6 Introduction: What is Theory?

Before taking this course, you will have had countless experiences with the term theory. It is core to any academic discipline, yet it can often be difficult to understand what the term means.

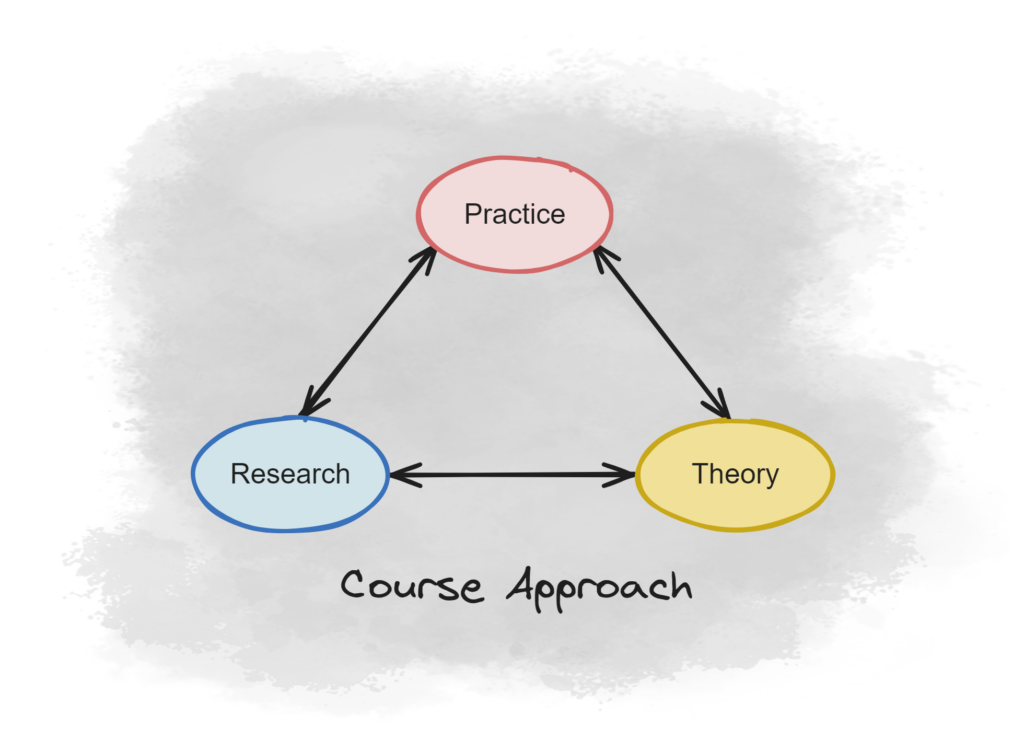

I like to begin a discussion of theory by differentiating it from what it is not. Theory is not what we do in our day-to-day lives, such as teaching approaches like Reggio Emilia or Montessori. You will recognize such pedagogical models as part of practice.

Theory is also not the numerous studies you have read that perhaps involved observing children or families, or asking them questions and generating various summaries based on qualitative or quantitative measurement. You will recognize this as research.

The following diagram illustrates the complex relationship between these three things.

Theory can be defined as a set of ideas generated to describe and explain something in the world. In this case, we are concerned with theories attempting to explain cognitive development or children’s thinking. We must begin with ideas — there is no way to avoid that. Even if we think we have an original idea, it is likely based on something bigger or that has come before. Therefore, when I think of theory, I think of many perspectives on children’s thinking over the years that have deep and often historical meaning that build upon one another over time.

Some of these theories have also been examined through research; some may say they have been “tested” through “empirical” research. Research, or studies, are typically carried out by professors all over the world. Studies involve observing children in various settings, many of which you have learned about throughout your program. This is where we discuss “peer-reviewed journals” and a sort of chain, or progression, of studies that build upon one another over time. We try to carry out studies to better understand children’s thinking, but our studies are informed by big ideas or theories. What the studies reveal about children’s behaviour, in turn, impacts theory.

What Theories Are Valued, or Even Included, in Textbooks?

So what happens when children’s behaviour is not looked at in the context of where it occurs or when only some behaviours are deemed appropriate for study? Limitations in what we observe in young children can narrow the opportunities to challenge ideas, or theory, profoundly.

In the social sciences, or indeed in the sciences, we often ask ourselves, “What constitutes data?” For some, data only emerges under strict controls that ensure one data point is comparable with another. For others, only data gathered over time from within a meaningful context can be a valid indication of what is going on.

Unfortunately, social science research data is gathered under strict sets of parameters and is limited to those who are willing to participate in studies. So, in a discipline that is already narrow in what it will ever be capable of, we must be wary of any theory that purports to know generalizable conclusions on children’s development. Therefore, the evidence we gather to enlighten our theories is, in itself, flawed. But instead of abandoning social science research altogether, it is the position of this text that more and more data from broad-ranging voices and peoples will serve to at least address this fundamental flaw of the field.

Pivoting now from data to theory, let’s consider another question: what happens when we restrict the number of “big ideas” allowed in textbooks and classrooms? You have a one-sided perspective that is not representative, and even the construct of deciding what ideas are to be presented and what are not is an instrument of colonization that favours the ideas of the culture/nations in power.

As discussed in Chapter 1, theories in cognitive development texts have exclusively represented European/Western big ideas — although some theories are more inclusive of diverse voices than others (to be discussed in detail below). This is not to say that the other ideas have been inaccessible to the world of theory and research; rather, cumbersome notions of “science” and “objectivity” have historically weighed heavily and exerted undue influence.

So, is social interaction part of science? Is it part of psychology? These are philosophical and cultural questions that scholars — both within and external to psychology — would have many differing perspectives on.

From my perspective, defining science is not of concern to childhood studies. We are ultimately interested in understanding children and families in the meaningful contexts of their lives and being able to best support their learning and development within those contexts.

While there have been no explicit criteria for what constitutes a theory in a textbook on cognitive development, perhaps the reality is worse than having such criteria; it has been implicitly Euro-centric, and moreover, that Eurocentrism has been implicitly deemed as “scientific.” European theories are one way of looking at children’s thinking, but there are many other ideas, theories, and philosophies that help us to understand different ways of thinking and learning, as well as meaningful differences in how they develop in young children.

Therefore, it is the position of this text that:

- We must think about childhoods, not about a singular childhood. The time for having a single chapter on cultural or individual differences is gone.

- In the modern post-colonial context, a multiplicity of voices and evidence must converge from different places to reflect the tremendous diversity of thought in our world — and even within Canada.

- We must not restrict our theoretical models of children’s thinking to just those taught in university classrooms or discussed in scholarly literature. Anthropology and cultural studies offer either:

- a critical perspective on adopted theories from the West with reference to their own cultural values and histories; or,

- alternate understandings that are external to the more commonly studied texts and accounts found in university classrooms (or at least in psychology-based university classrooms).

Reflection Journal

Reflection 2.1: Can you remember a time when you thought that a theory just didn’t make sense to you based on your own lived experience? Write a paragraph about how you think culture may or may not have played a role when you were trying to relate to a theory that didn’t resonate with your experience or worldview.