Nutrition and Food

Acknowledging the Past (Nutrition and Food)

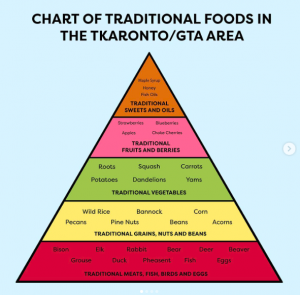

Traditionally, Indigenous populations lived off the land, gathering foods in season (such as wild rice, berries, and root vegetables), as well as fishing and hunting (game meats and fowl), often following herd movements. As colonizers advanced into the continent, exerting and enforcing legal and political powers, sometimes violently, Indigenous populations were forced from their traditional lands and practices. These actions, in addition to the imposition of Eurocentric cultural ideas, restricted Indigenous access to the good and varied nutritional sources accessible to previous generations. This resulted in a loss of knowledge about the sourcing, preparation, and consumption of natural foods derived from the environment.

As colonists overtook the land, building permanent settlements and eroding the natural environment, food sources would have become less accessible within the new city of York (incorporated as Toronto in 1834). By the mid-to-late 1800s, the implementation of reservations was added to treaty discussions, and Indigenous populations were often forcibly relocated to these remote parcels of land, well outside urban areas (Canadian Encyclopedia 2022). Colonialist farming methods required permanent settlements, quite different from the migratory lifestyle earlier Indigenous populations used for traditional food sourcing and agriculture. Reservations were small parcels of land that greatly limited hunting opportunities by restricting land area and disallowing hunters from following natural animal migrations off reserve.

In his book Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvations and the Loss of Aboriginal Life, James Daschuk (2014) exposes how the Government of Canada weaponized food to clear the plains of its Indigenous populations and make way for colonization. Food aid, guaranteed by treaty, was denied to coerce Indigenous populations onto reservations. Once on reservations, food was rationed, sometimes going to waste in storage before it could be distributed. Additionally, food aid provided by the government on reservations was stale, processed European-style food, rather than traditional Indigenous food. As Daschuk suggests, malnutrition led to thousands of deaths, and weakened Indigenous communities, making this population more prone to disease. While there may not be evidence of such events in Toronto, these historical facts make clear the colonialist thinking of the time.

Persistent hunger is a recurring theme in testimony from residential school survivors. The caloric, fat, and protein intake was woefully inadequate for growing bodies. The food that was available was of poor quality, often rancid, contaminated with insects, and led to outbreaks of food-bourne diseases. The lack of adequate amounts of good-quality food had obvious negative consequences on childhood development. Children were stunted and made more prone to health issues in adult life, including difficulties during pregnancy and childbirth, obesity, and developing type-2 diabetes (Mosby & Galloway 2017).