Chapter 3 – Consumer Behaviour: How People Make Buying Decisions

3.2 Consumer Decision Making Process

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Understanding the stages of the Consumer Decision Making Process.

- The implication of the product disposal.

The Consumer Purchase Decision Process

The Consumer Purchase Decision Process is used to describe purchase behaviour and acquisition behaviour. It has also been used to explain the decision process for purchase behaviour as well as the process that a person goes through before deciding to download a free app, or why they decided to upgrade to pay for the app. In this book, we use the term ‘buy’ or ‘purchase’ to keep things simple. ‡

The process describes a rational step-by-step approach to decision making, and for many purchases it works well to explain the process. However, there are times when consumers don’t act in a rational way, may reconsider information received at one step, and so may repeat a stage or even start again, or are influenced by other internal and external factors (Erasmus et al., 2001). All of this needs to be considered by companies. We will discuss a few of the major influences in this chapter, but if you are pursuing a marketing career, you are encouraged to take a consumer behaviour course to find out more, along with other marketing courses that go into more detail. ‡

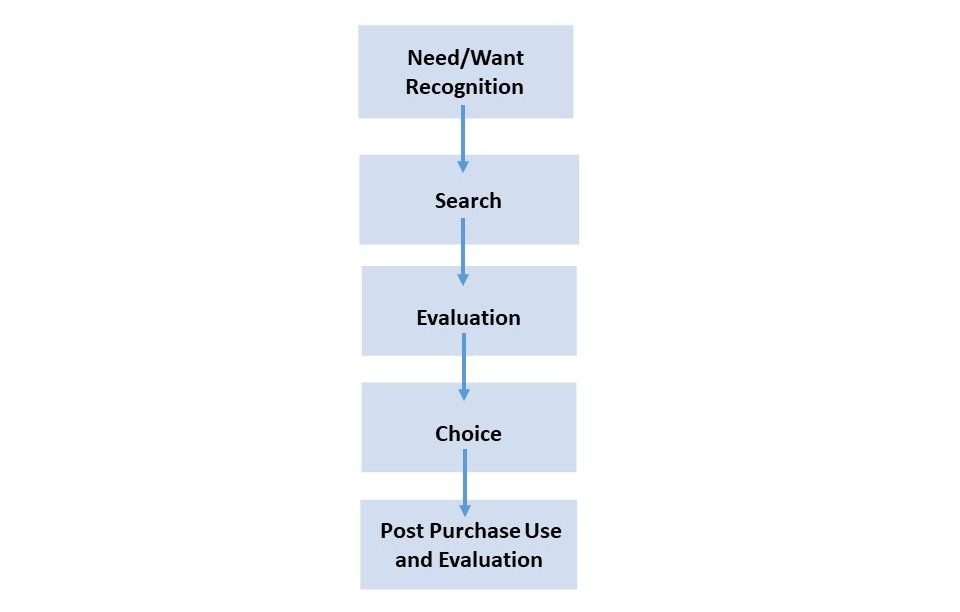

Figure 3.2 “Consumer Purchase Decision Process” shows the Consumer Decision Process with five stages: (1) Need recognition: realizing the need or want for something, (2) Search: searching for information, (3) Evaluation: evaluating different alternatives, (4) Choice: selecting a product and purchasing it, (5) Post Purchase Evaluation: using and evaluating the product (Engel et al., 1968). ‡

Joanne McNeish, Ryerson University CC BY-NC 4.0

To explore the five stages, let’s use an example of buying a backpack for travel. Note that some items that consumers purchase are needs (e.g. food) whereas other things are wants (a new generation smart phone or a new backpack). Often a ‘want’ reflects an underlying ‘need’. A new generation smart phone is the want but the underlying need is to be able to communicate. ‡

Stage 1: Need/Want Recognition

You plan to travel with a friend after you graduate. You want a bag that is easily carried and can be taken on the airplane with you so you don’t have to pay for checked luggage, but it needs to be big enough to hold enough clothes and other items for one month. You do not have a bag that is big or strong enough for a long trip. You realize that you may need to buy a new one and conclude that a backpack would be the ideal product. Notice that recognizing a need for a product or service is based on how you think about the problem. First you had to think about the task you wanted to accomplish. Your friend could be thinking about the same task and even the same criteria such as size and ease of carrying, may conclude that a suitcase on wheels is what they are looking for.‡ At the recognition stage, marketers make potential customers aware how their products and services add value and would help satisfy customer’s needs or wants. For example, seeing an advertisement for a Harvey’s plant-based burger may remind you that you haven’t had lunch yet. The company’s advertising helped you recognize a need. ‡

Stage 2: Search

Now, you will need to get information on different alternatives. Maybe you have owned several backpacks and know what you like and don’t like about them. There might be a particular brand that you’ve purchased in the past that you liked and want to purchase in the future. Any company wants to be in the position of being a preferred brand. If what you already know about backpacks doesn’t provide you with enough information, you’ll probably continue to gather information from various sources.

People may ask friends, and family about their experiences with products. They check online review site or related magazines or blogs. A review site offers product ratings, buying tips, and price information. Amazon.com also offers product reviews written by consumers. People prefer “independent” sources such as this when they are looking for product information. However, depending on the product being purchased they will consult non-neutral sources of information, for example such as Mountain Equipment Coop, a camping and sports retailer (MEC, n.d.). ‡

Stage 3: Evaluation

Obviously, there are hundreds of different backpacks. It’s not possible for you to examine all of them. In fact, too many choices can be so overwhelming that you might not buy anything at all. Consequently, you may use rules of thumb, which marketers call ‘choice heuristics’ that provide mental shortcuts in the decision-making process. You may also develop evaluative criteria to help you narrow down your choices. Backpacks that meet your initial criteria before the consideration will determine the set of brands you’ll consider for purchase.

Evaluative criteria are certain characteristics that are important to you such as the price of the backpack, the size, the number of compartments, and color. Some of these characteristics are more important than others. For example, the size of the backpack and the price might be more important to you than the color, unless, say, the color is hot pink and you hate pink. You must decide which criteria are most important and how well different alternatives meet the criteria.

Companies want to convince you that the evaluative criteria you are considering reflect the strengths of their products. For example, you might not have thought about the need for extra pockets or the type of zippers used for the backpack you want to buy. However, a backpack manufacturer such as Osprey will remind you about the various features of its backpacks through information on its website, tags attached to backpack and social media. That’s one feature they might use to differentiate their brands from others in a consumer’s mind. ‡

Stage 4: Choice

Once you have considered the alternatives, you decide which one to purchase. In addition to which backpack, you are probably also making other decisions at this stage, including where and how to purchase the backpack, and on what terms (e.g. debit card, credit card, Apple Pay). Maybe the backpack was cheaper at one store than another, but the salesperson there was rude. You may decide to order online from a retailer such as MEC because the backpack you selected was sold out in store, or you decided to buy it directly from the manufacturer because the selection of products was broader or an online intermediary such as Amazon because the price was cheaper than buying from the retailer or manufacturer. Or, maybe you object to Amazon’s business practices so you decide to buy from a business selling on Shopify, an e-commerce platform for online stores. ‡

Stage 5: Post Purchase Use and Evaluation

At this point in the process you decide whether the backpack you purchased is everything you wanted. Sometimes, after you purchase, you may experience post-purchase dissonance. Typically, dissonance occurs when a product or service does not meet all your expectations. Consumers are more likely to experience dissonance with products that are relatively expensive, or that are purchased infrequently. That’s why some retail stores have generous return policies. Even if the product was exactly what you wanted, you may wonder whether you should have waited to get a better price, purchased something else, or gathered more information first. One way in which companies handle the potential for cognitive dissonance is with guarantees. Osprey offers the following guarantee called the “All Mighty Guarantee, Any Reason, Any Product, Any Era.”

“Osprey will repair any damage or defect for any reason free of charge – whether it was purchased in 1974 or yesterday. If we are unable to perform a functional repair on your pack, we will happily replace it. We proudly stand behind this guarantee, so much so that it bears the signature of company founder and head designer, Mike Pfotenhauer” (Ospray, n.d.). ‡

Product Disposal

When the consumer decision model was first developed, there was little awareness of the risks to the earth’s climate, water and air from consumption behaviours. The production of products and services that flows from raw materials, to created product, to the point they are discarded as waste is called the linear economy. However, many consumers and companies are concerned about the amount of waste being created at every stage of the production and selling process. Companies use the term circular economy to describe a business production model that at every stage in the process: takes out waste and pollution; keep the products and materials they are made of in use for as long as possible; protects and regenerates natural systems (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, n.d.).

Using our example of buying a backpack for travel. When you returned, you went to work and put it in the back of a closet. Recently when cleaning out that closet, you came across it again. You don’t think you will use it again, but you don’t want to keep it. Under the linear economy model, you are responsible for disposing of it. You could throw it in the garbage but that would end up in landfill. You may try to sell it on e-Bay to get some of your money back. You could donate to a company such as Value Village where it will be resold to someone else. Another alternative would be to send it to TerraCycle. They claim to have a zero waste solution for recycling backpacks. You order a TerraCycle waste box, fill it and ship it back for them to recycle. DwellSmart is the place where the recycled products from TerraCycle are sold (DwellSmart, n.d.). ‡

Under the circular economy model, companies change the product so they help the consumer avoid creating more waste. Windex is a window glass cleaner. The only option used to be to buy it ready to use in a plastic bottle that you threw away when it was empty. Recently, the company produced the product as a concentrate to which you can add water and continue to use a reusable plastic bottle (Windex, n.d.). The consumer saves money because the concentrate is less expensive than the ready to use product and they avoid sending another plastic bottle to landfill. If possible, the ultimate goal of the circular economy is to avoid product purchase altogether. Instead of buying specialized window cleaning products that contain harmful chemicals, consumers can make their own. For example, window cleaner is easily made using vinegar and dish detergent (Schwartz & Vila, n.d.). ‡