Chapter 3 – Respiratory System Assessment

Posterior and Lateral Thorax – Auscultation

Auscultating the posterior and lateral thorax involves the following steps (see Video 3.5):

Step 1: Perform hand hygiene and cleanse the stethoscope.

Step 2: Ensure the client is in an upright position and ask them to take a big breath in and out through the mouth each time they feel the stethoscope on their posterior thorax.

-

-

- Instruct the client to breathe through the mouth because this makes it easier for you to listen to lung sounds, particularly if there is any nasal congestion or obstructions.

- Keep in mind that breathing a bit more deeply may trigger shortness of breath or dizziness for some clients. You should notify them that they can take a break and breathe normally if they need to. Also be aware that older adults may have difficulty taking a big breath.

-

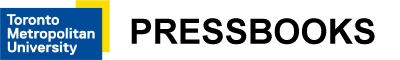

Step 3: Place the stethoscope’s diaphragm on the chest in about four to eight locations on each side of the posterior thorax and then at three locations on the right lateral thorax and at two locations on the left lateral thorax so that you listen to all lung lobes. Make sure you have a complete seal. See Figure 3.11 for the placement pattern. The number of locations depends on the size of the thorax. For example, less locations are needed on a client with a smaller thorax (e.g., infants). Note that the posterior thorax is primarily lower lobes.

-

-

- On the posterior thorax, begin at the shoulders at the scapular line, moving from one side to the other side, then move down, and repeat. As you move down the thorax, place your stethoscope close to the vertebral line so that you avoid listening over the scapula. Toward the bottom, listen close to the vertebral line and also move laterally.

-

Figure 3.11: Placement pattern for auscultation of posterior thorax

Image by Claudio_Scott from Pixabay (image was cropped and illustrated upon for the purposes of this chapter)

-

-

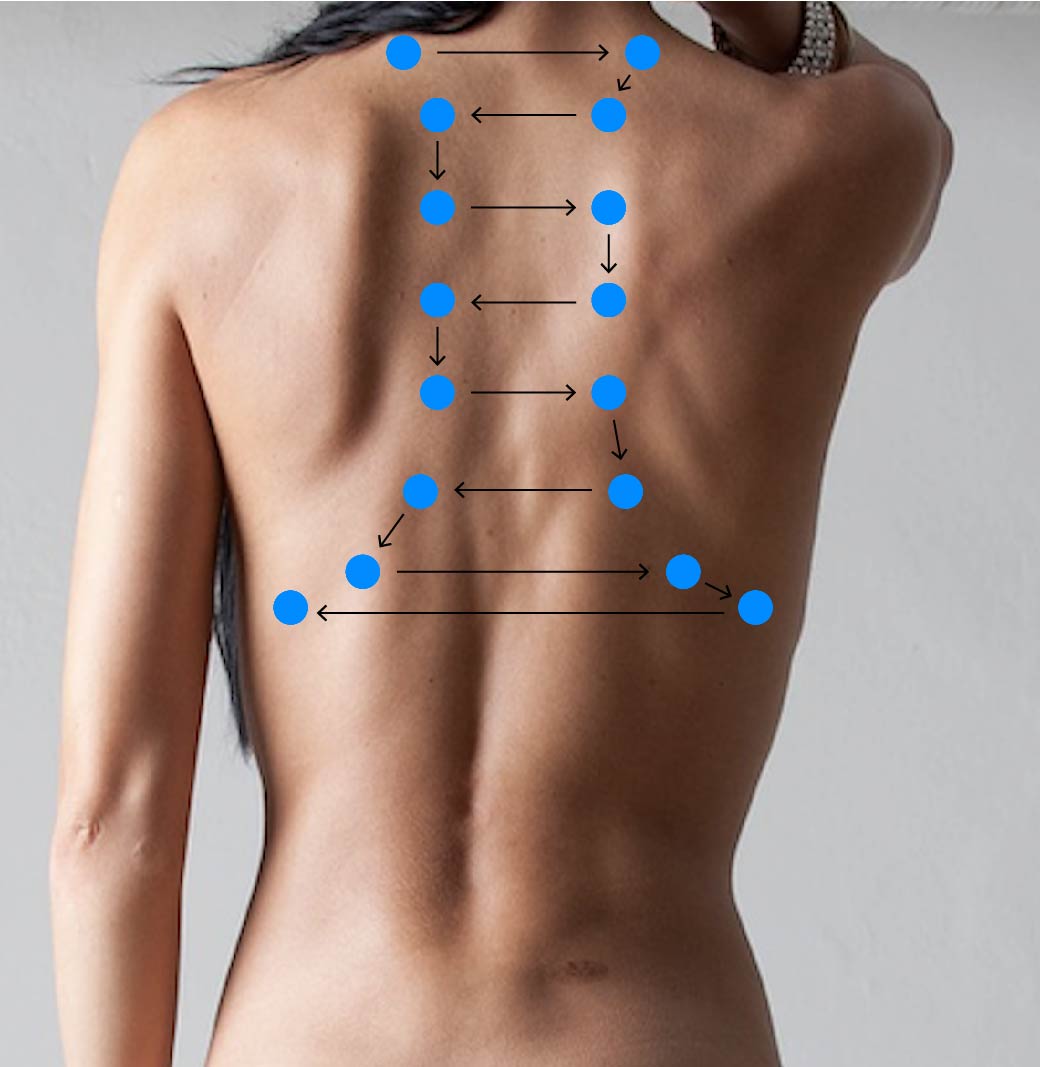

- On the lateral thorax, place the stethoscope at three locations on the right side so that you listen to the right upper, middle, and lower lobes, and then two locations to listen to the left upper and lower lobe. See Figure 3.12 below.

-

Figure 3.12: Placement pattern for auscultation of lateral thorax

Step 4: In each location, listen to one full respiration (inspiration and expiration) and compare air entry bilaterally.

Step 5: Listen for the following:

-

-

- Air entry quality and equality.

- Quality: Note whether it is good, decreased, or absent.

- Equality: Note whether air entry is equal bilaterally.

- Air entry quality and equality.

-

- Normal breath sounds including clear air entry and the location of bronchovesicular and vesicular.

- Air entry is normally clear with no abnormal sounds (e.g., adventitious breath sounds – see below)

- Bronchovesicular breath sounds are moderate in loudness; inspiration is equal to the expiration phase, and heard on the upper thorax close to the vertebrae and near the bronchi.

- Vesicular breath sounds are quiet and low-pitched; inspiration is longer than the expiration phase, and heard in the periphery of the lung fields and near the smaller airways in an older child and adult. (Note: in young children particularly under two and three years of age, vesicular sounds are not heard because of their small thoraxes. Rather, you hear bronchovesicular over the whole thorax).

- Normal breath sounds including clear air entry and the location of bronchovesicular and vesicular.

-

NOTE: When a person takes a breath in, it takes time for the air to get to the periphery of the lung fields resulting in a long inspiration phase. When a person breathes out, the expiration phase is short with vesicular sounds because the breath leaves the periphery of the lung fields quickly.

NOTE: Another type of normal breath sounds are bronchial sounds, which are heard over the tracheal area. These sounds are described as hollow sounds and harsh sounds, particularly upon expiration; the expiration phase is longer than the inspiration phase. These are heard over the trachea area, and are not heard on the posterior thorax except in the case of an underlying pathology.

Audio 3.1: Normal breath sounds

-

-

- Adventitious sounds are abnormal lung sounds with several causes. You will become familiar with the quality of these sounds after listening to the thorax of many clients and listening with an expert nurse. When you hear these sounds, you should note the quality and the location. For example, what lobes do you hear these sounds in?

- Wheezes are an adventitious sound heard in the lungs when there is bronchoconstriction (i.e., narrowing of the airways) that can happen with inflammation and with conditions such as asthma, emphysema, or an allergic reaction. Wheezes are a continuous musical-like sound that can be heard on inspiration or expiration and can be low- or high-pitched. Higher pitch = increased bronchoconstriction. Lower pitch = decreased bronchoconstriction. Wheezes are often described as mild, moderate, or severe.

- Adventitious sounds are abnormal lung sounds with several causes. You will become familiar with the quality of these sounds after listening to the thorax of many clients and listening with an expert nurse. When you hear these sounds, you should note the quality and the location. For example, what lobes do you hear these sounds in?

-

Audio 3.2: Adventitious sounds: Wheezes

-

-

-

- Stridor is a more extreme form of wheezing when the upper airways are partially obstructed, and have congenital (i.e., problem present at birth), infectious (e.g., croup, bronchitis), or trauma-related (e.g., foreign body, neck fracture) causes. The sound is continuous and high-pitched. Although commonly heard on inspiration, it can be heard on expiration too. It is usually associated with other signs of respiratory distress and requires immediate response.

-

-

Audio 3.3: Adventitious sounds: Stridor

-

-

-

- Crackles are an adventitious sound heard in the lungs when there is an accumulation of fluid (e.g., mucus), such as with pneumonia. They sound like an interrupted popping and even a bubbling noise that can be described as fine, moderate, or coarse crackles depending on the severity. Mild crackles are typically heard in the bases because fluid accumulation in the lungs is affected by gravity. Crackles are typically heard upon inspiration, but they may be heard upon expiration and heard throughout the thorax, particularly when the crackles are coarse. Coarse crackles are associated with increased severity in terms of fluid accumulation in the lungs.

-

-

Audio 3.4: Adventitious sounds: Crackles

Step 6: Note the findings:

-

-

- Normal findings might be documented as: “Good air entry, equal bilaterally, no adventitious sounds audible throughout all lobes. Bronchovesicular sounds heard in upper lobes close to vertebrae. Vesicular sounds heard throughout periphery and lateral lobes.”

- Abnormal findings might be documented as: “Decreased air entry heard in left lower lobe with moderate crackles.”

-

Video 3.5: Auscultation of posterior and lateral thorax

Clinical Tip

If a newborn or young child is sleeping, begin with auscultation. It is difficult to accurately listen to lungs when a client is crying. If a client is crying, consider ways to reduce this. For example, a newborn/young child will feel safer if the parent/care partner is engaged. You could have a young child play with your stethoscope so that it is familiar, or ask them to take a big breath and pretend they are blowing out birthday candles.

Priorities of Care

Absence of air entry and stridor are considered urgent situations. You should notify another provider like a physician or nurse practitioner. If you think the stridor is caused by a foreign body that you can quickly remove, do so. Otherwise, follow the steps of the primary survey (check airway patency, measure respiratory rate, work of breathing, and oxygen saturation, assess pulse rate/rhythm, blood pressure, assess level of consciousness). If the oxygen saturations are low, apply oxygen if you are permitted to do so.

With the presence of crackles and wheezes or decreased air entry, you should rely on the primary survey to determine whether there is a risk of clinical deterioration. You should also consider whether the wheezing is new onset and could be caused by a severe allergic reaction (i.e., anaphylaxis) and requires immediate intervention. If not, and the client is stable, you can move the head of the bed up to assist with breathing and continue the focused assessment on the respiratory system. Abnormal findings should be reported.

refers to muscles surrounding the airways spasm/contract.