Part 2: Pop-Up Shops and Stakeholders

Chapter 6: The Role of Pop-Up Shops in Community Development

Chapter Overview

This chapter looks at the potential role of pop-up shops within the area of community development. Communities can be defined in many ways, from geographic boundaries (e.g., neighbourhoods), shared identities (e.g., shared cultural heritage or beliefs) and increasingly, as virtual communities (e.g., social media platforms such as Facebook). A community is defined by both its members (or stakeholders) and their relationship to one another.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of the chapter, readers will be able to:

- Define community development.

- Understand the role of pop-up shops in contributing to community development.

- Identify different types of retail vacancy and the strategies used to handle retail vacancy.

Setting the Context

VIDEO

The following video helps to set some context about the considerations of landlords and BIAs (or community groups) who have been presented with the idea of offering short-term and/or reduced-rent lease agreements for pop-up shops as part of a strategy to revitalize a location with long-term vacancies.

1. Community Development and Streetfront Revitalization

The term community development can be used to describe a range of community-based interventions and their outcomes. It is typically seen as a grassroots (or ground-up) process through which communities seek to improve their collective well-being and quality of life. This can involve working together to improve health, reduce poverty, strengthen the local economy or address any range of social, economic, cultural or environment goals.

Community development is a collaborative process whereby the community takes responsibility for tackling issues of common interest. Development does not necessarily mean that growth needs to take place, rather development is used to refer to making changes within the community for the betterment of the community as a whole. Community development can therefore be seen as a vehicle for change. It needs to be planned and organized both by and for the community. Community development is often associated with concepts such as economic development, urban renewal and revitalization.

Community Development: the planned evolution of all aspects of community well-being (economic, social, environmental and cultural). It is a process whereby community members come together to take collective action and generate solutions to common problems. The scope of community development can vary from small initiatives within a small group, to large initiatives that involve the whole community. Regardless of the scope of the activity, effective community development should be:

- a long-term endeavour,

- well planned,

- inclusive and equitable,

- holistic and integrated into the bigger picture,

- initiated and supported by community members,

- of benefit to the community

- grounded in experience that leads to best practice.1

As many pop-up shops are located along streetfronts, this chapter will focus on how pop-up shops can contribute to the revitalization of traditional commercial strips in urban markets and the impact that this can have on the local community. We will look at the ways in which pop-up shops contribute to community building, the stakeholders in the community that are interested in and impacted by pop-up shops and the challenges facing pop-up shops in terms of translating short-term revitalization into long-term commercial vitality and vibrancy. We will explore three case studies of community-led pop-up shop initiatives from Canada, the US and Australia. An additional generic case study will highlight the challenges associated with transitioning pop-up shops from temporary to permanent use.

1.1 Identifying the Need for Streetfront Revitalization

Before we look at how pop-up shops can contribute to streetfront revitalization we need to identify the characteristics that define commercial blight along streetfronts. Why do streetfronts need to be revitalized? What are the signs of blight? When does the community become concerned? While the most obvious indicator of the need for streetfront revitalization is store vacancy, it is important to note that there are many indicators that may signal the need to engage in streetfront revitalization activities. For example, over time, the quality of the tenants along a streetfront may deteriorate, there may be increased criminal activity along the street or the streetfront may appear unkempt with buildings in need of repair. Pop-up shops can be part of the process of re-energizing streetfronts by temporarily occupying vacant spaces, engaging the local community in such efforts, and potentially becoming long-term tenants.

1.2 Store Vacancy

The ultimate sign of commercial distress is when a business goes through the process of closing and leaves behind a vacant property that is placed back on the market. When retail space becomes available, it is left up to the market to determine if there is enough demand to re-lease the space. Does anyone want to lease the vacant space? If so, at what cost, for what use and over what period of time? Rabianski (2002) describes three types of vacancy: frictional, cyclical and structural.2 The differences between these types of vacancy help illuminate the challenges and opportunities involved in turning a vacant space back to productive use again.

1.2.1 Frictional Vacancy

Frictional vacancy can be described as “the cost of doing business”. Frictional vacancy is inherent to a functioning real estate market, and is therefore not of any special concern to the store owner/landlord. An example of this would be a landlord securing a major retailer to take over an abandoned store, but the tenant being unable to open for many months due to the renovation and refit of the property. This space would be vacant from a consumer (and community) perspective, but not from the landlord’s perspective. This can be thought of as a form of transactional vacancy, whereby there is a firm commitment to occupy the space at later point in time. The vacancy is therefore simply part of the transition from one tenant to the next. Many frictional vacancies are extremely short-term as owner/landlords do not want their properties to sit empty without tenants paying rent.

1.2.2 Cyclical Vacancy

Cyclical vacancy occurs when a space is vacant as a result of a weakening economy. This indicates that the space would otherwise be in demand, however is not currently leased due to broader economic weakness in the area or region. While this is problematic from the owner/landlord perspective, the solution rests mostly in an economic recovery for the region. Such downturns in the economy impact the entire community.

1.2.3 Structural Vacancy

Structural vacancy is the most problematic and challenging to owners/landlords and the community. It is space that is not demanded in its current configuration, as it is either too large or small to be reasonably used and/or in need of major renovations and reconfiguration (or adaptive re-use of space such as converting some of the retail space to residential units). It often requires redevelopment and associated capital expenditure in order to be absorbed into the market. From a community perspective, this is a major issue as structural vacancy represents long-term vacancy and is typically associated with significant sustained commercial blight. Streetfronts with widespread vacancy, boarded-up properties and often absentee owner/landlords have numerous knock-on effects for the community and without intervention, can spiral down into extremely challenging revitalization projects that fall well beyond the bounds of grassroots interventions. In extreme cases, very high structural vacancy may involve the local government expropriating and demolishing properties as they prepare the sites for future development projects.

Table 6.1 Types of vacancy2

| Vacancy Type | Definition | Example |

| Frictional | The excess supply that allows the market to work efficiently; allows easy movement of space users from one place or space to another. | Clothing store lease expires; retailer decides to relocate to other end of the street; vacant space is filled a few months later by retailer looking to open up shop |

| Cyclical | The excess supply that occurs as demand for space declines due to economic and financial factors. Once demand for space increases, cyclically vacant space will be taken directly from the market. | Furniture stores closes on the streetfront as economy enters recession; dollar store moves in one year later as economy improves |

| Structural | The excess supply in the market that does not meet the needs of space users (i.e., a mismatch between the attributes of the space and the needs of the space user). Unlike cyclically vacant space, structurally vacant space will not be absorbed until it is rehabilitated and renovated. | Store sits vacant for four years; building is zoned for commercial use, but a new owner seeks to demolish the retail store and develop mid-rise residential condos with street-level retail |

Table 6.2 Prioritizing vacant property strategies3

| Vacancy Level | Neighbourhood Conditions | Goal | Priorities and Strategies |

| Lowest Vacancy | Vacancy rates: Relatively low | Retain current properties | Prevent vacancy |

| Property conditions: | Get properties reoccupied | Maintenance | |

| – Generally well preserved | Marketing | ||

| – Very few vacant lots | Increased code enforcement | ||

| Neighbourhood engagement: | Address commercial vacancy on neighbourhood borders | ||

| – High | |||

| Low Vacancy | Vacancy fates: Relatively low | Retain current properties | Prevent vacancy |

| Property conditions: | Get properties reoccupied | Marketing | |

| – Generally well preserved with some maintenance required | Increased code enforcement | ||

| Neighbourhood engagement: | Maintenance activities | ||

| – Relatively high | Repair and rehabilitation | ||

| Address commercial vacancy | |||

| Moderate Vacancy | Vacancy rates: Mid-level vacancies | Retain current residents | Demolition |

| Property conditions: | Prevent damage | Greening and vacant lot maintenance | |

| – Some open, dangerous and blighted properties | Boarding and securing | ||

| Neighbourhood engagement: | Increased code enforcement | ||

| – Organization exists but involvement tends to be relatively low | |||

| High Vacancy | Vacancy rates: Relatively high | Obtain control | Demolition |

| Property conditions: | Manage vacant lots | Large scale greening | |

| – Many blighted structures and vacant lots | Get dangerous properties demolished | ||

| Neighbourhood engagement: | |||

| – Low to non-existent |

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

- Which type of vacancy is the most challenging to work with and why?

- Are pop-up shops better suited to dealing with a specific type or level of vacancy?

- Who is responsible for dealing with streetfront vacancy?

2. How Can Pop-up Shops Contribute to Streetfront Revitalization Efforts?

Example

Pop-ups can offer an affordable and creative means to address many problems that challenged retail districts face. Small, temporary investments fostered by pop-up programs can help advance larger, more permanent investments or broader organizational or community goals.4

To learn more, please watch the following video about pop-up strategies to revitalize some of Detroit’s neighbourhoods.

Pop-up shops facilitate the temporary activation of vacant space. Given the role that consumption plays in our modern-day lifestyles, the revitalization of local retail and services is a crucial element of community development. As Smart Growth Americas note, pop-up shops can be part of a broader retail revitalization plan and strategy aimed to create diverse retail and build a “shop local” culture.

Maintain ‘pop-up’ locations to grow local start-ups and experiment with retail formats. As downtown values escalate, smaller businesses can find it difficult to locate affordable space, and small retailers such as artisan boutiques, may find it difficult to generate enough income from sales to justify a permanent storefront. Pop-up shops generate interest among shoppers while giving entrepreneurs the chance to test the waters or reach new customers. This strategy can be particularly useful in areas with several vacant storefronts.5

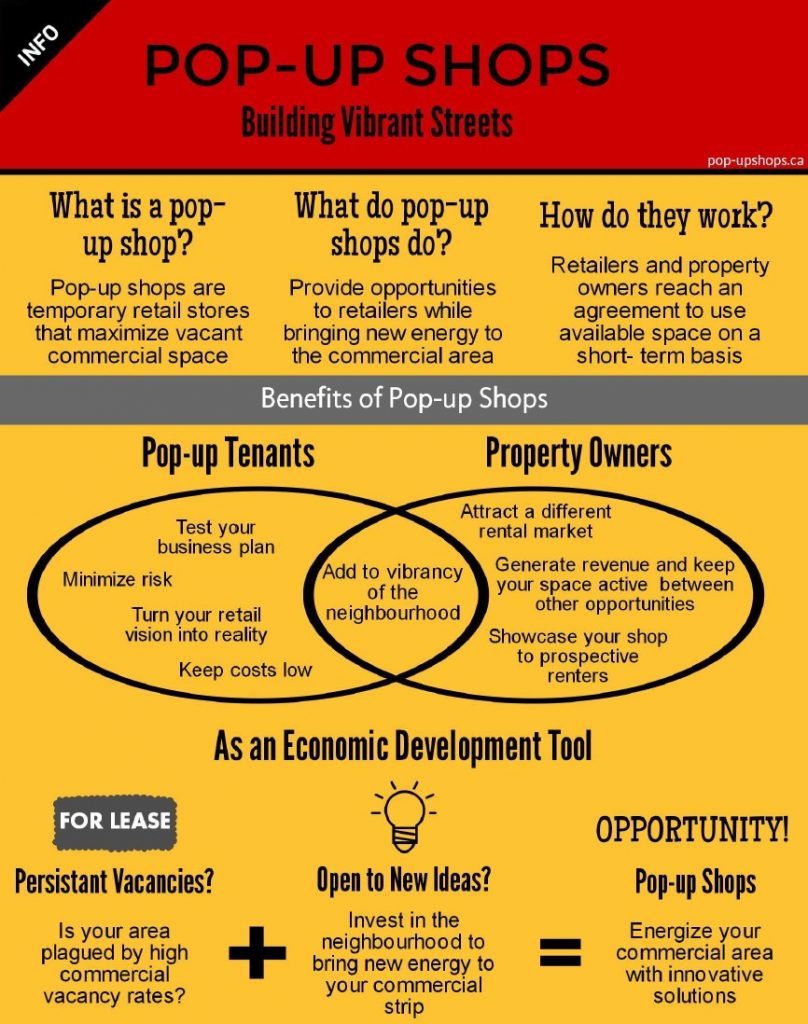

Figure 6.1 Benefits to Property Owners and Tenants in Building Vibrant Streets

Source: Danforth East Community Association

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

- Who are the community stakeholders and what are their interests in pop-up shops?

- What are the key benefits of pop-up shops to the community?

- Who should decide what type of pop-up shop is needed and/or allowed to operate?

- Are any members of the community negatively impacted by pop-up shops?

3. Pop-Up Shops and Sustainable Community Development

Traditionally, the standard measure of success in streetfront revitalization is the conversion of short-term vacancy into long-term leases. However, the widespread disruption that is taking place in the retail sector today is fundamentally challenging traditional retail business models. The concept of long-term retail lease agreements may no longer be a true metric of success in an environment that increasingly places emphasis on experiential as opposed to transactional retail space.

Pop-up shops represent a double-edged sword for the retail and real estate industries – whether we are looking at independent retail along streetfronts or major chain retail stores within major shopping centres. Pop-up shops provide tremendous opportunity to re-invigorate streetfronts and shopping centres, yet also contribute to the ongoing challenges that retail tenants and their landlords face in determining the need for retail space, its value and the best way to manage space.

From a streetfront perspective, the management issues are particularly acute due to fragmented ownership and the lack of contiguous spaces to manage. When you place these changing retail business models into a community development context it becomes even more challenging. As Frank and Smith (1999) note, community development is a tool for managing change, but it should not be used as a “quick-fix or short-term response to a specific issue within a community”. They go on to state that:

community development is about community building as such, where the process is as important as the results. One of the primary challenges of community development is to balance the need for long-term solutions with the day-to-day realities that require immediate decision-making and short-term action.6

However, there is a growing interest in tactical urbanism with guerilla urbanists engaging in a broad range of temporary revitalization projects, from art work on sidewalks to cleaning storefronts, with the assumption that such short-term projects will ultimately lead to long-term change.7 If pop-up shops are nothing more than temporary stop-gap measures, they are unlikely to create long-term externalities (or spin-off effects) for the community. However, despite their small scale, pop-up shops can be viewed as a catalyst for change and their success may prompt more substantive revitalization projects over the long-term.

While these small investments can have big impacts, pop-up programs are not an end-all be-all solution as a standalone initiative. When pop-up programs are integrated within a larger portfolio of investments or interventions, long-term change is more likely. Pop-up initiatives are especially well suited for collaboration that allow multiple actors to contribute to the change they want to see. Involving multiple partners at the local, city, region and state level when creating a larger vision for business district revitalization can help instigate additional investments. When pop-up is part of the vision, the momentum and excitement seeded by small investments and small projects help illustrate potential solutions and can help make the case to begin tackling larger opportunities and challenges.4

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

- What are the most important indicators of the long-term impact of pop-up shops on the communities in which they locate?

- What type of new measures of success could be used to evaluate the impact of pop-up shops?

- Is the success of pop-up shops measured by not needing them in the future?

The Case Studies

Danforth East Pop-Up Shop Project

Danforth Avenue is one of the City of Toronto’s major east-west arterials, running from Yonge Street in the west all the way to Scarborough in the east. It has long home to the trendy and affluent Greektown neighbourhood, but by 2012, there were segments of Danforth Avenue to the east that were showing signs of escalating retail vacancies.8 One specific group of residents, the Danforth East Community Association (DECA), decided to tackle the challenge proactively.

Starting out with the specific aim of increasing foot traffic along the eastern part of Danforth Avenue, from Monarch Park Avenue in the west to Main Street in the east, DECA decided to activate empty storefronts with pop-up retail that would attract local shoppers, generate activity on the street and provide spaces for entrepreneurial and start-up shops.

The Pop-up Project was officially launched in 2012, spurred on by an inspiring presentation from Marcus Westbury of the Renew Newcastle program in Australia. In 2013, in partnership with community agency WoodGreen Community Services and funder The Metcalf Foundation, the program hired two Economic Development Coordinators to keep up the momentum and drive the process forward.

Over the next five years, the team would: identify empty storefronts along East Danforth; engage with and encourage the participation of landlords; prepare available storefronts for pop-up tenants; and both invite and screen prospective pop-up retailers to join the program. Volunteers were also involved in every step, from marketing to screening of tenants.

The program started by offering free space for one month to retail pop-ups, but had limited success, so the decision was made to offer longer pop-up leases but with highly affordable rents. The model evolved into tenants paying $750/month in rent, along with 10% of sales beyond an agreed baseline.

Between 2012–2017, the Danforth East Pop-Up Shop Project saw:

- 32 pop-up shops launched

- 15 stores permanently leased

- 11 landlords’ participation (some owned multiple storefronts)

- decreased commercial vacancy rates (from 17% to just 6%)9

In addition, six small enterprises were incubated by the Pop-up Shops Project, including:

- Merrily, merrily

- The Handwork Department

- LEN Democratic Purveyors of Fine Art & Beautiful Things

- In This Closet (operated for three years but has since closed)

- Fa.real Custom Tees

- Looking Glass Adventures

Along the way, the organizers learned some valuable lessons. For example, programs like the Danforth East Pop-up Shop Project are best suited to neighbourhoods where storefront vacancies are 15%–20% and there is the opportunity to generate real excitement about the opening of new, local stores. An active residents’ association that took a strategic perspective of neighbourhood revitalization and focused on pop-ups as part of a larger initiative was an asset to the success of the project. Among the challenges was finding landlords willing to participate, since Toronto landlords receive a vacancy rebate for unoccupied space. Other challenges included figuring out how to work with existing retail businesses and engaging the community stakeholders in the revitalization initiative.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

- Why do you think that one month rent-free leases weren’t successful?

- Is it more effective to launch a pop-up retail program as part of a larger community revitalization strategy? Why or why not?

- Why would a vacancy rebate discourage landlords from participating in a pop-up retail project?

Art Enlivens Empty Storefronts in Seattle

For many of the early adopter pop-up programs, the arts and culture sector has provided the tenants, not the retail or artisanal sector. Storefronts Seattle, which was launched in 2010, is a case in point.10 By that time, downtown Seattle was dealing with a combination of factors that were causing storefront vacancies to escalate. A conversion of residential to commercial space on the back of the dot com boom meant that the downtown emptied out after working hours. The 2008 recession had dealt a blow to smaller businesses already struggling with the loss of a local market. Vacancies hit an all-time high of 20% at the end of 2010 and community stakeholders decided to take action.

Initially billed as a pilot project, Storefronts Seattle was spearheaded by a not-for-profit arts organization called Shunpike and the concept was to match artists and art groups with vacant storefront space. The idea was to create art installations that the public could view and enjoy through store windows, which is somewhat different from later programs that activated empty space with art galleries or studios.

In the case of Storefronts Seattle, the City of Seattle has played a constructive and supportive role, especially on a strategic level, participating in blue-sky thinking, brainstorming and working to identify economic development actions. Participating landlords made their spaces available on a month-to-month-basis, for a period of between three to six months, at a nominal rental of $1/month. Critically, tenants agreed that if the property owner secured a permanent tenant, they would relocate within 30 days – this ensured landlords did not miss any opportunities. Indeed, landlords have benefited from Storefronts Seattle directly, as 20% of the previously empty spaces were rented on long-term leases at full rents.

Artists and arts groups are required to submit a detailed proposal to Shunpike and these submissions are reviewed and selected by an independent panel. Successful projects, according to the submission criteria, are: compelling, viable and relevant.

In 2014, Storefront Seattle placed 50 individual artists in the greater Seattle area. But then things started to change. The economic climate improved, demand for space in the downtown picked up, and new development projects emerged. The net impact was that available vacant space became harder and harder to find. Storefronts Seattle is responding to the changing urban dynamic to focus on new opportunities: filling street-level vitrines in corporate offices with art displays, for example, and identifying spaces on the margins that remain unused.

Further Reading:

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

- What are some of the challenges with installing art in vacant storefronts, compared to activating empty spaces with artists’ studios or galleries?

- In other pop-up programs, providing space for free was unsuccessful. Why was free space viable for Storefronts Seattle?

- Are there other ways that the program can respond to an improving economic environment?

Renew Newcastle Inspires a Main Street Revitalization Movement

One of the most frequently cited and widely emulated pop-up initiatives is that of Renew Newcastle, which was launched in Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia in 2008. Not only did it spawn the revival of Newcastle’s deteriorating CBD, it also inspired a movement (e.g., Renew Adelaide, Pop-up Parramatta and Renew Townsville).

The global economic recession in 2008 was a death knell for Newcastle, which was already struggling with empty storefronts and businesses relocating to the suburbs. By that time, the city centre had some 150 empty stores and no new development. Projects that had been in the pipeline before 2008 were stalled or entirely scrapped by the recession.10

Renew Newcastle acts as an intermediary between temporary creative uses and the landlord. Inspired by projects that matched artists with vacant spaces, the initiative evolved with several important differences from similar programs elsewhere in the world:

- Barriers to both the artist and landlord are actively minimized. By focusing on liability insurance, tax and accounting support, and managing operating costs, the program makes it simple for both property owners and tenants to participate. For instance, tenants sign rolling 30-day licences, rather than complex lease agreements, and agree to vacate quickly if permanent tenants are secured.

- Tenants can be private or not-for-profit. Initiatives include: galleries and studios for artists; office spaces for emerging professionals like architects; and retail space for artisanal goods.

- Everything being sold is handmade. Whether it be art or professional services, participants sell their own services or products.

Using this approach, Renew Newcastle launched 40 new enterprises and initiatives in its first year alone.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

- Why would vacant buildings attract street crime, vandalism and violence?

- Why are business licences easier to implement than lease agreements?

- Why is the “handmade” requirement important for the program’s success?

Key Takeaways

In this chapter, you learned:

- how pop-up shops can be used as part of sustainable community development to enhance the vitality and viability of commercial strips

- how stakeholders involved in community development can leverage pop-up retail as part of revitalization efforts to reduce different types of commercial vacancy

- what types of benefits can be accrued by businesses and other community stakeholders through managed pop-up retail initiatives

Key Terms:

- Community Development

- Types of Store Vacancy (e.g., Cyclical, Frictional, Structural) and Property Vacancies (e.g., Low, Moderate, High)

Mini Case Study

Creating a vintage cluster to leverage intensifying residential population

As part of the city-wide trend towards downtown living and residential intensification, Blobsville was seeing a resurgence of interest in families buying houses and townhomes in the neighbourhood, which was traditionally characterized by small workshops: car mechanics, glass manufacturers and building suppliers. The small, older and blue collar community was serviced by a cluster of convenience stores, independent grocers and hairdressers. However, with residential growth, the local neighbourhood has slowly become more professional and affluent, showing an increasing interest in local, artisanal and upcycled shopping choices.

As the owners of the older stores and businesses have retired and moved on, and despite the high influx of residents into the neighbourhood, the number of streetfront vacancies has continued to increase. With it have come rising perceptions that the neighbourhood may not be safe, that there are too many people panhandling in front of empty buildings and the main street has an air of desolation. Prospective home buyers start to speak about the risk of urban blight on real estate prices if something isn’t done.

The local Business Improvement Area, which has recently been formed by the owners of local properties concerned about rising vacancies, decides to take action. They start by engaging with the local municipality’s economic development team and asking them to identify incentives for public space activation or storefront renovation, but none exist. They approach the local residents’ association and agree to partner on a pop-up retail program, based on the growing number of residents with disposable income. They convince three landlords with existing empty stores to provide short-term space at a lower-than-market rental rate.

Based on community consultation by the residents’ association, the pop-up program will focus on building a cluster of vintage clothing retailers. Research suggests there is strong demand in the neighbourhood for vintage clothing and accessories, as well as in the surrounding residential areas.

The pop-up program launches in June with much fanfare for three carefully screened small businesses specializing in vintage wear, supported by low and fixed rents, and a social media campaign driven by both the BIA and the residents’ association. The stores are set to the be open through the summer.

Unfortunately, by the end of the summer, all three pop-ups have closed and none will be signing longer-term leases with the landlords.

A debriefing by all of the stakeholders involved identified three major challenges that were not anticipated nor managed during the program:

- Each of the three pop-ups were located on different blocks along the same street.

- Street-based issues like panhandling and public consumption of alcohol impacted public safety.

- Shoppers consistently complained that two of the three pop-up stores were not selling truly vintage products.

Consider the following questions:

- Why did the three factors (above) so significantly impact the pop-up pilot?

- What measures could be put in place for the next pop-up program to mitigate these issues?

References

- Frank, F. & Smith, A. (1999). The Community Development Handbook: A Tool to Build Community Capacity. Human Resources Development Canada.

- Rabianski, J. S. (2002). Vacancy in market analysis and valuation. The Appraisal Journal, 70(2), 191-199.

- Michigan Community Resources (2013). Vacant Property Toolbox.

- Forsyth, M. & Allan, L.E. (2014). Pop-Up Program Development: Lessons Learned and Best Practices in Retail Evolution. University Center for Regional Economic Innovation, Michigan State University.

- Smart Growth America. (2015). (Re)Building Downtown: A Guidebook for Revitalization.

- Frank, F. & Smith, A. (1999). The Community Development Handbook: A Tool to Build Community Capacity. Human Resources Development Canada.

- AARP (n.d.). Pop-Up Demonstration Tool Kit.

- Gaber, B., KC, S., McLean, G., Morgan, G. & Vasic, M. (2013). Between Monarch and Main: An analysis of main street revitalization efforts in Toronto’s Danforth East neighbourhood. PLA1106: Workshop in Planning Practice, Geography & Program in Planning, University of Toronto.

- Stephenson, G. (2017, August 15). The Pop-Up Shop Project. Slide presentation to the City of Barrie.

- Cohlmeyer, E. (2013). Reimagining Vacant Storefronts: Exploring new models for the temporary use of space in Seattle, New York, Newcastle and Toronto.