Private: Education

Acknowledging the Past (Education)

Pre-colonization, Indigenous education was very different from formalized, European, classroom education. Indigenous education focused on practical skills in the natural environment, considering a spiritual worldview and a developing sense of one’s place in the community. Knowledge was passed to younger generations by family and Elders through storytelling and hands-on experience (Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples 2011). In recent research, Indigenous education has been distilled into the five Rs: respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility, and relationships (Kirkness & Barnhardt, 2001; Restoule, 2008 as cited in Tessaro et al., 2018). Adrian Wolfleg provides examples of traditional Indigenous education in the following video.

Indigenous Education Before and After Colonization – Youtube (6min12sec)

Indigenous Education Before and After Colonization – Youtube (6min12sec)

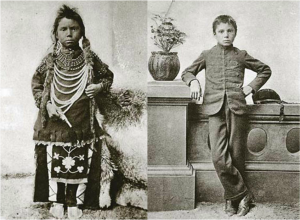

Toronto Metropolitan University was previously named Ryerson University, after educator Egerton Ryerson. The school’s name was changed in 2022, as awareness of Ryerson’s role in establishing residential schools became more widely acknowledged within the University community and the city. In this brief report, Egerton Ryerson (1847) outlined his vision for “Industrial Schools for the benefit of the aboriginal Indian Tribes,” what would come to be known as residential schools (p. 73). Although called “schools,” day schools and residential schools were actually sites of assimilation where children, some as young as three, were stripped of their families, communities, cultures, and languages. These “schools” were designed to train girls in domestic skills, and boys in farming or other technical skills, so they could be employed and assimilated into the settler context. Not only did the creation and continuation of residential schools create generational trauma and loss of culture, it also erased the potential of thousands of Indigenous children within their own lives, their families, and their communities, as well as Canada.

The Introduction to the Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee of Canada calls residential schools central to the government’s policy of the “cultural genocide” of Indigenous peoples, defining “cultural genocide” as: “the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group” (TRC 2015 p. 1). The report details this by continuing:

While the use of this terminology shocked many Canadians, TRC Chair, Justice Murray Sinclair, defended the use of this langauge, citing The International Convention on Genocide.

This is the ongoing shame of day and residential schools, and something of which the Canadian public and those of us in academe need to be conscious. The scope of problems created by day and residential schools over many generations are far too large to do justice to in this brief resource; however, the Truth and Reconciliation Committee investigated and recorded the voices of Indigenous survivors, publishing them in the volume The Survivors Speak. This is likely the most comprehensive, accurate and authentic place to seek information regarding residential schools.

Rather than assimilating Indigenous children into settler society, the loss of culture, language, and traditional ways of knowing disrupted Indigenous life, and can be seen as the root cause of many other issues facing Indigenous populations today, including substance abuse and mental health concerns. Residential school survivors and their families have been telling stories for generations about children who never came home. The government of Canada registered +4100 child deaths, and the fourth volume of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified 3200 deaths; however, it wasn’t until ground-penetrating radar on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School confirmed +200 probable unmarked graves on the school grounds in 2021 that the rest of Canada took notice. Investigations are ongoing at several other residential schools across Canada and in Ontario.

Crimes against children at residential school: The truth about St. Anne’s – The Fifth Estate Youtube (21min57sec)

Crimes against children at residential school: The truth about St. Anne’s – The Fifth Estate Youtube (21min57sec)

Because children in residential schools were often undernourished and housed in unsanitary conditions, disease was common (Bryce 1922). Dr. Peter Bryce was the Chief Medical Officer for the Department of Indian Affairs from 1904 to 1922. Early in his tenure, he was asked by the Department to investigate the high mortality rates among students at residential schools throughout the country. His 1907 report documents schools with 35% to 69% student death rates (as cited by First Nations Education Steering Committee 2015). Bryce stated that “we have created a situation so dangerous to health that I am often surprised that results were not more serious” (Bryce 1922). Among his recommendations were the improvement of ventilation and increased availability of medical resources, relocation of schools closer to students’ homes to reduce boarding, and a reduction of Church involvement in residential schools to support greater oversight by the government (including hiring and training of teachers) (Bryce 1922 p. 4). No government action was taken on the alarming results and reasonable recommendations from either his 1907 or 1909 reports. An accounting report from 1910 declares Dr. Bryce’s recommendations “inapplicable” due to financing some of the recommendations, as well as resistance from the Catholic Church (as cited by First Nations Education Steering Committee 2015).