Chapter 6 – Product Strategy & New Product Development: Creating Offerings

6.1 What Comprises an Offering?

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Distinguish between the three major components of an offering—product, price, and service.

- Explain, from both a product-dominant and a service-dominant approach, the mix of components that compose different types of offerings.

- Distinguish between technology platforms and product lines.

People buy things to fulfill needs. Offerings are products and services designed to deliver value to customers—either to fulfill their needs, satisfy their “wants,” or both. We discuss people’s needs in other chapters. In this chapter, we discuss how marketing fills those needs through the creation and delivery of offerings.

Product, Price, and Service

Most offerings consist of a product, or a tangible good people can buy, sell, and own. Purchasing a classic iPad, for example, will allow you to consume and store content. The amount of storage is an example of a feature, or characteristic of the offering. If your content consists of thousands of megabytes, then this feature delivers a benefit to you—the benefit of plenty of storage. However, the feature will only benefit you up to a point. For example, you won’t be willing to pay more for the 1 TB of storage if you only need 500 GB. When a certain level of a feature satisfies your need or want, then there is a benefit. Features, then, matter differently to different consumers based on each individual’s needs. Remember the value equation is different for every customer!

Value is equal to the benefit received from the purchase of a product minus the cost of purchasing that product. Therefore an offering also consists of a price, or the amount people pay to receive the offering’s benefits. The price paid can consist of a one-time payment, or it can consist of something more than that. Many consumers think of a product’s price as only the amount they paid; however, the true cost of owning an iPad, for example, is the cost of the device itself plus the cost of the music, videos, apps or other content downloaded onto it. The total cost of ownership (TCO), then, is the total amount someone pays to own, use, and eventually dispose of a product.

TCO is usually thought of as a concept that businesses use to compare offerings. However, consumers also use the concept. For example, suppose you are comparing two sweaters, one that can be hand-washed and one that must be dry-cleaned. The hand-washable sweater will cost you less to own in dollars but may cost more to own in terms of your time and effort. A smart consumer would take that into consideration. When we first introduced the personal value equation, we discussed effort as the time and energy spent making a purchase. A TCO approach, though, would also include the time and energy related to owning the product—in this case, the time and effort to hand wash the sweater.

A service is an action that provides a buyer with an intangible benefit. A haircut is a service. When you purchase a haircut, it’s not something you can hold, give to another person, or resell. “Pure” services are offerings that don’t have any tangible characteristics associated with them. Skydiving is an example of a pure service. You are left with nothing after the jump but the memory of it (unless you buy photos of the event). Yes, a plane is required, and it is certainly tangible. But it isn’t the product—the jump is. At times people use the term “product” to mean an offering that’s either tangible or intangible. Banks, for example, often advertise specific types of loans, or financial “products,” they offer consumers. Yet truly these products are financial services. The term “product” is frequently used to describe an offering of either type.

Many tangible products have an intangible service component attached to them, however. For example, Apple provides support for many of the computers as well as other devices. Could a company such as Apple back up the product, should something go wrong with it? As you can probably tell, a service does not have to be consumed to be an important aspect of an offering. Apple’s ability to provide good after-sales service in a timely fashion was an important selling characteristic of its products, even if buyers never had to use the service.

Sport Clips is a barbershop with a sports-bar atmosphere. The company’s slogan is “At Sport Clips, guys win.” So, although you may walk out of Sport Clips with the same haircut you could get from Pro Cuts, the experience you had getting it at Sport Clips was very different, which adds value for some buyers.

From the traditional product-dominant perspective of business, marketers consider products, services, and prices as three separate and distinguishable characteristics. To some extent, they are. Apple could, for example, add or strip out features from its products and not change its service policies or the equipment’s price. The product-dominant marketing perspective has its roots in the Industrial Revolution. During this era, businesspeople focused on the development of products that could be mass produced cheaply. In other words, firms became product-oriented, meaning that they believed the best way to capture market share was to create and manufacture better products at lower prices. Marketing remained oriented that way until after World War II.

The Service-Dominant Approach to Marketing

Who determines which products are better? Customers do, of course. Thus, taking a product-oriented approach can result in marketing professionals focusing too much on the product itself and not enough on the customer or service-related factors that customers want. Most customers will compare tangible products and the prices charged for them in conjunction with the services that come with them. In other words, the complete offering is the basis of comparison. So, although a buyer will compare the price of product A to the price of product B, in the end, the prices are compared in conjunction with the other features and services of the products. The dominance of any one of these dimensions is a function of the buyer’s needs.

The advantage of the service-dominant approach is that it integrates the product, price, and service dimensions of an offering. This integration helps marketers think more like their customers, which can help them add value to their firm’s products. In addition to the product itself, marketers should consider what services it takes for the customer to acquire their offerings (e.g., the need to learn about the product from a sales clerk), to enjoy them, and to dispose of them (e.g., someone to move the product out of the house and haul it away), because each of these activities create costs for their customers—either monetary costs or time and effort costs.

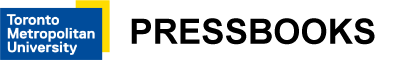

Critics of the service-dominant approach argue that the product-dominant approach also integrates services (though not price). The argument is that at the core of an offering is the product, such as an iPad, as illustrated in Figure 6.1. The physical product, in this case an iPad, is the core product. Surrounding it are services and accessories, called the augmented product, that support the core product. Thus, a core product is the central functional offering, but it may be augmented by various accessories or services, known as the augmented product. Together, these make up the complete product. One limitation of this approach has already been mentioned; price is left out. But for many “pure” products, this conceptualization can be helpful in bundling different augmentations for different markets.

This image is from Principles of Marketing by University of Minnesota and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Customers are now becoming more involved in the creation of benefits. Let’s look at the “pure” product, Campbell’s Cream of Chicken Soup. The consumer may prepare that can as a bowl of soup, but it could also be used as an ingredient in making King Ranch Chicken. For the customer, no benefit is experienced until the soup is eaten; thus, the consumer plays a part in the creation of the final “product” when the soup becomes an ingredient when they cook a King Ranch Chicken. Or suppose your school’s cafeteria made King Ranch Chicken for you to consume; in that case you both ate a product and consumed a service.

Some people argue that focusing too much on the customer can lead to too little product development or poor product development. These people believe that customers often have difficulty seeing how an innovative new technology can create benefits for them. Researchers and entrepreneurs frequently make many discoveries, and then products are created as a result of those discoveries. 3M’s Post-it Notes are an example. The adhesive that made it possible for Post-it Notes to stick and re-stick was created by a 3M scientist who was actually in the process of trying to make something else. Post-it Notes came later.

Product Levels and Product Lines

A product’s technology platform is the core technology on which it is built. Take for example, the iPad, which is based on iPadOS technology. In many cases, the development of a new offering is to take a technology platform and re-bundle its benefits in order to create a different version of an already-existing offering. For example, in addition to the iPad Classic, Apple offers the iPad Air, iPad Mini and iPad Pro. All are based on the same core technology.

In some instances, a new offering is based on a technology platform originally designed to solve different problems. For example, a number of products originally were designed to solve the problems facing NASA’s space-traveling astronauts. Later, that technology was used to develop new types of offerings. EQyss’s Micro Tek pet spray, which stops pets from scratching and biting themselves, is an example. The spray contains a trademarked formula developed by NASA to decontaminate astronauts after they return from space.

A technology platform isn’t limited to tangible products. Knowledge can be a type of technology platform in a pure services environment. For example, the “bioesthetic” treatment model was developed to help people who suffer from TMJ, a jaw disorder that makes chewing painful. A dentist can be trained on the bioesthetic technology platform and then provide services based on it. There are, however, other ways to treat TMJ that involve other platforms, or bases of knowledge and procedures, such as surgery.

Few firms survive by selling only one product. Most firms sell several offerings designed to work together to satisfy a broad range of customers’ needs and desires. A product line is group of related offerings. Product lines are created to make marketing strategies more efficient. Campbell’s condensed soups, for example, are basic soups sold in cans with red labels. But Campbell’s Chunky is a ready-to-eat soup sold in cans that are labeled differently. Most consumers expect there to be differences between Campbell’s red-label chicken soup and Chunky chicken soup, even though they are both made by the same company.

A product line can be broad, as in the case of Campbell’s condensed soup line, which consists of several dozen different flavors. Or, a product line can be narrow, as in the case of Apple’s MacBook line, which consists of only a few different laptop devices. How many offerings there are in a single product line—that is, whether the product line is broad or narrow—is called line depth. When new but similar products are added to the product line, it is called a line extension. If Apple introduces a new iPad to the iPad family, that would be a line extension. Companies can also offer many different product lines. Line breadth (or width) is a function of how many different, or distinct, product lines a company has. For example, Campbell’s has a Chunky soup line, condensed soup line, Kids’ soup line, Lower Sodium soup line, and a number of non-soup lines like Pace Picante sauces, Prego Italian sauces, and crackers. The entire assortment of products that a firm offers is called the product mix.

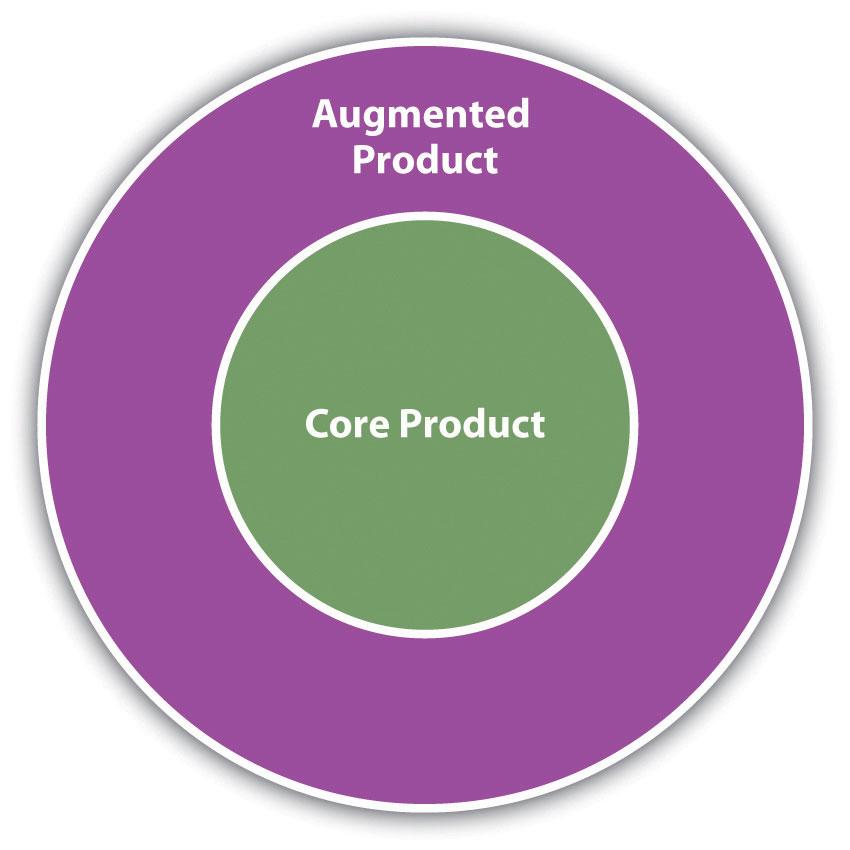

As Figure 6.2 “Product Levels” shows, there are four offering levels. Consider the Macbook Air. There is (1) the basic offering (the device itself), (2) the offering’s technology platform (the MacOS format or storage system used by the MacBook), (3) the product line to which the MacBook belongs (Apple’s MacBook line of laptops), and (4) the product category to which the offering belongs (laptops as opposed to desktops, for example).

Anthony Francescucci, Ryerson University CC BY-NC 4.0

So how does a technology platform become a new product or service or line of new products and services? Later in this chapter, we take a closer look at how companies design and develop new offerings.