are those that specialize in a particular field of study, awarding most degrees in a specific field.

Governance in Canadian Universities

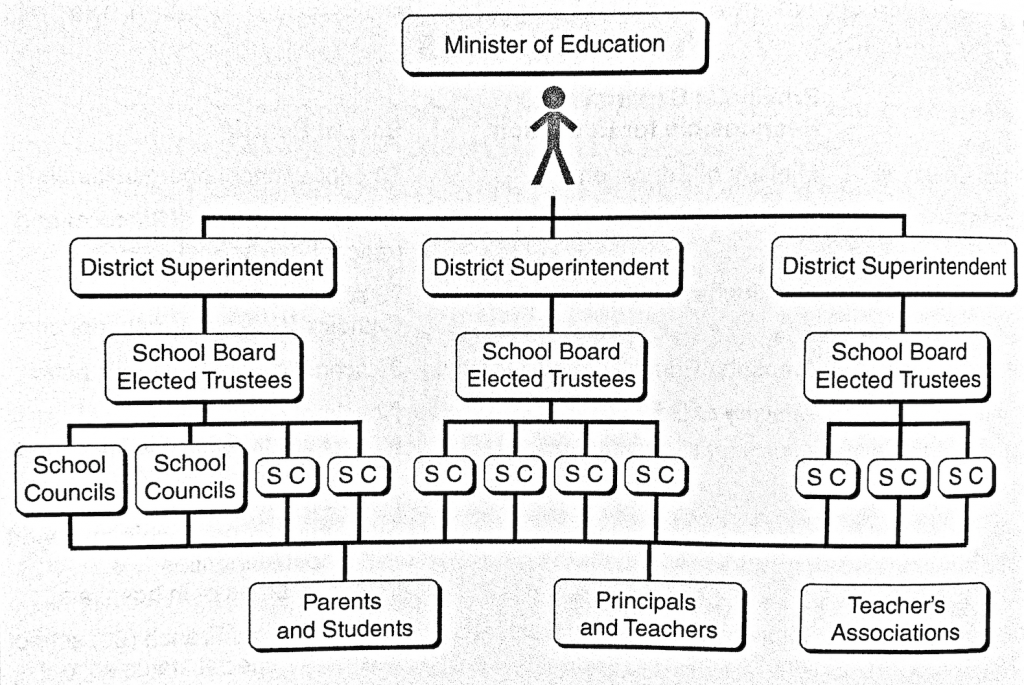

Canadian universities are considered autonomous, non-profit corporations (Jones, Shanahan, and Goyan 2001), which were created in jurisdiction-specific acts or charters. Public universities have much freedom in their governance as they are permitted to set their own admission requirements and program offerings. Interventions by the government are limited to concerns around fee increases and student funding (Council of Ministers of Education, Canada 2011). In terms of governance, public universities usually have two tiers of structure: a board of governors and a senate. The characteristic of having these two legislative bodies for the purpose of university governance is known as (Jones, Shanahan, and Goyan 2001). The vast majority of Canadian universities have adopted bicameralism since the 1960s, although the composition of the board of governors and senate can vary considerably between institutions.

Governing boards at a university tend to comprise persons of various backgrounds, including alumni (Jones 2002), although typically about two-thirds of the board are from outside the university. Faculty, students, and senior university administration (such as deans and the president) also typically sit on the board. The tasks of the board of governors are typically focused on issues related to policy and finances. In contrast, the major tasks associated with the university senate tend to be focused on academic matters, such as programs of study, admission requirements, appeals, and program planning. University senates are typically comprised of faculty, students, and senior university administrators. The rationale behind having a bicameralist system is historically rooted in the attempts to balance both academic and public interests within the formal organizational governance structure of the university (Jones 2002).

While the senate may be responsible for academic matters, and governing boards for administrative matters, a third source of decision making is found in the administrative structure of the university itself (Jones 2002). A university has a president who is appointed by the governing board. The job of the president is to attend to the day-to-day affairs of the institution and delegate authority within a structure of central administrative structure. In addition to the president, there are also at least two vice-presidents, deans of faculties, and heads of individual university departments. While there are many specific differences in the roles of each administrative position according to particular universities, one common role that the university president plays is serving as the official linkage between the university and the provincial government (Jones 2002). Also, the selection of higher-level administrative roles including the president and deans employs a participatory process, which includes a search committee comprised of various members of the university community, often including students (Jones 2002). Figure 4.3 represents a very general flow of decision making that is common to many Canadian universities.

Figure 4.3 Typical Flow of Decision Making in Canadian Universities

Faculty associations have also played an important role in university administration in the last few decades, with unionized and non-unionized faculty associations in place at most Canadian universities (Jones 2002). Such associations, particularly those that are unionized, have significant influence in the area of faculty salaries, workload, tenure, and promotion and academic freedom. Often, faculty associations include members other than full-time professors, including part-time faculty and librarians.

Student participation in the governance of universities increased in the 1960s and 1970s (Jones 2002), with student associations existing on all campuses. Usually university students are mandatory fee-paying members of at least one student association. The services that are offered by student associations vary according to campus, but can range from running businesses like campus pubs and restaurants, to printing a student paper, organizing student social activities and campus events, and monitoring institutional policies and practices (Jones 2002).

Colleges

There are literally thousands of colleges (sometimes called institutes) in Canada, ranging from those that grant degrees to those which provide specialized training in specific job-related skills, such as agriculture, arts, or paramedical training. Many private colleges that offer specific job skill training are called career colleges. Of all colleges in Canada, about 150 are recognized public institutions, with this figure including CEGEPS in Quebec (Council of Ministers of Education, Canada 2011). Colleges and institutes are legislated under provincial College Acts (or their equivalent, depending on the jurisdiction) and have a primary purpose of education (rather than research and education, as in universities). Mission statements of colleges usually emphasize economic objectives (Orton 2009).

In addition to , many other colleges can be classified as insofar as they offer a range of programs that vary from one to three years in duration (Orton 2009). In addition to these two sub-types of colleges, there are other that offer programs only in a specific area of study. As mentioned above, are another type of college operated on a for-profit basis and usually offer certificates and diplomas oriented toward professional development (Orton 2009), although some are gaining degree-granting status in specific programs of study. Another distinction between colleges and universities pertains to the concept of academic freedom. In colleges academic freedom is not guaranteed, and in career colleges it is essentially nonexistent (Orton 2009).

College Governance

College governance structures differ from those of the universities in that relatively few have a senate equivalent. In contrast, most have boards of governors with representation from students, teachers, the public, and jurisdictional governments. College governance (depending on the college) can also be influenced by business and industry representatives, who may sit on advisory boards or committees. There is often a more obvious and direct linkage between business interests and colleges governance (where there is a more direct connection with specific career-related training) than in universities. In contrast to universities, where the senate (or equivalent body) determines academic policy, in colleges, the provincial or territorial government authorizes degrees (if any), while the board is in charge of authorizing diplomas and certificates. Faculty councils may be present in colleges and institutes and serve in an advisory role, although such presence at a career college is very rare (Orton 2009).

Public and Private Post-secondary Education

The vast majority of universities in Canada are publicly funded (i.e., they receive government funding at the municipal, provincial, and federal levels for their operation), while just a fraction of the thousands of colleges in Canada are public institutions. , in contrast, do not receive public funding. In Canada, there are relatively few private universities, compared to the United States, for example. Many American universities, particularly those that are regarded as “ivy league” or very prestigious, are private in the sense that they do not receive government funding and generate their operating budgets from tuition fees and private donations. Tuition at private universities and colleges is generally much higher than at public institutions.

In Canada, there are relatively few private universities, although many colleges are considered private institutions. Many provinces passed legislation to allow private post-secondary institutions to grant degrees beginning in 2000. The introduction of these new laws was not without controversy, particularly in Ontario (see Box 4.6). Prior to this, private universities and colleges still existed, but the granting of degrees was limited to publicly funded institutions. In 1999, New Brunswick became the first province to pass a law called the Degree Granting Act, which allowed for-profit universities to operate in the province and to grant post-secondary degrees. In 2000, the Mike Harris government passed similar legislation in Ontario, which sparked much public debate. Harris argued that because many Ontario students were prepared to leave Ontario to attend American private institutions, offering similar private education within the province would retain these students. Harris also argued that because these schools have no public funding, there was no cost to the taxpayer. Critics, such as the Canadian Federation of Students, argued that allowing for-profit universities would create a two-tiered system that catered to the wealthy and that the for-profit institutions would be inaccessible to non-elites. Today, private degree-granting universities and colleges are established in Ontario, New Brunswick, British Columbia, Alberta, and Manitoba. The majority of these private institutions have religious affiliation.

Box 4.6 – The Arguments For and Against Private Universities

Cudmore (2005b) summarizes the arguments for and against private universities. First, during times of fiscal crisis and increased student demand, opening private universities creates additional student “spaces” that may otherwise not be available, and such spaces do not bear any cost on the government. The second argument for private universities stems from an outlook that views the current post-secondary system as fundamentally flawed. The introduction of competition from the private sector is one way to put the pressure on public post-secondary providers to increase accountability. The third possible advantage of permitting private universities is to attract business—particularly education entrepreneurs (such as the University of Phoenix and the Apollo Group, both major players in American private education)—to the local economy and stimulate economic growth. The final argument in favour of private universities centres on the issue of student choice; if students want to attend the degree programs offered by such institutions and pay the associated fees, this choice should be available. Otherwise, Canada may lose students to other countries where such choice is available.

There were many groups that were strongly opposed the new legislation allowing private universities, including the Canadian Union of Public Employees, the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Association, and the Ontario Public Service Employees Union. One of the major criticisms against private universities is the claim that they do not receive public money (Cudmore 2005b). Critics argue that private universities in the United States do in fact receive public money—up to 30 percent of the funds that are spent by such institutions are drawn from publicly subsidized student financial assistance programs or direct public subsidies (OCUFA 2000; OPSEU Online 2000). Subsidies include the ability to provide tax deductions to donors, and to claim tuition paid to such institutions as a tax deduction, for example. Critics also argued that attention to the neglect in the public system would decrease the perceived need for a private system. In other words, funding problems have led to decreased enrolments and program cutbacks, which have created a perception that there is a need for such a niche market, and fixing the problems in the existing system would negate the perceived need for private institutions.

Two more criticisms against private universities relate to their tuition cost and the quality of their educational product. Above, the concern that students had entered a two-tiered system in Canada was described. Related to this is the mounting student debt that a student attending such a private institution may incur over the duration of his or her degree program. Faculty associations have also argued that the values of public and private universities are not necessarily the same, with much of the staffing of private universities in the United States being drawn from part-time and contract faculty. The quality of the end product of a degree program has also been questioned by critics as there is no quality assurance from the province associated with the degrees being offered. Students are given the responsibility of deciding whether they believe that their completed degrees will be recognized by other post-secondary institutions or potential employers.

Currently, there are 17 private universities operating in Ontario, all which have religious affiliation.19

Post-Secondary Choices for Indigenous Students

While Indigenous students attend various post-secondary institutions across Canada, there are over 20 First Nations community colleges located throughout Canada as well as one university. Some of the First Nations colleges are in association with provincial universities and colleges.

Saskatchewan Indian Federated College (SIFC) was the first Indigenous-controlled post-secondary education institution in Canada that granted degrees. It was established in 1976 and is associated with the University of Regina. The mission of the university is

to enhance the quality of life, and to preserve, protect and interpret the history, language, culture and artistic heritage of First Nations. The First Nations University of Canada will acquire and expand its base of knowledge and understanding in the best interests of First Nations and for the benefit of society by providing opportunities of quality bi-lingual and bi-cultural education under the mandate and control of the First Nations of Saskatchewan. The First Nations University of Canada is a First Nations’ controlled university which provides educational opportunities to both First Nations and non-First Nations university students selected from a provincial, national and international base.20 (First Nations University of Canada website http://www.fnuniv. ca/index.php/mission. Used with permission.)

This is the only Indigenous-controlled university in Canada. There are three regional campuses in Saskatchewan and they are located in Regina, Saskatoon, and Prince Albert. Starting out with only nine students in 1976, the First Nations University of Canada now has a steady enrolment of about 1200 students per year, mostly at the undergraduate level, although some master’s programs have recently started to be offered. Students are attracted from all the provinces and territories.

Vocational Pathways

generally refers to a multi-year program of study that provides instruction in a skill or trade that leads a student to a job in that particular skill or trade. Such training can be acquired in secondary schools as well as at the post-secondary level. Public colleges and institutes as well as private colleges offer many programs that lead to vocational credentials. In addition to post-secondary institutions, workplace-based apprenticeship programs also exist. There are two ways that a person can enter an apprenticeship program: (1) by completing a pre-apprenticeship program through a college or vocational school, and then securing work with an employer to whom the apprentice is contracted to work for a fixed period of time, or (2) by securing work and then being sponsored by an employer into an apprenticeship program (Schuetze 2003).

The training of an apprentice combines work supervised by a qualified journey-person combined with in-class learning. Traditional trades training has been comprised of around 80 percent on-the-job training with 20 percent classroom teaching (often referred to as block release wherein apprentices are in school full-time for a period of four to six weeks). Apprenticeship training spans between 6000 and 8000 hours, which can take about three to five years to complete (seasonal work will take longer as the training can take place for only a limited time each year). After successful training, the apprentice takes an exam to become a certified journeyperson (Scheutze 2003). It should be noted that the apprenticeship model is slightly different in Quebec, where in-school training occurs before a person is formally registered as an apprentice (i.e., in the CEGEP system). The apprenticeship process then consists of on-the-job training and accumulated work experience (Schuetze 2003).

Apprenticeships are a relatively small part of the workforce in Canada, comprising only about one percent of the total labour force. The average age of a person in apprentice training is significantly higher than those in other post-secondary pathways—28 years of age (Scheutze 2003). There are around 150 registered trades in Canada, the majority of which serve the manufacturing, resource, and construction sectors of the economy. Trades and their requirements vary by province, although an interprovincial list of “Red Seal” trades has been established to allow for the competencies of a person’s trade to be tested so that they can practise their trade across Canada and are not limited to the jurisdiction in which their training occurred. There are currently 52 trades that are Red Seal, including baker, ironworker, machinist, hairstylist, cook, plumber, powerline technician, roofer, tilesetter, welder, and pipefitter.

Adult Education