The Underground Railroad

“Fleeing Girl of Fifteen,” in Male Attire

PROFESSORS H. AND T. OFFER THEIR SERVICES—CAPTAINS B. ALSO ARE ENLISTED—SLAVE-TRADER GRASPING TIGHTLY HIS PREY, BUT SHE IS RESCUED—LONG CONFLICT, BUT GREAT TRIUMPH—ARRIVAL ON THANKSGIVING DAY, NOV. 25, 1855.

It was the business of the Vigilance Committee, as it was clearly understood by the friends of the Slave, to assist all needy fugitives, who might in any way manage to reach Philadelphia, but, for various reasons, not to send agents South to incite slaves to run away, or to assist them in so doing. Sometimes, however, this rule could not altogether be conformed to. Cases, in some instances, would appeal so loudly and forcibly to humanity, civilization, and Christianity, that it would really seem as if the very stones would cry out, unless something was done. As an illustration of this point, the story of the young girl, which is now to be related, will afford the most striking proof. At the same time it may be seen how much anxiety, care, hazard, delay and material aid, were required in order to effect the deliverance of some who were in close places, and difficult of access. It will be necessary to present a considerable amount of correspondence in this case, to bring to light the hidden mysteries of this narrative. The first letter, in explanation, is the following:

LETTER FROM J. BIGELOW, ESQ.

WASHINGTON, D.C., June 27, 1854.

MR. WM. STILL—Dear Sir:—I have to thank you for the prompt answer you had the kindness to give to my note of 22d inst. Having found a correspondence so quick and easy, and withal so very flattering, I address you again more fully.

The liberal appropriation for transportation has been made chiefly on account of a female child of ten or eleven years old, for whose purchase I have been authorized to offer $700 (refused), and for whose sister I have paid $1,600, and some $1,000 for their mother, &c.

This child sleeps in the same apartment with its master and mistress, which adds to the difficulty of removal. She is some ten or twelve miles from the city, so that really the chief hazard will be in bringing her safely to town, and in secreting her until a few days of storm shall have abated. All this, I think, is now provided for with entire safety.

The child has two cousins in the immediate vicinity; a young man of some twenty-two years of age, and his sister, of perhaps seventeen—both Slaves, but bright and clear-headed as anybody. The young man I have seen often—the services of both seem indispensable to the main object suggested; but having once rendered the service, they cannot, and ought not return to Slavery. They look for freedom as the reward of what they shall now do.

Out of the $300, cheerfully offered for the whole enterprise, I must pay some reasonable sum for transportation to the city and sustenance while here. It cannot be much; for the balance, I shall give a draft, which will be promptly paid on their arrival in New York.

If I have been understood to offer the whole $300, it shall be paid, though I have meant as above stated. Among the various ways that have been suggested, has been that of taking all of them into the cars here; that, I think, will be found impracticable. I find so much vigilance at the depot, that I would not deem it safe, though, in any kind of carriage they might leave in safety at any time.

All the rest I leave to the experience and sagacity of the gentleman who maps out the enterprise.

Now I will thank you to reply to this and let me know that it reaches you in safety, and is not put in a careless place, whereby I may be endangered; and state also, whether all my propositions are understood and acceptable, and whether, (pretty quickly after I shall inform you that all things are ready), the gentleman will make his appearance?

I live alone. My office and bed-room, &c., are at the corner of E. and 7th streets, opposite the east end of the General Post Office, where any one may call upon me.

It would, of course, be imprudent, that this letter, or any other written particulars, be in his pockets for fear of accident.

Yours very respectfully,

J. BIGELOW.

While this letter clearly brought to light the situation of things, its author, however, had scarcely begun to conceive of the numberless difficulties which stood in the way of success before the work could be accomplished. The information which Mr. Bigelow’s letter contained of the painful situation of this young girl was submitted to different parties who could be trusted, with a view of finding a person who might possess sufficient courage to undertake to bring her away. Amongst those consulted were two or three captains who had on former occasions done good service in the cause. One of these captains was known in Underground Rail-Road circles as the “powder boy.”[1] He was willing to undertake the work, and immediately concluded to make a visit to Washington, to see how the “land lay.” Accordingly in company with another Underground Rail Road captain, he reported himself one day to Mr. Bigelow with as much assurance as if he were on an errand for an office under the government. The impression made on Mr. Bigelow’s mind may be seen from the following letter; it may also be seen that he was fully alive to the necessity of precautionary measures.

SECOND LETTER FROM LAWYER BIGELOW.

WASHINGTON, D.C., September 9th, 1855.

MR. WM. STILL, DEAR SIR:—I strongly hope the little matter of business so long pending and about which I have written you so many times, will take a move now. I have the promise that the merchandize shall be delivered in this city to-night. Like so many other promises, this also may prove a failure, though I have reason to believe that it will not. I shall, however, know before I mail this note. In case the goods arrive here I shall hope to see your long-talked of “Professional gentleman” in Washington, as soon as possible. He will find me by the enclosed card, which shall be a satisfactory introduction for him. You have never given me his name, nor am I anxious to know it. But on a pleasant visit made last fall to friend Wm. Wright, in Adams Co., I suppose I accidentally learned it to be a certain Dr. H——. Well, let him come.

I had an interesting call a week ago from two gentlemen, masters of vessels, andbrothers, one of whom, I understand, you know as the “powder boy.” I had a little light freight for them; but not finding enough other freight to ballast their craft, they went down the river looking for wheat, and promising to return soon. I hope to see them often.

I hope this may find you returned from your northern trip,[2]as your time proposed was out two or three days ago.

I hope if the whole particulars of Jane Johnson’s case[3]are printed, you will send me the copy as proposed.

I forwarded some of her things to Boston a few days ago, and had I known its importance in court, I could have sent you one or two witnesses who would prove that her freedom was intended by her before she left Washington, and that a man wasengagedhere to go on to Philadelphia the same day with her to give notice there of her case, though I think he failed to do so. It was beyond all question her purpose,before leaving Washington and provable too, that if Wheeler should make her a free woman by taking her to a free state “to use it rather.”

Tuesday, 11th September. The attempt was made on Sunday to forward the merchandize, but failed through no fault of any of the parties that I now know of. It will be repeated soon, and you shall know the result.

“Whorra for Judge Kane.” I feel so indignant at the man, that it is not easy to write the foregoing sentence, and yet who is helping our cause like Kane and Douglas, not forgetting Stringfellow. I hope soon to know that this reaches you in safety.

It often happens that light freight would be offered to Captain B., but the owners cannot by possibilityadvancethe amount of freight. I wish it were possible in some such extreme cases, that after advancingall they have, some public fund should be found to pay the balance or at least lend it.

[I wish here to caution you against the supposition that I would do any act, or say a word towards helping servants to escape. Although I hate slavery so much, I keep my hands clear of any such wicked or illegal act.]

Yours, very truly,

J.B.

Will you recollect, hereafter, that in any of my future letters, in which I may use [] whatever words may be within the brackets are intended to have no signification whatever to you, only to blind the eyes of the uninitiated. You will find an example at the close of my letter.

Up to this time the chances seemed favorable of procuring the ready services of either of the above mentioned captains who visited Lawyer Bigelow for the removal of the merchandize to Philadelphia, providing the shipping master could have it in readiness to suit their convenience. But as these captains had a number of engagements at Richmond, Petersburg, &c., it was not deemed altogether safe to rely upon either of them, consequently in order to be prepared in case of an emergency, the matter was laid before two professional gentlemen who were each occupying chairs in one of the medical colleges of Philadelphia. They were known to be true friends of the slave, and had possessed withal some experience in Underground Rail Road matters. Either of these professors was willing to undertake the operation, provided arrangements could be completed in time to be carried out during the vacation. In this hopeful, although painfully indefinite position the matter remained for more than a year; but the correspondence and anxiety increased, and with them disappointments and difficulties multiplied. The hope of Freedom, however, buoyed up the heart of the young slave girl during the long months of anxious waiting and daily expectation for the hour of deliverance to come. Equally true and faithful also did Mr. Bigelow prove to the last; but at times he had some painfully dark seasons to encounter, as may be seen from the subjoined letter:

WASHINGTON, D.C., October 6th, 1855.

MR. STILL, DEAR SIR:—I regret exceedingly to learn by your favor of 4th instant, that all things are not ready. Although I cannot speak of any immediate and positive danger. [Yet it is well known that the city is full of incendiaries.]

Perhaps you are aware that any colored citizen is liable at any hour of day or night without any show of authority to have his house ransacked by constables, and if others do it and commit the most outrageous depredations none but white witnesses can convict them. Such outrages are always common here, and no kind of property exposed to colored protection only, can be considered safe. [I don’t say that much liberty should not be given to constables on account of numerous runaways, but it don’t always work for good.] Before advertising they go round and offer rewards to sharp colored men of perhaps one or two hundred dollars, to betray runaways, and having discovered their hiding-place, seize them and then cheat their informers out of the money.

[Although a law-abiding man,] I am anxious in this case of innocence to raise no conflict or suspicion. [Be sure that the manumission is full and legal.] And as I am powerless without your aid, I pray you don’t lose a moment in giving me relief. The idea of waiting yet for weeks seems dreadful; do reduce it to days if possible, and give me notice of the earliest possible time.

The property is not yet advertised, but will be, [and if we delay too long, may be sold and lost.]

It was a great misunderstanding, though not your fault, that so much delay would be necessary. [I repeat again that I must have the thing done legally, therefore, please get a good lawyer to draw up the deed of manumission.]

Yours Truly,

J. BIGELOW.

Great was the anxiety felt in Washington. It is certainly not too much to say, that an equal amount of anxiety existed in Philadelphia respecting the safety of the merchandise. At this juncture Mr. Bigelow had come to the conclusion that it was no longer safe to write over his own name, but that he would do well to henceforth adopt the name of the renowned Quaker, Wm. Penn, (he was worthy of it) as in the case of the following letter.

WASHINGTON, D.C., November 10th, 1855.

DEAR SIR:—Doctor T. presented my card last night about half past eight which I instantly recognized. I, however, soon became suspicious, and afterwards confounded, to find the doctor using your name and the well known names of Mr. McK. and Mr. W. and yet, neither he nor I, could conjecture the object of his visit.

The doctor is agreeable and sensible, and doubtless a true-hearted man. He seemed to see the whole matter as I did, and was embarrassed. He had nothing to propose, no information to give of the “P. Boy,” or of any substitute, and seemed to want no particular information from me concerning my anxieties and perils, though I stated them to him, but found him as powerless as myself to give me relief. I had an agreeable interview with the doctor till after ten, when he left, intending to take the cars at six, as I suppose he did do, this morning.

This morning after eight, I got your letter of the 9th, but it gives me but little enlightenment or satisfaction. You simply say that the doctor is a true man, which I cannot doubt, that you thought it best we should have an interview, and that you supposed I would meet the expenses. You informed me also that the “P. Boy” left for Richmond, on Friday, the 2d, to be gone the length of time named in your last, I must infer that to be ten days though in your last you assured me that the “P. Boy” would certainly start for this place (not Richmond) in two or three days, though the difficulty about freight might cause delay, and the whole enterprise might not be accomplished under ten days, &c., &c. That time having elapsed and I having agreed to an extra fifty dollars to ensure promptness. I have scarcely left my office since, except for my hasty meals, awaiting his arrival. You now inform me he has gone to Richmond, to be gone ten days, which will expire tomorrow, but you do not say he will return here or to Phila, or where, at the expiration of that time, and Dr. T. could tell me nothing whatever about him. Had he been able to tell me that this best plan, which I have so long rested upon, would fail, or was abandoned, I could then understand it, but he says no such thing, and you say, as you have twice before said, “ten days more.”

Now, my dear sir, after this recapitulation, can you not see that I have reason for great embarrassment? I have given assurances, both here and in New York, founded on your assurances to me, and caused my friends in the latter place great anxiety, so much that I have had no way to explain my own letters but by sending your last two to Mr. Tappan.

I cannot doubt, I do not, but that you wish to help me, and the cause too, for which both of us have made many and large sacrifices with no hope of reward in this world. If in this case I have been very urgent since September Dr. T. can give you some of my reasons, they have not been selfish.

The whole matter is in a nutshell. Can I, in your opinion, depend on the “P. Boy,” and when?

If he promises to come here next trip, will he come, or go to Richmond? This I think is the best way. Can I depend on it?

Dr. T. promised to write me some explanation and give some advice, and at first I thought to await his letter, but on second thought concluded to tell you how I feel, as I have done.

Will you answer my questions with some explicitness, and without delay?

I forgot to inquire of Dr. T. who is the head of your Vigilance Committee, whom I may address concerning other and further operations?

Yours very truly,

WM. PENN.

P.S. I ought to say, that I have no doubt but there were good reasons for the P. Boy’s going to Richmond instead of W.; but what can they be?

Whilst there are a score of other interesting letters, bearing on this case, the above must suffice, to give at least, an idea of the perplexities and dangers attending its early history. Having accomplished this end, a more encouraging and pleasant phase of the transaction may now be introduced. Here the difficulties, at least very many of them, vanish, yet in one respect, the danger became most imminent. The following letter shows that the girl had been successfully rescued from her master, and that a reward of five hundred dollars had been offered for her.

WASHINGTON, D.C., October 12, 1855.

MR. WM. STILL:—AS YOU PICK UP ALL THE NEWS THAT IS STIRRING, I CONTRIBUTE A FEW SCRAPS TO YOUR STOCK, GOING TO SHOW THAT THE POOR SLAVE-HOLDERS HAVE THEIR TROUBLES AS WELL AS OTHER PEOPLE.

FOUR HEAVY LOSSES ON ONE SMALL SCRAP CUT FROM A SINGLE NUMBER OF THE “SUN!” HOW VEXATIOUS! HOW PROVOKING! ON THE OTHER HAND, THINK OF THE POOR, TIMID, BREATHLESS, FLYING CHILD OF FIFTEEN!FIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS REWARD!OH, FOR SUCCOR! TO WHOM IN ALL THIS WIDE LAND OF FREEDOM SHALL SHE FLEE AND FIND SAFETY? ALAS!—ALAS!—THE LAW POINTS TO NO ONE!

IS SHE STILL RUNNING WITH BLEEDING FEET?[4]OR HIDES SHE IN SOME COLD CAVE, TO REST AND STARVE? “$500 REWARD.” YOURS, FOR THE WEAK AND THE POOR.PERISHTHE REWARD.

J.B.

Having thus succeeded in getting possession of, and secreting this fleeing child of fifteen, as best they could, in Washington, all concerned were compelled to “possess their souls in patience,” until the storm had passed. Meanwhile, the “child of fifteen” was christened “Joe Wright,” and dressed in male attire to prepare for traveling as a lad. As no opportunity had hitherto presented itself, whereby to prepare the “package” for shipment, from Washington, neither the “powder boy” nor Dr. T.[5] was prepared to attend to the removal, at this critical moment. The emergency of the case, however, cried loudly for aid. The other professional gentleman (Dr. H.), was now appealed to, but his engagements in the college forbade his absence before about Thanksgiving day, which was then six weeks off. This fact was communicated to Washington, and it being the only resource left, the time named was necessarily acquiesced in. In the interim, “Joe” was to perfect herself in the art of wearing pantaloons, and all other male rig. Soon the days and weeks slid by, although at first the time for waiting seemed long, when, according to promise, Dr. H. was in Washington, with his horse and buggy prepared for duty. The impressions made by Dr. H., on William Penn’s mind, at his first interview, will doubtless be interesting to all concerned, as may be seen in the following letter:

WASHINGTON, D.C., November 26, 1855.

MY DEAR SIR:—A recent letter from my friend, probably has led you to expect this from me. He was delighted to receive yours of the 23d, stating that the boy was all right. He found the “Prof. gentleman” a perfect gentleman; cool, quiet, thoughtful, and perfectly competent to execute his undertaking. At the first three minutes of their interview, he felt assured that all would be right. He, and all concerned, give you and that gentleman sincere thanks for what you have done. May the blessings of Him, who cares for the poor, be on your heads.

The especial object of this, is to inform you that there is a half dozen or so of packages here, pressing for transportation; twice or thrice that number are also pressing, but less so than the others. Their aggregate means will average, say, $10 each; besides these, we know of a few, say three or four, able and smart, but utterly destitute, and kept so purposely by their oppressors. For all these, we feel deeply interested; $10 each would not be enough for the “powder boy.” Is there any fund from which a pittance could be spared to help these poor creatures? I don’t doubt but that they would honestly repay a small loan as soon as they could earn it. I know full well, that if you begin with such cases, there is no boundary at which you can stop. For years, one half at least, of my friend’s time here has been gratuitously given to cases of distress among this class. He never expects or desires to do less; he literally has the poor always with him. He knows that it is so with you also, therefore, he only states the case, being especially anxious for at least those to whom I have referred.

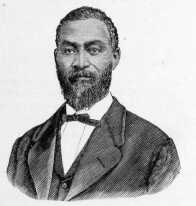

MARIA WEEMS ESCAPING IN MALE ATTIRE

I think a small lot of hard coal might always be sold here from the vessel at a profit. Would not a like lot of Cumberland coal always sell in Philadelphia?

My friend would be very glad to see the powder boy here again, and if he brings coal, there are those here, who would try to help him sell.

Reply to your regular correspondent as usual.

WM. PENN.

By the presence of the Dr., confidence having been reassured that all would be right, as well as by the “inner light,” William Penn experienced a great sense of relief. Everything having been duly arranged, the doctor’s horse and carriage stood waiting before the White House (William Penn preferred this place as a starting point, rather than before his own office door). It being understood that “Joe” was to act as coachman in passing out of Washington, at this moment he was called for, and in the most polite and natural manner, with the fleetness of a young deer, he jumped into the carriage, took the reins and whip, whilst the doctor and William Penn were cordially shaking hands and bidding adieu. This done, the order was given to Joe, “drive on.” Joe bravely obeyed. The faithful horse trotted off willingly, and the doctor sat in his carriage as composed as though he had succeeded in procuring an honorable and lucrative office from the White House, and was returning home to tell his wife the good news. The doctor had some knowledge of the roads, also some acquaintances in Maryland, through which State he had to travel; therefore, after leaving the suburbs of Washington, the doctor took the reins in his own hands, as he felt that he was more experienced as a driver than his young coachman. He was also mindful of the fact, that, before reaching Pennsylvania, his faithful beast would need feeding several times, and that they consequently would be obliged to pass one or two nights at least in Maryland, either at a tavern or farm-house.

In reflecting upon the matter, it occurred to the doctor, that in earlier days, he had been quite intimately acquainted with a farmer and his family (who were slave-holders), in Maryland, and that he would about reach their house at the end of the first day’s journey. He concluded that he could do no better than to renew his acquaintance with his old friends on this occasion. After a very successful day’s travel, night came on, and the doctor was safely at the farmer’s door with his carriage and waiter boy; the doctor was readily recognized by the farmer and his family, who seemed glad to see him; indeed, they made quite a “fuss” over him. As a matter of strategy, the doctor made quite a “fuss” over them in return; nevertheless, he did not fail to assume airs of importance, which were calculated to lead them to think that he had grown older and wiser than when they knew him in his younger days. In casually referring to the manner of his traveling, he alluded to the fact, that he was not very well, and as it had been a considerable length of time since he had been through that part of the country, he thought that the drive would do him good, and especially the sight of old familiar places and people. The farmer and his family felt themselves exceedingly honored by the visit from the distinguished doctor, and manifested a marked willingness to spare no pains to render his night’s lodging in every way comfortable.

The Dr. being an educated and intelligent gentleman, well posted on other questions besides medicine, could freely talk about farming in all its branches, and “niggers” too, in an emergency, so the evening passed off pleasantly with the Dr. in the parlor, and “Joe” in the kitchen. The Dr., however, had given “Joe” precept upon precept, “here a little, and there a little,” as to how he should act in the presence of master white people, or slave colored people, and thus he was prepared to act his part with due exactness. Before the evening grew late, the Dr., fearing some accident, intimated, that he was feeling a “little languid,” and therefore thought that he had better “retire.” Furthermore he added, that he was “liable to vertigo,” when not quite well, and for this reason he must have his boy “Joe” sleep in the room with him. “Simply give him a bed quilt and he will fare well enough in one corner of the room,” said the Dr. The proposal was readily acceded to, and carried into effect by the accommodating host. The Dr. was soon in bed, sleeping soundly, and “Joe,” in his new coat and pants, wrapped up in the bed quilt, in a corner of the room quite comfortably.

The next morning the Dr. arose at as early an hour as was prudent for a gentleman of his position, and feeling refreshed, partook of a good breakfast, and was ready, with his boy, “Joe,” to prosecute their journey. Face, eyes, hope, and steps, were set as flint, Pennsylvania-ward. What time the following day or night they crossed Mason and Dixon’s line is not recorded on the Underground Rail Road books, but at four o’clock on Thanksgiving Day, the Dr. safely landed the “fleeing girl of fifteen” at the residence of the writer in Philadelphia. On delivering up his charge, the Dr. simply remarked to the writer’s wife, “I wish to leave this young lad with you a short while, and I will call and see further about him.” Without further explanation, he stepped into his carriage and hurried away, evidently anxious to report himself to his wife, in order to relieve her mind of a great weight of anxiety on his account. The writer, who happened to be absent from home when the Dr. called, returned soon afterwards. “The Dr. has been here” (he was the family physician), “and left this ‘young lad,’ and said, that he would call again and see about him,” said Mrs. S. The “young lad” was sitting quite composedly in the dining-room, with his cap on. The writer turned to him and inquired, “I suppose you are the person that the Dr. went to Washington after, are you not?” “No,” said “Joe.” “Where are you from then?” was the next question. “From York, sir.” “From York? Why then did the Dr. bring you here?” was the next query, “the Dr. went expressly to Washington after a young girl, who was to be brought away dressed up as a boy, and I took you to be the person.” Without replying “the lad” arose and walked out of the house. The querist, somewhat mystified, followed him, and then when the two were alone, “the lad” said, “I am the one the Dr. went after.” After congratulating her, the writer asked why she had said, that she was not from Washington, but from York. She explained, that the Dr. had strictly charged her not to own to any person, except the writer, that she was from Washington, but from York. As there were persons present (wife, hired girl, and a fugitive woman), when the questions were put to her, she felt that it would be a violation of her pledge to answer in the affirmative. Before this examination, neither of the individuals present for a moment entertained the slightest doubt but that she was a “lad,” so well had she acted her part in every particular. She was dressed in a new suit, which fitted her quite nicely, and with her unusual amount of common sense, she appeared to be in no respect lacking. To send off a prize so rare and remarkable, as she was, without affording some of the stockholders and managers of the Road the pleasure of seeing her, was not to be thought of. In addition to the Vigilance Committee, quite a number of persons were invited to see her, and were greatly astonished. Indeed it was difficult to realize, that she was not a boy, even after becoming acquainted with the facts in the case.

The following is an exact account of this case, as taken from the Underground Rail Road records:

“THANKSGIVING DAY, Nov., 1855.

Arrived, Ann Maria Weems, alias ‘Joe Wright,’ alias ‘Ellen Capron,’ from Washington, through the aid of Dr. H. She is about fifteen years of age, bright mulatto, well grown, smart and good-looking. For the last three years, or about that length of time, she has been owned by Charles M. Price, a negro trader, of Rockville, Maryland. Mr. P. was given to ‘intemperance,’ to a very great extent, and gross ‘profanity.’ He buys and sells many slaves in the course of the year. ‘His wife is cross and peevish.’ She used to take great pleasure in ‘torturing’ one ‘little slave boy.’ He was the son of his master (and was owned by him); this was the chief cause of the mistress’ spite.”

Ann Maria had always desired her freedom from childhood, and although not thirteen, when first advised to escape, she received the suggestion without hesitation, and ever after that time waited almost daily, for more than two years, the chance to flee. Her friends were, of course, to aid her, and make arrangements for her escape. Her owner, fearing that she might escape, for a long time compelled her to sleep in the chamber with “her master and mistress;” indeed she was so kept until about three weeks before she fled. She left her parents living in Washington. Three of her brothers had been sold South from their parents. Her mother had been purchased for $1,000, and one of her sisters for $1,600 for freedom. Before Ann Maria was thirteen years of age $700 was offered for her by a friend, who desired to procure her freedom, but the offer was promptly refused, as were succeeding ones repeatedly made. The only chance of procuring her freedom, depended upon getting her away on the Underground Rail Road. She was neatly attired in male habiliments, and in that manner came all the way from Washington. After passing two or three days with her new friends in Philadelphia, she was sent on (in male attire) to Lewis Tappan, of New York, who had likewise been deeply interested in her case from the beginning, and who held himself ready, as was understood, to cash a draft for three hundred dollars to compensate the man who might risk his own liberty in bringing her on from Washington. After having arrived safely in New York, she found a home and kind friends in the family of the Rev. A.N. Freeman, and received quite an ovation characteristic of an Underground Rail Road.

After having received many tokens of esteem and kindness from the friends of the slave in New York and Brooklyn, she was carefully forwarded on to Canada, to be educated at the “Buxton Settlement.”

An interesting letter, however, from the mother of Ann Maria, conveying the intelligence of her late great struggle and anxiety in laboring to free her last child from Slavery is too important to be omitted, and hence is inserted in connection with this narrative.

LETTER FROM THE MOTHER.

WASHINGTON, D.C., September 19th, 1857.

WM. STILL, ESQ., Philadelphia, Pa. SIR:—I have just sent for my son Augustus, in Alabama. I have sent eleven hundred dollars which pays for his body and some thirty dollars to pay his fare to Washington. I borrowed one hundred and eighty dollars to make out the eleven hundred dollars. I was not very successful in Syracuse. I collected only twelve dollars, and in Rochester only two dollars. I did not know that the season was so unpropitious. The wealthy had all gone to the springs. They must have returned by this time. I hope you will exert yourself and help me get a part of the money I owe, at least. I am obliged to pay it by the 12th of next month. I was unwell when I returned through Philadelphia, or I should have called. I had been from home five weeks.

My son Augustus is the last of the family in Slavery. I feel rejoiced that he is soon to be free and with me, and of course feel the greatest solicitude about raising the one hundred and eighty dollars I have borrowed of a kind friend, or who has borrowed it for me at bank. I hope and pray you will help me as far as possible. Tell Mr. Douglass to remember me, and if he can, to interest his friends for me.

You will recollect that five hundred dollars of our money was taken to buy the sister of Henry H. Garnett’s wife. Had I been able to command this I should not be necessitated to ask the favors and indulgences I do.

I am expecting daily the return of Augustus, and may Heaven grant him a safe deliverance and smile propitiously upon you and all kind friends who have aided in his return to me.

Be pleased to remember me to friends, and accept yourself the blessing and prayers of your dear friend,

EARRO WEEMS.

P.S. Direct your letter to E.L. Stevens, in Duff Green’s Row, Capitol Hill, Washington, D.C.

E.W.

That William Penn who worked so faithfully for two years for the deliverance of Ann Maria may not appear to have been devoting all his time and sympathy towards this single object it seems expedient that two or three additional letters, proposing certain grand Underground Rail Road plans, should have a place here. For this purpose, therefore, the following letters are subjoined.

LETTERS FROM WILLIAM PENN.

WASHINGTON, D.C., Oct. 3, 1854

DEAR SIR:—I address you to-day chiefly at the suggestion of the Lady who will hand you my letter, and who is a resident of your city.

After stating to you, that the case about which I have previously written, remains just as it was when I wrote last—full of difficulty—I thought I would call your attention to another enterprise; it is this: to find a man with a large heart for doing good to the oppressed, who will come to Washington to live, and who will walk out to Penn’a., or a part of the way there, once or twice a week. He will find parties who will pay him for doing so. Parties of say, two, three, five or so, who will pay him at least $5 each, for the privilege of following him, but will never speak to him; but will keep just in sight of him and obey any sign he may give; say, he takes off his hat and scratches his head as a sign for them to go to some barn or wood to rest, &c. No living being shall be found to say he ever spoke to them. A white man would be best, and then even parties led out by him could not, if they would, testify to any understanding or anything else against a white man. I think he might make a good living at it. Can it not be done?

If one or two safe stopping-places could be found on the way—such as a barn or shed, they could walk quite safely all night and then sleep all day—about two, or easily three nights would convey them to a place of safety. The traveler might be a peddler or huckster, with an old horse and cart, and bring us in eggs and butter if he pleases.

Let him once plan out his route, and he might then take ten or a dozen at a time, and they are often able and willing to pay $10 a piece.

I have a hard case now on hand; a brother and sister 23 to 25 years old, whose mother lives in your city. They are cruelly treated; they want to go, they ought to go; but they are utterly destitute. Can nothing be done for such cases? If you can think of anything let me know it. I suppose you know me?

WASHINGTON, D.C., April 3, 1856.

DEAR SIR:—I sent you the recent law of Virginia, under which all vessels are to be searched for fugitives within the waters of that State.

It was long ago suggested by a sagacious friend, that the “powder boy” might find a better port in the Chesapeake bay, or in the Patuxent river to communicate with this vicinity, than by entering the Potomac river, even were there no such law.

Suppose he opens a trade with some place south-west of Annapolis, 25 or 30 miles from here, or less. He might carry wood, oysters, &c., and all his customers from this vicinity might travel in that direction without any of the suspicions that might attend their journeyings towards this city. In this way, doubtless, a good business might be carried on without interruption or competition, and provided the plan was conducted without affecting the inhabitants along that shore, no suspicion would arise as to the manner or magnitude of his business operations. How does this strike you? What does the “powder boy” think of it?

I heretofore intimated a pressing necessity on the part of several females—they are variously situated—two have children, say a couple each; some have none—of the latter, one can raise $50, another, say 30 or 40 dollars—another who was gazetted last August (a copy sent you), can raise, through her friends, 20 or 30 dollars, &c., &c. None of these can walk so far or so fast as scores of men that are constantly leaving. I cannot shake off my anxiety for these poor creatures. Can you think of anything for any of these? Address your other correspondent in answer to this at your leisure.

Yours,

WM. PENN.

P.S.—April 3d. Since writing the above, I have received yours of 31st. I am rejoiced to hear that business is so successful and prosperous—may it continue till the article shall cease to be merchandize.

I spoke in my last letter of the departure of a “few friends.” I have since heard of their good health in Penn’a. Probably you may have seen them.

In reference to the expedition of which you think you can “hold out some little encouragement,” I will barely remark, that I shall be glad, if it is undertaken, to have all the notice of the time and manner that is possible, so as to make ready.

A friend of mine says, anthracite coal will always pay here from Philadelphia, and thinks a small vessel might run often—that she never would be searched in the Potomac, unless she went outside.

You advise caution towards Mr. P. I am precisely of your opinion about him, that he is a “queer stick,” and while I advised him carefully in reference to his own undertakings, I took no counsel of him concerning mine.

Yours,

W.P.

WASHINGTON, D.C., April 23d, 1856.

DEAR SIR:—I have to thank you for your last two encouraging letters of 31st of March and 7th April. I have seen nothing in the papers to interest you, and having bad health and a press of other engagements, I have neglected to write you.

Enclosed is a list of persons referred to in my last letter, all most anxious to travel—all meritorious. In some of these I feel an especial interest for what they have done to help others in distress.

I suggest for yours and the “powder boy’s” consideration the following plan: that he shall take in coal for Washington and come directly here—sell his coal and go to Georgetown for freight, and wait for it. If any fancy articles are sent on board, I understand he has a place to put them in, and if he has I suggest that he lies still, still waiting for freight till the first anxiety is over. Vessels that have just left are the ones that will be inquired after, and perhaps chased. If he lays still a day or two all suspicion will be prevented. If there shall be occasion to refer to any of them hereafter, it may be by their numbers in the list.

The family—5 to 11—will be missed and inquired after soon and urgently; 12 and 13 will also be soon missed, but none of the others.

JOHN HENRY HILL

If all this can be done, some little time or notice must be had to get them all ready. They tell me they can pay the sums marked to their names. The aggregate is small, but as I told you, they are poor. Let me hear from you when convenient.

Truly Yours,

WM. PENN.

1. A woman, may be 40 years old, $40.00 2. A woman, may be 40 years old, with 3 children, say 4, 6, and 8[6] 15.00 3. A sister of the above, younger 10.00 4. A very genteel mulatto girl about 22 25.00 5. A woman, say 45, These are all one 6. A daughter, 18, family, either of 7. A son, 16, them leaving 8. A son, 14, alone, they think, 50.00 9. A daughter, 12, would cause the 10. A son, say 22, balance to be sold. 11. A man, the Uncle, 40, 12. A very genteel mulatto girl, say 23 25.00 13. A very genteel mulatto girl, say 24 25.00

- He had been engaged at different times in carrying powder in his boat from a powder magazine, and from this circumstance, was familiarly called the "Powder Boy." ↵

- Mr. Bigelow's correspondent had been on a visit to the fugitives to Canada. ↵

- Jane Johnson of the Passmore Williamson Slave Case. ↵

- At the time this letter was written, she was then under Mr. B.'s protection in Washington, and had to be so kept for six weeks. His question, therefore, "is she still running with bleeding feet," etc., was simply a precautionary step to blind any who might perchance investigate the matter. ↵

- Dr. T. was one of the professional gentlemen alluded to above, who had expressed a willingness to act as an agent in the matter. ↵

- The children might be left behind" ↵