Module 1: Key Concepts in Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

Self-Advocacy

This section looks briefly at response strategies for microaggressions and allied relations. There is no magic bullet. Responsibility for blunting racist, sexist, homophobic, ableist thoughts and actions is shared between individuals, organizations, and society. The aim of these modules is to gain knowledge, awareness and skills that will enable learners to take effective actions that combat discrimination and create more inclusive and safe environments, so the experience of learning is a rich one with opportunities for you bring your full creative self too and be meaningfully engaged. It is acknowledged that the power dynamics between the student who may be experiencing or witnessing discrimination and the perpetrators who may be in a position of authority or status (this can also be another peer) can make challenging or speaking up difficult and sometimes scary. There are different factors that weigh into a person’s decision to act and are not always clear-cut reasons nor are they the same for everyone. Whatever the reason, the decision you make should be one that you are comfortable with.

Being informed about the options available to you can help you to determine how you wish to respond and the steps that can be taken, the supports available and the possible outcomes. In some circumstances, the decision to address concerns and incidents does not rest with only you. Once a disclosure is made, processes to respond to situations of discrimination or harassment are triggered such as an investigation or duty to report and respond, as impacts can go beyond individuals directly involved impacting the large group or organization.

Deciding how to respond does not have to be a decision you make on your own and without support. You are encouraged to reach out to program faculty and staff within your institution. There may also be a variety of campus services from which you can also seek advice, will assist you with getting connected to the proper supports and bringing a complaint forward. Remember you do not have to handle things on your own.

Response Strategies to Microaggressions

If you express microaggressions, it is important to recognize and acknowledge the harms of these actions, to interrogate underlying biases, and to take corrective action. So, if you are called out for your actions, resist reacting defensively and denying culpability. Instead, acknowledge that your behaviour has harmed others, whether intentional or not. Consider why you chose to express yourself in a particular way and what underlying assumptions might have informed your response.

If you are the target or a witness of microaggressions, you might consider engaging with various response strategies, including (Houshmand et al. 6; Sue et al. 135):

- Calling out perpetrators by naming the behaviour

- Seeking support

- Educating the perpetrator

- Choosing to avoid and not to engage

- Responding with humour

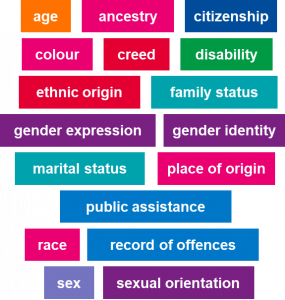

Take a look at Figure 1.2 below for the Ontario Human Rights Code grounds for protections.

Anti-Oppressive Struggles and the Role of Allies

Academic and practitioner interest in allies and allyship has emerged in the context of resurgent social movements like #IdleNoMore, #BlackLivesMatter, #disability justice, among others. The term, “allies”, is derived from the Latin “alligare” meaning “to bind to.” In social movement research, allies refer to individuals and groups representing historically dominant groups who share a commitment to the core principles, values, and outcomes of a campaign, or social movement organized by historically marginalized groups. Examples of allyship include men allied with the feminist movement, White men and women allied with the Black civil rights movement, and heterosexual allies of queer liberation movements. Allies might not agree on all issues, but there must be some minimum threshold for mutual understanding to be compatible and a depth of commitment that renders a readiness for sacrifices to effect social change. These alliances raise a few critical questions, including, can these advantaged individuals/groups be trusted? What are the benefits and risks of allies?

Self-described Chicana, lesbian feminist Gloria Anzaldúa understands allyship as an emotional bond. It means “helping each other heal. It can be hard to expose yourself and your wounds to a stranger who could be an ally or an enemy. But if you and I were to do good alliance work together, be good allies to each other, I would have to expose my wounds to you and you would have to expose your wounds to me and then we could start from a place of openness” (qtd. in Finn 266). Implicit in this understanding is trust. After all, to expose wounds is to reveal vulnerabilities and is reserved for only those whom we trust. The issue of trust speaks partly to the motivations of advantaged groups or individuals, since they come to the struggle from a position of strength. Trustworthiness suggests allied action is motivated by principles and not pity. For example, some self-proclaimed allies might be motivated by a White saviour complex to “help” historically marginalized communities. White saviour complex is not allyship as much as it reinforces patrimonial power relations by assuming that disadvantaged groups are unable to effect social change without the dominant group’s support. As Nova Reid writes with regard to Black social movements, “Black people don’t need white people to rescue us. We don’t. We have been rescuing ourselves and revolting against the oppressor throughout history.” Reid continues highlighting that it is a misconception that Abraham Lincoln, a White man, rescued Black people from being enslaved. However, it was the Haitian Revolution from 1791-1804, the only successful slave revolt in history, that prompted the global abolition of slavery (Reid).

A risk of engaging with allies is that the movement’s agenda might be co-opted by self-proclaimed allies motivated by self-interest. For example, some have described non-profit organizations and individuals that bandwagon on anti-oppressive struggles as constituting an ally-industrial complex (Squire et al. 188). An example includes non-Indigenous students or graduates who accept internships or short-term volunteer placements with Indigenous communities in northern Canada to build their resumes and claim specialized knowledge in Indigenous history, governance systems, and public policies to position themselves strategically for more lucrative positions. Such individuals use opportunities for upward mobility rather than as a mechanism for solidarity. Other examples are non-profit organizations that respond to requests for proposals by donors on trending issues, regardless of their knowledge and capabilities. In such cases, the agenda might be corrupted, subverted, or co-opted into neoliberal agendas.

Part of assessing trustworthiness involves measuring the level of commitment, which may be apparent only through engagement with time. For some, the commitment is superficial. For example, some persons signal solidarity through performances, like a person or business owner who posts an “Every Child Matters” sticker on their door and/or wears an orange T-shirt to memorialize the deaths of Indigenous children at residential schools and the ongoing abuses of the child welfare system. However, they make no effort to learn about Indigenous history or believe it is an inconvenience when a land defence group blocks a railway. Similarly, someone might introduce themselves and the pronouns they use (i.e., “My name is John Smith and I use he/him/his pronouns”) to signal their solidarity with trans* and gender-nonconforming communities, but do not speak out when they overhear a transphobic insult in a bathroom.

Allyship is action-centred and not a rhetorical commitment. Action includes listening, self-education, community building, challenging oppressive structures, and supporting social movements. Understood as an action and not a noun, to ally is to push back against racism and create space for freedom. Allyship is “working alongside, supporting, accepting you are going to get it wrong and showing up, anyway. It means accepting that anything worthy of seismic change will not happen without discomfort, consistency and a whole heap of courage. If someone is in any doubt, they should ask themselves: am I acting because it’s the right thing to do, to centre the needs of others, or am I doing this for myself, to feel better and make myself look good?” (lyer; Reid).

Sojourner Truth (1797-1883) was a Black female activist and emancipated slave in 19th century America. Speaking at a women’s convention in 1851, she delivered a speech titled “On Woman’s Rights”. (Watch a performance of the Sojourner Truth’s speech by Afro-Dutch women or read text of the speech in the Anti-Slavery Bugle Truth defiantly claims her rights, saying:

“…I am a woman’s rights.

I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man.

I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that?…]”

Sojourner Truth demanded to be treated as an equal by affirming the value of women’s work and intellect. Apart from domestic service, Black women participated in agricultural labour alongside Black men. It is inconceivable that such a speech could have been conceived and delivered by a White feminist of that period who did not work in the fields. The speech is notable for another reason, namely the liberties taken by Frances Gage, a White feminist who reconstructed and published the speech in 1863 retitled “Ain’t I a Woman” in support of Black feminists and the women’s movement broadly. The article targeted a mainly White readership, and Gage misrepresents the original text by inflecting it with a heavy southern dialect. For example, she swaps the original title “On Woman’s Rights” with “Ain’t I a Woman”. What motivated her to make these revisions and portray Sojourner Truth in this way remains unclear. But the edits insinuate a deliberate effort to subordinate Sojourner Truth (and Black feminists more broadly) to White feminists through language that conforms to White frames about how Black women speak. (The two speeches are presented side-by-side by The Sojourner Truth Project.)