34 Theoretical Perspectives on Problem Solving

From Concrete to Abstract

Siegler and Alibali (2019) consider problem-solving from two perspectives in their chapter: physical and abstract. Their text revisits a theme of movement from the concrete to the abstract in cognitive development, which is particularly salient for the area of problem-solving.

Think about the image above of a child engaged in doing a puzzle. The problem to be solved is fitting pieces together to form a larger image. From a very early age, toddlers are engaged in problem-solving of this concrete variety (e.g., stacking blocks so they do not fall over; or fitting puzzle pieces into a board with shapes).

When children develop concepts and have mental representations of things they see in the world, they can also use those to solve problems. Therefore, we can think of problem-solving as being concrete in some cases and abstract in others. Siegler and Alibali discuss how infants begin in more concrete ways and gradually move to the abstract.

This idea of moving from the concrete to the abstract actually has its roots in Vygotsky. Vygotsky (1987) was very much interested in higher-order thinking and the role that language played in it. He proposed that young children engage in social interactions with various cultural tools and that early on, they are typically physical tools used for something practical — like fitting together puzzle pieces or stacking blocks.

However, as young children acquire language, they are able to think more symbolically. They can begin to refer to things that have not yet happened or that are not present in view with others around them.

In fact, the process by which they learn to problem solve is largely influenced by internalizing language spoken to them by older children or adults around them. In this way, language helps children to go beyond the present physical situation to mentally contemplate possibilities, share knowledge, and then have that interaction impact how children carry out even physical tasks in a practical way.

Through the use of cultural tools in interactions with others, problem-solving can involve the manipulation of ideas — not just blocks or puzzle pieces.

The Zone of Proximal Development

What is in the zone of proximal development today will be the actual developmental level tomorrow

— Vygotsky (p. 82)

Problem-solving was very central to Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory. He emphasized higher-order thinking, such as language and problem-solving, as central to how thinking develops. What is interesting about this model is that it requires interaction with others and the world.

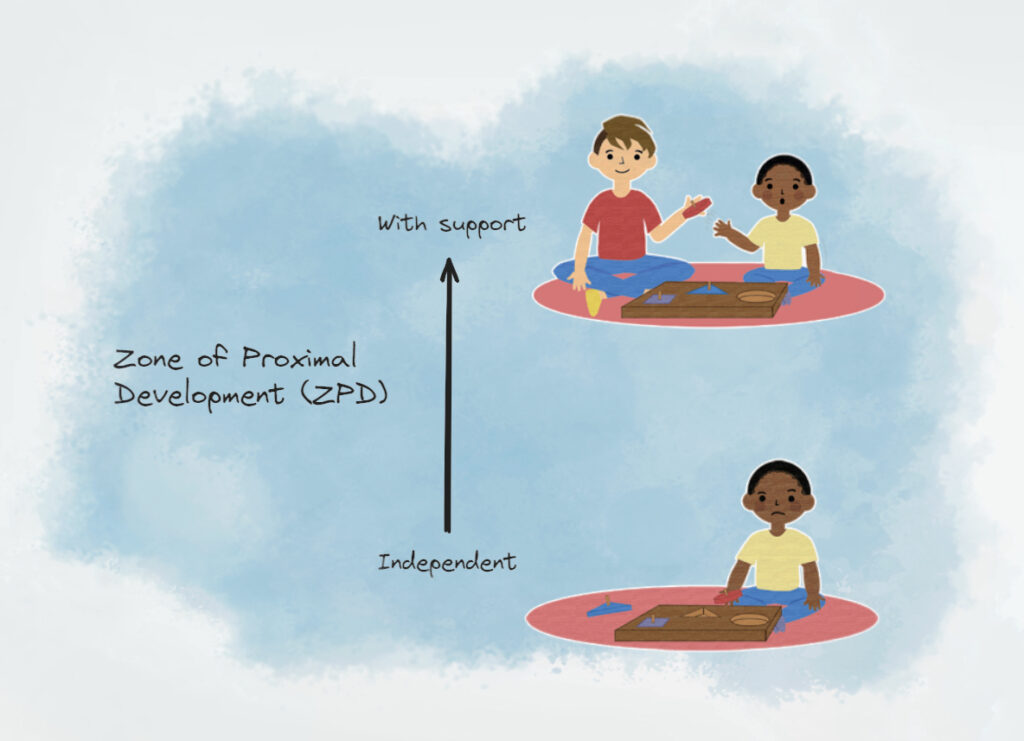

This leads us to a term of Vygotsky’s (1978, p. 84) that you probably remember from our discussions of theory in Chapter 2: the zone of proximal development (ZPD). Over the years, my own paraphrasing of how older children and adults support the thinking skills of younger children in the ZPD has been something like this:

The distance between what a child can do by themselves and what they can do with the assistance of others.

And I would typically draw this out graphically on the board as follows:

The more “official” definition of the ZPD is found in Vygotsky’s Mind in Society (1978):

“…the zone of proximal development…is the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers.” (p. 86)

Before we pivot from theory to practice, I want to draw your attention to the video below of a toddler stacking blocks while his parents watch.

Video: Problem Solving (duration: 1:10)

Reflection Journal

Reflection 6.2a: Describe in a few sentences what happened in the video.

Reflection 6.2b: What do you think might have happened next after the video recording was stopped? Relate your answer to the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).