Chapter 9 – Place (Distribution) Strategy

9.1 Marketing Channels and Channel Partners

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Explain why marketing channel decisions can result in the success or failure of products.

- Understand how supply chains differ from marketing channels.

- Describe the different types of companys that work together as channel partners and what each does.

Today, marketing channel decisions are as important as the decisions companies make about the features and prices of their products (Littleson, 2007). Consumers have become more demanding and have more choices available to them, including buying from other people rather than companies. For example, the growth of peer-to-peer selling on platforms such as Poshmark and Kijiji appeal to a group of consumers who want to pay a lower price for a product, don’t want a retail experience and don’t require products that are newly manufactured. Some consumers even consider buying gently used products a way to live a more environmentally sustainable life.‡

This chapter focused on the process that creates the product from raw materials to finished product sold direct to the consumer by the company or indirectly through retail intermediaries. Channel partners are companies that other companies work with in order to promote or sell their product. In other words, the product travels through a marketing channel to reach the final user, and all channel partners are responsible (in part) from the product’s success in the marketplace. Companies strive to choose not the most appropriate marketing channels, and the most successful channel partners. A manufacturer who partners with a strong channel partner such as Walmart can promote and sell millions of product units they might otherwise not sell, which helps them create more profit. In turn, Walmart wants to work with strong channel partners it can depend on. This way, Walmart can continuously provide its customers with great products a low price. For each party mentioned above, a weak channel partner can be a liability.

The simplest marketing channel consists of just two parties, a producer and a consumer. First Choice Haircutters is one example. When you get a haircut, it is done by the hairstylist only for you. No one else owns, handles, or remarkets the haircut to you before you get it. However, many other products and services pass through multiple companies before they get to you. These companies are called intermediaries.

Companies partner with intermediaries not because they necessarily want to (ideally, they could sell their products straight to users through paper or digital catalogues), but because the intermediaries can help them sell products more efficiently than they could working alone. In other words, they have some capabilities that the producer needs. These capabilities may be: contact with many customers (or the right customers), marketing expertise, shipping and handling capabilities, and the ability to lend the producer credit. There are four forms of utility, or value, that channels offer. These are time, form, place, and ownership.

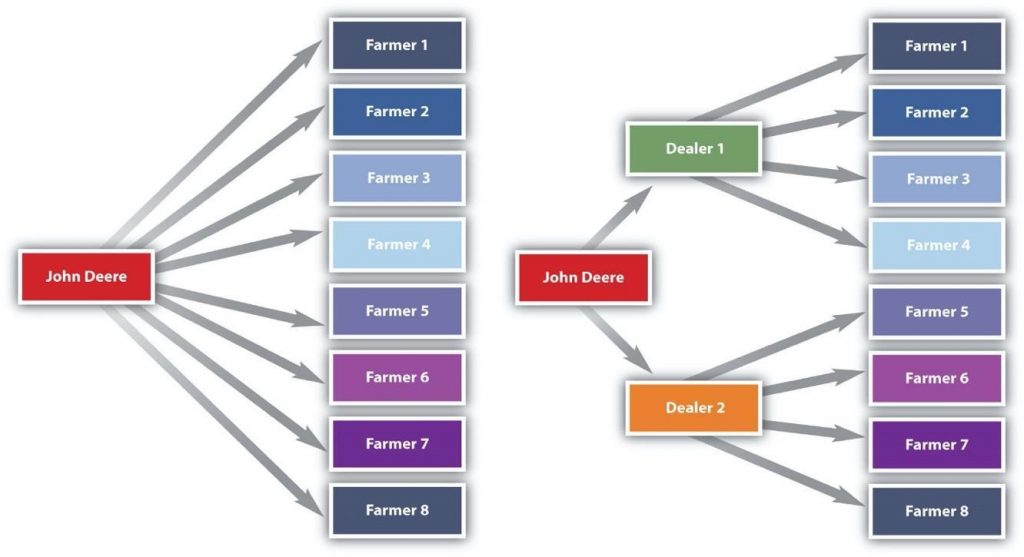

Intermediaries also create efficiencies by streamlining the number of transactions an company must make, each of which takes time and costs money to conduct. As Figure 9.1 “Using Intermediaries to Streamline the Number of Transactions” shows, by selling the tractors it makes through local farm machinery dealers, the farm machinery manufacturer John Deere can streamline the number of transactions it makes from eight to just two.

This image is from Principles of Marketing by University of Minnesota and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The marketing environment is always changing, so what was an appropriate channel or channel partner yesterday might not make the right one for today. Changes in technology, production techniques, and your customer’s needs mean you have to continually reevaluate your marketing channels and the channel partners you ally yourself with. Moreover, when you create a new product, you can’t assume the channels that were used in the past are the best ones (Lancaster & Withey, 2007). A different channel or channel partner might be better.

In addition to making changes to its products and services or introducing new ones, creating and maintaining a sustainable competitive advantage, a company must therefore monitor changes in distribution methods. One of the most impactful changes to the distribution of information was the internet. From 1768 to 2000, consumers and libraries considered printed copies of Encyclopedia Britannica an essential research tool and it had few competitors. In 1993, Microsoft introduced a digital encyclopedia called Encarta. It was sold first on CD, and then via online subscription that allowed for continuous updating for a low subscription price. In 1994, along with producing the print version, Encyclopedia Britannica was released on CD and then in 1999, online (Britannica, n.d.). By 2009, Microsoft made the decision to stop selling Encarta. Why? The strong brand name recognition of Encyclopedia Britannica among librarians, free online search and Wikipedia, a free online encyclopedia. In 2012, Encyclopedia Britannica stopped producing printed copies and went ‘digital only’ to better manage its costs and has been profitable since 2003 (Frenkel, 2012). Wikipedia is a non-profit company. It operates as a free service, supported by donations from users and a few large corporations (Dewey, 2015).‡

Marketing Channels versus Supply Chains

In the past few decades, companies have begun taking a more holistic look at their marketing channels. Instead of looking at only the companies that sell and promote their products, they have begun looking at all companies that figure into any part of the process of producing, promoting, and delivering an offering to its user. All these companies are considered part of the supply chain.

For instance, the supply chain includes producers of the raw materials that go into a product. The supply chain of a food product extends back through the distributors all the way to the farmers who grew the ingredients and the companies from which the farmers purchased the seeds, fertilizer, or animals. A product’s supply chain also includes transportation companies such as railroads or trucks that help move the product or companies that build websites. If a software maker hires a company in India to help it write code for their website, the Indian company is part of the partner’s supply chain. These types of companies aren’t considered channel partners because it’s not their job to actively sell the products being produced. Nonetheless, they all contribute to a product’s success or failure.

Companies are constantly monitoring and improving the efficiency of their supply chains in a process called supply chain management. Supply chain management is challenging, particularly if the company operates across a country’s borders and/or if an unforeseeable global event occurs. One salient example is the COVID-19 pandemic, which demonstrated the risks of supply chain management (BDC, n.d.). During the pandemic, companies faced various supply chain management hurdles including delays in their own production facilities (e.g., factories being closed from outbreaks of the virus), reduction in the number of truck drivers that could deliver their products to retailers, and unanticipated spikes in demand from consumers. For example, toilet paper shortages at retail stores were a surprise to many. In contrast to the spike in increased demand from consumers, some companies were also surprised by the unexpected lower demand from businesses. For example, the pandemic led to many restaurants, stores, and public washrooms being closed, resulting in lower sales for toilet paper specifically produced for businesses (Wieczner, 2020). Within a few weeks, companies adapted to the new demand structure from the market and made changes in their supply chain to meet this demand structure. They started to slowly divert their production from business-use toilet paper to consumer-use ones, and began sending their trucks to make deliveries to grocery warehouses rather than retail and restaurant locations. ‡

Types of Channel Partners

Let’s look at the basic types of channel partners. The two types you hear about most frequently are wholesalers and retailers. Note that in recent years, the lines between wholesalers, retailers, and producers have begun to blur. Samsung is a manufacturer of electronics but in 2012 opened its first retail store in Canada and in 2020 its seventh store in Quebec (Patterson 2020), although it had operated retail stores in the U.S. for eight years previously. Many large retailers produce and/or sell their own store brands and may even sell them to other retailers. Many producers have outsourced their manufacturing, and although they still call themselves manufacturers, they act more like wholesalers. By adding a new distribution channel, companies are hoping to improve the profitability of their whole operation.‡

Wholesalers

Wholesalers obtain large quantities of products from producers, store them, and break them down into cases and other smaller units that are more convenient for retailers to buy, a process called “breaking bulk.” Wholesalers get their name from the fact that they resell goods “whole” to other companies without transforming the goods. If you manage a small electronics store, you probably don’t want to purchase a full truckload of computer tablets. Instead, you probably want to buy a smaller assortment of brands. Via wholesalers, you can get an assortment of brands in smaller quantities that suits your available retail space. Some wholesalers carry a wide range of products while others carry a narrow range. Most wholesalers “take title” of goods, or own them, until these products are purchased by other sellers. As a result, many wholesalers often assume a great deal of risk on the part of companies further down the marketing channel. For example, if the shipment of tablets are stolen during their transport, are damaged, or become outdated because a new model has been released, the wholesaler suffers the loss, and not the producer or the retailer.

There are many types of wholesalers. The three basic types of wholesalers are merchant wholesalers, brokers, and manufacturers’ agents, each of which we discuss next.

Merchant Wholesalers

Merchant wholesalers are wholesalers that take title to the goods and therefore have more financial risk than other wholesalers. They are also sometimes referred to as distributors, dealers, and jobbers. The category includes both full-service wholesalers and limited-service wholesalers. Full-service wholesalers perform a broad range of services for their customers, such as stocking inventories, operating warehouses, supplying credit to buyers, employing salespeople to assist customers, and delivering goods to customers. Maurice Sporting Goods is a large North American full-service wholesaler of hunting and fishing equipment. The company’s services include helping customers figure out which products to stock, how to price them, and how to display them.

Limited-Service Wholesalers

Limited-service wholesalers offer fewer services to their customers, but at lower prices. They might not offer delivery services, extend their customers’ credit, or have sales forces that actively call sellers. Cash-and-carry wholesalers are an example. Small retailers often buy from cash-and-carry wholesalers to keep their prices as low as big retailers that get large discounts because of the huge volumes of goods they buy.

Drop Shippers

Drop shippers are another type of limited-service wholesaler. Although drop shippers take title to the goods, they don’t have legal possession. In this way they avoid, the financial risks of other wholesalers. They earn a commission by finding sellers and passing their orders along to producers, who then ship them directly to the sellers. Mail-order wholesalers sell their products using catalogs instead of sales forces, and then ship the products to buyers. Truck jobbers (or truck wholesalers) actually store products, which are often highly perishable (e.g., fresh fish), on their trucks. The trucks make the rounds to customers, who inspect and select the products they want straight off the trucks.

Rack Jobbers

Rack jobbers sell specialty products, such as books, hosiery, and magazines that they display on their own racks in stores. Rack jobbers retain the title to the goods while the merchandise is in the stores for sale. Periodically, they take count of what’s been sold off their racks and then bill the stores for those items.

Brokers and Agents

Brokers or agents don’t purchase or take title to the products they sell. Their role is limited to negotiating sales contracts for producers and are paid a commission for what they sell. Clothing, furniture, food and commodities (e.g. lumber and steel) are often sold by brokers. Brokers and agents are assigned to geographical territories by the producers with whom they work. Because they have excellent industry contacts, brokers and agents may be “go-to” resources for companies trying to buy and sell products.

Consumers may encounter agents or brokers when buying or selling a property. A real estate agent represents either the buyer or the seller and charges a commission on the sale. The homeowner contacts a listing agent. The buyer may encounter an agent during ‘open houses’ or contact an agent to show them the available inventory of properties that meets their specifications. If there is a house that the buyer wants to purchase, the agent calls the listing agent and a price is negotiated between the parties. Many agents work for brokers, who promote the company’s services and handle the legal requirements. However, like many services today, consumers may prefer to sell or buy a house directly from the owner to avoid the agent’s commission (Mercadante, 2021).

Manufacturers’ Sales Offices

Manufacturers’ Sales Offices or Branches are selling units that work directly for manufacturers. These are found in business-to-business settings. For example, Konica-Minolta Business Systems (KMBS) has a system of sales branches that sell KMBS printers and copiers directly to companies that need them.

Retailers

Retailers buy products from wholesalers, agents, or distributors and then sell them to consumers. Retailers vary by the types of products they sell, their sizes, the prices they charge, the level of service they provide consumers, and the convenience or speed they offer. You are familiar with many of these types of retailers because you have purchased products from them. We mentioned Nike and Apple as examples of companies that make and sell products directly to consumers as well as indirectly through retail stores. Nike and Apple contract manufacturing to other companies. They may design the products, but they actually buy the finished goods from others.

Grocery Stores

Grocery stores are self-service retailers that provide a full range of food products to consumers, as well as some household products. Grocery stores can be high, medium, or low range in terms of the prices they charge and the service and variety of products they offer. Whole Foods and Fortino’s are grocers that offer a wide variety of products, generally at higher prices. Midrange grocery stores include stores such as Metro, Sobeys, Lobaws and Real Canadian Superstores. No Frills, Budget Foods and Shop ’n Save are examples of grocery stores with low prices and a limited selection of products and services. Drugstores such as Shoppers Drugmart and Rexall specialize in selling over-the-counter medications, prescriptions, and health and beauty products and some of the larger stores offer grocery products as well.

Convenience Stores

Convenience stores are miniature supermarkets. Many of them sell gasoline and are open twenty-four hours a day. Often they are located on corners, making it easy and fast for consumers to get in and out. Some of these stores contain fast-food franchises such as Tim Hortons. Consumers pay for the convenience in the form of higher markups on products. In Europe, you will find convenience stores that offer fresh meat and produce.

Specialty Stores

Specialty stores sell a certain type of product, but they usually carry a deep line of it. Peoples and Ben Moss, which sells jewelry, and Williams-Sonoma, which sells an array of kitchen and cooking-related products, are examples of specialty stores. The employees who work in specialty stores are usually knowledgeable and often provide customers with a high level of service. Specialty stores vary by size. Many are small. However, in recent years, giant specialty stores called category killers have emerged. A category killer sells a high volume of a particular type of product and, in doing so, dominates the competition, or the “category.” PetSmart is a category killer in the retail pet-products market. Best Buy and Amazon are category killers in the electronics market.

Department Stores

Department stores, by contrast, carry a wide variety of household and personal types of merchandise such as clothing and jewelry. Many are chain stores. The prices department stores charge range widely, as does the level of service shoppers receive. For example, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Nordstrom sell expensive products and offer extensive personal service to customers. For the most part, The Bay charges midrange prices along with that level of customer service. Walmart is a discount department store that sells the cheapest goods and provides little customer service (note that when Walmart sells groceries along with other merchandise it is called a superstore). However, the retail landscape is constantly shifting and department stores have taken action to remain competitive. The retail brands Saks Off 5th and Nordstrom Rack were launched to sell discounted inventory from their main stores and to offer a low cost brand produced for the store. The Bay has gone a different way and has increased its offering of expensive designer brands along with producing and selling its own branded merchandise.

Superstores

Superstores are larger versions of regular priced or discount department stores that carry a broad array of general merchandise as well as groceries. Banks, hair and nail salons, and restaurants such as Starbucks are often located within these stores for the convenience of shoppers. You have probably shopped at Walmart or Real Canadian Superstore with offerings such as these. Superstores may also be referred to as hypermarkets and supercenters.

Warehouse Clubs

Warehouse clubs are supercenters that sell products at a discount. They require people who shop with them to become members by paying an annual fee. Costco is one example.

Off-Price Retailers

Off-price retailers are stores that sell a variety of discount merchandise that consists of seconds, overruns, and the previous season’s stock other stores have liquidated. Winners, Marshalls, Home Sense, and dollar stores are off-price retailers (Patterson, 2018a).

Outlet Stores

Outlet stores are discount retailers that operate under the brand name of a single manufacturer, selling products that couldn’t be sold through normal retail channels due to mistakes made in manufacturing or overstocks in inventory. Often located in rural areas but along major highways, these stores had lower overhead than similar stores in big cities due to lower rent and lower employee salaries.

Online Retailers

Online retailers can fit into any of the previous categories and most brick and mortar stores have an online store. There are few pure-play, or online only stores. One example is Wayfair. Companies such as Amazon which began as an online only retailer, have set up or acquired bricks and mortars stores in order to increase sales (Petro, 2021).

Used or Thrift Retailers

Used or thrift retailers are retailers that sell used products. With the advent of peer-to-peer online selling sites such as Kijiji and Craigslist, traditional used stores have a smaller share of the overall market. One large used retailer, Value Village has adapted its business model of selling used items to include supporting local nonprofit companies and creating recycling and reuse program to keep items out of landfill (Value Village, n.d.).‡

Pop-Up Stores

Pop-up stores are small temporary stores. They can be kiosks or temporarily occupy unused retail space. The goal is to create excitement and “buzz” for a new retailer to test a concept or an existing retailer to encourage new customers to visit their regular stores. They can be a way for malls to fill empty stores. Pop-up stores can also be used around holidays or seasonal products, such as a costume store before Halloween.

Not all retailing goes on in stores. In Canada, non-store retailing or direct marketing, retailing not conducted in stores, is growing although still relatively small in overall revenue (0.05% of total retail trade, est. 20% growth rate) compared to brick and mortar retailing (3.3% growth rate) (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2021a). Non-store retailers use a variety of methods including broadcasting infomercials, broadcasting and publishing direct-response advertising, publishing traditional and electronic catalogues, door-to-door solicitation, in-home demonstration, temporary displaying of merchandise (temporary stands or stalls), distribution by vending machines, and selling ‘exclusively online’ to reach their customers and sell their merchandise (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2021b). Companies that engage in direct marketing communicate directly with consumers and want them to contact the companies directly to buy products.