About the Authors

Ewan Cassidy

I am a first year undergraduate student in the Environment and Urban Sustainability program at Ryerson University. Throughout my youth I’ve found further and further interest in the effects institutions and systematic structures have had upon the mindset and mental health of those in my generation. I’ve known Dr. Carter since I was young and am proud to call his son one of my closest long-time friends. Dr. Carter asked me to join him, Tanya Pobuda, and Michael Mihalicz as an Indigenous research assistant and to bring my perspective to the project.

As a follower of the Jungian approach to my own mind, I’ve spent time on how I can integrate my practice of introspection into all aspects of my life. Born in Toronto at Mount Sinai Hospital to a newly emigrated mother, and an Indigenous father, I’ve grown up with quite different cultural influences.

With my parents separation when I was young, learning the traditional teachings of the Anishinaabe culture and several others with my father, I’ve learned to integrate multiple cultures and to respect the tradition and teachings I receive. Speaking Japanese with my mother and growing up as close to the classic Japanese home that you can get with a 14-hour flight away not only made my resume better with “bilingual”, but taught me to open my ears and mind to different social laws from across the world.

From a young age my father and I would participate in long remembered traditions; from sweat lodges, sitting in ayahuasca ceremonies, sitting up all night in the teepee in a peyote ceremony, and even learning the Taoist teachings and Reiki Healing.

“Ayahuasca Inspired Art – August 2012” by Howard G Charing is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

“Ayahuasca Inspired Art – August 2012” by Howard G Charing is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Growing up in an upper-middle class neighbourhood in Toronto with a racially and culturally diverse population, I found myself surrounded by people with contrasting ideologies and ways of thinking to my own. Within this economically privileged area, I found myself in an unstable household, developing a sensitivity to my emotions.

This sensitivity led me to deal with a multitude of mental health issues throughout my teenage years. In the beginning, I had martial arts as a channel to direct these emotions and stressors; at 15 I quit martial arts altogether, unwilling to deal with the unhealthy culture one can find in many martial arts practices. In my senior year of high school, dealing with substance abuse, I was diagnosed with major depressive episodes. Spending time in mental health wards, and couchsurfing. In these times, the spirituality of my life that I grew up with were no longer present in my life.

At 18, my father put me through a Bwiti psychospiritual journey, and my eyes were opened. The clouds of thoughts and feelings surrounding me had dispersed and I could see clear as day, thus beginning my journey of introspection and deeper understanding of not only myself but the ocean of life in which I navigate.

“In the Jungle with my brothers” By Jimmy

“In the Jungle with my brothers” By Jimmy

A year after the ceremony I transfered to the Native Learning Centre (NLC), an Indigenous high school in Toronto. While attending the school I began training under my father and learning the Bwiti teachings of life. At the NLC I met Indigenous people my age, who were not as privileged as I was growing up sheltered from the systematic oppressions of First Nations on Turtle Island. The cloud that once covered my eyes surrounded my peers.

I do not claim to know what it is like to live on reservation land, what it is like to have a parent who lived through residential schools or the Sixties Scoop. My grandmother was fortunate enough to escape that, hiding her Indigenous identity until long after she passed away.

I do know that the epigenetic trauma that Indigenous people experience is all too real. While I feel like a fraud at times, and even have questioned my Native identity in the past. I know that the healing and reconciliation of my fellow Indigenous peoples is part of my purpose in life.

It is with this introspection, and desire to heal people that I joined this project. I have received this gift to work on this project keeping in mind that this project is not for me, Dr. Carter, Tanya, Michael or anybody else involved; This project is, through and through, for the reconciliation of traditional teaching, and the healing on the land.

Tanya Pobuda

I am a PhD candidate in the Communication and Culture program held jointly by Ryerson and York Universities. I’ve been studying the use of virtual reality (VR) in pedagogy for the past three years. I was looking specifically at the use of VR in training students and business professionals to feel empathy for others in small team settings. I met Dr. Michael Carter in 2018 when I was supporting a class on private-, public-partnerships to solve real-world business problems for Ontario organizations. I learned of his research and read his dissertation, and I was intrigued about his process and methodology for recreating immersive worlds. His work on recreating a 16th century longhouse, his reflexive exploration of his assumptions, the conflicting reports of life in a sprawling, diverse metropolis just outside of what is now London, Ontario. I wondered, how might the longhouse be experienced by secondary and postsecondary students?

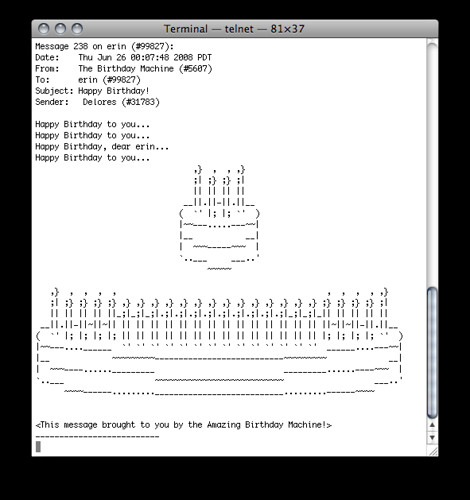

I am believer in the sensory magic of VR. I have been transported to weird, disorienting worlds in virtual space since the early 1990s. I dabbled in text-based worlds in Xerox Parc’s LambdaMOO, and programmed objects and rooms designed to interact with other visitors. I chatted with a penguin from Taiwan in Worlds Chat, a 3-D immersive world and gigantic chat room that was globally popular in the early days of the Internet. I’ve created immersive worlds and 3-D objects by hand in VR hackathons held by Dames Making Games.

Here’s a slice of an immersive world circa 1994.

Lambdamoo” by everyplace is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

I was thrilled to be a part of this project. This project had an importance, a gravity and a feeling of such critical importance that I was mostly feeling just one thing: nervous.

I’ll explain.

I am a white Settler. I am a researcher of Irish-Czech descent. My last name is a crude insult in Czech, meaning hobo but “worse” according to a Czech-speaking man I met one day several years ago. He told me not to “tell anybody.” In reality, I literally can’t stop telling people that. Czech speakers always titter when I introduce myself.

I am cis gender. I live in one of the biggest cities in North America. I’ve had a reasonable career, starting as a reporter, working as a marketer, communication professional and certified project manager in tech and life sciences. I recognize that I occupy a privileged position in my society. I (rightly) feel guilt and shame for how we, as white Settlers, have treated Indigenous people: First Nations, Métis, Inuit and Innu. We were visitors to this land. I realized, shortly after coming to Ontario, I got to see the ugly face of racism in Canada up close during my upbringing in Canada’s North.

I spent most of my formative upbringing in a rural community just outside of Peace River, Alberta. We lived on a farm in what was called Judah, but when the grain elevator burned down by the railroad tracks, and then someone shot down the road sign, Judah not longer merited even hamlet status. The only proof of Judah’s existence lay rusting in the dirt ditch beside the gravel road to my farmhouse while I was still in elementary school.

“IMG_0054” by stingp is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“IMG_0054” by stingp is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

If you look at the aerial, satellite view of my family’s home, you can see the landscape is raked and scarred by farming operations, and pock-marked by the clear-cutting of the traditional poplar forests. When we transformed our hobby farm into a full-blown agricultural operation, we grew cash crops of wheat and barley to start. I found black slate arrowheads buried deep in the furrows made by our plow in our barley field near the Smokey River. My family went on to create a cow-calf operation, and bought a Caterpillar tractor to knock down the trees to make room for grazing land for the cattle. I dug tree roots out of the ground to ensure that cattle didn’t break their legs on what was left of the trees, their ragged, charred roots (I hated that job). As with cow-calf operations, we kept the female cows, and sold the yearling (or less) steers to feed lots.

My family lived much of our time in the erstwhile Judah living in a back-to-the-land style. We grew our food, for the most part, we hunted in the fall. If we bagged a moose during hunting season, that meant red meat for the winter and spring. Of course, this was merely *most* of the moose carcass, less whatever the dodgy, and I often thought, illegal butcher located in a broken-down trailer home skimmed off the top. For us, beef was for money, moose was for food. We lived surrounded by coyotes, deer, moose and the odd black bear, one of which killed our toy dachshund dog.

I lived throughout most of my childhood on Treaty 8 territory. This was an agreement made by Queen Victoria and the First Nations of the Lesser Slave Lake area. The treaty was struck on the ground that was just south of Grouard, Alberta.

The Treaty 8 land acknowledgement reads accordingly: “we honour and acknowledge all of the First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples who have lived, traveled and gathered on these lands for thousands of years.” Signs of that past life were all around me, buried arrowheads from the warfare near the Peace and Smokey Rivers in the soil, plaques about the peace between warring nations on the banks of the mighty Peace River. I grew up hearing Y-Dialect Cree being spoken on the streets of my town.

I watched my First Nation classmates being bullied, harassed and intimidated by white students and teachers alike. I was bullied right along with my friends. I was an outsider kid, the kid who came from the city, born in southern Alberta and not related to the older, established white families who ran the town. I was the kid in school wearing filthy rubber boots surrounded as we were by dirt and gravel roads. I trudged in too-big boots to school, a 45-minute trip by bus, wearing my eccentric, homemade, wood-smoke-smelling clothing from our home’s wood-burning stove, and the burning barrel where we set fire to our garbage (sustainable! ((not))).

The bullying I suffered was nothing like I saw happening to my First Nations friends, members of the Cree and Dene communities.

The systemic racism in my town would be evident to any visitor but might seem like just another part of life for those who lived there. There’s a McLuhan quote I think about frequently says: “One thing about which fish know exactly nothing is water, since they have no anti-environment which would enable them to perceive the element they live in.”[1] That quote sums it up. We couldn’t see what we were, what we continuously did. It was so entrenched that it was as habitual as waking up in the morning, seeing the sun in the sky. The inequity all around us as kids, its unrelenting frequency turned a sharp pain of outrage to dull ache of depressive resignation.

I knew I wanted to get out of my home town as soon as I could leave. I remember plastering a photocopy of the Academic Diploma criteria to the back of my particle board door in my bedroom. I was stare at it night, and I studied so much in high school I got bronchitis. I coughed into the night doing math homework. I left at 17 to travel to Ontario to attend the journalism program in Ottawa. I was warned by literally everyone in my town that Ontario was dangerous, and I’d never make it. I never made it but I didn’t go back. I carried the guilt and the shame of what I witnessed growing up and channeled it into being a reporter, then stumbled unhappily through various corporate jobs as a communications person. I returned to graduate school in 2016.

I’ve never forgotten the helpless feeling of living in my small community, knowing there was no one to tell when my friends were being hurt, getting bullied and threatened, and knowing you couldn’t go to your teacher, your principal, or your government for justice, because they were a part of the racism and injustice you could see with your eyes and feel in your chest. Indeed, officials were actively participating in the racism. Childhood, I have often thought, is all about a feeling of helplessness. Systemic racism, as my Black, Indigenous and Persons of Colour (BIPOC) friends, colleagues and leaders have shared with me, is a deeper kind of helplessness, and about having nowhere to turn for a feeling of safety, for some sense of control or any kind of peace.

It is with this understanding, and with the humility and anxiety I felt that I turned to this project. I’ve been privileged to work with and be welcomed by Indigenous researchers, and members of the Indigenous community. As a white settler, I come in the spirit of service and atonement for all the wrongs that I and my ancestors have done for generations. I can only hope to help in a small way, and provide some useful service to Indigenous people and willing learners, those committed to healing with and restitution for the Indigenous peoples.

Michael Mihalicz

Michael is a PhD student at the University of Glasgow, the Indigenous Advisor at the Ted Rogers School of Management and is an incoming faculty member in the Entrepreneurship & Strategy department at Ryerson University.

Michael strives to help people be more effective decision makers. His research combines principles from Psychology and Economics to explore how people make decisions, and what causes them to make poor choices. His research findings have led him to devote his personal and professional life to help people understand how drive states subconsciously impact decision-making and predispose them to irrational behaviour. Michael is also committed to providing underprivileged communities access to education.

In his role as Indigenous Advisor, Michael is helping to increase access to postsecondary courses for Indigenous students and is actively involved in overseeing and supporting reconciliation priorities across campus. Since 2012, he has also been working to afford student inmates across Canada access to postsecondary education and continues to break down educational barriers by finding creative solutions to institutional concerns.

Michael Carter

I have had the pleasure and opportunity to work over the last 32 years within the Animation and VFX Industry, bookending my creative industry career first as a field archaeologist and now as an archaeological researcher. My career aspirations started in the later 1970’s and early 80’s in public school, watching the first Indiana Jones movies and visiting the Royal Ontario Museum and the then newly built Museum of Ontario Archaeology in London Ontario. In high school I was greatly influenced by the Italian Renaissance; it’s artists, community and history. Following my passions of Art, Archaeology and History, I attended the University of Western Ontario for a double honours degree in Visual Arts and Archaeology in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. Upon graduation, I started my career as a field archaeologist and spent almost a year excavating a mixed and highly stratified archaeological site called “Oversite” at Hwy 7 and Yonge St. just north of Toronto in Ontario Canada. It was however my time on this site that inspired me to take a new direction into the world of computer animation which was just starting to gain publicity with movies such as Jurassic Park and Terminator 2. I continued my technical training in computer animation at Sheridan College in Oakville Ontario in Computer Graphics and then in Computer Animation. Graduating in 1996, I started what has become a long career in animation and VFX, working internationally and nationally on many children’s animated series and helping to develop some of the very tools and techniques animators today deploy in their artistic craft.

My passion however has always been in the virtual recreation of archaeological objects and landscapes. With that in mind, I returned to the University of Western Ontario and completed a PhD in Archaeology in 2017, being one of the first researchers at Western to study virtual archaeology by combining computer animation with archaeological research. My particular interest is in the virtual and physical reconstruction of pre-contact, North American Eastern Woodlands, Longhouses and this project, along with the virtual longhouse experience, tries to address through my own lens, the archaeological record, the oral histories of our Indigenous communities and the historical accounts of European peoples.

- McLuhan, Marshall, War and Peace in the Global Village ↵