The Underground Railroad

The Arrivals of a Single Month

SIXTY PASSENGERS CAME IN ONE MONTH—TWENTY-EIGHT IN ONE ARRIVAL—GREAT PANIC AND INDIGNATION MEETING—INTERESTING CORRESPONDENCE FROM MASTERS AND FUGITIVES.

The great number of cases to be here noticed forbids more than a brief reference to each passenger. As they arrived in parties, their narratives will be given in due order as found on the book of records:

William Griffen, Henry Moor, James Camper, Noah Ennells and Levin Parker. This party came from Cambridge, Md.

William is thirty-four years of age, of medium size and substantial appearance. He fled from James Waters, Esq., a lawyer, living in Cambridge. He was “wealthy, close, and stingy,” and owned nine head of slaves and a farm, on which William served. He was used very hard, which was the cause of his escape, though the idea that he was entitled to his freedom had been entertained for the previous twelve years. On preparing to take the Underground, he armed himself with a big butcher-knife, and resolved, if attacked, to make his enemies stand back. His master was a member of the Methodist Church.

Henry is tall, copper-colored, and about thirty years of age. He complained not so much of bad usage as of the utter distaste he had to working all the time for the “white people for nothing.” He was also decidedly of the opinion that every man should have his liberty. Four years ago his wife was “sold away to Georgia” by her young master; since which time not a word had he heard of her. She left three children, and he, in escaping, also had to leave them in the same hands that sold their mother. He was owned by Levin Dale, a farmer near Cambridge. Henry was armed with a six-barreled revolver, a large knife, and a determined mind.

James is twenty-four years of age, quite black, small size, keen look, and full of hope for the “best part of Canada.” He fled from Henry Hooper, “a dashing young man and a member of the Episcopal Church.” Left because he “did not enjoy privileges” as he wished to do. He was armed with two pistols and a dirk to defend himself.

Noah is only nineteen, quite dark, well-proportioned, and possessed of a fair average of common sense. He was owned by “Black-head Bill LeCount,” who “followed drinking, chewing tobacco, catching ‘runaways,’ and hanging around the court-house.” However, he owned six head of slaves, and had a “rough wife,” who belonged to the Methodist Church. Left because he “expected every day to be sold”—his master being largely in “debt.” Brought with him a butcher-knife.

Levin is twenty-two, rather short built, medium size and well colored. He fled from Lawrence G. Colson, “a very bad man, fond of drinking, great to fight and swear, and hard to please.” His mistress was “real rough; very bad, worse than he was as ‘fur’ as she could be.” Having been stinted with food and clothing and worked hard, was the apology offered by Levin for running off.

Stebney Swan, John Stinger, Robert Emerson, Anthony Pugh and Isabella ——. This company came from Portsmouth, Va. Stebney is thirty-four years of age, medium size, mulatto, and quite wide awake. He was owned by an oysterman by the name of Jos. Carter, who lived near Portsmouth. Naturally enough his master “drank hard, gambled” extensively, and in every other respect was a very ordinary man. Nevertheless, he “owned twenty-five head,” and had a wife and six children. Stebney testified that he had not been used hard, though he had been on the “auction-block three times.” Left because he was “tired of being a servant.” Armed with a broad-axe and hatchet, he started, joined by the above-named companions, and came in a skiff, by sea. Robert Lee was the brave Captain engaged to pilot this Slavery-sick party from the prison-house of bondage. And although every rod of rowing was attended with inconceivable peril, the desired haven was safely reached, and the overjoyed voyagers conducted to the Vigilance Committee.

John is about forty years of age, and so near white that a microscope would be required to discern his colored origin. His father was white, and his mother nearly so. He also had been owned by the oysterman alluded to above; had been captain of one of his oyster-boats, until recently. And but for his attempt some months back to make his escape, he might have been this day in the care of his kind-hearted master. But, because of this wayward step on the part of John, his master felt called upon to humble him. Accordingly, the captaincy was taken from him, and he was compelled to struggle on in a less honorable position. Occasionally John’s mind would be refreshed by his master relating the hard times in the North, the great starvation among the blacks, etc. He would also tell John how much better off he was as a “slave with a kind master to provide for all his wants,” etc. Notwithstanding all this counsel, John did not rest contented until he was on the Underground Rail Road.

Robert was only nineteen, with an intelligent face and prepossessing manners; reads, writes and ciphers; and is about half Anglo-Saxon. He fled from Wm. H. Wilson, Esq., Cashier of the Virginia Bank. Until within the four years previous to Robert’s escape, the cashier was spoken of as a “very good man;” but in consequence of speculations in a large Hotel in Portsmouth, and the then financial embarrassments, “he had become seriously involved,” and decidedly changed in his manners. Robert noticed this, and concluded he had “better get out of danger as soon as possible.”

Anthony and Isabella were an engaged couple, and desired to cast their lot where husband and wife could not be separated on the auction-block.

The following are of the Cambridge party, above alluded to. All left together, but for prudential reasons separated before reaching Philadelphia. The company that left Cambridge on the 24th of October may be thus recognized: Aaron Cornish and wife, with their six children; Solomon, George Anthony, Joseph, Edward James, Perry Lake, and a nameless babe, all very likely; Kit Anthony and wife Leah, and three children, Adam, Mary, and Murray; Joseph Hill and wife Alice, and their son Henry; also Joseph’s sister. Add to the above, Marshall Button and George Light, both single young men, and we have twenty-eight in one arrival, as hearty-looking, brave and interesting specimens of Slavery as could well be produced from Maryland. Before setting out they counted well the cost. Being aware that fifteen had left their neighborhood only a few days ahead of them, and that every slave-holder and slave-catcher throughout the community, were on the alert, and raging furiously against the inroads of the Underground Rail Road, they provided themselves with the following weapons of defense: three revolvers, three double-barreled pistols, three single-barreled pistols, three sword-canes, four butcher knives, one bowie-knife, and one paw.[1] Thus, fully resolved upon freedom or death, with scarcely provisions enough for a single day, while the rain and storm was piteously descending, fathers and mothers with children in their arms (Aaron Cornish had two)—the entire party started. Of course, their provisions gave out before they were fairly on the way, but not so with the storm. It continued to pour upon them for nearly three days. With nothing to appease the gnawings of hunger but parched corn and a few dry crackers, wet and cold, with several of the children sick, some of their feet bare and worn, and one of the mothers with an infant in her arms, incapable of partaking of the diet,—it is impossible to imagine the ordeal they were passing. It was enough to cause the bravest hearts to falter. But not for a moment did they allow themselves to look back. It was exceedingly agreeable to hear even the little children testify that in the most trying hour on the road, not for a moment did they want to go back. The following advertisement, taken from The Cambridge Democrat of November 4, shows how the Rev. Levi Traverse felt about Aaron—

$300 Reward.—Ran away from the subscriber, from the neighborhood of Town Point, on Saturday night, the 24th inst., my negro man, AARON CORNISH, about 35 years old. He is about five feet ten inches high, black, good-looking, rather pleasant countenance, and carries himself with a confident manner. He went off with his wife, DAFFNEY, a negro woman belonging to Reuben E. Phillips. I will give the above reward if taken out of the county, and $200 if taken in the county; in either case to be lodged in Cambridge Jail.

October 25, 1857.

Levi D. Traverse.

To fully understand the Rev. Mr. Traverse’s authority for taking the liberty he did with Aaron’s good name, it may not be amiss to give briefly a paragraph of private information from Aaron, relative to his master. The Rev. Mr. Traverse belonged to the Methodist Church, and was described by Aaron as a “bad young man; rattle-brained; with the appearance of not having good sense,—not enough to manage the great amount of property (he had been left wealthy) in his possession.” Aaron’s servitude commenced under this spiritual protector in May prior to the escape, immediately after the death of his old master. His deceased master, William D. Traverse, by the way, was the father-in-law, and at the same time own uncle of Aaron’s reverend owner. Though the young master, for marrying his own cousin and uncle’s daughter, had been for years the subject of the old gentleman’s wrath, and was not allowed to come near his house, or to entertain any reasonable hope of getting any of his father-in-law’s estate, nevertheless, scarcely had the old man breathed his last, ere the young preacher seized upon the inheritance, slaves and all; at least he claimed two-thirds, allowing for the widow one-third. Unhesitatingly he had taken possession of all the slaves (some thirty head), and was making them feel his power to the fullest extent. To Aaron this increased oppression was exceedingly crushing, as he had been hoping at the death of his old master to be free. Indeed, it was understood that the old man had his will made, and freedom provided for the slaves. But, strangely enough, at his death no will could be found. Aaron was firmly of the conviction that the Rev. Mr. Traverse knew what became of it. Between the widow and the son-in-law, in consequence of his aggressive steps, existed much hostility, which strongly indicated the approach of a law-suit; therefore, except by escaping, Aaron could not see the faintest hope of freedom. Under his old master, the favor of hiring his time had been granted him. He had also been allowed by his wife’s mistress (Miss Jane Carter, of Baltimore), to have his wife and children home with him—that is, until his children would grow to the age of eight and ten years, then they would be taken away and hired out at twelve or fifteen dollars a year at first. Her oldest boy, sixteen, hired the year he left for forty dollars. They had had ten children; two had died, two they were compelled to leave in chains; the rest they brought away. Not one dollar’s expense had they been to their mistress. The industrious Aaron not only had to pay his own hire, but was obliged to do enough over-work to support his large family.

Though he said he had no special complaint to make against his old master, through whom he, with the rest of the slaves, hoped to obtain freedom, Aaron, nevertheless, spoke of him as a man of violent temper, severe on his slaves, drinking hard, etc., though he was a man of wealth and stood high in the community. One of Aaron’s brothers, and others, had been sold South by him. It was on account of his inveterate hatred of his son-in-law, who, he declared, should never have his property (having no other heir but his niece, except his widow), that the slaves relied on his promise to free them. Thus, in view of the facts referred to, Aaron was led to commit the unpardonable sin of running away with his wife Daffney, who, by the way, looked like a woman fully capable of taking care of herself and children, instead of having them stolen away from her, as though they were pigs.

Joseph Viney and family—Joseph was “held to service or labor,” by Charles Bryant, of Alexandria, Va. Joseph had very nearly finished paying for himself. His wife and children were held by Samuel Pattison, Esq., a member of the Methodist Church, “a great big man,” “with red eyes, bald head, drank pretty freely,” and in the language of Joseph, “wouldn’t bear nothing.” Two of Joseph’s brothers-in-law had been sold by his master. Against Mrs. Pattison his complaint was, that “she was mean, sneaking, and did not want to give half enough to eat.”

For the enlightenment of all Christendom, and coming posterity especially, the following advertisement and letter are recorded, with the hope that they will have an important historical value. The writer was at great pains to obtain these interesting documents, directly after the arrival of the memorable Twenty-Eight; and shortly afterwards furnished to the New York Tribune, in a prudential manner, a brief sketch of these very passengers, including the advertisements, but not the letter. It was safely laid away for history—

$2,000 REWARD.—Ran away from the subscriber on Saturday night, the 24th inst, FOURTEEN HEAD OF NEGROES, viz: Four men, two women, one boy and seven children. KIT is about 35 years of age, five feet six or seven inches high, dark chestnut color, and has a scar on one of his thumbs. JOE is about 30 years old, very black, his teeth are very white, and is about five feet eight inches high. HENRY is about 22 years old, five feet ten inches high, of dark chestnut color and large front teeth. JOE is about 20 years old, about five feet six inches high, heavy built and black. TOM is about 16 years old, about five feet high, light chestnut color. SUSAN is about 35 years old, dark chestnut color, and rather stout built; speaks rather slow, and has with her FOUR CHILDREN, varying from one to seven years of age. LEAH is about 28 years old, about five feet high, dark chestnut color, with THREE CHILDREN, two boys and one girl, from one to eight years old.

I will give $1,000 if taken in the county, $1,500 if taken out of the county and in the State, and $2,000 if taken out of the State; in either case to be lodged in Cambridge (Md.) Jail, so that I can get them again; or I will give a fair proportion of the above reward if any part be secured.

SAMUEL PATTISON,

October 26, 1857.

Near Cambridge, Md.

P.S.—Since writing the above, I have discovered that my negro woman, SARAH JANE, 25 years old, stout built and chestnut color, has also run off.

S.P.

SAMUEL PATTISON’S LETTER.

CAMBRIDGE, Nov. 16th, 1857.

L.W. THOMPSON:—SIR, this morning I received your letter wishing an accurate description of my Negroes which ran away on the 24th of last month and the amt of reward offered &c &c. The description is as follows.Kitis about 35 years old, five feet, six or seven inches high, dark chestnut color and has a scar on one of his thumbs, he has a veryquick step and walks very straight, and can read and write.Joe, is about 30 years old, very black and about five feet eight inches high, has a very pleasing appearance, he has a free wife who left with him she is a light molatoo, she has a child not over one year old.Henryis about 22 years old, five feet, ten inches high, of dark chestnut coller and large front teeth, he stoops a little in his walk and has a downward look.Joeis about 20 years old, about five feet six inches high, heavy built, and has a grum look and voice dull, and black.Tomis about 16 years old about five feet high light chestnut coller, smart active boy, and swagers in his walk. Susan is about 35 years old, dark chesnut coller and stout built, speaks rather slow and has with herfour children, three boysand onegirl—the girl has a thumb or finger on her left hand (part of it) cut off, the children are from 9 months to 8 years old. (the youngest a boy 9 months and the oldest whose name is Lloyd is about 8 years old) The husband of Susan (Joe Viney) started off with her, he is a slave, belonging to a gentleman in Alexandria D.C. he is about 40 years old and dark chesnut coller rather slender built and about five feet seven or eight inches high, he is also the Father of Henry, Joe and Tom. Arewardof $400. will be given for his apprehension.Leahis about 28 years old about five feet high dark chesnut coller, with three children. 2 Boys and 1 girl, they are from one to eight years old, the oldest boy is called Adam, Leah is the wife of Kit, the first named man in the list.Sarah Janeis about 25 years old, stout built and chesnut coller, quick and active in her walk. Making in all 15 head, men, women and children belonging to me, or 16 head including Joe Viney, the husband of my woman Susan.

A Rewardof $2250. will be given for my negroes if taken out of the State of Maryland and lodged in Cambridge or Baltimore Jail, so that I can get them or a fair proportion for any part of them. And including Joe Viney’s reward $2650.00.

At the same time eight other negroes belonging to a neighbor of mine ran off, for which a reward of $1400.00 has been offered for them.

If you should want any information, witnesses to prove or indentify the negroes, write immediately on to me. Or if you should need any information with regard to proving the negroes, before I could reach Philadelphia, you can call on Mr. Burroughs at Martin & Smith’s store, Market Street, No 308. Phila and he can refer you to a gentleman who knows the negroes.

Yours &c SAML. PATTISON.

This letter was in answer to one written in Philadelphia and signed, “L.W. Thompson.” It is not improbable that Mr. Pattison’s loss had produced such a high state of mental excitement that he was hardly in a condition for cool reflection, or he would have weighed the matter a little more carefully before exposing himself to the U.G.R.R. agents. But the letter possesses two commendable features, nevertheless. It was tolerably well written and prompt.

Here is a wonderful exhibition of affection for his contented and happy negroes. Whether Mr. Pattison suspended on suddenly learning that he was minus fifteen head, the writer cannot say. But that there was a great slave hunt in every direction there is no room to doubt. Though much more might be said about the parties concerned, it must suffice to add that they came to the Vigilance Committee in a very sad plight—in tattered garments, hungry, sick, and penniless; but they were kindly clothed, fed, doctored, and sent on their way rejoicing.

Daniel Stanly, Nat Amby, John Scott, Hannah Peters, Henrietta Dobson, Elizabeth Amby, Josiah Stanly, Caroline Stanly, Daniel Stanly, jr., John Stanly and Miller Stanly (arrival from Cambridge.) Daniel is about 35, well-made and wide-awake. Fortunately, in emancipating himself, he also, through great perseverance, secured the freedom of his wife and six children; one child he was compelled to leave behind. Daniel belonged to Robert Calender, a farmer, and, “except when in a passion,” said to be “pretty clever.” However, considering as a father, that it was his “duty to do all he could” for his children, and that all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy, Daniel felt bound to seek refuge in Canada. His wife and children were owned by “Samuel Count, an old, bald-headed, bad man,” who “had of late years been selling and buying slaves as a business,” though he stood high and was a “big bug in Cambridge.” The children were truly likely-looking.

Nat is no ordinary man. Like a certain other Nat known to history, his honest and independent bearing in every respect was that of a natural hero. He was full black, and about six feet high; of powerful physical proportions, and of more than ordinary intellectual capacities. With the strongest desire to make the Port of Canada safely, he had resolved to be “carried back,” if attacked by the slave hunters, “only as a dead man.” He was held to service by John Muir, a wealthy farmer, and the owner of 40 or 50 slaves. “Muir would drink and was generally devilish.” Two of Nat’s sisters and one of his brothers had been “sold away to Georgia by him.” Therefore, admonished by threats and fears of having to pass through the same fiery furnace, Nat was led to consider the U.G.R.R. scheme. It was through the marriage of Nat’s mistress to his present owner that he came into Muir’s hands. “Up to the time of her death,” he had been encouraged to “hope” that he would be “free;” indeed, he was assured by her “dying testimony that the slaves were not to be sold.” But regardless of the promises and will of his departed wife, Muir soon extinguished all hopes of freedom from that quarter. But not believing that God had put one man here to “be the servant of another—to work,” and get none of the benefit of his labor, Nat armed himself with a good pistol and a big knife, and taking his wife with him, bade adieu forever to bondage. Observing that Lizzie (Nat’s wife) looked pretty decided and resolute, a member of the committee remarked, “Would your wife fight for freedom?” “I have heard her say she would wade through blood and tears for her freedom,” said Nat, in the most serious mood.

The following advertisement from The Cambridge Democrat of Nov. 4, speaks for itself—

$300 REWARD.—Ran away from the subscriber, on Saturday night last, 17th inst., my negro woman Lizzie, about 28 years old. She is medium sized, dark complexion, good-looking, with rather a down look. When spoken to, replies quickly. She was well dressed, wearing a red and green blanket shawl, and carried with her a variety of clothing. She ran off in company with her husband, Nat Amby (belonging to John Muir, Esq.), who is about 6 feet in height, with slight impediment in his speech, dark chestnut color, and a large scar on the side of his neck.

I will give the above reward if taken in this County, or one-half of what she sells for if taken out of the County or State. In either ease to be lodged in Cambridge Jail.

Cambridge, Oct. 21, 1857.

ALEXANDER H. BAYLY.

P.S.—For the apprehension of the above-named negro man Nat, and delivery in Cambridge Jail, I will give $500 reward.

JOHN MUIR.

Now since Nat’s master has been introduced in the above order, it seems but appropriate that Nat should be heard too; consequently the following letter is inserted for what it is worth:

Auburn, June 10th, 1858.

Mr. William Still:—Sir, will you be so Kind as to write a letter to affey White in straw berry alley in Baltimore city on the point. Say to her at nat Ambey that I wish to Know from her the Last Letar that Joseph Ambie and Henry Ambie two Brothers and Ann Warfield a couisin of them two boys I state above. I would like to hear from my mother sichy Ambie you will Please write to my mother and tell her that I am well and doing well and state to her that I perform my Relissius dutys and I would like to hear from her and want to know if she is performing her Relissius dutys yet and send me word from all her children I left behind say to affey White that I wish her to write me a Letter in Hast my wife is well and doing well and my nephew is doing well. Please tell affey White when she writes to me to Let me know where Joseph and Henry Ambie is.

Mr. Still Please Look on your Book and you will find my name on your Book. They was eleven of us children and all when we came through and I feal interrested about my Brothers. I have never heard from them since I Left home you will Please Be Kind annough to attend to this Letter. When you send the answer to this Letter you will Please send it to P.R. Freeman Auburn City Cayuga County New York.

Yours Truly

NAT AMBIE.

William is 25, complexion brown, intellect naturally good, with no favorable notions of the peculiar institution. He was armed with a formidable dirk-knife, and declared he would use it if attacked, rather than be dragged back to bondage.

Hannah is a hearty-looking young woman of 23 or 24, with a countenance that indicated that liberty was what she wanted and was contending for, and that she could not willingly submit to the yoke. Though she came with the Cambridge party, she did not come from Cambridge, but from Marshall Hope, Caroline County, where she had been owned by Charles Peters, a man who had distinguished himself by getting “drunk, scratching and fighting, etc.,” not unfrequently in his own family even. She had no parents that she knew of. Left because they used her “so bad, beat and knocked” her about.

“Jack Scott.” Jack is about thirty-six years of age, substantially built, dark color, and of quiet and prepossessing manners. He was owned by David B. Turner, Esq., a dry goods merchant of New York. By birth, Turner was a Virginian, and a regular slave-holder. His slaves were kept hired out by the year. As Jack had had but slight acquaintance with his New York owner, he says but very little about him. He was moved to leave simply because he had got tired of working for the “white people for nothing.” Fled from Richmond, Va. Jack went to Canada direct. The following letter furnishes a clew to his whereabouts, plans, etc.

MONTREAL, September 1st 1859.

DEAR SIR:—It is with extreme pleasure that I set down to inclose you a few lines to let you know that I am well & I hope when these few lines come to hand they may find you & your family in good health and prosperity I left your house Nov. 3d, 1857, for Canada I Received a letter here from James Carter in Peters burg, saying that my wife would leave there about the 28th or the first September and that he would send her on by way of Philadelphia to you to send on to Montreal if she come on you be please to send her on and as there is so many boats coming here all times a day I may not know what time she will. So you be please to give her this direction, she can get a cab and go to the Donegana Hotel and Edmund Turner is there he will take you where I lives and if he is not there cabman take you to Mr Taylors on Durham St. nearly opposite to the Methodist Church. Nothing more at present but Remain your well wisher

JOHN SCOTT.

C. Hitchens.—This individual took his departure from Milford, Del., where he was owned by Wm. Hill, a farmer, who took special delight in having “fighting done on the place.” This passenger was one of our least intelligent travelers. He was about 22.

Major Ross.—Major fled from John Jay, a farmer residing in the neighborhood of Havre de Grace, Md. But for the mean treatment received from Mr. Jay, Major might have been foolish enough to have remained all his days in chains. “It’s an ill wind that blows nobody any good.”

Henry Oberne.—Henry was to be free at 28, but preferred having it at 21, especially as he was not certain that 28 would ever come. He is of chestnut color, well made, &c., and came from Seaford, Md.

Perry Burton.—Perry is about twenty-seven years of age, decidedly colored, medium size, and only of ordinary intellect. He acknowledged John R. Burton, a farmer on Indian River, as his master, and escaped because he wanted “some day for himself.”

Alfred Hubert, Israel Whitney and John Thompson. Alfred is of powerful muscular appearance and naturally of a good intellect. He is full dark chestnut color, and would doubtless fetch a high price. He was owned by Mrs. Matilda Niles, from whom he had hired his time, paying $110 yearly. He had no fault to find with his mistress, except he observed she had a young family growing up, into whose hands he feared he might unluckily fall some day, and saw no way of avoiding it but by flight. Being only twenty-eight, he may yet make his mark.

Israel was owned by Elijah Money. All that he could say in favor of his master was, that he treated him “respectfully,” though he “drank hard.” Israel was about thirty-six, and another excellent specimen of an able-bodied and wide-awake man. He hired his time at the rate of $120 a year, and had to find his wife and child in the bargain. He came from Alexandria, Va.

INTERESTING LETTER FROM ISRAEL.

HAMILTON, Oct. 16, 1858.

WILLIAM STILL—My Dear Friend:—I saw Carter and his friend a few days ago, and they told me, that you was well. On the seventh of October my wife came to Hamilton. Mr. A. Hurberd, who came from Virginia with me, is going to get married the 20th ofNovember, next. I wish you would write to me how many of my friends you have seen since October, 1857. Montgomery Green keeps a barber shop in Cayuga, in the State of New York. I have not heard of Oscar Ball but once since I came here, and then he was well and doing well. George Carroll is in Hamilton. The times are very dull at present, and have been ever since I came here. Please write soon. Nothing more at present, only I still remain in Hamilton, C.W.

ISRAEL WHITNEY.

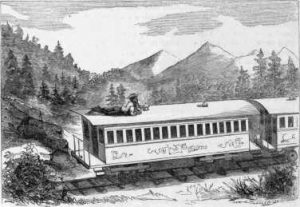

John is nineteen years of age, mulatto, spare made, but not lacking in courage, mother wit or perseverance. He was born in Fauquier county, Va., and, after experiencing Slavery for a number of years there—being sold two or three times to the “highest bidder”—he was finally purchased by a cotton planter named Hezekiah Thompson, residing at Huntsville, Alabama. Immediately after the sale Hezekiah bundled his new “purchase” off to Alabama, where he succeeded in keeping him only about two years, for at the end of that time John determined to strike a blow for liberty. The incentive to this step was the inhuman treatment he was subjected to. Cruel indeed did he find it there. His master was a young man, “fond of drinking and carousing, and always ready for a fight or a knock-down.” A short time before John left his master whipped him so severely with the “bull whip” that he could not use his arm for three or four days. Seeing but one way of escape (and that more perilous than the way William and Ellen Craft, or Henry Box Brown traveled), he resolved to try it. It was to get on the top of the car, instead of inside of it, and thus ride of nights, till nearly daylight, when, at a stopping-place on the road, he would slip off the car, and conceal himself in the woods until under cover of the next night he could manage to get on the top of another car. By this most hazardous mode of travel he reached Virginia.

It may be best not to attempt to describe how he suffered at the hands of his owners in Alabama; or how severely he was pinched with hunger in traveling; or how, when he reached his old neighborhood in Virginia, he could not venture to inquire for his mother, brothers or sisters, to receive from them an affectionate word, an encouraging smile, a crust of bread, or a drink of water.

Success attended his efforts for more than two weeks; but alas, after having got back north of Richmond, on his way home to Alexandria, he was captured and put in prison; his master being informed of the fact, came on and took possession of him again. At first he refused to sell him; said he “had money enough and owned about thirty slaves;” therefore wished to “take him back to make an example of him.” However, through the persuasion of an uncle of his, he consented to sell. Accordingly, John was put on the auction-block and bought for $1,300 by Green McMurray, a regular trader in Richmond. McMurray again offered him for sale, but in consequence of hard times and the high price demanded, John did not go off, at least not in the way the trader desired to dispose of him, but did, nevertheless, succeed in going off on the Underground Rail Road. Thus once more he reached his old home, Alexandria. His mother was in one place, and his six brothers and sisters evidently scattered, where he knew not. Since he was five years of age, not one of them had he seen.

If such sufferings and trials were not entitled to claim for the sufferer the honor of a hero, where in all Christendom could one be found who could prove a better title to that appellation?

It is needless to say that the Committee extended to him brotherly kindness, sympathized with him deeply, and sent him on his way rejoicing.

Of his subsequent career the following extract from a letter written at London shows that he found no rest for the soles of his feet under the Stars and Stripes in New York:

I hope that you will remember John Thompson, who passed through your hands, I think, in October, 1857, at the same time that Mr. Cooper, from Charleston, South Carolina, came on. I was engaged at New York, in the barber business, with a friend, and was doing very well, when I was betrayed and obliged to sail for England very suddenly, my master being in the city to arrest me.

(LONDON, December 21st, 1860.)

JEREMIAH COLBURN.—Jeremiah is a bright mulatto, of prepossessing appearance, reads and writes, and is quite intelligent. He fled from Charleston, where he had been owned by Mrs. E. Williamson, an old lady about seventy-five, a member of the Episcopal Church, and opposed to Freedom. As far as he was concerned, however, he said, she had treated him well; but, knowing that the old lady would not be long here, he judged it was best to look out in time. Consequently, he availed himself of an Underground Rail Road ticket, and bade adieu to that hot-bed of secession, South Carolina. Indeed, he was fair enough to pass for white, and actually came the entire journey from Charleston to this city under the garb of a white gentleman. With regard to gentlemanly bearing, however, he was all right in this particular. Nevertheless, as he had been a slave all his days, he found that it required no small amount of nerve to succeed in running the gauntlet with slave-holders and slave-catchers for so long a journey.

The following pointed epistle, from Jeremiah Colburn alias William Cooper, beautifully illustrates the effects of Freedom on many a passenger who received hospitalities at the Philadelphia depot—

SYRACUSE, June 9th, 1858.

MR. STILL:—Dear Sir:—One of your Underground R.R. Passenger Drop you these few Lines to let you see that he have not forgoten you one who have Done so much for him well sir I am still in Syracuse, well in regard to what I am Doing for a Living I no you would like to hear, I am in the Painting Business, and have as much at that as I can do, and enough to Last me all the Summer, I had a knolledge of Painting Before I Left the South, the Hotell where I was working Last winter the Proprietor fail & shot up in the Spring and I Loose evry thing that I was working for all Last winter. I have Ritten a Letter to my Friend P. Christianson some time a goo & have never Received an Answer, I hope this wont Be the case with this one, I have an idea sir, next winter iff I can this summer make Enough to Pay Expenses, to goo to that school at McGrowville & spend my winter their. I am going sir to try to Prepair myself for a Lectuer, I am going sir By the Help of god to try and Do something for the Caus to help my Poor Breathern that are suffering under the yoke. Do give my Respect to Mrs Stills & Perticular to Miss Julia Kelly, I supose she is still with you yet, I am in great hast you must excuse my short letter. I hope these few Lines may fine you as they Leave me quite well. It will afford me much Pleasure to hear from you.

yours Truly,

WILLIAM COOPER.

John Thompson is still here and Doing well.

It will be seen that this young Charlestonian had rather exalted notions in his head. He was contemplating going to McGrawville College, for the purpose of preparing himself for the lecturing field. Was it not rather strange that he did not want to return to his “kind-hearted old mistress?”

THOMAS HENRY, NATHAN COLLINS AND HIS WIFE MARY ELLEN.—Thomas is about twenty-six, quite dark, rather of a raw-boned make, indicating that times with him had been other than smooth. A certain Josiah Wilson owned Thomas. He was a cross, rugged man, allowing not half enough to eat, and worked his slaves late and early. Especially within the last two or three months previous to the escape, he had been intensely savage, in consequence of having lost, not long before, two of his servants. Ever since that misfortune, he had frequently talked of “putting the rest in his pocket.” This distressing threat made the rest love him none the more; but, to make assurances doubly sure, after giving them their supper every evening, which consisted of delicious “skimmed milk, corn cake and a herring each,” he would very carefully send them up in the loft over the kitchen, and there “lock them up,” to remain until called the next morning at three or four o’clock to go to work again. Destitute of money, clothing, and a knowledge of the way, situated as they were they concluded to make an effort for Canada.

NATHAN was also a fellow-servant with Thomas, and of course owned by Wilson. Nathan’s wife, however, was owned by Wilson’s son, Abram. Nathan was about twenty-five years of age, not very dark. He had a remarkably large head on his shoulders and was the picture of determination, and apparently was exactly the kind of a subject that might be desirable in the British possessions, in the forest or on the farm.

His wife, Mary Ellen, is a brown-skinned, country-looking young woman, about twenty years of age. In escaping, they had to break jail, in the dead of night, while all were asleep in the big house; and thus they succeeded. What Mr. Wilson did, said or thought about these “shiftless” creatures we are not prepared to say; we may, notwithstanding, reasonably infer that the Underground has come in for a liberal share of his indignation and wrath. The above travelers came from near New Market, Md. The few rags they were clad in were not really worth the price that a woman would ask for washing them, yet they brought with them about all they had. Thus they had to be newly rigged at the expense of the Vigilance Committee.

The Cambridge Democrat, of Nov. 4, 1857, from which the advertisements were cut, said—

“At a meeting of the people of this county, held in Cambridge, on the 2d of November, to take into consideration the better protection of the interests of the slave-owners; among other things that were done, it was resolved to enforce the various acts of Assembly * * * * relating to servants and slaves.

“The act of 1715, chap. 44, sec. 2, provides ‘that from and after the publication thereof no servant or servants whatsoever, within this province, whether by indenture or by the custom of the counties, or hired for wages shall travel by land or water ten miles from the house of his, her or their master, mistress or dame, without a note under their hands, or under the hands of his, her or their overseer, if any be, under the penalty of being taken for a runaway, and to suffer such penalties as hereafter provided against runaways.’ The Act of 1806, chap. 81, sec. 5, provides, ‘That any person taking up such runaway, shall have and receive $6,’ to be paid by the master or owner. It was also determined to have put in force the act of 1825, chap. 161, and the act of 1839, chap. 320, relative to idle, vagabond, free negroes, providing for their sale or banishment from the State. All persons interested, are hereby notified that the aforesaid laws, in particular, will be enforced, and all officers failing to enforce them will be presented to the Grand Jury, and those who desire to avoid the penalties of the aforesaid statutes are requested to conform to these provisions.”

As to the modus operandi by which so many men, women and children were delivered and safely forwarded to Canada, despite slave-hunters and the fugitive slave law, the subjoined letters, from different agents and depots, will throw important light on the question.

Men and women aided in this cause who were influenced by no oath of secresy, who received not a farthing for their labors, who believed that God had put it into the hearts of all mankind to love liberty, and had commanded men to “feel for those in bonds as bound with them,” “to break every yoke and let the oppressed go free.” But here are the letters, bearing at least on some of the travelers:

WILMINGTON, 10th Mo. 31st, 1857.

ESTEEMED FRIEND WILLIAM STILL:—I write to inform thee that we have either 17 or 27, I am not certain which, of that large Gang of God’s poor, and I hope they are safe. The man who has them in charge informed me there were 27 safe and one boy lost during last night, about 14 years of age, without shoes; we have felt some anxiety about him, for fear he may be taken up and betray the rest. I have since been informed there are but 17 so that I cannot at present tell which is correct. I have several looking out for the lad; they will be kept from Phila. for the present. My principal object in writing thee at this time is to inform thee of what one of our constables told me this morning; he told me that a colored man in Phila. who professed to be a great friend of the colored people was a traitor; that he had been written to by an Abolitionist in Baltimore, to keep a look out for those slaves that left Cambridge this night week, told him they would be likely to pass through Wilmington on 6th day or 7th day night, and the colored man in Phila. had written to the master of part of them telling him the above, and the master arrived here yesterday in consequence of the information, and told one of our constables the above; the man told the name of the Baltimore writer, which he had forgotten, but declined telling the name of the colored man in Phila. I hope you will be able to find out who he is, and should I be able to learn the name of the Baltimore friend, I will put him on his Guard, respecting his Phila. correspondents. As ever thy friend, and the friend of Humanity, without regard to color or clime.

THOS. GARRETT.

How much truth there was in the “constable’s” story to the effect, “that a colored man in Philadelphia, who professed to be a great friend of the colored people, was a traitor, etc.,” the Committee never learned. As a general thing, colored people were true to the fugitive slave; but now and then some unprincipled individuals, under various pretenses, would cause us great anxiety.

LETTER FROM JOHN AUGUSTA.

NORRISTOWN Oct 18th 1857 2 o’clock PM

DEAR SIR:—There is Six men and women and Five children making Eleven Persons. If you are willing to Receve them write to me imediately and I will bring them to your To morrow Evening I would not Have wrote this But the Times are so much worse Financialy that I thought It best to hear From you Before I Brought such a Crowd Down Pleas Answer this and

Oblige

JOHN AUGUSTA.

This document has somewhat of a military appearance about it. It is short and to the point. Friend Augusta was well known in Norristown as a first-rate hair-dresser and a prompt and trustworthy Underground Rail Road agent. Of course a speedy answer was returned to his note, and he was instructed to bring the eleven passengers on to the Committee in Brotherly Love.

LETTER FROM MISS G. LEWIS ABOUT A PORTION OF THE SAME “MEMORABLE TWENTY-EIGHT.”

SUNNYSIDE, Nov. 6th, 1857.

DEAR FRIEND:—Eight more of the large company reached our place last night, direct from Ercildown. The eight constitute one family of them, the husband and wife with four children under eight years of age, wish tickets for Elmira. Three sons, nearly grown, will be forwarded to Phila., probably by the train which passes Phoenixville at seven o’clock of to-morrow evening the seventh. It would be safest to meet them there. We shall send them to Elijah with the request for them to be sent there. And I presume they will be. If they should not arrive you may suppose it did not suit Elijah to send them.

We will send the money for the tickets by C.C. Burleigh, who will be in Phila. on second day morning. If you please, you will forward the tickets by to-morrow’s mail as we do not have a mail again till third day.

Yours hastily,

Q. LEWIS.

Please give directions for forwarding to Elmira and name the price of tickets.

At first Miss Lewis thought of forwarding only a part of her fugitive guests to the Committee in Philadelphia, but on further consideration, all were safely sent along in due time, and the Committee took great pains to have them made as comfortable as possible, as the cases of these mothers and children especially called forth the deepest sympathy.

In this connection it seems but fitting to allude to Captain Lee’s sufferings on account of his having brought away in a skiff, by sea, a party of four, alluded to in the beginning of this single month’s report.

Unfortunately he was suspected, arrested, tried, convicted, and torn from his wife and two little children, and sent to the Richmond Penitentiary for twenty-five years. Before being sent away from Portsmouth, Va., where he was tried, for ten days in succession in the prison five lashes a day were laid heavily on his bare back. The further sufferings of poor Lee and his heart-broken wife, and his little daughter and son, are too painful for minute recital. In this city the friends of Freedom did all in their power to comfort Mrs. Lee, and administered aid to her and her children; but she broke down under her mournful fate, and went to that bourne from whence no traveler ever returns.

Captain Lee suffered untold misery in prison, until he, also, not a great while before the Union forces took possession of Richmond, sank beneath the severity of his treatment, and went likewise to the grave. The two children for a long time were under the care of Mr. Wm. Ingram of Philadelphia, who voluntarily, from pure benevolence, proved himself to be a father and a friend to them. To their poor mother also he had been a true friend.

The way in which Captain Lee came to be convicted, if the Committee were correctly informed and they think they were, was substantially in this wise: In the darkness of the night, four men, two of them constables, one of the other two, the owner of one of the slaves who had been aided away by Lee, seized the wife of one of the fugitives and took her to the woods, where the fiends stripped every particle of clothing from her person, tied her to a tree, and armed with knives, cowhides and a shovel, swore vengeance against her, declaring they would kill her if she did not testify against Lee. At first she refused to reveal the secret; indeed she knew but little to reveal; but her savage tormentors beat her almost to death. Under this barbarous infliction she was constrained to implicate Captain Lee, which was about all the evidence the prosecution had against him. And in reality her evidence, for two reasons, should not have weighed a straw, as it was contrary to the laws of the State of Virginia, to admit the testimony of colored persons against white; then again for the reason that this testimony was obtained wholly by brute force.

But in this instance, this woman on whom the murderous attack had been made, was brought into court on Lee’s trial and was bid to simply make her statement with regard to Lee’s connection with the escape of her husband. This she did of course. And in the eyes of this chivalric court, this procedure “was all right.” But thank God the events since those dark and dreadful days, afford abundant proof that the All-seeing Eye was not asleep to the daily sufferings of the poor bondman.

- A paw is a weapon with iron prongs, four inches long, to be grasped with the hand and used in close encounter. ↵