Justice

Current Justice and Legal Issues

A country’s history informs its present. As outlined above, the clear intention over many centuries has been to eradicate and/or assimilate the Indigenous peoples of Canada and subsume their lands and territories into the colonized state. In recent years, we’ve seen evidence of blatant and systemic racism created by colonization still infiltrating all aspects of Indigenous life. One of the ways the general public sees this infiltration is through media stories of clear legal transgressions by white actors and/or police and/or legal systems visited upon Indigenous individuals due to racial profiling and entrenched racism.

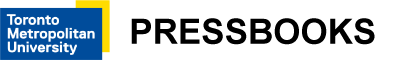

According to Census Canada, in 2021 Indigenous children under the age of 14 made up only 7.7% of children in the overall population; however, they represented 53.8% of children in foster care (Reducing the number of Indigenous children in care 2022).

This gross overrepresentation can be seen as both a continuation of the damage caused by residential schools and the beginning of a slippery slope into legal troubles for children and young adults. In some cases, being in foster care has also led to children’s deaths due to being taken in by people with malicious intentions, suicide, or abduction due to lack of supervision while in care (Sherlock 2017).

This gross overrepresentation can be seen as both a continuation of the damage caused by residential schools and the beginning of a slippery slope into legal troubles for children and young adults. In some cases, being in foster care has also led to children’s deaths due to being taken in by people with malicious intentions, suicide, or abduction due to lack of supervision while in care (Sherlock 2017).

Statistics Canada paints a grim picture in the Victimization of First Nations People, Métis and Inuit in Canada (2022) as a result of generational trauma. Although the numbers are falling among younger generations, about two in five Indigenous people experience physical or sexual violence before age 15; many of these incidents occur when these children are in the care of government agencies. While 4.2% of the non-Indigenous population were assault victims in 2019, the number doubled to 8.4% for Indigenous people. While 9.2% of non-Indigenous women experience sexual violence, this rate jumps to 26% for Indigenous women (Perreault, 2022).

Statistics Canada paints a grim picture in the Victimization of First Nations People, Métis and Inuit in Canada (2022) as a result of generational trauma. Although the numbers are falling among younger generations, about two in five Indigenous people experience physical or sexual violence before age 15; many of these incidents occur when these children are in the care of government agencies. While 4.2% of the non-Indigenous population were assault victims in 2019, the number doubled to 8.4% for Indigenous people. While 9.2% of non-Indigenous women experience sexual violence, this rate jumps to 26% for Indigenous women (Perreault, 2022).

Although traditionally women were highly respected in Indigenous societies, the same could not be said of European women during the time of colonization; they were generally perceived as inferior to men (Boose, 1991). The expansion of this perception to Indigenous women through colonization led to Indigenous women being doubly disadvantaged: they were not white and they were women.

This racist, misogynistic view has perpetuated over centuries, leaving young Indigenous women vulnerable to even harsher victimization, including human trafficking. The Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) produced a report on Trafficking of Indigenous Women and Girls in Canada (Roudometkina & Wakeford, 2018) that paints a tragic portrait. According to their research, Indigenous women account for 50% of domestic human trafficking victims in Canada, and many of them are under 18.

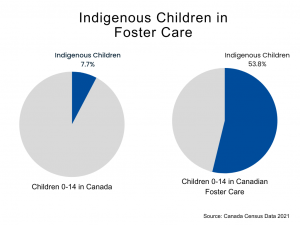

The cultural disruptions caused by both residential schools and the sixties scoop, accompanied by discrimination within the judicial system have led to a gross overrepresentation of Indigenous people in Canadian prisons. While Indigenous people make up less than 5% of Canada’s population, in 2000 they accounted for just over 17% of the prison population, and by 2020 they accounted for over 30% (Office of the Correctional Investigator 2020). Indigenous women make up a shocking 48% of prisoners in Canadian prisons, due in part to mandatory prison sentences (Major 2021).

What must also be considered with these high incarceration rates are the roles of the police and judicial systems and the rampant prejudice of some officers. For instance, since 1976, numerous cases have been reported of Saskatchewan police officers driving men into the prairies on winter nights, sometimes taking their jackets, and leaving them to walk home; often they do not survive (Carlton 2022). In 2016, Colten Boushie was shot by Gerald Stanley on Stanley’s farm in rural Saskatchewan; the second-degree murder charge was downgraded to manslaughter, and the all-white jury acquitted Stanley of the charges (Roach 2020). A 2020 study by CTV News revealed that Indigenous people accounted for 38% of police shooting deaths in Canada, again a gross overrepresentation given the percentage of the population (Flanagan 2020). Also in 2020, RCMP officers launched an unprovoked assault on Chief Allan Adam of Fort Chipewyan First Nation in a parking lot (Cecco 2020). These, and many similar incidents, point to the police as the frontline in a justice system that frequently supports systemic racism.

What must also be considered with these high incarceration rates are the roles of the police and judicial systems and the rampant prejudice of some officers. For instance, since 1976, numerous cases have been reported of Saskatchewan police officers driving men into the prairies on winter nights, sometimes taking their jackets, and leaving them to walk home; often they do not survive (Carlton 2022). In 2016, Colten Boushie was shot by Gerald Stanley on Stanley’s farm in rural Saskatchewan; the second-degree murder charge was downgraded to manslaughter, and the all-white jury acquitted Stanley of the charges (Roach 2020). A 2020 study by CTV News revealed that Indigenous people accounted for 38% of police shooting deaths in Canada, again a gross overrepresentation given the percentage of the population (Flanagan 2020). Also in 2020, RCMP officers launched an unprovoked assault on Chief Allan Adam of Fort Chipewyan First Nation in a parking lot (Cecco 2020). These, and many similar incidents, point to the police as the frontline in a justice system that frequently supports systemic racism.

The Federal Government established a task force in 2016 to investigate Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) and produced its report, Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, in 2019. After hearing from 2,380 survivors and family members of missing and murdered women, girls, and people who identify as 2SLGBTQQIA, echoing the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation report, the MMIWG report also consciously used the word genocide. It suggested that about 1,200 Indigenous women and girls went missing or were murdered between 1980 and 2012; however, the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) suggests the number is closer to 4,000. Given Indigenous mistrust of policing, some disappearances were unreported; given the history of the police and RCMP with Indigenous peoples, some reports were ignored. The documentary series Taken documents some of these stories, and includes links to information and police resources for reporting.

The Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) produces an annual scorecard of progress in implementing the Reclaiming Power and Place report’s 231 Calls for Justice directed to governments, social services, and various institutions. Their 2022 MMIWG2S Federal Action Plan: Annual Scorecard details how little action has been taken. While the Government has allocated $2.2 billion, it is unclear if or how these funds are being spent; this lack of transparency makes it difficult to ascertain progress. Reviewing eight general areas, the report suggests that little to no progress has been made, and that none of the actions has been fully realized.

Bernard Richard, a lawyer and politician, has stated that due to the effects of residential schools and the sixties scoop, Indigenous foster care requires much more funding than non-Indigenous foster care. “The intergenerational trauma has to be addressed—it’s significant and it won’t go away on its own. It has resulted in addiction and alcoholism and it has led to broken families, and sometimes physical abuse and sexual abuse” (Richard as cited in Sherlock 2017 para. 34). He also suggests that Indigenous child welfare should include culturally appropriate practices (Richard as cited in Sherlock 2017). Raven Sinclair states that “Sadly, the involvement of the child welfare system is no less prolific in the current era…the “Sixties Scoop” has merely evolved into the “Millennium Scoop” (Sinclair 2007 as cited in Sixties Scoop 2009). Solving the challenge of the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in foster care will go a long way to avoiding some of the problems Indigenous adults face.