Health

Current Healthcare Issues

According to the 18th Call to Action from The Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, “the current state of [Indigenous] health in Canada is a direct result of previous Canadian governmental policies, including residential schools” (Truth and Reconciliation Commision of Canada: Calls to Action 2015). It is necessary to recognize the generational and collective traumas of the history touched upon here, before attempting to understand the current uneasiness that exists between many Indigenous individuals and contemporary Canadian medical institutions when we look at the Toronto context. According to a 2010 Environics Study, two-thirds of Indigenous residents of Toronto say they are either directly or indirectly affected by residential school experiences (as cited in Toronto’s First Indigenous Health Strategy 2016-2021 2016).

The Government of Canada lists the Social determinants of health and health inequalities – Canada.ca as:

|

Income and social status |

Employment and working conditions |

Education and literacy |

|

Childhood experiences |

Physical environments |

Social supports and coping skills |

|

Healthy behaviours |

Access to health services |

Biology and genetic endowment |

|

Gender |

Culture |

Race / Racism |

It also acknowledges health inequalities for reasons of genetics, location and availability of nutritious food, personal choices (e.g., drinking, drug use, lack of exercise, etc.), and systemic inequities (Government of Canada, 2022).

A City of Toronto report titled Developing the Toronto Indigenous Health Strategy (2015) acknowledges that:

Indigenous people living in Toronto face a disproportionate burden of social challenges across the known determinants of health as well as barriers in accessing health services. Indigenous people experience higher rates of poverty, unemployment, homelessness, involvement with child welfare, food insecurity and challenges within the education system – all contributing to poor health outcomes (McCaskill et al., 2011; NCCAB, 2013; Olding et al., 2014; Steward et al., 2013).

The disruptive history of colonization and residential schools have severely disadvantaged Indigenous communities (Kim, 2019). The recognition of what is now called the social determinants of health was already recognized by Indigenous societies before the World Health Organization and the Government of Canada developed these ideas.

The Social Determinants of Health from a First Nation Perspective – YouTube (13min37sec)

It wasn’t until the early 21st century that Toronto’s First Indigenous Health Strategy 2016-2021 was published (2016). Building on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), this jointly written report sought to address ways the Indigenous population of Toronto could develop and administer their own priorities and initiatives regarding health, housing, justice, and social programs. Based on the traditional Medicine Wheel, Toronto Indigenous Health Strategy’s Vision Wheel was created to help identify existing knowledge and services, to develop strategies for moving forward, and evaluate progress. The Vision Wheel considers Action, Vision, Knowledge, and Relationships among individuals, caregivers, families and the community. The report concludes with a call for additional Indigenous physicians and nurses, but also increased Indigenous representation in mainstream planning and support agencies (Toronto’s First Indigenous Health Strategy 2016-2021 2016).

The Our Health Counts Toronto reports were gathered by and for the Indigenous community in Toronto using respondent-driven sampling for a more accurate snapshot than data found by Statistics Canada and other government organizations. These reports document the general health of Toronto’s Indigenous population as well as documenting chronic health conditions of this population, often comparing statistics with the non-Indigenous population.

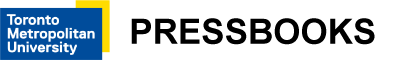

For instance, while 62% of the general population of Toronto rate their general health as good or very good, only 28% of the city’s Indigenous population rate their health in this range (Our Health Counts Toronto 2019). In terms of chronic health concerns, disease states include asthma, high blood pressure, and diabetes, the rates of which are many times higher in Toronto’s Indigenous population than the general population. For instance, rates of asthma among the city’s adult Indigenous population are three times higher than for the general population; rates of high blood pressure are three-and-a-half times higher; and rates of diabetes are nearly double (Our Health Counts 2018a). Additionally, 65% of Indigenous adults have chronic health conditions, with 38% experiencing multiple comorbidities, compared with only 15% of the general population (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014 as cited in Our Health Counts 2018b). Among children (14 and under), 20% had at least one chronic disease, with 18% experiencing two or more health conditions (Our Health Counts 2018b).

Oral health impacts general health, including diabetes and heart disease (Carstairs & Mosby 2020). Although policy around access is changing, the cost of dentistry can be a barrier to many low-income families, including Indigenous adults and children. While 85% of Canadians rate their oral health as good to excellent, only 54% of Indigenous adults in Toronto provide a similar ranking (Our Health Counts 2018d).

The Our Health Counts report on Reproductive and Sexual Health acknowledges that due to colonial interference, much Indigenous knowledge around reproductive health, birthing and parenting has been disrupted (Our Health Counts 2018e). In their report, First Peoples, second class treatment, Drs. Allan and Smylie (2015) suggest that the Indian Act, residential schools, forced sterilization and the outlawing of midwifery all contributed to this loss of Indigenous knowledge. Perhaps due in part to these disruptions, rates of gestational diabetes are almost twice as high in Indigenous mothers as non-Indigenous, leading to larger birth weights. Premature births were also more prevalent for Indigenous mothers, with 21% born prematurely compared to 8% of non-Indigenous mothers in Toronto; as a consequence, a higher percentage required neonatal care. Although 97% of Indigenous women indicated that they received their preferred prenatal care, it was not necessarily through the regular gynecological visits prescribed by Western medicine (Our Health Counts 2018e).

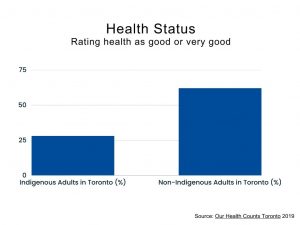

According to Statistics Canada, only 31% of Toronto’s Indigenous population report having good to excellent mental health, compared with 72% of the general population (as cited in Our Health Counts 2018c). Nearly half (45%) of Indigenous adults in Toronto have been informed by a healthcare worker that they have a mental health disorder.

According to Statistics Canada, only 31% of Toronto’s Indigenous population report having good to excellent mental health, compared with 72% of the general population (as cited in Our Health Counts 2018c). Nearly half (45%) of Indigenous adults in Toronto have been informed by a healthcare worker that they have a mental health disorder.

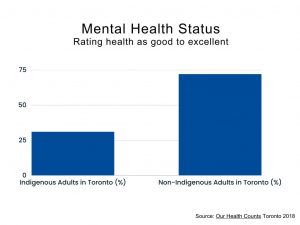

Anxiety disorders are three times higher than the general population at 24%; major depression is more than double the rate of the general population at 23%; and levels of post-traumatic stress disorder are at 11% compared with only 2% in the general population. High levels of mental health issues also lead to higher rates of suicidal ideation (50% of the adult Indigenous population) and attempted suicide (36% of the adult Indigenous population) in comparison to the general population (Our Health Counts 2018c). Post-secondary students are more prone to mental health issues than older adults; however, rates of depression, anxiety and substance use in this population are even higher among Indigenous students (Hop Wo, et al, 2020).

In Toronto, 23% of the Indigenous population identify as Two-Spirit (“niizh manitoag [two-spirits] indicates the presence of both a feminine and a masculine spirit in one person” Anguksuar/LaFortune, 1997 cited in Our Health Counts Toronto: Two-spirit Mental Health); however, their financial, physical and mental health is even more concerning than the rest of this population. Almost 40% experience gender discrimination, and 79% say this has prevented or delayed them in seeking help.

Mental health issues can lead to substance abuse issues too, as drugs or alcohol offer a type of self-medication for physical and psychological pain (Our Health Counts Toronto: Substance Use, 2018). Unfortunately, such self-medication offers only temporary relief. Substance abuse can lead to addiction, prolonging both personal and intergenerational trauma (RRC Polytech, 2022). Various studies have indicated that self-medicating behaviours start earlier in Indigenous populations, during peoples’ teens or preteens, making such addictions even more difficult to overcome (Spillane et al., 2020; Maina et al., 2020). Although many Indigenous people abstain from alcohol, those who do drink tend to drink heavily. Of great concern is the use of opioids and injectable drugs in this population, with 31% using non-prescription opioids on a daily basis and 19% of the Indigenous population using non-prescription IV drugs (Our Health Counts Toronto: Substance Use, 2018).