Transcript of Simulation Walkthrough

Longhouse 3D (Re)Visualization: Guided Walk by Dr. Michael Carter (Edited Transcript)

Michael Carter: Thank you everyone for coming together to have a virtual walkthrough of our Longhouse experience.

We talked a lot about the fact that longhouses were representative of community-based environments and there were matriarchally controlled.

So each longhouse had its own family or extended family based on the matriarch’s lineage The village itself, whether it was two or three longhouses or a hundred longhouses were also controlled by the family matriarchs.

So it was very important to understand that community and family were a key part of Indigenous longhouse living. This was primarily based on research that has been made through oral histories, through the historical written histories that we’ve spoken about previously, and about our own modern-day perceptions of what longhouses were like before (European) contact.

(What we see here is a splash screen and the project was actually developed in conjunction with the town of Whitchurch-Stouffville and the Huron-Wendat Nation)

The Huron (Wendat) was a community that lived in an area of the Eastern Woodlands which now includes the Whitchurch-Stouffville township. Unfortunately, the Nation Huronne-Wendat community relocated to Northern Quebec during the time of colonization by the British and the American peoples, so there is a history of displacement and of loss with their original lands. Today they are a vibrant community that is deeply tied to the traditions of their ancestors.

So we’re dealing with a particular area that the Descendant Community actually has little current physical connections to the land but has a lot of spiritual connections to it. This is really really important for us to understand that they’re displaced people. They had to move to a completely different environment, to a different Province, in order to survive.

So we’re dealing with a particular area that the Descendant Community actually has little current physical connections to the land but has a lot of spiritual connections to it. This is really really important for us to understand that they’re displaced people. They had to move to a completely different environment, to a different Province, in order to survive.

The Whitchurch-Stouffville landscape continues to be the traditional lands of the Huron (Wendat). As such, our splash screen acknowledges this community perspective and acknowledges that numerous people worked to develop this virtual representation of the longhouse. In reverence to the community, all efforts were used to ensure the Huron-Wendat language or French was used and then English.

We really struggled with trying to figure out how we get into this experience in the first place and our community leaders suggested that you enter a longhouse by first asking people to come in. So as the button (atson) that appears on the splash screen is a request to ask to come in. It is basically “going (in) here” and that was our way of inviting people to join us on this virtual experience.

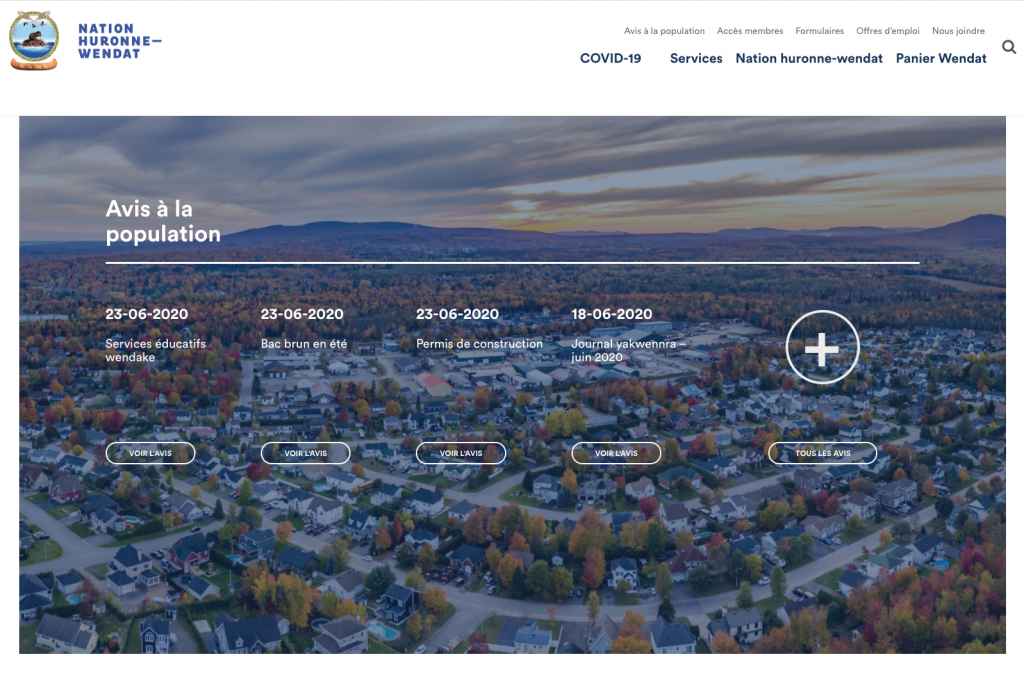

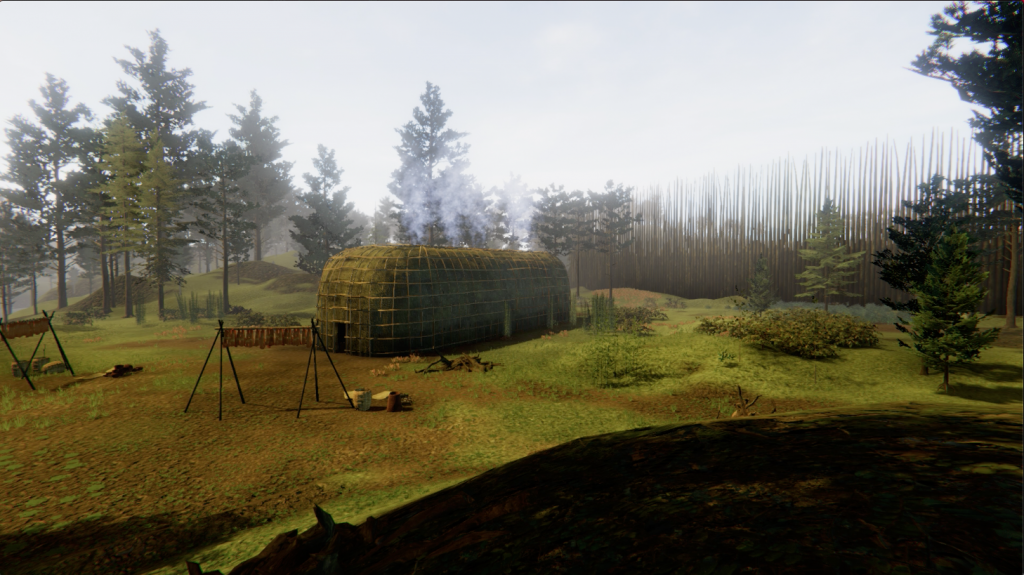

(So I’m just going to click and go into the environment and there’s a set up seeing here and we’re somewhat looking over the viewshed.)

In archaeological terms, a viewshed is a prime piece of real estate and that is where ancient peoples whether Indigenous or ancient Europeans or Middle Eastern people would live. From these people’s perspective, they knew the land very well. They were connected to the land. They understood the land and in this particular case this longhouse occupying the space that is rich in agricultural space, rich in raw materials to build longhouses, as well as to build the palisade that you see in the background, and it’s close to a water source, and that’s very important. Not only for transportation purposes (the water) but for their entrepreneurial approach to trade, not only amongst their own communities but a broader trade across all of North America. So the current view source perspective is that the longhouse in our virtual space occupies a prime piece of real estate.

Now, what you will also notice is that there’s a palisade in the background and the palisade is made up of a defensive barrier. This is actually outside of the palisade. An external longhouse’s key functions were to offer an area for guests to be invited to stay. Longhouse settlements were tight-knit groups, so if you weren’t necessarily part of a matriarch’s lineage, there was a little bit of hesitation to allow you to directly into the village itself until such time that you were deemed welcomed into the community.

This (virtual) longhouse, in particular, had two kinds of functions; it’s a guest environment and the other one is that it’s a working environment of which fishing and hunting would have occurred during the summer months. Sometimes they would have hunting lodges just slightly outside the village in order to facilitate closer access to the water sources and to the hunting grounds.

I mentioned previously in our other interview that the Jesuit Relations were a series of writings that were written by Black Robe Jesuit priests from France. They were part of the first group of colonizers that would come over from Europe into Indigenous North America. Their ill-conceived eurocentric role was to try to convert the Indigenous peoples, whether they liked it or not, to Christianity and the Jesuit writings were really a memo to their bosses back in France. Essentially they were saying: Hey, look at me. I’m doing a great job here. I’m converting all these people whether they like it or not or whether they wanted to be converted or not. And you know, send more money, send more people, please after I’m finished my job (here), give me a good position back in France.

So the Jesuit Relations (writings and personal attitudes) were filled with these sorts of glorifying and self-glorifying accounts of their adventures within Native North America, but in reality they weren’t very much welcomed by the Indigenous communities for obvious reasons. They were strange and all the people (Black Robes) had very strange customs. If they were invited to stay within the village, they actually stayed outside in these guest longhouses that you see here. However, from their perspective, these were in their minds the longhouse(s) that represented how everyone lived.

So these guess longhouses, especially the ones that the Jesuit Priests were staying in, would tend to be dilapidated or leaky or be infested with rodents and so forth and that was because they were uninhabited, and no one was staying there on a regular basis. The Jesuits would tell the story about these longhouses as being creaky, dilapidated places that were horrible to live in. But in reality, what they were doing was living in an old shed in the back of the backyard of the longhouse community and they (the Jesuits) didn’t have access to the grander, more sophisticated spaces that the local community were living in.

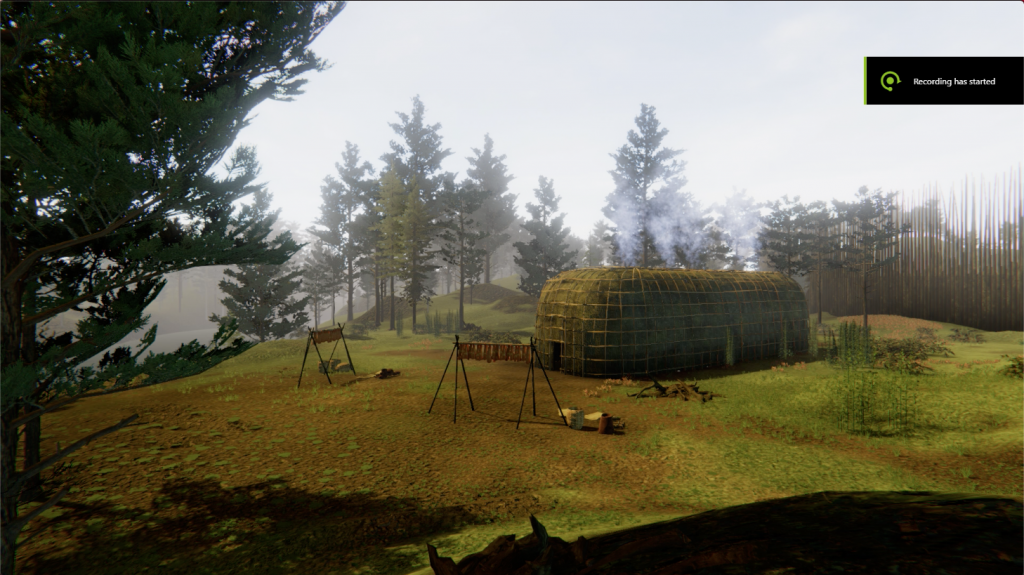

So as we move in you see in the longhouse where there’s smoke coming out of the smokestacks, there are effectively holes that are cut from the top of the longhouse. We’re walking through and seeing meat that is hung from drying racks, and that means would be both fish and venison as well as other types of meats, animals smaller game and so forth. The look and feel we’re trying to give for this virtual experience was really to be sometime in the midsummer getting close to stocking up on the winter provisions. And so forth.

The longhouses were traditionally long in the sense that they could range from 18 meters to 72 metres, which was massive. Massive amount of family families that can live in them and as we’re walking through you can hear that we’ve added sounds of people playing and dogs barking. With these sounds, that’s more to give the space more life.

And I’m just going to stop here as we entered into the vestibule or the front entrance. We’ve purposely not included any virtual characters within this representation and that’s because quite frankly, all of the people working on the virtual production team in this particular project were not Indigenous peoples. As we aren’t part of the community, it wasn’t our place to be able to visualize the ancient people who lived in these longhouses. We wouldn’t speculate what a pre-contact person would look like from a 3D character perspective and must engage and consult the Wendat community in the future in order to add virtual representations of people.

So what we’re getting is a sense of a longhouse that’s empty which is completely different than what their real longhouse would have been. A longhouse would have had anywhere from six to sixty family units in the family sleeping/quarter areas. Generally, these family units would be a mother and the husband would have been from outside of the community because men were invited into villages and into Matriarchal longhouses based on the skills and their ability to provide for the community. They would have their children there, there would also be grandchildren and there would be multiple brothers and sisters who would be potentially living in what the Jesuits had described as condos or apartments within the longhouse themselves.

A typical Eastern Woodlands (Ontario/Quebec) longhouse was anywhere from about seven meters to 7 and 1/2 meters wide. We know this quantitative data from the archaeological record, and those longhouses would expand and contract based on how many people lived in it at that particular time.

So as the Matriarchial extended family grew bigger they would take off the vestibule which is the front end of the longhouse, (the piece that we’re looking at right now) and they would take that off and then they would extend the longhouse to make it larger to create more apartments for the new family members. We know that longhouses were generally wide as it was tall, which comes from oral histories from both the Jesuit visitors as well as from the Indigenous communities oral histories. We know there is evidence that multiple types of expansions were used in order to create separate apartments.

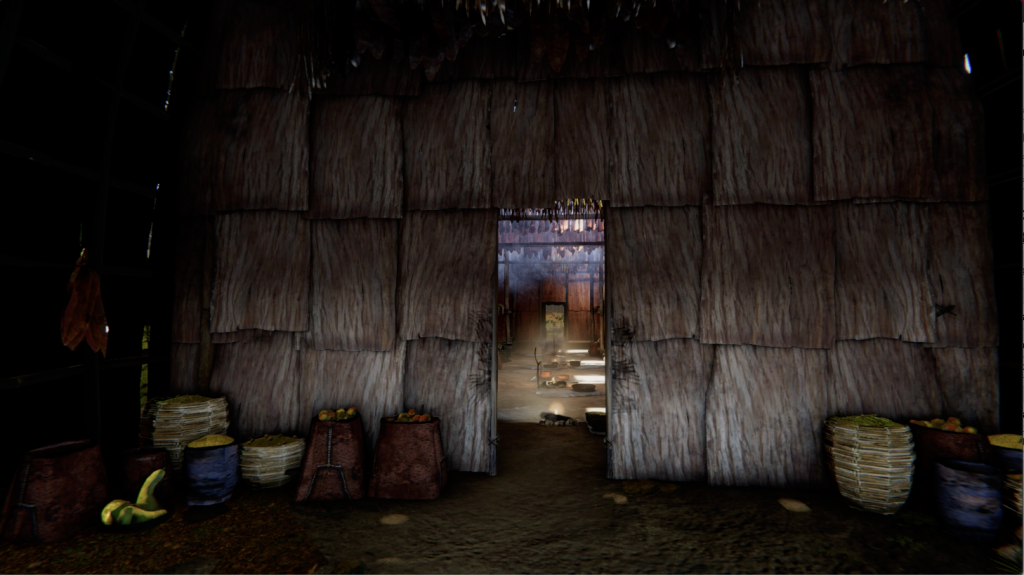

So now we’re in the vestibule and have represented the storage area quite sparsely. It’s important to note that when we’re dealing with our (Indigenous) communities/partners, that when they first engaged with this space, what they’re saying is “wait a second. There’s not enough food here. We’ve got families to feed.” This is where the harvest was stored. We had to curate a little bit of what we think would have been used. So there are apples that are inside leather or bark baskets. There are other types of bark baskets, containers that would be to hold grains and other vegetables, herbs or staples, or the three sisters; squash, maize and beans.

And hanging in the rafters above (in the picture about the rafters are filled, but the light dim as there are no smoke holes in the vestibules themselves), there would be meat so that would be hanging that had been cured already because obviously there’s no fire that’s occurring in the vestibule. A vestibule is really an entry place for people to walk into so the meat would have had to have already been cured because fresh meat was cured with smoke. So if one is going to smoke meat, you need to be in the main section of the longhouse itself.

On the door, you’ll notice it has a lot of handprints and this was an added interpretation that we had as archaeologists that people would be walking into the longhouse on a regular basis and as they’re walking in they are touching the side of the frame of the doorway. So it’s a little bit of a detail that allows us to indicate that there is human occupation here. In the doorways, they generally had during the fall and winter months, a skin or a bark covering to act as a door, that would keep the weather and bugs out as best as they could. Unfortunately for this particular project, we actually made the doorway high.

At the time, our typical height for an individual Indigenous person and French person actually in the early contact pre-contact was about five foot eight. So we’ve made the doorways that big just to allow for the virtual first-person experience to be okay for maneuverability. But in a traditional sense, the front opening of the longhouses would have been much shorter forcing people to bow and bend down as they walk into the longhouse themselves. This was a defensive technique to ensure that if they are coming into the longhouse and you’re weren’t welcomed, the people inside the vestibule protecting the longhouse had an opportunity to render the individual incapacitated or capture the individual before they wreaked havoc within the longhouse itself.

Now, you’re starting to see fire pits. There are several different types of (fire) hearths that were used; one for heating and one for cooking for each family unit. We have added the sound of people coughing and as you look up into the rafters, you’ll notice that there’s a smoke layer that is caught in the rafters, which is based on the Jesuit writings.

The Jesuits describe the roof of the interior of the longhouses being arbour-like or rounded like and at the top of the longhouse would be holes that would allow for the smoke to escape but there would still be a substantive feature about the longhouse itself and that would help cure the meat as well as cause problems medical problems for the people who live there.

I’VE STOPPED HERE

There was a study that was done in the 1970s when a group of archaeologists decided to occupy one of the longhouses that long lock just west of London and during a snowstorm, a major snowstorm and they loaded the put lots of firewood in they closed up the Longhouse but made the smoke hole slits open.

And then (the archeologists) started up the fires and realized almost immediately that they couldn’t breathe. And so they rushed outside. They came back that they played with how different types of woods would create different types of smoke and so forth. What they came up with or what they realized, was that the smoke layer no matter what they did always stayed at the four-foot level.

And remember I told you that people are generally the average height of most men in almost all Indigenous men. in the Eastern Woodlands area in Ontario or what we call Ontario today was about five foot eight.

So if you’re standing your head is actually a foot, or bit or more than two feet above the smoke layer. So you’re constantly breathing in the smoke of all the fireplaces going in the longhouse. And if you had a longer longhouse you’d have more fireplaces. So what we’ve what we’ve discovered through the archaeological record is that age 35 or 40 was generally the life expectancy of most men and women who lived in longhouses and this and if you look at the their skulls or their rib cages when they’ve been with they’ve been found in terms of archaeological excavation.

We realize that there’s a lot of cancer and a lot of smoke inhalation problems. We want to represent within this virtual longhouse, the fact that there was a lot of smoke and so the sound of people coughing really demonstrates that. That we would never be able to get away from the smoke.

The Longhouse itself would have a series of vestibules or compartments again. I’m visualizing what I believe is an interpretation of the archaeological record in the oral language.

And what I think is really important here as we sort of stare down the long version of longhouses that this is just my interpretation. push it the use of 3D technology allows us to provide a template of assets such as how the longhouses are built and whether or not we can make them seven meters wide or seven half meters wide if we can make them taller or longer if we add more fireplaces to them all of these elements within a 3D procedural environment allows each individual who Is connected to Longhouse living whether it be the descendant communities or the archaeologists or the school kids coming in to learn about indigenous history. Each person will have their own sort of interpretation of their own visualization of what longhouses look like and this technology allows us to do that.

So what you’re seeing here is my interpretation of the bat and there’ one of those interpretations was that there were birch bark panels that separated the community or the family units into condos apartments that that’s I’m taking this information from other archaeological sources and some other oral histories, but there are opposite histories that say that there were no covering. So it was completely open to everybody and it was one large communal environment. So again, again, what we’re seeing is a personalized interpretation that should not be misconstrued as being accurate in any way whatsoever. So I’m just really visualizing the information that you’re seeing. This information could be everything from birch bark pods to the types of foods that would have been stored in the space to the types of bark that was used for shingling and so forth. Or even for the benches and so forth now, we’re moving back outside and we’re starting to hear this on kids again and shortly.

We’ll hear some cicadas chirping birds and hopefully there will be some dogs. And we’re walking down into the view shed and see the beautiful spot to the river and the river again was the lifeblood of Indigenous communities both for the fact that they created their village there. The river provided water, provided food and it also provided entrepreneurial transportation to other indigenous communities.

So the Longhouse the virtual longhouse is really a combination of multiple elements. One is to appreciate the communal environment that are Indigenous descendants had both before contact and after contact and as we’ve discovered from an archaeological perspective longhouses actually changed after they changed architectural approaches after contact to be more European-centric which we have.

Now, I haven’t personally done any research to find out whether or not there was any whether that approach was better than a different approach. But from a pre-contact perspective longhouses were different from all sorts of different communities. So if you live south of the Great Lakes you are longhouses were a lot thinner and and longer if you lived further west your long houses tend to be a little bit more beefier.

If you live far to the east your longhouses would use a different type of wood. That wouldn’t have been available in these environments. So the thing that I really love about longhouses is the fact that it meant the same thing to almost every community whether it’s they were Indigenous here in North America or in Indigenous communities across the globe. It was a meeting place for everybody come together and live together, but from an architectural perspective, they they ranged and they were buried in there were unique in their own respective nature and that gave a real appreciation for the fact that there is a broad and vast creative spirit that was in all of these Indigenous communities building these impressive environments.

Michael Mihalicz: So I received some of the teachings from the Mohawk Elder out. He mentioned that people coming to the Village weren’t necessarily allowed into the village right away. Typically, they would set up camp outside the village until they were welcomed into the Village. Then in wartime, men coming back from the battlefield weren’t invited back into the community right away, you know the battle weary and and they didn’t want to introduce that energy into the community and so they would reside just outside.

Michael Carter: I hadn’t realized the Warriors, that the warriors would have stayed as they came back. That makes complete sense. The palisades were there. They were to keep the riff raff out if you like if you were a Jesuit priest. It makes total sense that these these longhouses wouldn’t have

internal to the community and we’ve recognized that they tend to be less than 18 meters in length, which tells me that a smaller group of individuals occupying the space for a shorter period of time.

I’ve never come across any historical writings on that but now you’ve got me interested. So I’m going to have to have to take that up right? I think there are a lot of teachings in building the longhouse that you don’t necessarily get from seeing the completed product.

Michael Mihalicz: Building a longhouse was a community effort, you know, and everybody coming together, men as old as you know, 50, 60 years old or pitching in wherever they could. You know harvesting the trees and when I talked to you about this previously, but how we didn’t clear all the trees around where we were going to build the Longhouse. So we wanted to do it in a very sustainable way. And so we took trees from deep in the woods, you know, where the ecosystem would recover and so it made for a lot of work. Getting huge trees back all by hand hundreds of meters back to be placed and just we used traditional tools as much as possible.

So it wasn’t it wasn’t an easy project. So we also made an induction cook and a totem pole and a teepee all traditional pre-contact and it was none of them were easy, you know. The role of community and sort of everybody pitching in and that a lot of the ways that things were done weren’t necessarily the most effective in achieving the objective which in this case would be to build the Longhouse but they do serve a deeper purpose and strengthening bonds in the community and ensuring that that what you’re doing is in harmony with the land that’s that’s sustaining life in your community.

Michael Carter: Wow, so, you know, I’m not sure if you know this or not or if you’ve heard these these figures but the this virtual representation is of the Jon Batiste site in the Whitchurch-Stouffville area and that particular site was excavated a few years ago when they were putting in new subdivision and as they started Excavating they realize that they didn’t

have a village and Indigenous pre-contact Huron, or one village, they actually had a city. They excavated over a hundred longhouses in various sizes and formats and a massive large calibrated city barrier, but they also the interesting thing from this particular ocular archaeological apartment was that the long houses that were built by different communities that we’re coming into the safety of the city itself.

They had a waste removal system, they had a fire brigade. You had long trenches and those trenches were for waste waste products and so forth. So we knew that there was a community garbage program, you know, a garbage collection program and we also based that understanding on the oral histories. We knew that there was a fire brigade, because obviously you’re living in a community full of wood. So fire was always a primary thing, but to sort of get back to the notion of being sustainable and the acquisition of proper wood and so forth for these longhouses.

In the city, you’ve got a lot a hundred longhouses. I think it was estimated that you had actually had to cultivate 70 acre or 70 hectares of land just to acquire enough wood to build the city itself and then to feed the city after it’s been de-stumped, and so forth and made into an agricultural zone.

Michael Mihalicz: The sustainability aspect goes beyond just the sourcing of materials and really gets into creating a more cohesive community, you know one and that really comes with just the way that things were being done because community is everything. That was I believe, you know, their main means of survival was having a strong tight-knit like you said community of people and so a lot of the methods that were used. I think we’re designed very intentionally to strengthen ties within the community.