Module 9: Interactive Fiction/Twine Workshop

9.3 Introduction to Interactive Storytelling

As a brief introduction to Twine and interactive fiction, we invite you to spend a few minutes playing the two Twine games provided:

- Zoë Quinn is an American video game developer. Her 2013 game, Depression Quest, is a choose-your-own-adventure game about living with depression. Quinn’s thoughtful game illustrates the possibilities of using Twine as a medium for artistic, political, and self-expression, and explores empathy role play and the limits of choice. http://www.depressionquest.com/

- Nonbinary: A Choose-Your-Own-Adventure is a game published by Adan Jerreat-Poole (2019) about being a nonbinary video game scholar. This game explores justice and inclusion in academia and gaming communities. http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/nonbinary-twine.html

Please note that the transcript of this game is available here: http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/nonbinary-text/

After playing one or both games, take a few minutes to jot down your thoughts on the experience. Let the following questions guide your analysis:

- What choices were available to you? What choices do you wish had been available?

- How was the story told?

- What kinds of access were provided? In what ways were the games inaccessible?

- What story was being told and how did you participate in its creation?

- What emotions did the game evoke?

Interactivity and Choice

In Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals, Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman (2003) explain the impact of making choices in a game. Salen and Zimmerman argue that meaningful play requires meaningful choices that impact the narrative (p. 64). This argument is something that is often echoed in game scholarship – that the active role players have, through decision making and the direct impact these choices can have on narrative, is crucial to the meaningfulness of play.

In her book How Games Move Us: Emotion by Design, Katherine Isbister (2016) frames meaningful play as emotional responses from players, writing,

“Actions with consequences – interesting choices – unlock a new set of emotional possibilities for game designers. Ultimately, these possibilities exist because our feelings in everyday life, as well as games, are integrally tied to our goals, our decisions, and their consequences.” (p. 2)

Isbister argues that making choices allows players to experience unique emotional responses in games, such as responsibility and guilt (both emotions we may not immediately think of when we think about playing videogames). Essentially, choice is how games carry their meaning.

Before moving on, think about your experience playing either Depression Quest or Nonbinary: A Choose-Your-Own-Adventure.

- What choices in the games led to the most meaningful emotional impact for you?

- Were they choices that felt like they had consequences to them?

- And were the emotions created by these choices ones you would normally associate with videogame play?

Feel free to write your reflections in the text box below:

Limited Choices

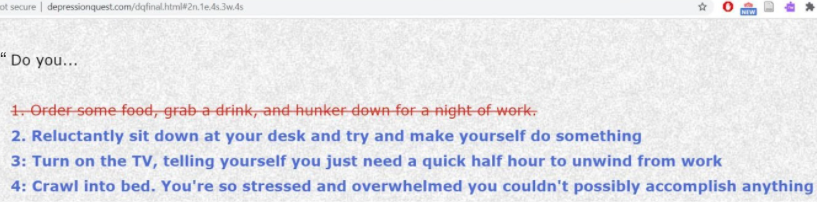

We just learned about how creating in-game choices for players that affect the game’s narrative opens a space for meaningful play and evokes powerful emotions. However, there is also value in limiting choices. In Depression Quest, for example, players lack choice in their decisions; this limited playstyle allows players to ‘play’ the experience of living with depression as conveyed by Zoë Quinn. An example of this limited choice from the game is in Figure 1 below:

In this example, Quinn takes a choice away to cleverly evoke emotion in the player. In thinking about representation and disability, this playstyle also serves to educate and perhaps challenge preconceptions players may have about depression.

Engaging Players with Interactivity

Interactivity as a whole is what creates space for meaningful engagement with narratives and games, whether this interactivity is through agency afforded to players with choices or by the lack of choice. This interactivity and engagement with a narrative can be especially affecting because, as touched upon in previous modules, digital worlds are not separate or closed off from our lived experiences in the real or physical world. Players carry their beliefs, their experiences, and their values into game worlds. Through choice (or lack thereof) and interaction with narratives, game designers can directly engage with these values, experiences, and beliefs to challenge them or reaffirm them.

Key Takeaway

Whose Choices?

It is crucial to keep in mind that choices in games are designed and framed by game creators, meaning these choices and emotions, as well as the narratives that house them, can reflect the values of those creators. In the first assigned reading for this module, Kara Stone (2019) asks,

“What if we made games that activated melancholy, or self-reflection, or tenderness? […] I think games are emotionally powerful, and it’s time we start channeling that power into a wider emotional landscape. We need to make reparative games, games that can help us heal.”

(n.p.)

Stone builds upon the idea that game designers can create unique and emotionally charged experiences through choice and interactivity, but calls into question the emotions designers choose to create. For example, in the maker spotlight for this week, Kaitlin Tremblay reflects on how

“some people have very specific ideas of what games should be or who should make games, and these people don’t always want to accommodate outside of their understanding of that.”

Kaitlin says using horror and “productive discomfort” is a way she communicates her experiences of trauma and mental illness to players.

Remember how we discussed the importance of having disabled game creators. If the games we play are not rooted in disability experience, then the choices in those games, and subsequent emotional responses, cannot properly address the “wider emotional landscape” of human experience that Stone discusses. It is within these choices that disabled game creators have some of the most powerful tools to challenge ableism and educate players.