Module 1: Types of Reviews

Conducting a Systematic Review

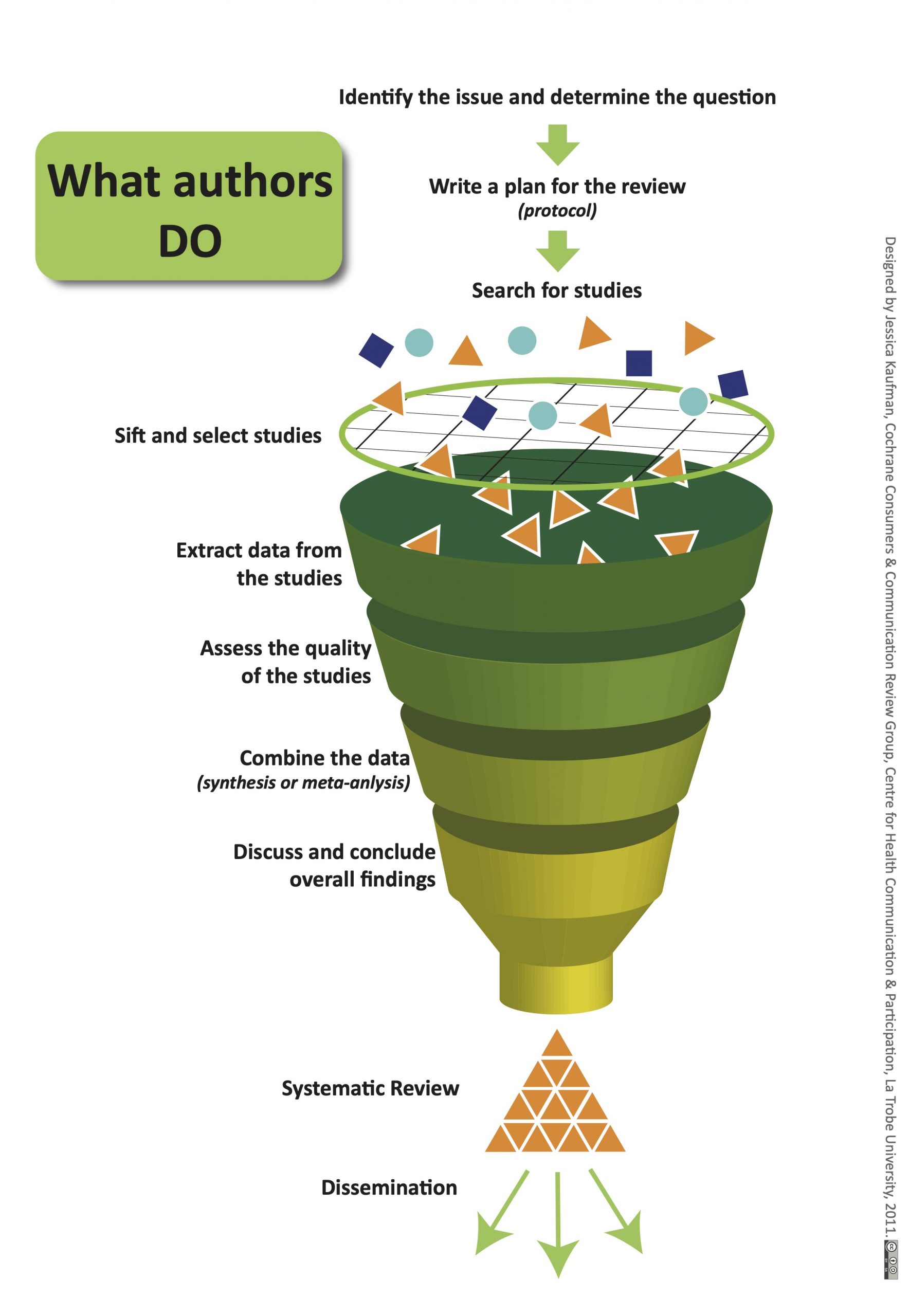

This section is a quick summary of the main steps involved in conducting systematic reviews. By the end of this section you should have a better idea of the time and resources needed to conduct a successful review.

All reviews follow a familiar process as seen in Figure 1.1 below.

Find Existing Systematic Reviews

Prior to starting your own research, you will want to look at existing systematic reviews – this is especially important so that you don’t duplicate existing work. It can also be helpful to look at the approaches taken for systematic reviews similar to your own topic or discipline. You can find existing systematic reviews through a number of ways:

- Search published journal articles. Systematic reviews can be published as journal articles. To identify them, add “systematic review” as an additional search term in databases, or look for publication type limits, if available. Here’s an example of a “systematic review” published as a journal article.

- Search “Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews” through your library. This database includes the full text of the regularly updated systematic reviews of the effects of healthcare prepared by The Cochrane Collaboration.

- Search different registries. For example, PROSPERO is an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care, welfare, public health, education, crime, justice, and international development, where there is a health related outcome. PROSPERO aims to provide a comprehensive listing of systematic reviews registered at inception to help avoid duplication and reduce opportunity for reporting bias by enabling comparison of completed reviews with what was planned in the protocol.

- Search the Campbell Collaboration. The Campbell Collaboration is an international network which publishes high quality systematic reviews of social and economic interventions around the world.

Key Takeaways

Looking at published reviews and protocols can give you an idea of what has already been done and will help you ensure that your own research is original.

Assembling Your Research Team

If you are conducting a systematic review that requires a team these are the typical roles involved:

- Reviewers – You may need at least two reviewers working independently to screen abstracts, with a potential third as a tie-breaker

- Subject matter experts – Subject matter experts can clarify issues related to the topic,

- Statistician – A statistician can help with data analysis

- Project leader – A project leader can coordinate and write the final report

- Librarians – Librarian(s) can develop comprehensive search strategies and identify appropriate databases

Formulate Your Research Question

In general, your research question will tackle the problem you are trying to address by conducting the review. Since constructing a research question can be an in-depth process, we go over it in more detail in Module 2: Formulating a Research Question and Searching for Sources.

Create a Review Protocol

Reviews like a systematic review require a protocol, which is essentially a planning document that indicates how your review will be carried out. Here is a sample protocol template from the Evidence Synthesis Coordinator at the Maritimes Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Support Unit. This basic form includes all the relevant information needed for a simple protocol.

You may wish to register your protocol to avoid the duplication of work and to reduce the potential for bias by enabling a comparison between what was stated in the protocol to the completed review. It is also a way to share your current research interests with the research community at large, and help build your research profile.

Example

How to Register your Protocol:

Please see this guide by the National Institute of Health (an agency of the United States government): Systematic Reviews Protocol and Protocol Registries.

Key Takeaways

By creating a protocol you are creating a document that will guide you through the systematic review process. Always refer to it throughout the process to ensure you are on track.

Conducting Your Review Using the SALSA Framework

Once you have a research question, there are four stages you can follow when conducting your chosen review. These are known as the SALSA Framework: search, appraisal, synthesis and analysis.

Example

Here is a quick summary of the SALSA steps.

Wait, What Happened to the “L” in SALSA?

Did you notice the missing L? We did too! The authors, Grant and Booth (2009) created a simple analytical framework for conducting reviews: Search, Appraisal, Synthesis and Analysis. SASA, however, doesn’t make a memorable acronym, and Academics love a good acronym, so they derived the “L” from the last letter of appraisal: Search, AppraisaL, Synthesis and Analysis (SALSA).

Example

Applying the SALSA Framework to Your Specific Review

We’ve provided a quick summary of the framework, and once you have chosen your specific type of review you should consult the following chart by Grant and Booth (2009) for a deep dive into each stage of the SALSA framework for your specific review.

A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. [1]

PRISMA: The Systematic Review Checklist

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PRISMA is the recognized standard for reporting evidence in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The standards are endorsed by organizations and journals in the health sciences. It allows other researchers to assess strengths and weaknesses of the review and assists with future replication of the review methods. The 2020 PRISMA statement consists of a 27-item checklist and a 4-phase flow diagram.

Example

For more information, consult the PRISMA Explanation and Elaboration document.

If you are conducting a scoping review, see The PRISMA-ScR (PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews)

Key Takeaways

A large amount of time and resources go into conducting a systematic review. To make sure you are ready to carry out a review, use the Knowledge Synthesis Readiness Checklist from Unity Health Toronto.

- Citation: Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x ↵

A systematic review protocol describes the rationale, hypothesis, and planned methods of the review. It should be prepared before a review is started and used as a guide to carry out the review.