Around the Medicine Wheel

Tiondiah! (Let’s all make it!)

An Archaeologists Dilemma (Michael’s Journey)

As longhouses were entirely made out of wood, unlike the stone-built heritage of Europe, Greece or Egypt, what remains architecturally of these once vibrant longhouse communities are the posthole stains in the earth, just below the soil line, where the foundations of these massive structures once stood. When a new archaeological discovery of a longhouse community is made, only the outlines of the longhouses and the material culture buried within remain. As such, archaeologists use plastic straws to indicate where the longhouse posts would have been driven into the ground, which would then support the outer walls and bark singling. By excavating these posthole stains, we know the types of wood being used, the diameters of the posts, how many posts that were used as well as the width and the length.

Our “mental image” of a typical Iroquoian or Iroquois longhouse seems to have developed from very little cultural-historical, visual, oral or written material. The Jesuit Relations along with very limited historical images but augmented with a strong Indigenous oral history and has given us what we “think” a longhouse might have looked and felt like. Interviews with archaeological and heritage practitioners also revealed consistency in how modern interpretations of the visual, cultural and environmental aspects of longhouse use continue to be static. Whether the mental image is correct or not, most agree that they can be a long “half cigar-shaped” multi-family residential, ceremonial or public administration buildings made of a wood pole framing structure and shingled with bark.

What we “Think” we Know?

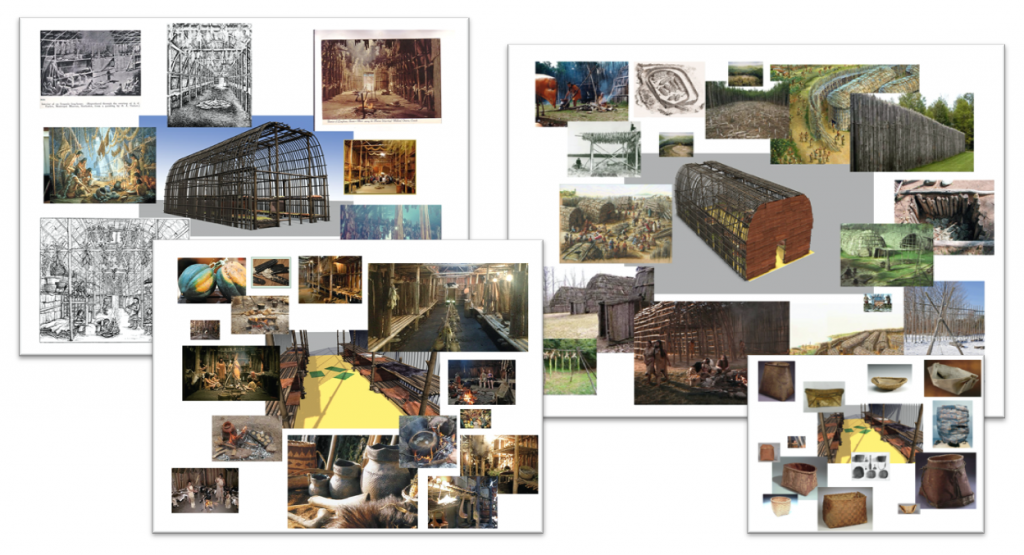

The archaeological, historical or oral histories only give us a slight image of what the longhouses would have looked like from the ground up. Some historical writings or representations such as the one above clearly demonstrates the colonial-eurocentric language and attitudes of the non-Indigenous people. That is where a virtual construction of the known archaeological information, combined with descendant traditional and current longhouse building techniques help to (re)imagine what these architectural wonders looked and felt like.

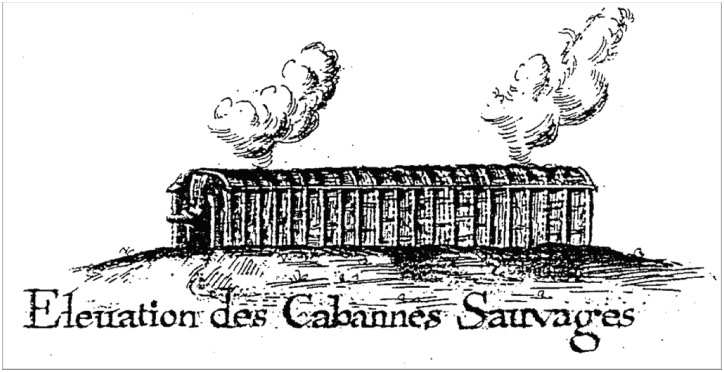

There are multiple variations on the visual representation of longhouse framing techniques, but Dean Snow (A), Mima Kapches (B) and JV Wright (C) paint three varying cultural-historical interpretations of longhouse style which seem to be the most commonly referenced when discussing longhouse look and feel. Each has its own distinct stylistic qualities but all variations can be interchangeable and are derived from the same archaeological site post hole stains.

However, it is important to keep in mind that the archaeological record itself, does not reveal any real visual guidance above the soil line and thus we as archaeologists are reflexively building visual meaning whether in the field or during post-excavation analysis.

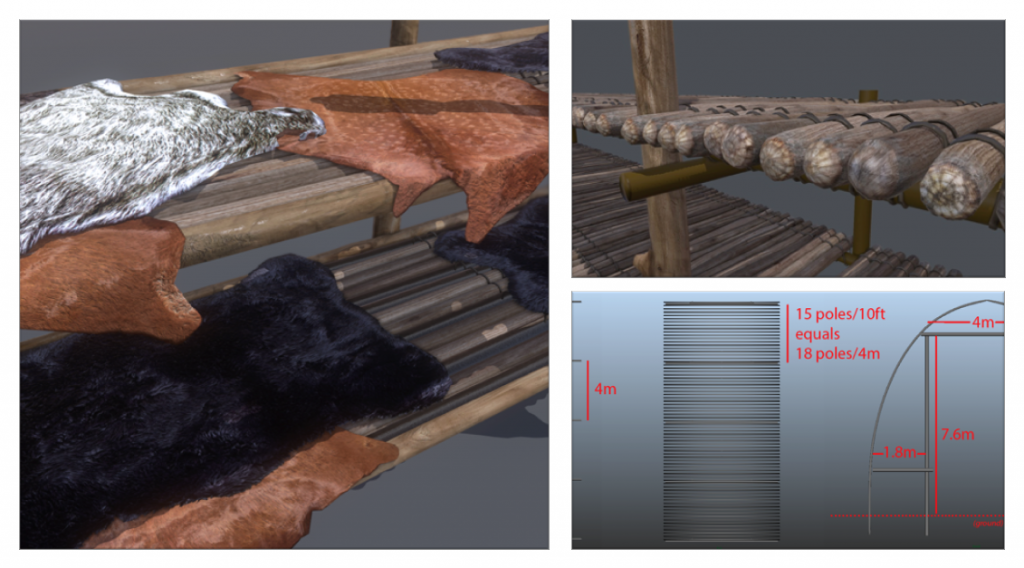

Ontario Archaeologist Christine Dodd examined the archaeological excavation data of over 400 longhouses, collating the basic building dimensions of a 16th-century Eastern Woodlands longhouse:

- An average of 18m’s in length.

- Height is as tall as the width (note that the archaeological record only provides data on the width and oral history provides data on height). Generally, the average width is 7.6m’s.

- The centre corridor width is 4.0m’s.

- Sleeping platforms/family cubicles were generally 1.1-1.8m’s in width, 3.7-4m’s in length and 1.8-2m’s in height.

- The actual sleeping platform itself has been recorded to be anywhere from 0.30-1m off the ground level with the roof of the platform where personal storage was commonly thought to be, being 2m’s from ground level.

- The average interior support post was 8-15cm’s in diameter.

- Exterior wall post diameter was 1-3cm’s in diameter and on average there were 4.5 poles per meter along the length of the longhouse.

- Typical fire hearth spacing was 2.9-3.6m’s between hearths. Each hearth support two families on either side of the longhouse.

- Exterior roof and wall shingles were 1x2m cedar or elm shingles.

The difficulty is that most academic literature describes longhouses in a similar fashion, leaving the reader to visually imagine what a longhouse might look like. So our conundrum is, how do these measurements equate visually if they were to be represented?

In addition to the basic measurements that Dodd was able to collate through the archaeological site data, there is a discussion between the roofing structure, which is highly dependent on the initial support post or internal skeletal structure of the longhouse. Currently, as discussed above, there are three major internal structural forms or supports that make up the external visual differences in longhouse construction as described in historical accounts that have been theoretically suggested (Snow, 1997; Williamson, 2004):

- Wright’s reconstruction of a longhouse at Nodwell suggests a π shaped internal support infrastructure existed which would have supported a visual ratio of 4:1 in height between the main building and a separate arbour roof (1971, 1995);

- Based on extensive historical European oral accounts and two specific visual representations of Seneca longhouse floor plans from the 1700’s, Snow suggests that longhouses might have had a 60/40 split between longhouse body and a separate upper roof (1997);

- Kapches, using Iroquoian oral history, suggested that the longhouse walls and roof might have been entirely integrated by long exterior posts lashed at the center roofline forming a continuous arbour effect (1994).

In addition to these three “theoretical” assumptions on the building shapes, there are a plethora of unique building styles and techniques presumably employed prior to contact and most definitely used post-contact by every local and regional Indigenous Eastern Woodlands Nation. So variability and thus building assumptions would be wide-ranging. Thus goal of virtually reconstructing a proto-typical Eastern Woodlands longhouse is to provide a platform for stakeholders to discuss, while at the same time digitally change or add to the narrative.

The Unkown

The notion of visual accuracy is a theoretical discussion. There is no way to accurately reconstruct an Iroquoian longhouse from the 16th century. As discussed there were no significant visual representations of longhouses from the 16th century and Oral/Written histories were questionable. We had to “reimagine” what the longhouse might look and feel like purely from the available material. By relying heavily on Dodd’s quantitative work and recent longhouse excavation data from the Wendat Mantle Site North of Toronto, it was decided to build a prototypical Iroquoian longhouse as opposed to creating a specific longhouse directly from the archaeological site data.

Everything from how poles would have been cut, to the cordage used for lashing, to whether bark was harvested or left on the poles used for framing was reviewed and tested within the 3D modelling process for the look and feel. External Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural-historical specialists provided guidance, however, the key element was that we were visualizing the longhouse based entirely on personal perceptions and interpretations of the archaeological data.

We freely chose a pragmatic eclecticism to determine which cultural-historical element or perspective we would use to envision our visual mental map of a longhouse. As such, the “making”; the construction of knowledge through the synergies of skill, tools and context, began to reveal a profound theoretical grounding for meaning-making within virtual environments (Ingold 2011).

As we constructed the longhouse, it was a negotiated process between what we wanted to visualize and what the software, our skill and the final delivery platform would allow. Using Autodesk Maya, an industry-standard animation and VFX software application, alongside traditional lighting and rendering techniques, the test images became photorealistic, which posed problems around the notion of authenticity and authority later in the process.

We also found that we were challenged with probably some of the same building techniques and decisions Iroquoian builders might have encountered during the process of their own physical longhouse construction. The material used would have had its own materiality and thus construction methods and techniques would have been dictated by that materiality. So the virtual building process informed our construction of archaeological knowledge.

We also used the head-mounted immersive VR technology to do virtual site inspections of the build during and after construction. This allowed for almost real-time course corrections if there were modelling assets missing or if we needed to make changes due to construction problems. It was a unique and surprising method of constructing archaeological thought.

Using a traditional film research technique for scene/set development called “mood boards”, we collated imagery that was both archaeologically/historically representative as well as modern visual interpretations of longhouse construction and use. We appropriated visual references when needed but tried to follow a pragmatic approach to how a longhouse would have looked and felt like. These sources were both Indigenous and non-Indigenous yet provided a commonality in visual referencing, however through a modern lens.

The most difficult task was the acceptance of the visual style as it was migrated from the Autodesk Maya building environment into the Unreal Game Engine, which called into question the “authenticity” of the overall experience. As we migrated the models into the real-time engine, assets such as textures, environments and the models themselves had to be significantly reduced in computational size to allow the real-time engine to perform effectively.

This gave the imagery a game-like look, unlike the photo-real renderings from the previous Maya related tests. Does photorealism make the experience more “authentic” or is it the ability to actually interact with a reconstructed archaeological landscape that makes it “authentic”? Or could there ever be authenticity when visualizing constructed knowledge?

To enhance the reimagined environment, reconstructions of 16th-century Iroquoian artifacts from the Lawson Site were placed within the longhouse to test perceptions and placement throughout the daily lives of the inhabitants.

The final result was the ability to allow community stakeholders, archaeologists and the general public to navigate our reimagined constructed world in real-time while still getting a sense of how they themselves could be reflexive of their own cultural-historical perspectives.

The visual narrative we were building upon was a sole longhouse outside of the main palisaded village close to the river. This afforded us the ability to keep the model count low in order to increase the speed and quality of the interactive render.

Interactive enivronmetrics such a light, smoke, dust and wind were added. Dirt, fingerprints, creosote, soot, ash and other assumed markers of human existence were carefully placed throughout the longhouse to add to the authenticity of the phenomenological experience.

Props were added to give a sense of tools, objects and artifacts that would have been representative of the particular time and place. Some elements were completely left out such as skins for the doorways or the bark shingle flaps for the smoke holes on the roofline either due to difficulty in representing those elements in real-time, or just the lack of available computing power. Thus considerable internal negotiations occurred based on the constraints of known cultural-historical material and available technology.

We purposely didn’t add any avatars or animated characters into the virtual space for obvious reasons around the representations of the “other” and see this as the next step in participatory knowledge building with descendent stakeholders in the future.

Ultimately, the failures of the visualization directly capture the failures of the archaeological knowing. What we don’t know we must speculate until a community member can enhance our knowledge through their vision.