31 Eastern Perspectives on Memorization

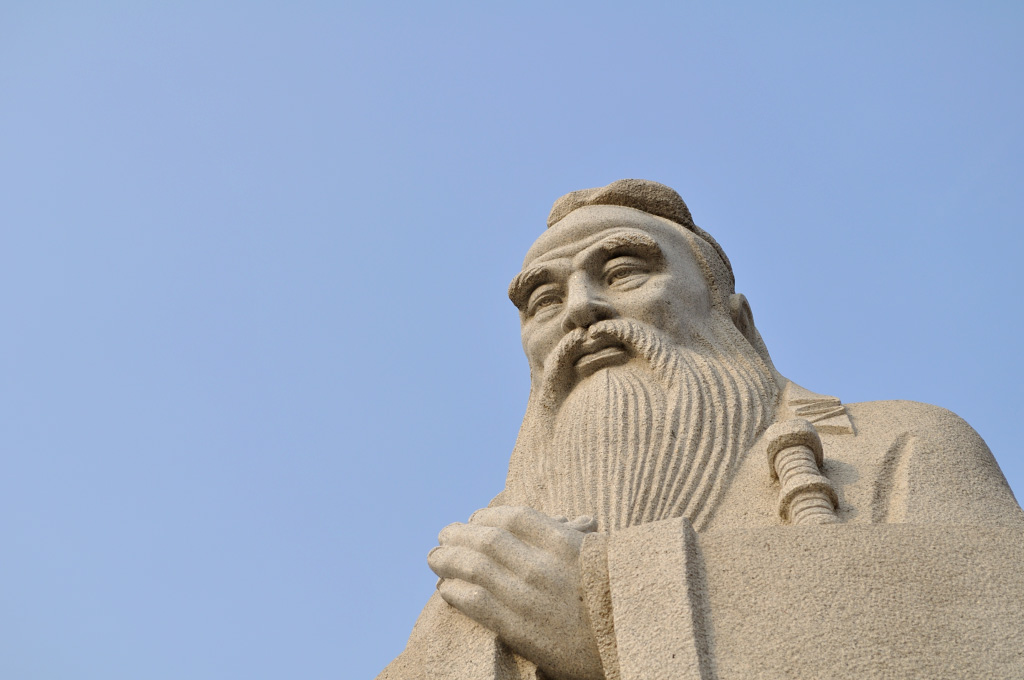

In The Analects of Confucius (Ames & Rosemont, 1998), both imitation and memorization are explicitly discussed as mechanisms for memory, cognitive development, and learning in general. Such ideas may fly in the face of Western models of play-based learning (see Ahn, 2023 for a discussion), but they are ancient components of the most influential philosophical tradition of the Far East.

As is the case with many big ideas, particularly of a philosophical nature, it can be hard to apply them in practical, day-to-day ways in the classroom. Either due to this theory-to-application gap or perhaps due to a philosophical clash between the East and the West, imitation and memorization are not highlighted in the main pedagogies of early childhood. While we revisit these ideas in Chapter 8, for now, we will consider how this clash might be impacting the Western interpretation of the value (or lack thereof) of imitation and memorization.

In Charlene Tan’s (2015) exploration of the Confucian concept of thinking, she identified a Western bias that I, as a Westerner, have indeed heard over the years: that learning in East Asia is related to “reproducing exactly what is taught” (Dunbar, 1988, as cited in Tan, 2015).

However,Tan questioned this interpretation of Eastern learning and what, exactly, Confucius was proposing by referring to one of the most famous Confucius texts, the Analects. Tan helpfully outlines how Confucius viewed thinking (si) as embedded in his view of learning (xue), and that si embodied many higher-order processes (e.g., “understanding, reflection, analysis, synthesis” [p. 430]). This is a surprising parallel to this textbooks’ core position: one has to look at learning to understand thinking (hence this textbook’s title: “Children’s Learning and Thinking”). Confucius emphasized the joy that one should gain from learning for learning’s sake and to guide society forward — this is hardly an emphasis on rote memorization of the previous ideas of others.

So where does this idea come from that East Asian models of thinking and learning prioritize memorization, and what does this mean for early learning?

Indeed, as Tan (2015) points out, Confucius did see a place for it as one of many tools in learning. He recommended memorizing the poems from the Book of Songs to reflect on them and internalize them so you can relate them to your daily life. This is a fascinating parallel to studies done in the West on storytelling that found the very structure of stories to support meaningful memories of events (e.g., Kulkofsky, Want and Ceci, 2008).

By no means am I able to convey the complexity of Confucianism in learning in this chapter, but understanding the use of memorization as a tool for other kinds of thinking is a powerful concept that, in my opinion, has been largely extracted from Western models of thinking and learning.

Also, young children must memorize Chinese characters in large amounts in order to become literate — this task alone is far greater than memorizing the 24 letters and sounds of the English version of the Roman Alphabet. Therefore, it is a practical reality that memorization must be integrated into early learning, but it must be for all children; we will revisit this at the end of the book when we discuss learning models.