Land and Housing

Current Housing Issues

Housing is essential to maintaining good physical and mental health, providing a feeling of security, and a place from which to develop a sense of community. Urban Indigenous populations experience higher rates of precarious housing than non-Indigenous urban populations (Smylie et al, 2011 as cited in Our Health Counts).

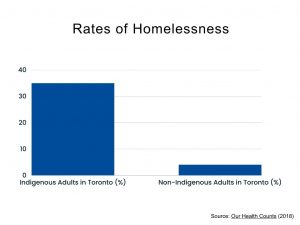

Research for the Our Health Counts (2018) Toronto report found that during the survey period, 35% of Indigenous adults in the city were homeless (defined as living with a friend or family, in shelters, or on the street) or precariously housed (defined as living in rooming or group homes). By comparison, only 4% of non-Indigenous residents had experienced similar precarity in the previous five years. According to a 2011 Toronto hospitals report, 14% of Indigenous mental health patients reported being homeless, compared with only 8% of patients from the general population (Toronto Central LHIM as cited in A Reclamation of Wellbeing: Visioning a Thriving and Healthy Urban Indigenous Community 2016, p. 7).

Research for the Our Health Counts (2018) Toronto report found that during the survey period, 35% of Indigenous adults in the city were homeless (defined as living with a friend or family, in shelters, or on the street) or precariously housed (defined as living in rooming or group homes). By comparison, only 4% of non-Indigenous residents had experienced similar precarity in the previous five years. According to a 2011 Toronto hospitals report, 14% of Indigenous mental health patients reported being homeless, compared with only 8% of patients from the general population (Toronto Central LHIM as cited in A Reclamation of Wellbeing: Visioning a Thriving and Healthy Urban Indigenous Community 2016, p. 7).

Of Indigenous adults who were stably housed, 44% reported that they were living in social housing, and only 4% owned their homes. The Indigenous population is also more mobile than the non-Indigenous population within the city, with 52% of adults having moved once in the year (compared with 14% of non-Indigenous residents), and 34% having moved three or more times in the year. Such mobility decreases one’s sense of stability within a home environment and community, as well as adding costs and complications (Our Health Counts 2018).

While 18% of Indigenous residents have always lived in Toronto, and 22% moved to Toronto from reservations, the majority, at 42%, moved to Toronto from another Canadian city. Most moved to Toronto for family or social reasons (40%), employment (33%), or education (26%) (Our Health Counts 2018).