13 Defining Attention: Approaches in Experimental Psychology

Think back to the last time you walked down a busy city street. You may have experienced many things through your senses: perhaps the sight of a building, the sound of a baby crying, the scent of a food truck, etc. But surely you couldn’t notice everything in the environment — that would be exhausting!

As we actively process stimuli in our environment, we are inevitably selective about which things we notice or perceive. Attention, therefore, is how we focus our minds on one or some set of things while excluding others.

Western research, as presented in the two primary textbooks that I draw from for this text (Siegler and Alibali, 2019 and Gauvain, 2022), focuses on the most common senses through which we use our attention, particularly in infancy: seeing and listening (or vision and audition). Experimental psychologists have created intriguing ways to measure attention in infants before they can even talk. They have done this by studying infants’ responses to sights and sounds around them.

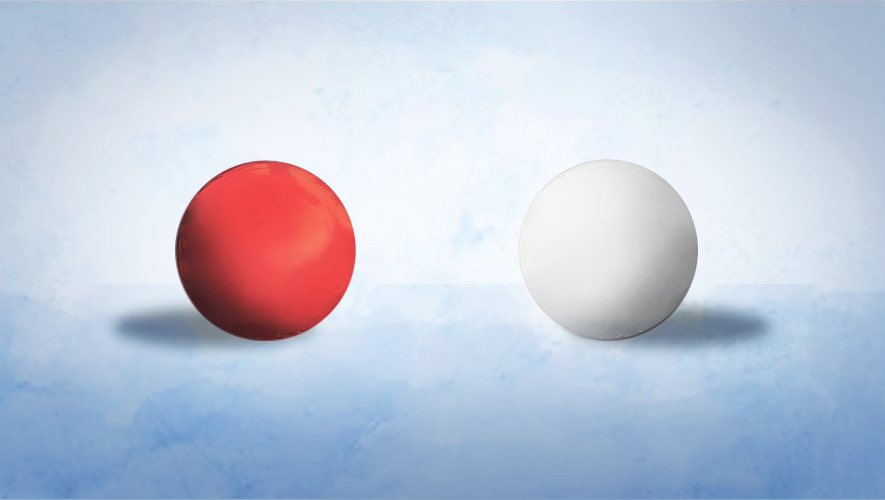

Imagine you showed an infant two different stimuli — one red ball and one white ball — and they were more interested in the red because of its bright colour. If we hold the balls next to each other, and the infant’s gaze, or even the direction their head is pointed, changes to focus on one over the other, it is pretty easy to tell they are paying attention to one instead of the other.

Experimental psychologists concluded that infants are paying attention to one (let’s say the red ball) of two stimuli if:

- Their gaze is directed toward the red ball

- They may look at both, but they look longer at the red

- They turn their head toward the red ball

Another discovery experimental psychologists made was that infants show different physiological signs when they are actively paying attention to something. Some of these measurable tell-tale activities include:

- Heart rate increases when infants are interested in something

- The pace at which they suck on a pacifier quickens with increased interest or attention levels.

For a full discussion of these findings, see Siegler & Alibali, 2019.

Why is Infant Attention Important?

So infants may be drawn to a brightly coloured object, such as a red ball, or to a sound that is pleasing to them and turn their gaze towards such stimuli to “pay attention” to them.

Why does this matter? It matters because infants will learn about what they pay attention to. It also matters because it shows us that even young infants are engaging with the world: they see differences among objects and people and hear differences among sounds they hear. In this way, infants are not simply passive in their environments; they are actively engaged in their world, with their minds drawn to different things in different ways.

In early education, we must be aware of this attention and engagement because we are then aware of how interactive attention is and, therefore, the important role we play in the development of children’s attention. Together, we explore things and people in ways that expand upon stimuli in which infants are already interested, or we guide them towards things that we deem important in some way for them to process.

What Do Infants Pay Attention To?

Western researchers have identified things that many infants prefer to look at in their environment or that we could say they pay attention to. Siegler and Alibali (2019) and Gauvin (2022) both cite research indicating young infants are drawn to novelty, motion, and graphic lines (especially the outlines of shapes and objects), but particularly human faces and voices. Interestingly, Gauvain (2022) interprets the way infants are drawn to faces as something that “allows the infant to learn about social interaction by participating in it” (p. 22).

Novelty, the idea that something new will be more interesting than something already known, provides an insight into just how much infants can pay attention. Infants may look at something new and find it stimulating, so they continue to look, but then they may grow tired of that stimulus and look away. This process of an infant “getting used” to seeing or hearing something so they are not that interested anymore is called habituation.

Watch the video below, which explains habituation through an experiment using a visual preference technique from experimental psychology. Then, complete the knowledge check below the video.

Video: Infant Looking Time Habituation (duration: ~7 mins from 1:05 to end).

Captions were not provided for this third-party video, but YouTube’s auto-caption feature is enabled. If you require a transcript, please inform your instructor.

(Vishton, 2009)

Knowledge Check

Another way experimental psychology has looked at attentional ability is through how it develops. Human interaction and survival are fundamental to that development (see Tomasello, 2016). It is not that infants need to learn to interact, but rather their very survival depends on it; unlike a sort of skill that needs to be learned with the infant’s cognitive capacity, it is instead inseparable from learning itself.

While Western experimental psychologists have provided insights into these preferences, and we can draw from them to provide infants with particular types of stimuli they tend to prefer, we must also look at how other perspectives have identified the social interactions of infants as the very mechanism for the development of attention.