The Underground Railroad

Wesley Harris Alias Robert Jackson, Craven Matterson and Two Brother

WESLEY HARRIS,[1] ALIAS ROBERT JACKSON, AND THE MATTERSON BROTHERS.

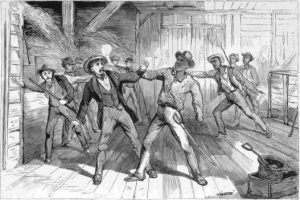

In setting out for freedom, Wesley was the leader of this party. After two nights of fatiguing travel at a distance of about sixty miles from home, the young aspirants for liberty were betrayed, and in an attempt made to capture them a most bloody conflict ensued. Both fugitives and pursuers were the recipients of severe wounds from gun shots, and other weapons used in the contest.

Wesley bravely used his fire arms until almost fatally wounded by one of the pursuers, who with a heavily loaded gun discharged the contents with deadly aim in his left arm, which raked the flesh from the bone for a space of about six inches in length. One of Wesley’s companions also fought heroically and only yielded when badly wounded and quite overpowered. The two younger (brothers of C. Matterson) it seemed made no resistance.

In order to recall the adventures of this struggle, and the success of Wesley Harris, it is only necessary to copy the report as then penned from the lips of this young hero, while on the Underground Rail Road, even then in a very critical state. Most fearful indeed was his condition when he was brought to the Vigilance Committee in this City.

UNDERGROUND RAIL ROAD RECORD.

November 2d, 1853.—Arrived: Robert Jackson (shot man), alias Wesley Harris; age twenty-two years; dark color; medium height, and of slender stature.

Robert was born in Martinsburg, Va., and was owned by Philip Pendleton. From a boy he had always been hired out. At the first of this year he commenced services with Mrs. Carroll, proprietress of the United States Hotel at Harper’s Ferry. Of Mrs. Carroll he speaks in very grateful terms, saying that she was kind to him and all the servants, and promised them their freedom at her death. She excused herself for not giving them their freedom on the ground that her husband died insolvent, leaving her the responsibility of settling his debts.

But while Mrs. Carroll was very kind to her servants, her manager was equally as cruel. About a month before Wesley left, the overseer, for some trifling cause, attempted to flog him, but was resisted, and himself flogged. This resistance of the slave was regarded by the overseer as an unpardonable offence; consequently he communicated the intelligence to his owner, which had the desired effect on his mind as appeared from his answer to the overseer, which was nothing less than instructions that if he should again attempt to correct Wesley and he should repel the wholesome treatment, the overseer was to put him in prison and sell him. Whether he offended again or not, the following Christmas he was to be sold without fail.

Wesley’s mistress was kind enough to apprise him of the intention of his owner and the overseer, and told him that if he could help himself he had better do so. So from that time Wesley began to contemplate how he should escape the doom which had been planned for him.

“A friend,” says he, “by the name of C. Matterson, told me that he was going off. Then I told him of my master’s writing to Mrs. Carroll concerning selling, etc., and that I was going off too. We then concluded to go together. There were two others—brothers of Matterson—who were told of our plan to escape, and readily joined with us in the undertaking. So one Saturday night, at twelve o’clock, we set out for the North. After traveling upwards of two days and over sixty miles, we found ourselves unexpectedly in Terrytown, Md. There we were informed by a friendly colored man of the danger we were in and of the bad character of the place towards colored people, especially those who were escaping to freedom; and he advised us to hide as quickly as we could. We at once went to the woods and hid. Soon after we had secreted ourselves a man came near by and commenced splitting wood, or rails, which alarmed us. We then moved to another hiding-place in a thicket near a farmer’s barn, where we were soon startled again by a dog approaching and barking at us. The attention of the owner of the dog was drawn to his barking and to where we were. The owner of the dog was a farmer. He asked us where we were going. We replied to Gettysburg—to visit some relatives, etc. He told us that we were running off. He then offered friendly advice, talked like a Quaker, and urged us to go with him to his barn for protection. After much persuasion, we consented to go with him.

“Soon after putting us in his barn, himself and daughter prepared us a nice breakfast, which cheered our spirits, as we were hungry. For this kindness we paid him one dollar. He next told us to hide on the mow till eve, when he would safely direct us on our road to Gettysburg. All, very much fatigued from traveling, fell asleep, excepting myself; I could not sleep; I felt as if all was not right.

“About noon men were heard talking around the barn. I woke my companions up and told them that that man had betrayed us. At first they did not believe me. In a moment afterwards the barn door was opened, and in came the men, eight in number. One of the men asked the owner of the barn if he had any long straw. ‘Yes,’ was the answer. So up on the mow came three of the men, when, to their great surprise, as they pretended, we were discovered. The question was then asked the owner of the barn by one of the men, if he harbored runaway negroes in his barn? He answered, ‘No,’ and pretended to be entirely ignorant of their being in his barn. One of the men replied that four negroes were on the mow, and he knew of it. The men then asked us where we were, going. We told them to Gettysburg, that we had aunts and a mother there. Also we spoke of a Mr. Houghman, a gentleman we happened to have some knowledge of, having seen him in Virginia. We were next asked for our passes. We told them that we hadn’t any, that we had not been required to carry them where we came from. They then said that we would have to go before a magistrate, and if he allowed us to go on, well and good. The men all being armed and furnished with ropes, we were ordered to be tied. I told them if they took me they would have to take me dead or crippled. At that instant one of my friends cried out—’Where is the man that betrayed us?’ Spying him at the same moment, he shot him (badly wounding him). Then the conflict fairly began. The constable seized me by the collar, or rather behind my shoulder. I at once shot him with my pistol, but in consequence of his throwing up his arm, which hit mine as I fired, the effect of the load of my pistol was much turned aside; his face, however, was badly burned, besides his shoulder being wounded. I again fired on the pursuers, but do not know whether I hit anybody or not. I then drew a sword, I had brought with me, and was about cutting my way to the door, when I was shot by one of the men, receiving the entire contents of one load of a double barreled gun in my left arm, that being the arm with which I was defending myself. The load brought me to the ground, and I was unable to make further struggle for myself. I was then badly beaten with guns, &c. In the meantime, my friend Craven, who was defending himself, was shot badly in the face, and most violently beaten until he was conquered and tied. The two young brothers of Craven stood still, without making the least resistance. After we were fairly captured, we were taken to Terrytown, which was in sight of where we were betrayed. By this time I had lost so much blood from my wounds, that they concluded my situation was too dangerous to admit of being taken further; so I was made a prisoner at a tavern, kept by a man named Fisher. There my wounds were dressed, and thirty-two shot were taken from my arm. For three days I was crazy, and they thought I would die. During the first two weeks, while I was a prisoner at the tavern, I raised a great deal of blood, and was considered in a very dangerous condition—so much so that persons desiring to see me were not permitted. Afterwards I began to get better, and was then kept privately—was strictly watched day and night. Occasionally, however, the cook, a colored woman (Mrs. Smith), would manage to get to see me. Also James Matthews succeeded in getting to see me; consequently, as my wounds healed, and my senses came to me, I began to plan how to make another effort to escape. I asked one of the friends, alluded to above, to get me a rope. He got it. I kept it about me four days in my pocket; in the meantime I procured three nails. On Friday night, October 14th, I fastened my nails in under the window sill; tied my rope to the nails, threw my shoes out of the window, put the rope in my mouth, then took hold of it with my well hand, clambered into the window, very weak, but I managed to let myself down to the ground. I was so weak, that I could scarcely walk, but I managed to hobble off to a place three quarters of a mile from the tavern, where a friend had fixed upon for me to go, if I succeeded in making my escape. There I was found by my friend, who kept me secure till Saturday eve, when a swift horse was furnished by James Rogers, and a colored man found to conduct me to Gettysburg. Instead of going direct to Gettysburg, we took a different road, in order to shun our pursuers, as the news of my escape had created general excitement. My three other companions, who were captured, were sent to Westminster jail, where they were kept three weeks, and afterwards sent to Baltimore and sold for twelve hundred dollars a piece, as I was informed while at the tavern in Terrytown.”

DESPERATE CONFLICT IN A BARN.

The Vigilance Committee procured good medical attention and afforded the fugitive time for recuperation, furnished him with clothing and a free ticket, and sent him on his way greatly improved in health, and strong in the faith that, “He who would be free, himself must strike the blow.” His safe arrival in Canada, with his thanks, were duly announced. And some time after becoming naturalized, in one of his letters, he wrote that he was a brakesman on the Great Western R.R., (in Canada—promoted from the U.G.R.R.,) the result of being under the protection of the British Lion.

DEATH OF ROMULUS HALL—NEW NAME GEORGE WEEMS.

In March, 1857, Abram Harris fled from John Henry Suthern, who lived near Benedict, Charles county, Md., where he was engaged in the farming business, and was the owner of about seventy head of slaves. He kept an overseer, and usually had flogging administered daily, on males and females, old and young. Abram becoming very sick of this treatment, resolved, about the first of March, to seek out the Underground Rail Road. But for his strong attachment to his wife (who was owned by Samuel Adams, but was “pretty well treated”), he never would have consented to suffer as he did.

Here no hope of comfort for the future seemed to remain. So Abram consulted with a fellow-servant, by the name of Romulus Hall, alias George Weems, and being very warm friends, concluded to start together. Both had wives to “tear themselves from,” and each was equally ignorant of the distance they had to travel, and the dangers and sufferings to be endured. But they “trusted in God” and kept the North Star in view. For nine days and nights, without a guide, they traveled at a very exhausting rate, especially as they had to go fasting for three days, and to endure very cold weather. Abram’s companion, being about fifty years of age, felt obliged to succumb, both from hunger and cold, and had to be left on the way. Abram was a man of medium size, tall, dark chestnut color, and could read and write a little and was quite intelligent; “was a member of the Mount Zion Church,” and occasionally officiated as an “exhorter,” and really appeared to be a man of genuine faith in the Almighty, and equally as much in freedom.

In substance, Abram gave the following information concerning his knowledge of affairs on the farm under his master—

“Master and mistress very frequently visited the Protestant Church, but were not members. Mistress was very bad. About three weeks before I left, the overseer, in a violent fit of bad temper, shot and badly wounded a young slave man by the name of Henry Waters, but no sooner than he got well enough he escaped, and had not been heard of up to the time Abram left. About three years before this happened, an overseer of my master was found shot dead on the road. At once some of the slaves were suspected, and were all taken to the Court House, at Serentown, St. Mary’s county; but all came off clear. After this occurrence a new overseer, by the name of John Decket, was employed. Although his predecessor had been dead three years, Decket, nevertheless, concluded that it was not ‘too late’ to flog the secret out of some of the slaves. Accordingly, he selected a young slave man for his victim, and flogged him so cruelly that he could scarcely walk or stand, and to keep from being actually killed, the boy told an untruth, and confessed that he and his Uncle Henry killed Webster, the overseer; whereupon the poor fellow was sent to jail to be tried for his life.”

But Abram did not wait to hear the verdict. He reached the Committee safely in this city, in advance of his companion, and was furnished with a free ticket and other needed assistance, and was sent on his way rejoicing. After reaching his destination, he wrote back to know how his friend and companion (George) was getting along; but in less than three weeks after he had passed, the following brief story reveals the sad fate of poor Romulus Hall, who had journeyed with him till exhausted from hunger and badly frost-bitten.

A few days after his younger companion had passed on North, Romulus was brought by a pitying stranger to the Vigilance Committee, in a most shocking condition. The frost had made sad havoc with his feet and legs, so much so that all sense of feeling had departed therefrom.

DEATH OF ROMULUS HALL.

How he ever reached this city is a marvel. On his arrival medical attention and other necessary comforts were provided by the Committee, who hoped with himself, that he would be restored with the loss of his toes alone. For one week he seemed to be improving; at the expiration of this time, however, his symptoms changed, indicating not only the end of slavery, but also the end of all his earthly troubles.

Lockjaw and mortification set in in the most malignant form, and for nearly thirty-six hours the unfortunate victim suffered in extreme agony, though not a murmur escaped him for having brought upon himself in seeking his liberty this painful infliction and death. It was wonderful to see how resignedly he endured his fate.

Being anxious to get his testimony relative to his escape, etc., the Chairman of the Committee took his pencil and expressed to him his wishes in the matter. Amongst other questions, he was asked: “Do you regret having attempted to escape from slavery?” After a severe spasm he said, as his friend was about to turn to leave the room, hopeless of being gratified in his purpose: “Don’t go; I have not answered your question. I am glad I escaped from slavery!” He then gave his name, and tried to tell the name of his master, but was so weak he could not be understood.

At his bedside, day and night, Slavery looked more heinous than it had ever done before. Only think how this poor man, in an enlightened Christian land, for the bare hope of freedom, in a strange land amongst strangers, was obliged not only to bear the sacrifice of his wife and kindred, but also of his own life.

Nothing ever appeared more sad than seeing him in a dying posture, and instead of reaching his much coveted destination in Canada, going to that “bourne whence no traveler returns.” Of course it was expedient, even after his death, that only a few friends should follow him to his grave. Nevertheless, he was decently buried in the beautiful Lebanon Cemetery.

In his purse was found one single five cent piece, his whole pecuniary dependence.

This was the first instance of death on the Underground Rail Road in this region.

The Committee were indebted to the medical services of the well-known friends of the fugitive, Drs. J.L. Griscom and H.T. Childs, whose faithful services were freely given; and likewise to Mrs. H.S. Duterte and Mrs. Williams, who generously performed the offices of charity and friendship at his burial.

From his companion, who passed on Canada-ward without delay, we received a letter, from which, as an item of interest, we make the following extract:

“I am enjoying good health, and hope when this reaches you, you may be enjoying the same blessing. Give my love to Mr. ——, and family, and tell them I am in a land of liberty! I am a man among men!” (The above was addressed to the deceased.)

The subjoined letter, from Rev. L.D. Mansfield, expressed on behalf of Romulus’ companion, his sad feelings on hearing of his friend’s death. And here it may not be inappropriate to add, that clearly enough is it to be seen, that Rev. Mansfield was one of the rare order of ministers, who believed it right “to do unto others as one would be done by” in practice, not in theory merely, and who felt that they could no more be excused for “falling down,” in obedience to the Fugitive Slave Law under President Fillmore, than could Daniel for worshiping the “golden image” under Nebuchadnezzar.

AUBURN, NEW YORK, MAY 4TH, 1857.

DEAR BR. STILL:—Henry Lemmon wishes me to write to you in reply to your kind letter, conveying the intelligence of the death of your fugitive guest, Geo. Weems. He was deeply affected at the intelligence, for he was most devotedly attached to him and had been for many years. Mr. Lemmon now expects his sister to come on, and wishes you to aid her in any way in your power—as he knows you will.

He wishes you to send the coat and cap of Weems by his sister when she comes. And when you write out the history of Weems’ escape, and it is published, that you would send him a copy of the papers. He has not been very successful in getting work yet.

Mr. and Mrs. Harris left for Canada last week. The friends made them a purse of $15 or $20, and we hope they will do well.

Mr. Lemmon sends his respects to you and Mrs. Still. Give my kind regards to her and accept also yourself,

Yours very truly,

L.D. MANSFIELD.

* * * * *

JAMES MERCER, WM. H. GILLIAM, AND JOHN CLAYTON.

STOWED AWAY IN A HOT BERTH.

This arrival came by Steamer. But they neither came in State-room nor as Cabin, Steerage, or Deck passengers.

A certain space, not far from the boiler, where the heat and coal dust were almost intolerable,—the colored steward on the boat in answer to an appeal from these unhappy bondmen, could point to no other place for concealment but this. Nor was he at all certain that they could endure the intense heat of that place. It admitted of no other posture than lying flat down, wholly shut out from the light, and nearly in the same predicament in regard to the air. Here, however, was a chance of throwing off the yoke, even if it cost them their lives. They considered and resolved to try it at all hazards.

Henry Box Brown’s sufferings were nothing, compared to what these men submitted to during the entire journey.

They reached the house of one of the Committee about three o’clock, A.M.

All the way from the wharf the cold rain poured down in torrents and they got completely drenched, but their hearts were swelling with joy and gladness unutterable. From the thick coating of coal dust, and the effect of the rain added thereto, all traces of natural appearance were entirely obliterated, and they looked frightful in the extreme. But they had placed their lives in mortal peril for freedom.

Every step of their critical journey was reviewed and commented on, with matchless natural eloquence,—how, when almost on the eve of suffocating in their warm berths, in order to catch a breath of air, they were compelled to crawl, one at a time, to a small aperture; but scarcely would one poor fellow pass three minutes being thus refreshed, ere the others would insist that he should “go back to his hole.” Air was precious, but for the time being they valued their liberty at still greater price.

After they had talked to their hearts’ content, and after they had been thoroughly cleansed and changed in apparel, their physical appearance could be easily discerned, which made it less a wonder whence such outbursts of eloquence had emanated. They bore every mark of determined manhood.

The date of this arrival was February 26, 1854, and the following description was then recorded—

Arrived, by Steamer Pennsylvania, James Mercer, William H. Gilliam and John Clayton, from Richmond.

James was owned by the widow, Mrs. T.E. White. He is thirty-two years of age, of dark complexion, well made, good-looking, reads and writes, is very fluent in speech, and remarkably intelligent. From a boy, he had been hired out. The last place he had the honor to fill before escaping, was with Messrs. Williams and Brother, wholesale commission merchants. For his services in this store the widow had been drawing one hundred and twenty-five dollars per annum, clear of all expenses.

He did not complain of bad treatment from his mistress, indeed, he spoke rather favorably of her. But he could not close his eyes to the fact, that at one time Mrs. White had been in possession of thirty head of slaves, although at the time he was counting the cost of escaping, two only remained—himself and William, (save a little boy) and on himself a mortgage for seven hundred and fifty dollars was then resting. He could, therefore, with his remarkably quick intellect, calculate about how long it would be before he reached the auction block.

He had a wife but no child. She was owned by Mr. Henry W. Quarles. So out of that Sodom he felt he would have to escape, even at the cost of leaving his wife behind. Of course he felt hopeful that the way would open by which she could escape at a future time, and so it did, as will appear by and by. His aged mother he had to leave also.

Wm. Henry Gilliam likewise belonged to the Widow White, and he had been hired to Messrs. White and Brother to drive their bread wagon. William was a baker by trade. For his services his mistress had received one hundred and thirty-five dollars per year. He thought his mistress quite as good, if not a little better than most slave-holders. But he had never felt persuaded to believe that she was good enough for him to remain a slave for her support.

Indeed, he had made several unsuccessful attempts before this time to escape from slavery and its horrors. He was fully posted from A to Z, but in his own person he had been smart enough to escape most of the more brutal outrages. He knew how to read and write, and in readiness of speech and general natural ability was far above the average of slaves.

He was twenty-five years of age, well made, of light complexion, and might be put down as a valuable piece of property.

This loss fell with crushing weight upon the kind-hearted mistress, as will be seen in a letter subjoined which she wrote to the unfaithful William, some time after he had fled.

LETTER FROM MRS. L.E. WHITE.

RICHMOND, 16th, 1854.

DEAR HENRY:—Your mother and myself received your letter; she is much distressed at your conduct; she is remaining just as you left her, she says, and she will never be reconciled to your conduct.

I think Henry, you have acted most dishonorably; had you have made a confidant of me I would have been better off; and you as you are. I am badly situated, living with Mrs. Palmer, and having to put up with everything—your mother is also dissatisfied—I am miserably poor, do not get a cent of your hire or James’, besides losing you both, but if you canreconcileso do. By renting a cheap house, I might have lived, now it seems starvation is before me. Martha and the Doctor are living in Portsmouth, it is not in her power to do much for me. I know you will repent it. I heard six weeks before you went, that you were trying to persuade him off—but we all liked you, and I was unwilling to believe it—however, I leave it in God’s hands He will know what to do. Your mother says that I must tell you servant Jones isdeadand oldMrs. Galt. Kit is well, but we are very uneasy, losing your andJames’ hire, I fear poor little fellow, that he will be obliged to go, as I am compelled to live, and it will be your fault. I am quite unwell, but of course, you don’t care.

Yours,

L.E. WHITE.

If you choose to come back you could. I would do a very good part by you, Toler and Cooke has none.

This touching epistle was given by the disobedient William to a member of the Vigilant Committee, when on a visit to Canada, in 1855, and it was thought to be of too much value to be lost. It was put away with other valuable U.G.R.R. documents for future reference. Touching the “rascality” of William and James and the unfortunate predicament in which it placed the kind-hearted widow, Mrs. Louisa White, the following editorial clipped from the wide-awake Richmond Despatch, was also highly appreciated, and preserved as conclusive testimony to the successful working of the U.G.R.R. in the Old Dominion. It reads thus—

“RASCALITY SOMEWHERE.—We called attention yesterday to the advertisement of two negroes belonging to Mrs. Louisa White, by Toler & Cook, and in the call we expressed the opinion that they were still lurking about the city, preparatory to going off. Mr. Toler, we find, is of a different opinion. He believes that they have already cleared themselves—have escaped to a Free State, and we think it extremely probable that he is in the right. They were both of them uncommonly intelligent negroes. One of them, the one hired to Mr. White, was a tip-top baker. He had been all about the country, and had been in the habit of supplying the U.S. Pennsylvania with bread; Mr. W. having the contract. In his visits for this purpose, of course, he formed acquaintances with all sorts of sea-faring characters; and there is every reason to believe that he has been assisted to get off in that way, along with the other boy, hired to the Messrs. Williams. That the two acted in concert, can admit of no doubt. The question is now to find out how they got off. They must undoubtedly have had white men in the secret. Have we then a nest of Abolition scoundrels among us? There ought to be a law to put a police officer on board every vessel as soon as she lands at the wharf. There is one, we believe for inspecting vessels before they leave. If there is not there ought to be one.

“These negroes belong to a widow lady and constitute all the property she has on earth. They have both been raised with the greatest indulgence. Had it been otherwise, they would never have had an opportunity to escape, as they have done. Their flight has left her penniless. Either of them would readily have sold for $1200; and Mr. Toler advised their owner to sell them at the commencement of the year, probably anticipating the very thing that has happened. She refused to do so, because she felt too much attachment to them. They have made a fine return, truly.”

No comment is necessary on the above editorial except simply to express the hope that the editor and his friends who seemed to be utterly befogged as to how these “uncommonly intelligent negroes” made their escape, will find the problem satisfactorily solved in this book.

However, in order to do even-handed justice to all concerned, it seems but proper that William and James should be heard from, and hence a letter from each is here appended for what they are worth. True they were intended only for private use, but since the “True light” (Freedom) has come, all things may be made manifest.

LETTER FROM WILLIAM HENRY GILLIAM.

ST. CATHARINES, C.W., MAY 15th, 1854.

My Dear Friend:—I receaved yours, Dated the 10th and the papers on the 13th, I also saw the pice that was in Miss Shadd’s paper About me. I think Tolar is right About my being in A free State, I am and think A great del of it. Also I have no compassion on the penniless widow lady, I have Served her 25 yers 2 months, I think that is long Enough for me to live A Slave. Dear Sir, I am very sorry to hear of the Accadent that happened to our Friend Mr. Meakins, I have read the letter to all that lives in St. Catharines, that came from old Virginia, and then I Sented to Toronto to Mercer & Clayton to see, and to Farman to read fur themselves. Sir, you must write to me soon and let me know how Meakins gets on with his tryal, and you must pray for him, I have told all here to do the same for him. May God bless and protect him from prison, I have heard A great del of old Richmond and Norfolk. Dear Sir, if you see Mr. or Mrs. Gilbert Give my love to them and tell them to write to me, also give my respect to your Family and A part for yourself, love from the friends to you Soloman Brown, H. Atkins, Was. Johnson, Mrs. Brooks, Mr. Dykes. Mr. Smith is better at presant. And do not forget to write the News of Meakin’s tryal. I cannot say any more at this time; but remain yours and A true Friend ontell Death.

W.H. GILLIAM, the widow’s Mite.

“Our friend Minkins,” in whose behalf William asks the united prayers of his friends, was one of the “scoundrels” who assisted him and his two companions to escape on the steamer. Being suspected of “rascality” in this direction, he was arrested and put in jail, but as no evidence could be found against him he was soon released.

JAMES MERCER’S LETTER.

TORONTO, MARCH 17th, 1854.

My dear friend Still:—I take this method of informing you that I am well, and when this comes to hand it may find you and your family enjoying good health. Sir, my particular for writing is that I wish to hear from you, and to hear all the news from down South. I wish to know if all things are working Right for the Rest of my Brotheran whom in bondage. I will also Say that I am very much please with Toronto, So also the friends that came over with. It is true that we have not been Employed as yet; but we are in hopes of be’en so in a few days. We happen here in good time jest about time the people in this country are going work. I am in good health and good Spirits, and feeles Rejoiced in the Lord for my liberty. I Received cople of paper from you to-day. I wish you see James Morris whom or Abram George the first and second on the Ship Penn., give my respects to them, and ask James if he will call at Henry W. Quarles on May street oppisit the Jews synagogue and call for Marena Mercer, give my love to her ask her of all the times about Richmond, tell her to Send me all the news. Tell Mr. Morris that there will be no danger in going to that place. You will also tell M. to make himself known to her as she may know who sent him. And I wish to get a letter from you.

JAMES M. MERCER.

JOHN H. HILL’S LETTER.

My friend, I would like to hear from you, I have been looking for a letter from you for Several days as the last was very interesting to me, please to write Right away.

Yours most Respectfully,

JOHN H. HILL.

Instead of weeping over the sad situation of his “penniless” mistress and showing any signs of contrition for having wronged the man who held the mortgage of seven hundred and fifty dollars on him, James actually “feels rejoiced in the Lord for his liberty,” and is “very much pleased with Toronto;” but is not satisfied yet, he is even concocting a plan by which his wife might be run off from Richmond, which would be the cause of her owner (Henry W. Quarles, Esq.) losing at least one thousand dollars,

ST. CATHARINE, CANADA, JUNE 8th, 1854.

MR. STILL, DEAR FRIEND:—I received a letter from the poor old widow, Mrs. L.E. White, and she says I may come back if I choose and she will do a good part by me. Yes, yes I am choosing the western side of the South for my home. She is smart, but cannot bung my eye, so she shall have to die in the poor house at last, so she says, and Mercer and myself will be the cause of it. That is all right. I am getting even with her now for I was in the poor house for twenty-five years and have just got out. And she said she knew I was coming away six weeks before I started, so you may know my chance was slim. But Mr. John Wright said I came off like a gentleman and he did not blame me for coming for I was a great boy. Yes I here him enough he is all gas. I am in Canada, and they cannot help themselves.

About that subject I will not say anything more. You must write to me as soon as you can and let me here the news and how the Family is and yourself. Let me know how the times is with the U.G.R.R. Co. Is it doing good business? Mr. Dykes sends his respects to you. Give mine to your family.

Your true friend,

W.H. GILLIAM.

John Clayton, the companion in tribulation of William and James, must not be lost sight of any longer. He was owned by the Widow Clayton, and was white enough to have been nearly related to her, being a mulatto. He was about thirty-five years of age, a man of fine appearance, and quite intelligent. Several years previous he had made an attempt to escape, but failed. Prior to escaping in this instance, he had been laboring in a tobacco factory at $150 a year. It is needless to say that he did not approve of the “peculiar institution.” He left a wife and one child behind to mourn after him. Of his views of Canada and Freedom, the following frank and sensible letter, penned shortly after his arrival, speaks for itself—

TORONTO, March 6th, 1854.

DEAR MR. STILL:—I take this method of informing you that I am well both in health and mind. You may rest assured that I fells myself a free man and do not fell as I did when I was in Virginia thanks be to God I have no master into Canada but I am my own man. I arrived safe into Canada on friday last. I must request of you to write a few lines to my wife and jest state to her that her friend arrived safe into this glorious land of liberty and I am well and she will make very short her time in Virginia. tell her that I likes here very well and hopes to like it better when I gets to work I don’t meane for you to write the same words that are written above but I wish you give her a clear understanding where I am and Shall Remain here untel She comes or I hears from her.

Nothing more at present but remain yours most respectfully,

JOHN CLAYTON.

You will please to direct the to Petersburg Luenena Johns or Clayton John is best.

- Shot by slave-hunters. ↵