Module 4: Ableism and Accessibility

Key Concepts in Ableism and Accessibility

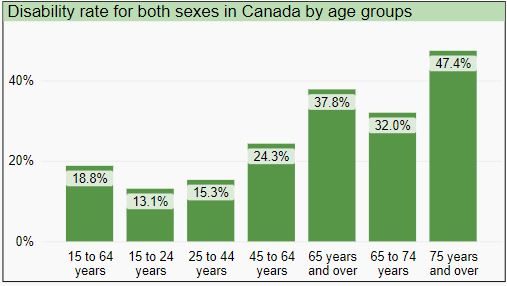

Globally, the WHO estimates that 15% of the total world population is disabled (“Strengthening the Collection of Data on Disability“). In Canada, represented through the graph, Statistics Canada estimates 22% of the population 15 years and older is disabled. The proportion of people with disabilities rises with age, and the rate for females (24.3%) is higher than males (20.2%), as shown in Figure 4.1 (Scott et al.).

Despite these prevalence rates, there is no consensus around the definition of disability, which signals its fluidity (Trybus et al. 61). This mutually dependent relationship is represented by terms like dis/ability, (dis)ability, and ability/disability (Schalk 6). By extension, disability cannot be understood without understanding ableism.

What is Ableism?

Campbell defines ableism as “a network of beliefs, processes and practices that produces a particular kind of self and body (the corporeal standard) that is projected as the perfect, species-typical and therefore essential and fully human” (5). Ableism perpetuates attitudinal behaviours, misconceptions, and negative assumptions that assign inferior value to people with disabilities. It reflects judgements by the dominant group (able-bodied people) over which human qualities and characteristics are desirable and which are feared and devalued (Kanter 417). It leads to discrimination and exclusion. People with disabilities face barriers in society, whether systemic, attitudinal or physical, and these experiences are exacerbated due to ableism. It affects disabled people and anyone who appears to be disabled.

“Ableism exists at all levels of society and can manifest. Click on each of the following to learn about the ways in which ableism can manifest”:

Examples

While often used interchangeably with disablism, there are nuanced differences. Disablism, like racism, sexism or classism, recognizes that persons with physical, sensory or cognitive impairments are marginalized based on these differences and linked with processes that (re)produce inequality (Goodley 16). Both terms convey discrimination, but ableism favours non-disabled persons, while disablism centres on discrimination against persons with disabilities.

In an interview, Elsa Sjunneson, who self-identifies as a deafblind woman, describes ableism as the way:

“Non-disabled people make the world unsafe for disabled people. It is a social structure that gets used to hurt people. So it’s important for non-disabled people to learn about because much like other -ism’s, it’s a system that directly benefits non-disabled people…” (“Q&A with Elsa Sjunneson”).

Sjunneson stresses the importance of learning about ableism. This requires more than a pamphlet on disability etiquette and a how-to guide for interactions with persons having disabilities to prevent inappropriate, unwelcome and intrusive questions. It involves troubling the economic, social, and epistemic (knowledge) structures that promote particular conceptions of persons with disabilities.

Reflection

How Does Ableism Affect Your World?

After reading about ableism and how it can manifest in many forms, what are some examples of ableism that you have experienced personally or may have observed or witnessed?

Models of Disability

Models make sense of complex phenomena. Models of disability help to explain social dynamics and behaviours governing relations between persons with disabilities and non-disabled persons and contributing factors, including historical, political, cultural, economic, and epistemological factors. Bickenbach writes that “conceptualizations are not facts that can be shown to be true or false; they are constructions for organizing our thoughts…” (53). Which model an individual leans toward will depend on their ideological preferences and biases, the inherent persuasiveness of a model and how it holds up against scrutiny and testing. At least six models shape public understanding and private dispositions and behaviours. These are:

We will be focusing on the Medical Model and the Disability Justice Model in the following pages. To further your personal understanding of the other disability models, explore the links above.

The Medical Model

The medical model centres on diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. It is made possible by networks of medical and scientific researchers, clinical practitioners, corporations, and professional associations. They design, produce, test, and approve medical technologies and practices designed to, at best, cure and restore to “normal” and, at worst, do no harm. This model reinforces binaries like normal/abnormal, typical/deviant, disability/ability through measurement and classification systems.

Scientific knowledge is often incomplete, flawed and may lead to injury and harm, either deliberate or unintended. For example, eugenicists in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries propagated the notion of a hierarchy of races based on cranial measurements that justified the enslavement of Black and Indigenous peoples and rationalized the forced sterilization of racialized women. Some have referred to this period as “old eugenics” in contrast to the “new” eugenics (Sparrow 32) represented by technologies like genetic editing tools such as CRISPR genetic scissors. In awarding the 2020 Nobel Prize for Chemistry to the inventors of CRISPR, the Nobel Committee stated that CRISPR enables researchers to alter the DNA of microorganisms, plants, and animals with precision. “This technology has had a revolutionary impact on the life sciences, is contributing to new cancer therapies and may make the dream of curing inherited diseases come true” (The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences). By glimpsing a world where human enhancement is made possible, genetic diseases are eliminated and perfection is attainable, CRISPR (and other medical technologies) raises moral and ethical questions regarding what characteristics are valued, and who should make these decisions (see Michael Sandel’s The Case Against Perfection).

The medical model is encoded with conceptions of normal/abnormal and made possible through statistics and specialized knowledge, which confers the power to label and categorize people. Labelling risks of “othering” by constructing persons as “less than” and “needing fixing.” Such constructions are reflected and reproduced through cultural practices, and justify the institutionalization of persons with disabilities. For these reasons, the medical model has been criticized for dehumanizing persons with disabilities and perpetuating the notion that they constitute a “defective class” (Davis 37).

In this excerpt from a public lecture, Grappling with Cure, Eli Clare shares his enduring contact with the medical model. He recalls the evolution of labels such as “feeble-minded”, “moron”, “imbecile” and now “developmentally delayed” or “intellectually disabled.” Clare contemplates what it means to be normal/abnormal, and how these archetypes morph through language and “expert” knowledge that is authoritative and unassailable.

This model conceives people as individual, autonomous beings that fit into one of two groups – disabled or able-bodied/minded. It emphasizes the role of curative and rehabilitative treatments that enable persons with disabilities to restore or proximate normalcy. They tend to marginalize the knowledge and lived experience of persons with disabilities and the role of stigma in perpetuating unequal power relations. Through binaries of normal/abnormal and self/other identities, they reinforce power inequalities that govern relations and possibilities. We turn next to the Disability Justice model, which centres on participation, highlighting how to achieve the full participation of persons with disabilities in public life.

The Disability Justice Model

Whereas rights-based and social models work within existing political-economic systems, disability justice activists make explicit their anti-capitalist stance and intersectional approach (Goodley 637). Neoliberal capitalism fetishizes an individual who is an autonomous, rational, work-ready, entrepreneurial, economically productive consumer. Conversely, it names those who cannot proximate this standard as inadequate, inferior, and flawed. Whereas the Disability Justice framework understands that all bodies are unique and essential, and “have strengths and needs that must be met” (“What is Disability Justice?“). For Disability Justice activists, the answer lies in structural change, not just better enforcement mechanisms, or anti-discriminatory practices. They advocate for coalition building across diverse equity groups and issue areas, including eco-ability – which rejects the view that the non-human species and the natural environment can be commodified and claimed as human property (Bentely et al.). It works towards collective justice and liberation for the transformation of society as a whole.

Activists, organizers, and cultural workers working in the field of disability justice recognize that able-bodied supremacy has evolved in connection to various systems of dominance and exploitation. White supremacy and ableism are inherently connected histories, both of which emerged in the context of colonialism and capitalist dominance. White supremacy uses ableism to create an inadequate/”other” group of people who are deemed less worthy/abled. A single-issue civil rights framework is inadequate to explain the full picture of discrimination against persons with disabilities and how it works in society. Discrimination against persons with disabilities can only be truly understood by tracing the relationship with discrimination against persons with disabilities, heteropatriarchy, white supremacy, colonialism and capitalism. The same oppressive systems that have been inflicting violence on Black and brown communities for 500 years have also been inflicting brutality on bodies and minds that do not fit the norm (“What is Disability Justice?“).

By recognizing how social ideas about normal/abnormal are internalized and affect their self-image and opportunities, persons with disabilities have reclaimed and reimagined labels like “crip” and “cripping” – derived from the derogatory “cripple.” Crip is expressive of resistance. It is used as both a noun and verb to denote a particular identity, like crip-queer and crip-femme. “Crip time” or “cripping time” is not about slowing things down, but valuing alternative modes of doing, thinking and being. Crip theory, at its core, centres on expanding our notion of being human by bending archetypes of what it means to be normal, valuable, and desirable (McRuer).

The disability justice model centres on new social structures and not on the eradication of disability (Dolmage 2). New forms of understanding ability/disability will be achieved only through resistance. The disability justice model does not aim to eliminate or assimilate disability into some definition of normality. Instead, it carves out a space for a common understanding that expands understandings of what it means to be human.

Overview of the Legal Rights-Based, Social and Disability Justice Models

The legal model establishes the laws, norms and rules that facilitate the participation of persons with disabilities in public spaces, including schools and workplaces. The social model focuses on barriers to accessing opportunities through inclusive design and accommodation. It places responsibility for disclosure and negotiating accommodation largely on individuals. Justice- and equity-centred scholars and activists argue for reimagining disability as human variation and a more expansive understanding of accessibility. Proponents of the justice model represent queer, feminists, Black, Indigenous, and other racialized groups who argue for remaking systems of oppression. In other words, proponents of the social model focus on assimilation through training in self-advocacy and disclosure; the rights of disabled persons and the duties of employers contribute to liberal assimilation. In contrast, a justice-centred approach imagines a radical transformation and a reinterpretation of the relationship between persons, and between humans and the environment and non-human animals.

Test Yourself

How Much Do You Know?

The charity model conceives disability as a deficit that dictates the benevolence of strangers. It is exemplified by advertising campaigns showing persons with visible impairments like cleft lip, amputation, blindness, and leprosy.

The medical model centres on diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. It is made possible by networks of medical and scientific researchers, clinical practitioners, corporations, and professional associations that design, produce, test, and approve medical technologies and practices designed to, at best, cure and restore to “normal” and, at worst, do no harm. This model reinforces binaries like normal/abnormal, typical/deviant, disability/ability through measurement and classification systems.

The legal, rights-based model of disability centres on a universal conception of human rights as codified in the International United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations). Persons with disabilities are rights-bearing persons capable of claiming their rights and making decisions based on free and informed consent (United Nations, n.d.). In other words, the Convention affirms the motto “No decision about us without us.”

The supercrip model promotes heroic tropes embodied in both fictionalized characters and persons. For example, Matt Murdocks Dare Devil and Terry Fox. Although this model tries to displace stereotypes of pitiable, powerless victims with a positive, idealized image, it does not lend itself to nuance, contradictions, or complexity. These narratives often neglect the circumstances that enable supercrips to be exceptional including race, gender, or class privilege and devalue the lives of persons with disabilities which do not match up with the glorified image (Schalk 80).

The social model emerged in the 1970s, and challenges medicalized and individualist accounts of disability. It differentiates between disability from impairment. Impairment is the physical/material reality (a medical condition affecting a body); disability is socially constructed through discriminatory attitudes and practices that deny people’s access to social and physical spaces and are not the result of individual deficit.

Disability Justice Model/Framework examines disability and ableism with an intersectional approach. It understands disability as it relates to other identities and various systems of oppression.